don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

1. In acknowledging the centrality of love, Christian faith has retained the core of Israel's faith, while at the same time giving it new depth and breadth. The pious Jew prayed daily the words of the Book of Deuteronomy which expressed the heart of his existence: “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God is one Lord, and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul and with all your might” (6:4-5). Jesus united into a single precept this commandment of love for God and the commandment of love for neighbour found in the Book of Leviticus: “You shall love your neighbour as yourself” (19:18; cf. Mk 12:29-31). Since God has first loved us (cf. 1 Jn 4:10), love is now no longer a mere “command”; it is the response to the gift of love with which God draws near to us..

18. Love of neighbour is thus shown to be possible in the way proclaimed by the Bible, by Jesus. It consists in the very fact that, in God and with God, I love even the person whom I do not like or even know. This can only take place on the basis of an intimate encounter with God, an encounter which has become a communion of will, even affecting my feelings. Then I learn to look on this other person not simply with my eyes and my feelings, but from the perspective of Jesus Christ. His friend is my friend. Going beyond exterior appearances, I perceive in others an interior desire for a sign of love, of concern. This I can offer them not only through the organizations intended for such purposes, accepting it perhaps as a political necessity. Seeing with the eyes of Christ, I can give to others much more than their outward necessities; I can give them the look of love which they crave. Here we see the necessary interplay between love of God and love of neighbour which the First Letter of John speaks of with such insistence. If I have no contact whatsoever with God in my life, then I cannot see in the other anything more than the other, and I am incapable of seeing in him the image of God. But if in my life I fail completely to heed others, solely out of a desire to be “devout” and to perform my “religious duties”, then my relationship with God will also grow arid. It becomes merely “proper”, but loveless. Only my readiness to encounter my neighbour and to show him love makes me sensitive to God as well. Only if I serve my neighbour can my eyes be opened to what God does for me and how much he loves me. The saints—consider the example of Blessed Teresa of Calcutta—constantly renewed their capacity for love of neighbour from their encounter with the Eucharistic Lord, and conversely this encounter acquired its real- ism and depth in their service to others. Love of God and love of neighbour are thus inseparable, they form a single commandment. But both live from the love of God who has loved us first. No longer is it a question, then, of a “commandment” imposed from without and calling for the impossible, but rather of a freely-bestowed experience of love from within, a love which by its very nature must then be shared with others. Love grows through love. Love is “divine” because it comes from God and unites us to God; through this unifying process it makes us a “we” which transcends our divisions and makes us one, until in the end God is “all in all” (1 Cor 15:28).

[Deus Caritas est, nn.1.18]

1. "If any one says, "I love God', and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen, cannot love God whom he has not seen. And this commandment we have from him, that he who loves God should love his brother also" (1 Jn 4: 20-21).

The theological virtue of charity, of which we spoke in our last catechesis, is expressed in two dimensions: love of God and love of neighbour. In both these dimensions it is the fruit of the dynamism of Trinitarian life within us.

Indeed, love has its source in the Father; it is fully revealed in the Passover of the crucified and risen Son, and is infused in us by the Holy Spirit. Through it God lets us share in his own love.

If we truly love with the love of God we will also love our brothers or sisters as God loves them.

This is the great newness of Christianity: one cannot love God if one does not love one's brethren, creating a deep and lasting communion of love with them.

2. In this regard, the teaching of Sacred Scripture is unequivocal. The Israelites were already encouraged to love one another: "You shall not take vengeance or bear any grudge against the sons of your own people, but you shall love your neighbour as yourself" (Lv 19: 18). At first this commandment seems restricted to the Israelites, but it nonetheless gradually takes on an ever broader sense to include the strangers who sojourn among them, in remembrance that Israel too was a stranger in the land of Egypt (cf. Lv 19: 34; Dt 10: 19).

In the New Testament this love becomes a command in a clearly universal sense: it presupposes a concept of neighbour that knows no bounds (cf. Lk 10: 29-37) and is even extended to enemies (cf. Mt 5: 43-47). It is important to note that love of neighbour is seen as an imitation and extension of the merciful goodness of the heavenly Father who provides for the needs of all without distinction (cf. ibid., v. 45). However it remains linked to love of God: indeed the two commandments of love are the synthesis and epitome of the law and the prophets (cf. Mt 22: 40). Only those who fulfil both these commandments are close to the kingdom of God, as Jesus himself stresses in answer to a scribe who had questioned him (cf. Mk 12: 28-34).

