don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Holy Family of Nazareth (year A)

Feast of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph (Year A) [28 December 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us! Here is a commentary on this Sunday's readings with a wish for every family that they may see themselves reflected in the real daily life of Nazareth, which the Bible shows us to have been truly tested by many difficulties and problems, just like any other family.

*First Reading from the Book of Sirach (3:2-6, 12-14)

Ben Sira insists on the respect due to parents because, in the 2nd century BC (around 180), family authority was weakening. In Jerusalem, under Greek rule, despite religious freedom, new mentalities were slowly spreading: contact with the pagan world threatened to change the way Jews thought and lived. For this reason, Ben Sira, teacher of Wisdom, defends the foundations of faith starting from the family, the primary place of transmission of faith, values and religious practices. The text is therefore a strong appeal in favour of the family and is also a profound meditation on the fourth commandment: 'Honour your father and your mother', formulated in Exodus as a promise of long life and in Deuteronomy also of happiness. About fifty years later, Ben Sira's grandson, translating the work into Greek, adds a decisive motivation: parents are instruments of God because they give life; for this reason, they deserve honour, remembrance and gratitude. This commandment also responds to human common sense: a balanced society is born of solid families, while their breakdown generates serious psychological and social consequences. However, at the deepest level, family harmony belongs to God's own plan. Some of Ben Sira's expressions seem to suggest a 'calculation' ('whoever honours his father obtains forgiveness of sins...'), but in reality it is not a mechanical reward: God's Law is always a path to grace and happiness. As Deuteronomy teaches, the commandments are given for the good and freedom of man. When Ben Sira states that honouring one's parents obtains forgiveness, we see a progress in revelation: true reconciliation with God comes through reconciliation with one's neighbour, in harmony with the prophets ("I desire mercy, not sacrifice"). Being respectful children to our parents means being faithful children to God as well. It is no coincidence that, among the Ten Commandments, only two are formulated in positive terms: the Sabbath and honouring our parents. They find their fulfilment in the great commandment of love of neighbour, which begins precisely with our parents, our first 'neighbours'. This is why Ben Sira's text is particularly appropriate during the festive season, when family ties are strengthened or rediscovered.

*Most important elements: +Historical context: 2nd century BC, Hellenistic influence. +Family as the primary place of transmission of faith. +Defence of the fourth commandment. +Parents as instruments of God in the gift of life. +God's law as the way to happiness, not calculation. +Reconciliation with God through one's neighbour. +Honouring one's parents as the first act of love for one's neighbour.

*Responsorial Psalm (127/128)

This psalm is called the 'Song of Ascents' because it was intended to be sung during the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, probably in the final moments, climbing the steps of the Temple. The text seems to be structured like a liturgical celebration: at the entrance to the Temple, the priests welcome the pilgrims and offer a final catechesis, proclaiming the blessedness of the man who fears the Lord and walks in his ways. The blessing concerns work, family, fertility and domestic peace: the fruit of one's hands, one's wife as a fruitful vine, one's children as olive shoots around the table. The assembly of pilgrims responds by confirming that those who fear the Lord are blessed. This is followed by the solemn formula of priestly blessing: from Mount Zion, the Lord grants his blessing, allowing us to contemplate the good of Jerusalem and the continuity of generations throughout our lives. The emphasis on work, prosperity and happiness may seem too 'earthly', but the Bible strongly affirms that God created man for happiness. The human desire for success and family harmony coincides with God's plan; this is why Scripture often speaks of 'happiness' and 'blessing', without irony, even in the face of the sufferings of history. The biblical term 'happy' does not indicate an automatic guarantee of success, but the true good, which is closeness to God. It is both recognition and encouragement. André Chouraqui translates 'happy, blessed' as 'on the way', to say: you are on the right path, continue. Israel quickly understood that God accompanies his people in their desire for happiness and opens up a path of hope before them (cf. Jer 29:11). The entire Bible affirms God's merciful plan for humanity, as St Paul reminds us in his letter to the Ephesians. Biblical happiness therefore has two dimensions: it is first and foremost God's plan, but it is also a choice made by human beings. The path is clear and straight: fidelity to the Law, which is summed up in love of God and humanity. Jesus walked this path to the end and invites his disciples to follow him, promising true blessedness to those who put his word into practice. What remains is the seemingly paradoxical expression: "Blessed are those who fear the Lord." This is not about fear, but reverent awe. Chouraqui renders it as: 'on the way, you who would tremble before God'. It is the emotion of those who feel small before a great love. Having discovered that God is love, Israel no longer fears as a slave, but as a child before the strength and tenderness of the father. It is no coincidence that Scripture uses the same verb for the respect due to God and to parents (Lev 19:3). Faith is therefore the certainty that God wants what is good for man; for this reason, "fearing the Lord" is equivalent to "walking in his ways". When Jerusalem lives this fidelity, it will fulfil its vocation as a city of peace; the psalm anticipates this by proclaiming: "May you see the good of Jerusalem all the days of your life".

*Most important elements: +The psalm, as a Song of Ascents and pilgrimage song, has a liturgical structure: priests, assembly, blessing. +Blessing on work, family and fertility. +God creates man for happiness and "blessed" are those who are close to God, and Chouraqui translates "blessed" = on the way. +God's benevolent plan for humanity, which sees happiness as a gift from God and a choice of man. +Jesus as the fulfilment of the journey of love. +'Fear of God' as a filial attitude, not fear. +Jerusalem called to be a city of peace.

*Second Reading from St Paul's Letter to the Colossians (3:12-21)

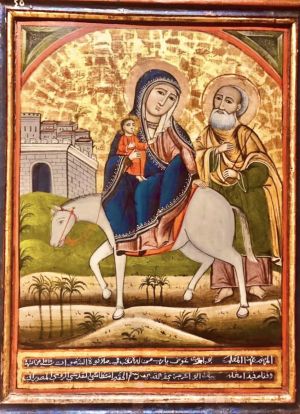

Today's liturgy invites us to contemplate the Holy Family: Joseph, Mary and Jesus. It is a simple family, and it is called "holy" because God himself is at its centre. However, it is not an idealised or unreal family: the Gospels clearly show that it went through real trials and difficulties. Joseph is troubled by Mary's mysterious pregnancy, Jesus is born in poor conditions, the family experiences exile in Egypt and later the anguish of Jesus being lost and found in the Temple, without fully understanding the meaning of it all. Precisely for this reason, the Holy Family appears as a real family, marked by struggles and questions similar to those of any other family. This reality reassures us and gives meaning to St Paul's recommendations in his letter to the Colossians, where he calls for patience and forgiveness, virtues that are necessary in daily life. Colossae, a city in present-day Turkey, was not visited directly by Paul: the Christian community was founded thanks to Epaphras, his disciple. Paul writes from prison, concerned about certain deviations that threaten the purity of the Christian faith. The tone of the letter alternates between contemplative enthusiasm for God's plan and very strong warnings against misleading doctrines. At the centre of his message is always Jesus Christ, the heart of history and of the world. Paul invites Christians to model their lives on Him: to clothe themselves with tenderness, goodness, peace and gratitude, doing everything in the name of the Lord Jesus. The baptised, in fact, form the Body of Christ. Taking up and deepening an image already used with the Corinthians, Paul affirms that Christ is the head and believers are the members, called to support one another in building up the edifice of the Church. The text also addresses family relationships, with expressions that may be difficult, such as the invitation to wives to submit. In the biblical context, however, this submission is not equivalent to servitude, but is part of a vision based on love and responsibility. Paul, after referring to language common at the time, addresses an even stronger requirement to husbands: to love their wives with respect and without harshness. Christian obedience arises from trust in God's love and is expressed in relationships marked by tenderness, respect and mutual giving.