3. Abiding by these guidelines which link love of neighbour with love of God and both of these to God's life in us, we can easily understand how love is presented in the New Testament as a fruit of the Spirit, indeed, as the first of the many gifts listed by St Paul in his Letter to the Galatians: "The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control" (Gal 5: 22).

Theological tradition distinguishes, while correlating them, between the theological virtues, the gifts and the fruits of the Holy Spirit (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, nn. 1830-1832). While the virtues are dispositions permanently conferred upon human beings in view of the supernatural works they must do, and the gifts perfect both the theological and the moral virtues, the fruits of the Spirit are virtuous acts which the person accomplishes with ease, habitually and with delight (cf. St Thomas, Summa theologiae, I-II, q. 70 a. 1, ad 2). These distinctions are not contrary to what Paul says, speaking in the singular of the fruit of the Spirit. In fact, the Apostle wishes to point out that the fruit par excellence is the same divine charity which is at the heart of every virtuous act. Just as sunlight is expressed in a limitless range of colours, so love is manifest in the multiple fruits of the Spirit.

4. In this regard, it says in the Letter to the Colossians: "Above all these put on love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony" (3: 14). The hymn to love contained in the First Letter to the Corinthians (cf. 1 Cor 13) celebrates this primacy of love over all the other gifts (cf. vv. 1-3), and even over faith and hope (cf. v. 13). The Apostle Paul says of it: "Love never ends" (v. 8).

Love of neighbour has a Christological connotation, since it must conform to Christ's gift of his own life: "By this we know love, that he laid down his life for us; and we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren" (1 Jn 3: 16). Insofar as it is measured by Christ's love, it can be called a "new commandment" by which the true disciples may be recognized: "A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another; even as I have loved you, that you also love one another. By this all men will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another" (Jn 13: 34-35). The Christological meaning of love of neighbour will shine forth at the second coming of Christ. Indeed at that very moment, it will be seen that the measure by which to judge adherence to Christ is precisely the daily demonstration of love for our neediest brothers and sisters: "I was hungry and you gave me food ..." (cf. Mt 25: 31-46).

Only those who are involved with their neighbour and his needs concretely show their love for Jesus. Being closed and indifferent to the "other" means being closed to the Holy Spirit, forgetting Christ and denying the Father's universal love.

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 20 October 1999]

It is an invitation to discover "the idols hidden in the many folds that we have in our personality", to "chase away the idol of worldliness, which leads us to become enemies of God" that Pope Francis addressed during mass this morning, Thursday 6 June, in the chapel of the Domus Sanctae Marthae [...] The exhortation to undertake "the path of love to God", to set out on "the way to arrive" to his kingdom was the crowning of a reflection centred on the passage from Mark's Gospel (12:28-34), in which Jesus responds to the scribe who questions him on which is the most important of all the commandments. The Pontiff's first remark is that Jesus does not answer with an explanation but using the word of God: "Listen, Israel! The Lord our God is the only Lord'. These, he said, "are not Jesus' words". In fact, he addresses the scribe as he had addressed Satan in the temptations, 'with the word of God; not with his words'. And he does so using "the creed of Israel, that which the Jews every day, and several times a day, say: Shemà Israel! Remember Israel, to love only God'.

In this regard, the Pontiff confided that he believed that the scribe in question perhaps "was not a saint, and was going a little to test Jesus or even to make him fall into a trap". In short, his intentions were not the best, because "when Jesus responds with the word of God" it means that there is a temptation involved. "And this is also seen when the scribe says to him: you have said well master," giving the impression of approving his answer. That is why Jesus replies to him "you are not far from the Kingdom of God. You know well the theory, you know well that this is so, but you are not far off. You still lack something to get to the Kingdom of God'. This means that there is "a path to get to the Kingdom of God"; one must "put this commandment into practice".

Consequently, "the confession of God is made in life, in the journey of life; it is not enough," the Pope warned, "to say: I believe in God, the only one"; but one must ask oneself how one lives this commandment. In fact, we often continue to "live as if he were not the only God" and as if there were "other divinities at our disposal". This is what Pope Francis calls "the danger of idolatry", which "is brought to us with the spirit of the world". And Jesus was always clear on this: 'The spirit of the world no'. So much so that at the Last Supper he "asks the Father to defend us from the spirit of the world, because it leads us to idolatry". The Apostle James, in the fourth chapter of his letter, also has very clear ideas: he who is a friend of the world is an enemy of God. There is no other option. Jesus himself had used similar words, the Holy Father recalled: 'Either God or money; one cannot serve money and God'.