*Important elements: +The Holy Family as a real family, not idealised, with the concrete trials experienced by Joseph, Mary and Jesus, and an invitation to patience and forgiveness in family life. +Context of the letter to the Colossians and the role of Epaphras with Paul's concern for the fidelity of the Christian faith. +Centrality of Jesus Christ in the lives of believers as the Body of Christ, called to support one another. +Family relationships based on love and respect where biblical submission is understood as trust and gift, not slavery. +Christian obedience rooted in the certainty that God is Love.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (2:13-15, 19-239

The episode of the Holy Family's flight to Egypt deliberately recalls another great biblical story: that of Moses and the people of Israel, twelve centuries earlier, enslaved in Egypt. Just as the pharaoh ordered the killing of male newborns and Moses was saved to become the liberator of his people, so Jesus escapes Herod's massacre and becomes the saviour of humanity. Matthew invites us to recognise in Jesus the new Moses, the fulfilment of the promise of Deuteronomy 18:18: a prophet raised up by God like Moses himself. A second sign of the fulfilment of the Scriptures is the quotation from Hosea 11:1: "Out of Egypt I called my son." Originally referring to the people of Israel, Matthew applies it to Jesus, presenting him as the New Israel, the one who fully realises the Covenant. The title Son of God, already attributed to kings and the Messiah, acquires its full meaning in Jesus: in the light of the resurrection and the gift of the Spirit, believers recognise that Jesus is truly the Son of God, God from God, as the Christian faith confesses. A third sign is the statement: "He will be called a Nazarene". Although the Old Testament does not mention Nazareth, Matthew plays on linguistic and symbolic resonances: netser (messianic 'shoot' of the line of David), nazir (consecrated to God), and natsar ('to guard'). Nazareth thus becomes the sign of God's choice of the humble and insignificant. Furthermore, when Christians are despised as 'Nazarenes', Matthew encourages them by reminding them that Jesus also bore that title: what appears despicable to men is precious in the eyes of God. In the story, Matthew constructs two parallel scenes: the flight into Egypt and the return from Egypt. In both there is a historical context, the appearance of the angel to Joseph in a dream, immediate obedience and the conclusion: thus was fulfilled "what had been said through the prophets". The parallelism relates the titles Son of God and Nazarene, showing an unexpected Messiah: glorious and humble at the same time. This is why the text is proclaimed on the feast of the Holy Family: Jesus is the Son of God, but he grows up in a simple family and in an insignificant village. It is the great Christian paradox: divine history is fulfilled in the most ordinary everyday life of human families. Ancient commentators such as Pseudo-Dionysius and Pseudo-Chrysostom reflect on the flight into Egypt, not only as a historical fact but as a manifestation of the plan of salvation: Christ, though he is God, submits himself to the law of the flesh and to divine guidance, demonstrating the true humanity and obedience of the Messiah. St Jerome, on the other hand, emphasises that not only Herod, but also the high priests and scribes sought the Lord's death from the very first moments of his coming into the world, showing the spiritual hostility that Jesus would encounter throughout his mission. Another interpretation by some ancient Fathers sees in the stay in Egypt a salvific dimension not only for Jesus himself, but symbolically for the world: He goes to that land historically associated with oppression and paganism not to stay, but to bring light and salvation, confirming that the coming of Christ is for everyone, even for peoples far from God. Thus, for the ancient commentators, the story is not mere narration: it is a theological revelation of the mystery of Christ, who enters human history as free obedience for our salvation and the fulfilment of prophetic promises.

*St. Irenaeus of Lyons (Against Heresies) writes: "Jesus is the recapitulation of all history: what was lost in Adam is found again in Christ." This is often applied by the Fathers to the flight into Egypt: Christ retraces the history of Israel to bring it to fulfilment.

*Important elements: +Parallelism between Jesus and Moses, Jesus as the new Moses and the new Israel. +Fulfillment of the Scriptures according to Matthew: 'Out of Egypt I called my son' (Hos 11:1). +Title of Son of God in the full Christological sense. +Symbolic meaning of Nazareth / Nazarene. +Divine choice of the humble and despised, and unexpected Messiah: divine glory and concrete humility. +Parallel narrative structure: flight and return from Egypt. +Holy Family: the divine experienced in everyday life

+Giovanni D'Ercole

Holy Family of Nazareth (year A)

(Mt 2:13-15, 19-23)

Matthew 2:13 As soon as they had left, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, "Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you, for Herod is seeking the child to kill him."

Matthew 2:14 Joseph woke up, took the child and his mother during the night, and fled to Egypt,

Matthew 2:15 where he remained until the death of Herod, so that what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet might be fulfilled:

"Out of Egypt I called my son."

First, let us understand how power works: it does not want to pay homage to the newborn King, but wants to kill him. He is the Rival, the one who can take away his power and throne. Power, in order to eliminate the Rival, in order to maintain its dominion, is ready to sacrifice the lives of its subjects. It is something aberrant; power should have the task of defending the lives of its subjects, but Herod applies his strategy without scruples and kills all the children in order to retain power.

An angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. There are many dreams that accompany Jesus' childhood: they indicate divine initiative and providence that thwart Herod's plans. The angel's announcement tells us of God's intervention in history. We note how these dreams are given to Joseph and not to Mary. Joseph is responsible before God and men for the Mother and Child.

The Lord addresses him in the dream and gives him a peremptory order to be carried out immediately: "Get up, take the child and his mother and flee to Egypt, and stay there until I tell you." Joseph is guided in every detail. He must go to Egypt and stay there until the Lord again tells him that he can return. For salvation to be accomplished, it is necessary that the order be carried out to the letter. The Lord is perfect in his ways. If man responds to the Lord's perfection with obedience, salvation is accomplished. All the evils of the world arise when the foolishness of creatures, who dare to think they are wiser than they are, is introduced into God's perfection.

In this circumstance, Egypt is a place of protection. At that time, the Holy Family could easily find a place to live among the many Jewish colonies, the largest of which was in Alexandria. But Egypt is also the place where the history of Israel as God's people began. The child Jesus will have to leave Egypt to enter his land. Matthew thus theologically re-presents the exodus that Jesus, the liberating Messiah, will accomplish, leading the people to a new land of freedom, to true liberation. They left 'at night' (v. 14). This is a reminder of the liberation that the people of Israel experienced on Passover night, described in the book of Exodus. Just as the people fled from the threat of Pharaoh, so now Joseph brings Jesus to safety from the threat of Herod.

However, salvation always comes at a cost in suffering, sacrifice and pain. Without wanting to apologise for pain, pain serves to give a person ever greater holiness. Pain and suffering are the crucible that purifies our spirit of all encrustations and brings us closer to the holiness of God.

Without sacrifice, there is no true obedience, because true obedience always generates a purifying sacrifice of life. It is the living, holy sacrifice pleasing to God of which the Apostle Paul speaks. The evil of today's world lies precisely in Satan's desire to abolish all self-denial and renunciation from our lives. We want everything, right now, immediately. They want to indulge the body in every vice, the soul in every sin, and the spirit in every evil thought. They want to live in a world without sacrifice, without suffering (which is why euthanasia and the killing of those considered a dead weight on society will become increasingly common).

People want to live in a world without any deprivation. Once upon a time, people were born and died at home, and the family shared in the greatest joy and the greatest sadness, but at least the sick person died with the comfort of their loved ones. People want to live in a world that hides the mystery of death and pain by removing it from their homes, ignoring the fact that the very sight of pain is a powerful moment of openness to faith.

Joseph and his family remained in Egypt until after Herod's death. Matthew says that this happened in fulfilment of the prophecy of Hosea 11:1 - 'Out of Egypt I called my son' - which speaks of something else entirely, namely the historical experience of the nation of Israel: the exodus from Egypt. What does this have to do with the Messiah? The evangelist creates a sort of parallel link between the events of ancient Israel and those of Jesus, as if to say that in Jesus, in some way, the whole history of the people of Israel converges, relived by him in obedience and full submission to the Father. In other words, in the analogous experience of Israel, the son of God, and the Messiah, the son of God, both in Egypt out of necessity and both freed by divine providence, Matthew sees Jesus recapitulating the history of Israel, whose experience he relives in his own person.

Indeed, Jesus recapitulates in himself and brings to fulfilment the whole history of salvation. Just as the exodus from Egypt was the dawn of redemption, so the childhood of Jesus is the dawn of the messianic age, and Matthew demonstrates the fulfilment of the Scriptures in Jesus. It will be from him that a new Israel will emerge, regenerated by the Spirit.

Everything that came before Christ is only an image of what the Lord would accomplish through Jesus Christ. The events of the people of Israel were a preparation for the coming of the Messiah, who represents the point of convergence of all Scripture. The true Son of God is Jesus Christ. Israel is only a sign of what the Lord was about to do for the salvation of humanity. This is why Matthew applies to Jesus Christ everything in the Old Testament that referred to Israel.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

Christmas Day

Christmas Day 2025 [Midnight Mass]

May God bless you and may the Virgin Mary protect us. Best wishes for this holy Christmas Day of Christ. I offer for your consideration a commentary on the biblical texts of the midnight and daytime Masses.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (9:1-6)

To understand Isaiah's message in this text, one must read this verse, the last of chapter 8, which directly precedes it: 'God humbled the land of Zebulun and Naphtali in the past, but in the future he will glorify the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the nations' (v. 23). The text does not allow us to establish the date of its writing with precision, but we know two things with certainty: the political situation to which it refers, even if the text may have been written later. And we also know the meaning of the prophetic word, which seeks to revive the hope of the people. At the time evoked, the people were divided into two kingdoms: in the north, Israel, with its capital at Samaria, politically unstable; in the south, the kingdom of Judah, with its capital at Jerusalem, the legitimate heir to the Davidic dynasty. Isaiah preached in the South, but the places mentioned (Zebulun, Naphtali, Galilee, the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan) belong to the North. These areas – Galilee, the way of the sea, Transjordan – suffered a particular fate between 732 and 721 BC. In 732, the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III annexed these regions. In 721, the entire northern kingdom fell. Hence the image of 'the people walking in darkness', perhaps referring to the columns of deportees. To this defeated people, Isaiah announces a radical reversal: God will bring forth a light in the very regions that have been humiliated. Why do these promises also concern the South? Jerusalem is not indifferent to what is happening in the North: because the Assyrian threat also hangs over it; because the schism is experienced as a wound and there is hope for the reunification of the people under the house of David. The advent of a new king, the words of Isaiah ("A great light has risen...") belonged to the ritual of the sacred royal: every new king was compared to a dawn that brings hope for peace and unity. Isaiah therefore announces: the birth of a king ("A child is born for us..."), called "Prince of Peace", destined to restore strength to the Davidic dynasty and reunite the people. This certainty comes from faith in the faithful God, who cannot betray his promises. The prophecy invites us not to forget God's works: Moses reminded us, 'Be careful not to forget'. Isaiah said to Ahaz, 'Unless you believe, you will not be established' (Isaiah 7:9). The promised victory will be "like the day of Midian" (Judges 7): God's victory achieved through a small faithful remnant with Gideon. The central message is "Do not be afraid: God will not abandon the house of David." Today we could say: Do not be afraid, little flock, God does not abandon his plan of love for humanity, and light is believed in the night. Historical context: When Isaiah announces these promises, King Ahaz has just sacrificed his son to idols out of fear of war, undermining the very lineage of David. But God, faithful to his promises, announces a new heir who will restore the line of David: hope is not cancelled out by human sin.

Most important elements. +The context: Assyrian annexations (732–721 BC) devastating the northern regions. +Isaiah's words are a prophecy of hope for a people in darkness.

+The announcement is linked to the sacred royal line: the birth of a new Davidic king. +The promise concerns unity, peace and God's faithfulness to his covenant with David. +Victory will be God's work, like Gideon's victory. +Even Ahaz's sin does not nullify God's plan: God remains faithful.

*Responsorial Psalm (95/96)

The liturgy offers only a few verses from Psalm 95/96, but the entire psalm is filled with a thrill of joy and exultation. Yet it was composed in a historical period that was not at all exciting: what vibrates is not human enthusiasm, but the faith that hopes, that hope that anticipates what is not yet possessed. The psalm projects us to the end of time, to the blessed day when all peoples will recognise the Lord as the one God and place their trust in him. The image is grandiose: we are in the Temple of Jerusalem. The esplanade is filled with an endless multitude of people, gathered 'from the ends of the earth'. Everyone sings in unison: 'The Lord reigns!' It is no longer Israel's acclamation for an earthly king, but the cry of all humanity recognising the King of the world. And it is not only humanity that acclaims: the earth trembles, the seas roar, the countryside and even the trees of the forests dance. The whole of creation recognises its Creator, while man has often taken centuries to do so. The psalm also contains a criticism of idolatry: 'the gods of the nations are nothing'. Over the centuries, the prophets have fought the temptation to rely on false gods and false securities. The psalm reminds us that only the Lord is the true God, the One who 'made the heavens'. The reason why all peoples now flock to Jerusalem is that the good news has finally reached the whole world. And this was possible because Israel proclaimed it every day, recounting the works of God: the liberation from Egypt, the daily liberations from many forms of slavery, the most serious danger: believing in false values that do not save. Israel has received the immense privilege of knowing the one God, as the Shema proclaims: "The Lord is one."

But it has received this privilege in order to proclaim it: "You have been given to see, so that you may know... and make it known." Thanks to this proclamation, the good news has reached "the ends of the earth" and all peoples gather in the "house of the Father." . The psalm anticipates this final scene and, while waiting for it to come true, Israel sings it to renew its faith, revive its hope and find the strength to continue the mission entrusted to it.

Most important elements: +Psalm 95/96 is a song of eschatological hope: it anticipates the day when all humanity will recognise God. +The story describes a cosmic liturgy: humanity and creation together acclaim the Lord. +Strong denunciation of idolatry: the 'gods of the nations' are nothing. +Israel has the task of proclaiming God's works and his deliverance every day. +Its vocation: to know the one God and make him known. +The psalm is sung as an anticipation of the future, to keep the faith and mission of the people alive.

*Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul to Titus (2:11-14) and for the Dawn Mass (3:4-7)

Through Baptism, we are immersed in God's grace. The Cretans had a bad reputation even before St Paul's time. A poet of the 6th century BC, Epimenides of Knossos, called them "liars by nature, evil beasts, lazy bellies". Paul quotes this phrase and adds: "This is true!". And it was precisely because he was well aware of this difficult humanity that Paul founded a Christian community, which he then entrusted to Titus to organise and lead. The Letter to Titus contains the founder's instructions to the leaders of the young Church of Crete. Many scholars believe that the letter was written towards the end of the first century, after Paul's death, but it respects his style and is faithful to his theology. In any case, the difficulties of the Cretans must still have been very much alive. The letter — very short, just three pages — contains concrete recommendations for all categories of the community: elders, young people, men, women, masters, slaves, and even those in charge, who are admonished to be blameless, hospitable, just, self-controlled, and far from violence, greed, and drunkenness. It is a long list of advice that gives an idea of how much work still needed to be done. The central theological passage of the letter—the one proclaimed in the liturgy—explains the foundation of all Christian morality, namely that new life is born from Baptism. Paul links moral advice to a decisive statement: "The grace of God has been revealed for the salvation of all." The message is this: Behave well, because God's grace has been revealed, and this means that moral change is not a human effort, but a consequence of the Incarnation. When Paul says 'grace has been revealed', he means that God became man and, through Baptism, immersed in Christ, we are reborn: saved through the washing of regeneration and renewal in the Holy Spirit (Titus 3:5). We are not saved by our own merits, but by mercy, and God asks us to be witnesses to this. God's plan is the transformation of the whole of humanity, gathered around Christ as one new man. This goal seems distant, and unbelievers consider it a utopia, but believers know and confess that it is promised by God, and therefore it is a certainty. For this reason, we live "in the hope of the blessed hope and the manifestation of the glory of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ." The words that the priest pronounces after the Our Father in the Mass echo this very expectation: 'while we await the fulfilment of the blessed hope...'. This is not an escape from reality, but an act of faith: Christ will have the last word on history. This certainty nourishes the entire liturgy, and the Church already lives as a humanity already gathered in Christ and reaching towards the future, so that when the end comes, it will be possible to say: "They rose up as one man, and that man was Jesus Christ."

Historical note: When was the Christian community of Crete born? Two hypotheses: During Paul's transfer to Rome (Acts 27), the ship stopped at "Good Harbours" in the south of the island. But the Acts do not mention the founding of a community, and Titus was not present. During a fourth missionary journey after Paul's release: his first imprisonment in Rome was probably "house arrest"; once freed, Paul would have evangelised Crete on this last journey.

Important points to remember: +The Cretans were considered difficult, but Paul founded a community there anyway. +The Letter to Titus contains concrete instructions for structuring the nascent Church. +Christian morality arises from the Incarnation and Baptism, not from mere human effort. +God saves through mercy and asks for witness, not merit. +God's plan: to reunite humanity in Christ as one new man. +The expectation of the 'blessed hope' is certainty and sustains liturgical life.

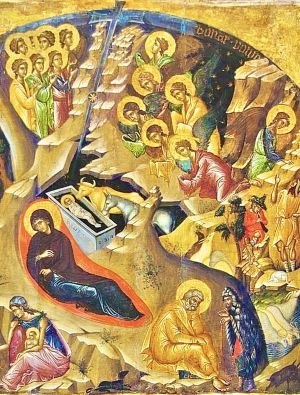

*From the Gospel according to Luke (2:1-14)

Isaiah, announcing new times to King Ahaz, speaks of the 'jealous love of the Lord' as the force capable of fulfilling the promise (Is 9:6). This conviction runs through the entire account of Jesus' birth in Luke's Gospel. The night in Bethlehem resounds with the angels' announcement: "Peace to those whom the Lord loves," which would be better said as "Peace to those whom God loves." In fact, there are no "loved and unloved people" because God loves everyone and gives his peace to all. God's entire plan is encapsulated in this phrase, which John summarises as follows: "God so loved the world that he gave his only Son" (Jn 3:16). Faced with a God who presents himself as a newborn baby, there is nothing to fear: perhaps God chose to be born in this way so that our fears of him would fall away forever. Like Isaiah in his time, the angel also announces the birth of the expected King: "Today a Saviour, Christ the Lord, is born to you in the city of David. He is the son promised in Nathan's prophecy to David (2 Sam 7): a stable lineage, a kingdom that lasts forever. This is why Luke insists on Joseph's origins: he belongs to the house of David and, for the census, he goes up to Bethlehem, a place also indicated by the prophet Micah as the homeland of the Messiah, who will be the shepherd of the people and the bringer of peace (Mic 5). The angels therefore announce "great joy" . But what is surprising is the contrast between the greatness of the Messiah's mission and the smallness , the minority of his conditions: the 'heir of all things' (Heb 1:2) is born among the poor, in the dim light of a stable; the Light of the world appears almost voluntarily hiding himself; the Word that created the world wants to learn to speak like any newborn baby. And in this light, it is not surprising that many "did not recognise him". The sign of God is not in the exceptional but in the simple and poor everyday life: it is there that the mystery of the Incarnation is revealed, and the first to recognise it are the little ones and the poor, because God, the "Merciful One", allows himself to be attracted only by our poverty. Bending down over the manger in Bethlehem, then, means learning to be like Him, because it is from this humble 'cathedra' that the almighty God communicates to us the power to become children of God (Jn 1:12).

*Final note. The firstborn, a legal term, had to be consecrated to God, and in biblical language this does not mean that other children came after Jesus, but that there were none before him. Bethlehem literally means 'house of bread'; the Bread of Life is given to the world. The titles attributed to Jesus recall those attributed to the Roman emperor venerated as 'god' and 'saviour', but the only one who can truly bear these titles is the newborn child of Bethlehem.

Key points to remember: +Isaiah and the 'jealous love of the Lord': the promise of a future king (Isaiah 9:6). +Announcement of the angels: 'Peace to men because God loves them'. +The heart of the Gospel: 'God so loved the world that he gave his only Son' (John 3:16). +The newborn child eliminates all fear of God: God chooses the way of fragility. +Fulfillment of promises +Nathan's prophecy to David (2 Sam 7). +Micah's prophecy about Bethlehem (Mic 5). +Joseph: Davidic descent. +Surprising contrast: greatness of the Messiah vs. extreme poverty of birth. +Christological titles: "Heir of all things" (Heb 1:2). "Light of the world". "Word" who becomes a child. +The sign of God is poor normality: the mystery of the Incarnation in everyday life +The poor and the little ones recognise him first. +Our vocation: to become children of God (Jn 1:12) by imitating his mercy.

St Ambrose of Milan – Brief commentary on Lk 2:1-14 “Christ is born in Bethlehem, the ‘house of bread’, so that it is understood from the beginning that He is the Bread that came down from heaven. His manger is the sign that He will be our nourishment. The angels announce peace, because where Christ is, there is true peace. And the shepherds are the first to receive the news: this means that grace is not given to the proud, but to the simple. God does not manifest himself in the palaces of the powerful, but in poverty; thus he teaches that those who want to see the glory of God must start from humility."

Christmas Day 2025 [Mass of the Day]

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (52:7-10)

The Lord comforts his people. The cry, "Break forth together into songs of joy, ruins of Jerusalem," places Isaiah's text precisely in the time of the Babylonian Exile (587 BC), when Jerusalem was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar's army. The devastated city, the deportation of the people, and the long wait for their return had led to discouragement and loss of hope. In this context, the prophet announces a decisive turning point: God has already acted. The words "Comfort, comfort my people" become a certainty that the return is imminent. Isaiah imagines two symbolic figures: the messenger, who runs to announce the good news, and the watchman, who sees the liberated people advancing from the walls of Jerusalem. In the ancient world, the messenger on foot was the only means of rapid communication, while the watchman kept vigil from the top of the walls or hills. Thus Isaiah sings of the beauty of the footsteps of those who announce peace, salvation and good news. Not only is the people saved, but the city will also be rebuilt: for this reason, even the ruins are invited to rejoice. The liberation of Israel manifests the power of God, who shows 'his holy arm'. As in the Exodus from Egypt, God intervenes forcefully to redeem his people. Isaiah uses the term 'He has redeemed Jerusalem' (Go'el): God is the closest relative who liberates, not out of self-interest, but out of love. During the exile, the people come to a fundamental discovery: the election of Israel is not an exclusive privilege, but a universal mission. God's salvation is intended for all nations, so that every people may recognise the Lord as Saviour. Re-read in the light of Christmas, this announcement finds its fulfilment: God has definitively shown his holy arm in Jesus Christ. Today, the mission of believers is that of the messenger: to announce peace, the good news, and to proclaim to the world that God reigns.

Most important elements in the text: +God (the Lord) is the true protagonist: Go'el, liberator, king who returns to Zion. + Israel, the chosen people, freed from exile, is called to a universal mission. +The messenger is the figure who announces the good news, peace and salvation. +The watchman, the one who keeps watch, recognises the signs of salvation and announces the coming of the Lord. +Jerusalem (the holy city) destroyed but destined for reconstruction; symbol of the restored people.

*Responsorial Psalm (97/98)

As always, only a few verses are proclaimed, but the commentary covers the entire psalm, whose theme is: the people of the Covenant... at the service of the Covenant of peoples. All the ends of the earth have seen the victory of our God': it is the people of Israel who speak and say 'our God', thus affirming the unique and privileged bond that unites them to the God of the universe. However, Israel has gradually come to understand that this relationship is not an exclusive possession, but a mission: to proclaim God's love to all people and to bring the whole of humanity into the Covenant. The psalm clearly expresses what can be defined as 'the two loves of God': faithful love for his chosen people, Israel; universal love for all nations, that is, for the whole of humanity. On the one hand, it proclaims that the Lord has made known his victory and his justice to the nations; on the other hand, it recalls his faithfulness and love for the house of Israel, formulas that recall the whole history of the Covenant in the desert, when God revealed himself at Sinai as a God of love and faithfulness (Ex 19-24). The election of Israel, therefore, is not a selfish privilege, but a fraternal responsibility: to be an instrument for all peoples to enter into the Covenant. As André Chouraqui stated, the people of the Covenant are called to become instruments of the Covenant of peoples. This universal openness is also emphasised by the literary structure of the psalm, constructed according to the process of 'inclusion'. The central phrase, which speaks of God's faithfulness to Israel, is framed by two statements that concern all humanity: at the beginning, the nations; at the end, the whole earth. In this way, the text shows that the election of Israel is central, but oriented towards radiating salvation to all. During the Feast of Tabernacles in Jerusalem, Israel acclaims the Lord as king, aware that it is already doing so on behalf of all humanity, anticipating the day when God will be recognised as king of the whole earth. The psalm thus insists on a second fundamental dimension: the kingship of God. The acclamation is not a simple song, but a true cry of victory (teru‘ah), similar to that which was raised on the battlefield or on the day of a king's coronation. The theme of victory returns several times: the Lord has won with his holy arm and his mighty hand, he has manifested his justice to the nations, and the whole earth has seen his victory. This victory has a twofold meaning. On the one hand, it recalls the liberation from Egypt, God's first great act of salvation, remembered in the images of his mighty arm and the wonders performed in the crossing of the sea. On the other hand, it announces the final and eschatological victory, when God will triumph definitively over every force of evil. For this reason, the acclamation is full of confidence: unlike the kings of the earth, who disappoint, God does not disappoint. Christians, in the light of the Incarnation, can proclaim with even greater force that the King of the world has already come and that the Kingdom of God, the Kingdom of love, has already begun, even if it has yet to be fully realised.

Important elements of the text: +The privileged relationship between Israel and God, +Israel's universal mission in the service of humanity. +The "two loves of God": for Israel and for all nations. +The Covenant as God's faithfulness and love in history. +The literary structure of "inclusion". +The proclamation of God's kingship and the cry of victory (teru'ah) and liturgical language. +The memory of the liberation from Egypt and the expectation of God's final victory at the end of time. +The Christian reinterpretation in the light of the Incarnation. +The reference to musical instruments of worship. + The image of God's power, which at Christmas is manifested in the fragility of a child.

*Second Reading from the Letter to the Hebrews (1:1-6)

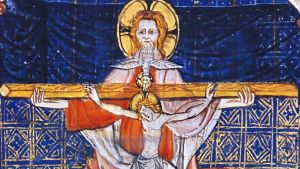

The statement "God spoke to the fathers through the prophets" shows that the Letter to the Hebrews is addressed to Jews who have become Christians. Israel has always believed that God revealed himself progressively to his people: since God is not accessible to man, it is He who takes the initiative to make himself known. This revelation takes place through a gradual process of teaching, similar to the education of a child, as Deuteronomy reminds us: God educates his people step by step. For this reason, in every age, God has raised up prophets, considered to be the 'mouth of God', who have spoken in a way that was understandable to their time. He has spoken 'many times and in many ways', forming his people in the hope of salvation. With Jesus Christ, however, we enter the time of fulfilment. The author of the Letter to the Hebrews distinguishes two great periods: the time before Christ and the time inaugurated by Christ. In Jesus, God's merciful plan of salvation finds its full fulfilment: the new world has already begun. After the resurrection, the early Christians gradually came to understand that Jesus of Nazareth was the expected Messiah, but in an unexpected form. Expectations were different: a Messiah-king, a Messiah-prophet, a Messiah-priest. The author affirms that Jesus is all of these together.

Jesus is the prophet par excellence: while the prophets were the voice of God, Jesus is the very Word of God, through whom everything was created. He is the reflection of the Father's glory and its perfect expression: whoever sees Him sees the Father. As a priest, Jesus re-establishes the Covenant between God and humanity. Living in perfect filial relationship with the Father, he accomplishes the purification of sins. His priesthood does not consist of external rites, but of a life totally given in love and obedience to the Father. Jesus is also the Messiah-King. The royal prophecies apply to him: he sits at the right hand of the divine Majesty and is called the Son of God, the royal title par excellence. His kingdom surpasses that of the kings of the earth: he is lord of all creation, superior even to the angels, who adore him. This implicitly affirms his divinity. To be Christ, therefore, means to be prophet, priest and king. This text also reveals the vocation of Christians: united with Christ, they share in his dignity. In baptism, believers are made participants in Christ's mission as prophet, priest and king. The fact that this passage is proclaimed at Christmas invites us to recognise all this depth in the child in the manger: He carries within himself the mystery of the Son, the King, the Priest and the Prophet, and we live in Him, with Him and for Him.

Most important elements of the text: +The progressive revelation of God. +The role of prophets in the history of Israel. +Jesus as the definitive fulfilment of revelation. +Christ, the Word of God and reflection of his glory. +Christ, priest who re-establishes the Covenant. +Christ, king, Son of God and Lord of creation. +The unity of the three functions: prophet, priest and king. +The participation of Christians in this mission through baptism

*From the Gospel according to John (1:1-18)

Creation is the fruit of love. 'In the beginning': John deliberately takes up the first word of Genesis ('Bereshit'). It does not indicate a mere chronological succession, but the origin and foundation of all things. "In the beginning was the Word": everything comes from the Word, the Word of love, from the dialogue between the Father and the Son. The Word is "turned towards God" (pros ton Theon), symbolising the attitude of dialogue: looking the other in the eye, opening oneself to encounter. Creation itself is the fruit of this dialogue of love between the Father and the Son, and man is created to live it. We are the fruit of God's love, called to a filial dialogue with Him. Human history, however, shows the rupture of this dialogue: the original sin of Adam and Eve represents distrust in God, which interrupts communion. Conversion, that is, 'turning around', allows us to reconcile dialogue with God. The future of humanity is to enter into dialogue. Christ lives this dialogue with the Father perfectly: He is humanity's 'Yes' to the Father. Through Him, we are reintroduced into the original dialogue, becoming children of God for those who believe in Him. Trust in God ("believing") is the opposite of sin: it means never doubting God's love and looking at the world through His eyes. The Incarnate Word (The Word became flesh) shows that God is present in concrete reality; we do not need to flee from the world to encounter Him. Like John the Baptist, we too are called to bear witness to this presence in our daily lives.

Main elements of the text: +Creation as the fruit of the dialogue of love between the Father and the Son: + In the beginning indicates origin and foundation, not just chronology. +The Word as the creative Word and the beginning of dialogue. +Man created to live in filial dialogue with God

and The breaking of dialogue in original sin. +Conversion as a 'half-turn' to reconcile the relationship with God. +Christ as perfect dialogue and humanity's 'Yes' to the Father. +Becoming children of God through faith. +The presence of God in concrete reality and in the flesh of the Word. +The call of believers to be witnesses of God's presence

Commenting on John's Prologue, St Augustine writes: 'The Word was not created; the Word was with God, and everything was made through Him. He is not merely a message, but the very Wisdom and Love of God who communicates himself to men." Augustine thus emphasises that creation and humanity are not an accident, but the fruit of God's eternal love, and that man is called to respond to this love in dialogue with Him.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Prologue. Logos: flesh

4th Advent Sunday (year A)

IV Sunday in Advent (year A) [21 December 2025]

May God bless us and the Virgin protect us! As we approach Christmas, the Word of God reminds us of the Lord's faithfulness even when the unfaithfulness of his people might weary him (first reading). The Gospel introduces us to Saint Joseph, the man who silently accepts and fulfils his mission as father of the Son of God.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (7:10-14)

It is around 735 BC. The kingdom of David has been divided into two states for two centuries: Samaria in the north and Jerusalem in the south, where Ahaz, a young king of twenty, reigns. The political situation is dramatic: the Assyrian empire, with its capital at Nineveh, dominates the region; the kings of Damascus and Samaria, already defeated by the Assyrians, now rebel and besiege Jerusalem to replace Ahaz with an allied ruler. The king panics: 'the heart of the king and the heart of the people were agitated like the trees of the forest by the wind' (Isaiah 7:2). The prophet Isaiah invites him to calm down and have faith: God has promised to keep David's dynasty alive; stability depends on trust in the Lord: if you do not believe, you will not remain steadfast. But Ahaz does not listen: he turns to idols and goes so far as to commit an atrocious act forbidden by the prophets, sacrificing his only son by passing him through the fire (cf. 2 Kings 16:3). He then decides to ask Assyria for help, a choice that entails the loss of political and religious independence. Isaiah strongly opposes this: it is a betrayal of the Covenant and of the liberation that began with Moses. In this context, Isaiah offers a sign: "Ask for a sign from the Lord your God." Ahaz responds hypocritically, pretending humility by not asking for it so as not to tempt the Lord, while he has already decided to entrust himself to Assyria. Isaiah replies rather harshly, saying not to weary 'my God', as if to indicate that Ahaz has now placed himself outside the Covenant. Despite the king's unfaithfulness, God remains faithful and, says Isaiah, 'the Lord himself will give you a sign': the young woman (the queen) is pregnant and the child will be called Immanuel, 'God with us'. This message from Isaiah is one of the classic texts of biblical messianism. Neither the enemies nor the king's sin can nullify the promise made by God to David. The child – probably the future king Hezekiah – will know how to choose good thanks to the Spirit of the Lord, and even before he grows up, the threat from Samaria and Damascus will disappear. In fact, shortly afterwards, the two kingdoms are destroyed by the Assyrians. Human freedom remains intact, and even Hezekiah will make mistakes; but Isaiah's prophecy affirms that nothing can prevent God's faithfulness to David's descendants. For this reason, throughout the centuries, Israel will wait for a king who will fully realise the name of Immanuel. The birth of the child is more than good news: it is an announcement of forgiveness. By sacrificing his son to the god Moloch, Ahaz compromised the promise made to David; but God does not withdraw his commitment. The birth of the new heir shows that God's faithfulness surpasses the unfaithfulness of men. The 'sign' thus takes on another encouraging messianic dimension, which we see more clearly in this Sunday's Gospel.

Important elements to remember: +Historical context: 735 BC, divided kingdom, threats from Syria, Samaria and Assyria. +Ahaz's panic and Isaiah's invitation to faith. +Serious unfaithfulness of the king: idolatry and sacrifice of his son. +Wrong political choice: alliance with Assyria. +Isaiah's sign: birth of the child called Immanuel. +Immediate fulfilment: destruction of Syria and Samaria by Assyria. +Central theme: the unfaithfulness of men does not nullify God's faithfulness. +Birth as an announcement of forgiveness and continuity of the Davidic promise.

Responsorial Psalm (23/24, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6)

The psalm takes us to the temple in Jerusalem: a great procession arrives at the gates and two choirs dialogue, asking: 'Who may ascend the mountain of the Lord? Who may stand in his holy place?' The image recalls Isaiah, who describes the thrice-holy God as a consuming fire before which no one could 'stand' without his help. The people of Israel have discovered that this totally 'Other' God also becomes the totally 'near' God, allowing man to remain in his presence. The psalm's answer is: 'Those who have clean hands and a pure heart, who do not turn to idols'. This is not primarily a matter of moralism, because the people know that they are admitted before God by grace, not by their own merit. Here, 'pure heart' means an undivided heart, turned solely to the one God; 'innocent hands' are hands that have not offered sacrifices to idols. The expression 'does not turn/literally does not lift up his soul' indicates not turning to empty deities: 'lifting up one's eyes' in the Bible means invoking, praying, recognising someone as God. This verse recalls the prophets' great struggle against idolatry. Isaiah had already opposed Ahaz in the eighth century; and even during the Exile in Babylon, the people - immersed in a polytheistic culture - were tempted to return to idols. The psalm, sung after the Exile, reminds us that the first condition of the Covenant is to remain faithful to the one God. Seeking the face of God is an image taken from the language of the court: only those who are faithful to the King can be admitted into his presence. Idols are defined as 'empty gods': Psalm 115 masterfully describes their nullity – they have eyes, mouths, hands, but they do not see, speak or act. Unlike these statues, God is alive and truly works. Fidelity to the one God is therefore the condition for receiving the blessing promised to the fathers and for entering into his plan of salvation. This is why Jesus will say: 'No one can serve two masters' (Matthew 6:24).

This fidelity, however, does not remain abstract: it concretely transforms life. The pure heart becomes a heart of flesh capable of eliminating hatred and violence; innocent hands become hands incapable of doing evil. The psalm says: "He will obtain blessing from the Lord, justice from God his salvation": this means both conforming to God's plan and living in right relationship with others. Here we already glimpse the light of the Beatitudes: Blessed are the pure of heart, for they will see God... blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice. The expression 'lift up your eyes', expressed here as 'those who do not turn to idols' (v. 4), returns in Zechariah and in the Gospel of John: 'They will look on the one they have pierced' (Jn 19:37), a sign of a new encounter with God.

Important elements to remember: +Scene in the temple with the dialogue of the choirs. +God is thrice holy and at the same time close: he allows man to 'stand' before him. +'Pure heart' and 'innocent hands' as fidelity to the one God, not idolatry and the prophets' constant struggle against idolatry (Ahaz, Exile). +Idols as 'empty gods'; criticism of Psalm 115. +Fidelity to the one God as the first condition of the Covenant, which has as its ethical consequences a righteous life, a renewed heart, and non-violent hands.

Second Reading from the Letter of St Paul to the Romans (1:1-7)

St Paul opens his letter to the Romans by summarising the whole Christian faith: the promises contained in the Scriptures, the mystery of Christ, his birth and resurrection, the free election of the holy people and the mission of the Apostles to the pagan nations. Writing to a community he has not yet met, Paul introduces himself with two titles: 'servant of Jesus Christ and apostle by calling', that is, sent, one who acts by mandate. He immediately attributes to Jesus the title of Christ, which means Messiah: to say 'Jesus Christ' is to profess that Jesus of Nazareth is the expected Messiah. Paul claims to have been 'chosen to proclaim the Gospel of God', the Good News: proclaiming the Gospel means proclaiming that God's plan is totally benevolent and that this plan is fulfilled in Jesus Christ. This Good News, says Paul, had already been promised in the prophets. Without the Old Testament, one cannot understand the New Testament because God's plan is unique, revealed progressively throughout history. The Resurrection of Christ is the centre of history, the heart of the divine plan from the beginning, as Paul also recalls in his letter to the Ephesians, where he speaks of God's will to recapitulate all things in Christ (Eph 1:9-10). 'According to the flesh': Jesus is a descendant of David, therefore a true man and Messiah. "According to the Spirit": Jesus is constituted Son of God "with power" through his Resurrection, and in the Resurrection God enthrones him as King of the new humanity. For Paul, this is the event that changes history because "if Christ has not been raised, then your faith is futile" (cf. 1 Cor 15:14). For this reason, he proclaims the Resurrection everywhere, so that "the name of Jesus Christ may be recognised", as he also writes in his letter to the Philippians (2:9-11), God has given him the Name above every other name, that of "Lord". Paul feels that his apostolic mission is "to bring about the obedience of faith in all peoples". "Obedience" is not servility, but trusting listening: it is the attitude of the child who trusts in the Father's love and welcomes his Word. Paul concludes with his typical greeting: 'Grace to you and peace from God', which is expressed in the priestly blessing in the Book of Numbers: grace and peace always come from God, but it is up to man to accept them freely.

Most important elements to remember: +Summary of the Christian faith: the promises are fulfilled in Christ, in the Resurrection, election and mission. +Paul's titles are servant and apostle, while the title 'Christ' is 'Messiah', which is a profession of faith. +The Gospel is God's merciful plan fulfilled in Christ. +Unity between the Old and New Testaments and Christ in his identity 'according to the flesh' and 'according to the Spirit': he is at the centre of God's plan from the beginning. +The Resurrection is the decisive event, and 'obedience of faith' is trusting listening. +Final blessing: grace and peace, in human freedom.

From the Gospel according to Matthew (1:18-24)

Matthew opens his Gospel with the expression: "Genealogy of Jesus Christ", that is, the book of the genesis of Jesus Christ, and presents a long genealogy that demonstrates Joseph's Davidic descent. Following the formula "A begot B", Matthew arrives at Joseph, but breaks with the pattern: he cannot say "Joseph begot Jesus"; instead, the evangelist writes: "Jacob begot Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called Christ" (Mt 1:16). This formula shows that the genealogy undergoes a change: for Jesus to be included in the line of David, his birth is not enough; Joseph must adopt him. The Son of God, in a certain sense, entrusts himself to the freedom of a man: the divine plan depends on Joseph's 'yes'. We are familiar with the Annunciation to Mary in Luke's Gospel, which is widely represented in art. Much less represented, however, is the Annunciation to Joseph, even though it is decisive: the human story of Jesus begins thanks to the free acceptance of a righteous man. The angel calls Joseph 'son of David' and reveals to him the mystery of Jesus' sonship: conceived by the Holy Spirit, yet recognised as his son. 'Do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife' means that Jesus will enter Joseph's house, and it will be he who will give him his name. Matthew also explains the meaning of the name Jesus: it means 'The Lord saves'. His mission is not only to free Israel from human power, but to save his people from sin. In Jewish tradition, the expectation of the Messiah included a total renewal: new creation, justice and peace. Matthew sees all this encapsulated in the name of Jesus. The text specifies: 'the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit'. There are two accounts of the virgin birth: this one by Matthew (Annunciation to Joseph) and the one by Luke (Annunciation to Mary). The Church professes this truth as an article of faith: Jesus is both true man, born of a woman, included in the lineage of David thanks to Joseph's free choice; and true Son of God, conceived by the Holy Spirit. Matthew links all this to Isaiah's prophecy: "The virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which means 'God-with-us'". The Greek translation of Isaiah (Septuagint), which Matthew quotes, uses the term 'virgin' (parthenos), while the Hebrew text uses almah, which means 'young woman' who is not yet married: even the ancient translation reflected the belief that the Messiah would be born of a virgin. Matthew insists: the child will be called Jesus (the Lord saves), but the prophet calls him Emmanuel (God-with-us). This is not a contradiction: at the end of Matthew's Gospel, Jesus will say, 'I am with you always, even unto the end of the world' (Mt 28:20). His name and his mission coincide: to save means to be with man, to accompany him, never to abandon him. Joseph believed and welcomed the presence of God. As Elizabeth said to Mary, 'Blessed is she who believed' (Lk 1:45), so we can say, 'Blessed is Joseph who believed: thanks to him, God was able to fulfil his plan of salvation'. Matthew uses the word "genesis" twice (Mt 1:1, 18), as in the book of Genesis when speaking of the descendants of Adam. This suggests that the entire history of humanity is recapitulated in Jesus: he is the New Adam, as St Paul will say.

Most important elements to remember: Break in the genealogy: Jesus is not "begotten" by Joseph but through adoption fulfils the plan of salvation. Joseph's freedom is fundamental in the fulfilment of God's plan. Title "son of David" and Joseph's legal role. Name of Jesus = "The Lord saves" mission of salvation from sins. +Virgin conception: mystery of faith, true man and true Son of God. +Quotation from Isaiah 7:14 according to the Greek translation ("virgin"). +Jesus and Emmanuel: salvation as the constant presence of God. +Parallel with Elizabeth's beatitude: Joseph's faith. +Jesus as the "New Adam" according to the reference to "Genesis".

Commentary by St Augustine, Sermon 51, on the Incarnation

"Joseph was greater in silence than many in speech: he believed the angel, accepted the mystery, protected what he did not fully understand. In him we see how faith does not consist in understanding everything, but in trusting God who works in secret." Augustine thus emphasises Joseph's unique role: his faith is trusting obedience; he welcomes Christ without possessing him; he becomes the guardian of the mystery that saves the world.

+Giovanni D'Ercole

Christmas: Easter. Breath for me

Meaning and Value of Doubt. Annunciation to Joseph

3rd Advent Sunday (year A)

Third Sunday in Advent (year A) [14 December 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us! "Rejoice always in the Lord... the Lord is near." The message of this third Sunday of Advent is the announcement of the joy of Christmas approaching. Advent teaches us to wait with patient hope for Jesus, who will surely come.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (35:1...10)

This passage comes from Isaiah's Little Apocalypse, known as the "Minor Apocalypse" (cc34-35), probably written by an anonymous author, and tells of the joyful return of Israel from exile in Babylon. We are in the period when the people suffered the sack of Jerusalem and spent over fifty years away from their land, experiencing humiliation and suffering that would discourage even the strongest. Isaiah, who lived in the 6th century BC during the exile in Babylon, reassures the frightened people: 'Behold your God: vengeance is coming, divine reward. He is coming to save you'. The result will be the liberation of the suffering: the blind will see, the deaf will hear, the lame will leap for joy, the mute will shout for joy. The people have suffered years of domination, deportation with humiliation and many trials, including religious ones: a time that discourages and makes them fear for the future. The author uses the expression 'God's vengeance', which may surprise us today. But here, vengeance is not punishment on men: it is the defeat of the evil that oppresses them and the liberation that God gives. God intervenes personally to save, redeem and restore dignity: the blind will see, the deaf will hear, the lame will leap and the mute will shout for joy. The return from exile is described as a triumphal march through the desert: the arid landscape is transformed into fertile and lush land, as beautiful as the mountains of Lebanon, the hills of Carmel and the plain of Sharon, symbols of abundance and beauty in the land of Israel. This journey shows that even the hardest trials can become a path of joy and hope when God intervenes. The desert, a symbol of hardship and trial, is thus transformed into a path of joy and hope thanks to God's intervention. The liberated people are called 'redeemed' and liberation is compared to 'redemption' in Jewish law: just as a close relative would release a debt or redeem a slave, God himself is our 'Go'el', the Relative who frees those who are oppressed or prisoners of evil. In this sense, redemption means liberation: physical, moral and spiritual. Singing 'Alleluia' means recognising that God leads us from servitude to freedom, transforming despair into joy and the desert into blossoming. This text reminds us that God never abandons us: even in the most difficult moments, his mercy and love free us and give us hope again. It shows how the language of the Bible can transform words that seem threatening into promises of salvation and hope, reminding us that God always intervenes to free us and restore our dignity.

Main elements +Context: Babylonian exile, Israel far from the land, anonymous author. +Isaiah's Little Apocalypse: prophecy of hope and return to the promised land. +God's vengeance: defeat of evil, not punishment of men. +Concrete liberation: the blind, deaf, lame, mute and prisoners redeemed. +The desert will blossom: difficulties transformed into joy and beauty. +Redemption: God as Go'el, liberator of the oppressed. +Alleluia: song of praise for the liberation received. +Spiritual message: God intervenes to free us and give us hope even in the hardest moments.

*Responsorial Psalm (145/146, 7-8, 9-10

This psalm, a 'psalm of Alleluia', is a song full of joy and gratitude, written after the return of the people of Israel from exile in Babylon, probably for the dedication of the rebuilt Temple. The Temple had been destroyed in 587 BC by Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon. In 538 BC, after the conquest of Babylon by the Persian king Cyrus, the Jews were allowed to return to their land and rebuild the Temple. The reconstruction was not easy due to tensions between those returning from Babylon and those who had remained in Israel, but thanks to the strength of the prophets Haggai and Zechariah, the work was completed in 515 BC, under King Darius. The dedication of the new Temple was celebrated with great joy (Ezra 6:16). The psalm reflects this joy: Israel recognises that God has remained faithful to the Covenant, as he did during the Exodus. God is the one who frees the oppressed, breaks the chains, gives bread to the hungry, gives sight to the blind and lifts up the weak. This image of God, a God who takes the side of the poor and feels compassion ('mercy' indicates as if the bowels were trembling), was not taken for granted in ancient times. It is Israel's great contribution to the faith of humanity: to reveal a God of love and mercy. The psalm expresses this by saying that the Lord supports the widow and the orphan. The people are invited to imitate God in the same mercy, and the Law of Israel contains many rules for the protection of the weak (widows, orphans, foreigners). The prophets judged Israel's fidelity to the Covenant on the basis of this behaviour. At a deeper level, the psalm shows that God frees us not only from external oppression, but also from internal oppression: spiritual hunger finds its food in the Word; inner blindness is illuminated; the chains of hatred, pride and jealousy are broken. Although we do not see it here, this psalm is actually framed by the word 'Alleluia', which according to Jewish tradition means to sing the praise of God because He leads from slavery to freedom, from darkness to light, from sadness to joy. We Christians read this psalm in the light of Jesus Christ: He gave bread to his contemporaries and continues to give the "bread of life" in the Eucharist; He is the light of the world (Jn 8:12); in his resurrection, he definitively freed humanity from the chains of death. Finally, since man is created in the image of God, every time he helps a poor person, a sick person, a prisoner, a stranger, he manifests the very image of God. And every gesture made "to the least" contributes to the growth of the Kingdom of God. A catechumen, reading about the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves, asked, "Why doesn't Jesus do this today for all the hungry?" And after a moment she replied, "Perhaps he is counting on us to do it."

Important elements to remember +Historical context: psalm written after the return from exile and the reconstruction of the Temple (587–515 BC). +Central theme: the joy of the people for God's faithfulness and their liberation. +Revelation of God: God is merciful and defends the oppressed, the poor, the weak. +Commitment of the people: to imitate God in works of mercy towards all the oppressed. +Spiritual reading: God frees us from inner chains (hatred, pride, spiritual blindness). +Alleluia: symbol of the passage from slavery to freedom and from sadness to joy. +Christian reading: fulfilment in Christ, who gives true bread, enlightens, liberates, saves. +Image of God in man: every gesture of love towards the most fragile makes the image of God visible. +Christian responsibility: God also counts on our commitment to nourish, liberate and support those who suffer.

*Second Reading from the Letter of St James the Apostle (5:7-10)

Christian tradition recognises three figures named James who were close to Jesus: James the Greater, son of Zebedee and brother of John, with an impetuous character, present at the Transfiguration and in Gethsemane; James, son of Alphaeus, one of the Twelve; James, 'brother/cousin' of the Lord, leader of the Church of Jerusalem and probable author of the Letter of James. The text highlights a fundamental theme for the early Christians: the expectation of the coming of the Lord. Like Paul, James always looks to the horizon of the final fulfilment of God's plan. It is significant that at the very beginning of Christian preaching, the end of the world was most ardently desired, perhaps because the Resurrection had given a taste of future glory. In this expectation, James repeats a crucial invitation: patience, a word which in the original Greek (makrothyméo) means 'to have long breath, to have a long spirit'. Waiting for the coming of the Lord is a long-distance race, not a sprint: faith must learn to endure over time. When the early Christians realised that the parousia was not coming immediately, waiting became a true test of fidelity.

To live this endurance, James offers two models: the farmer, who knows the rhythm of the seasons, trusting in God who sends rain 'in its season' (Deut 11:14), and the other model: the prophets, who endured hostility and persecution to remain faithful to their mission. James asks Christians to have stamina (perseverance/patience) and a steadfast heart ("Strengthen your hearts"). In verse 11, which follows this text, James also quotes Job, the only case in the New Testament, as the supreme example of perseverance: those who remain steadfast like him will experience the Lord's mercy. Patience is not only personal: it is lived out in community relationships. James takes up Jesus' teaching: do not complain about one another, do not judge one another, do not murmur. 'The Judge is at hand': only God truly judges, because he sees the heart. Man easily risks confusing wheat and weeds. The lesson is also for us: we often lack the breath of hope, and at the same time we give in to the temptation to judge. Yet Jesus' words about the speck and the log remain relevant today.

Important points to remember: + Of the three James, it is James the Greater, the son of Alphaeus, the 'brother' of the Lord, who is the probable author of this Letter, which reflects the central theme of waiting for the coming of the Lord. + Patience is repeated several times and is understood as 'long breath', an endurance race. + The initial Christian expectation was very intense: it was thought that Christ's return was imminent. + Two models of perseverance: the farmer (trust in God's timing) and the prophets (courage in mission). + v.11 not in this text but immediately after John

cites Job as an example of endurance: the only citation in the New Testament, a symbol of perseverance in trials. +Community mission: do not judge, do not murmur, do not complain because 'the Judge is at the door'. He invites us to live knowing that only God judges rightly. +The danger today is also a lack of spiritual breath and the risk of judging others.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (11:2-11)

Last Sunday we saw John the Baptist baptising along the Jordan and announcing: 'After me comes one'. When Jesus asked to be baptised, John recognised him as the expected Messiah, but the months passed and John was put in prison by Herod around the year 28, at which time Jesus began his public preaching in Galilee. Jesus began his public life with famous discourses, such as the Sermon on the Mount and the Beatitudes, and with many healings. However, his behaviour was strange in the eyes of the people: he surrounded himself with "unreliable" disciples (publicans, people of different origins and characters); he was not an ascetic like John, he ate and drank like everyone else, and he showed himself among the common people; he never claimed the title of Messiah, nor did he seek power. From prison, John received news from those who kept him informed and began to doubt: 'Have I been deceived? Are you the Messiah?' This question is crucial because it concerns both John and Jesus, who was forced to confront the expectations of those who awaited him. Jesus does not answer with a yes or no, but quotes the prophecies about the works of the Messiah: the blind regain their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor receive the good news (Isaiah 35:5-6; 61:1). With these words, Jesus invites John to see for himself whether he is doing the works of the Messiah, confirming that yes, he is the Messiah, even if his manners seem strange. The true face of God is revealed in his service to humanity, not in accordance with expectations of power or glory. Finally, Jesus praises John, saying that he is blessed because he "does not find cause for scandal in me." John sets an example of faith: even in doubt, he does not lose confidence and seeks the truth directly from Jesus himself. Jesus concludes by explaining that John is the greatest of the prophets because he paves the way for the Messiah, but with the coming of Jesus, even the least in the Kingdom of Heaven is greater than John, emphasising that the content of Christ's message exceeds all human expectations: "The Word became flesh and dwelt among us".

Important elements to remember +John the Baptist announces the Messiah and baptises along the Jordan. +Jesus begins his public life after John's arrest, in Galilee, with speeches and miracles. +Jesus' "strange" behaviour: he associates with everyone, even the most marginalised, does not claim titles or power, eats and presents himself like ordinary people.+John's doubts: he sends his disciples to ask if Jesus is truly the Messiah. + Jesus' response: he cites the prophetic works of the Messiah (healings, liberations, proclamation to the poor).+ John's active faith: he does not remain in doubt, but asks Jesus directly for clarification. + Joy and surprise: the face of God is revealed in the service of man, not according to traditional expectations. + John as precursor: the greatest of the prophets, but with Jesus, the smallest in the Kingdom is the greatest. + Final message: Christ is the Word incarnate, the fulfilment of God's promises.

*Here is a quote from St Gregory the Great in Homily 6 on the Gospels, commenting on the episode: "John does not ignore who Jesus is: he points to him as the Lamb of God. But, sent to prison, he sends his disciples not to know him, but so that they may learn from Christ what he already knew. John does not seek to be taught, but to teach. And Christ does not respond with words, but with deeds: he makes it clear that he is the Messiah not by saying so, but by showing the works announced by the prophets." He adds: "The Lord proclaims blessed those who are not scandalised by him, because in him there is greatness hidden beneath a humble appearance: those who are not scandalised by his humility recognise his divinity." This commentary perfectly illuminates the heart of the Gospel: John does not doubt for himself, but to help his disciples recognise that Jesus is the expected Messiah, even though he presents himself in a surprising and humble way.

+Giovanni D'Ercole

Immaculate Conception

Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary [8 December]

Biblical texts: Gn 3:9–20; Ep 1:3–12; Lk 1:26–38 May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us! Instead of commenting on the readings, I propose a theological and spiritual meditation on the Immaculate Conception, starting with St Paul and referring to the tradition of the Church and the liturgy.

1. Saint Paul and Mary: a hidden but real bond Although Paul speaks almost nothing directly about the Virgin Mary, his teaching on the election, holiness and predestination of Christians (Eph 1:4-11) deeply illuminates the mystery of Mary. Saint Paul affirms that all the baptised are chosen, holy and immaculate. Applying this to Mary, we understand that what is true for the whole Church is realised in her in a perfect and anticipated way.