For Pope Francis, it is the spirit of the world that leads us to idolatry and does so with cunning. "I am sure," he said, "that none of us go in front of a tree to worship it as an idol"; that "none of us have statues to worship in our homes". But, he warned, 'idolatry is subtle; we have our hidden idols, and the road of life to get there, to not be far from the Kingdom of God, is a road that involves discovering hidden idols'. And it is a challenging task, since we often keep them 'well hidden'. As Rachel did when she fled with her husband Jacob from her father Laban's house, and having taken the idols from him, she hid them under the horse on which she sat. So when her father invited her to get up, she replied 'with excuses, with arguments' to hide the idols. We do the same, according to the Pope, who keep our idols 'hidden in our mounts'. That is why 'we must seek them out and we must destroy them, as Moses destroyed the golden idol in the desert'.

But how do we unmask these idols? The Holy Father offered a criterion for evaluation: they are those who make people do the opposite of the commandment: "Listen, Israel! The Lord our God is the only Lord'. Therefore "the way of love to God - you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and all your soul - is a way of love; it is a way of faithfulness". So much so that "the Lord likes to compare this road with nuptial love. The Lord calls his Church, bride; our soul, bride'. That is to say, he speaks of "a love that so closely resembles nuptial love, the love of fidelity". And the latter requires us "to cast out idols, to discover them", because they are there and they are well "hidden, in our personality, in our way of life"; and they make us unfaithful in love. In fact, it is no coincidence that the Apostle James, when he admonishes: 'he who is a friend of the world is an enemy of God', begins by rebuking us and using the term 'adulterers', because 'he who is a friend of the world is an idolater and is not faithful to the love of God'.

Jesus therefore proposes "a way of faithfulness", according to an expression that Pope Francis finds in one of the Apostle Paul's letters to Timothy: "If you are not faithful to the Lord, he remains faithful, because he cannot deny himself. He is full fidelity. He cannot be unfaithful. So much love he has for us". Whereas we, 'with the little or not so little idolatries we have, with our love for the spirit of the world', can become unfaithful. Faithfulness is the essence of God who loves us. Hence the concluding invitation to pray like this: 'Lord, you are so good, teach me this way to be each day less distant from the kingdom of God; this way to cast out all idols. It is difficult," the Pontiff admitted, "but we must begin".

[Pope Francis, S. Marta homily, in L'Osservatore Romano 07/06/2013]

Lk 11:14-23 (14-26)

Prejudice affects the union, and no one can kidnap Jesus, holding him hostage. He’s the strong man that no perched citadel can stem.

Those who fear losing command and their contrived prestige have already lost. There is no armor or booty that can resist and remain.

There is no custom, compromise or gendarmerie which can withstand the siege of Freedom in Christ.

The Scriptures form an inseparable unity. However, only in Him does Tradition not block charisms, doesn’t diminish us, doesn’t cause anxiety, nor lead to scruple - but acquires its vital implication.

In fact, friendship with the Risen is extraordinarily original, and has respect for uniqueness. It’s in a continuity and at the same time in the break with the ancient mind. Vital Monotheism of a new Spirit welcoming the Gifts.

The authorities were attached to the fake prestige they had gained and were very concerned that Jesus was faithful to his unique task.

In Him, the activity of his Church works also exorcisms: it emancipates from dehumanizing forces, conditioning, structures. It moves not on a legalistic level, but on an operative belief-love that guarantees each one that path of spontaneity and fullness desired within.

By overcoming ancient convictions that put people's reality in parentheses and accentuated their blocks, the community of sons is called to become the ‘power’ of God.

Clear sign of the enterprising presence of the personal and diligent Spirit [«the finger of God»: v.20] which surpasses empty and indolent spirituality.

And why does Jesus emphasize that the second fall is more ruinous than the first (vv.24-26)?

While Luke was writing the Gospel, in the mid-80s there were not a few defections due to persecutions.

Believers were disheartened, dismayed by social disdain - so many saw the enthusiasm of the early days pale.

In no way manners of doing were shifting the normal frame of reference, while difficulties were some people discouraging.

Afflictions that seemed to put a tombstone on the hope of actually building an alternative society.

But the Gospel reiterates that a neutral attitude (v.23) at a safe distance is not envisaged. In the vocation there are no half measures: only clear choices, and no repressed needs.

The baptized in Christ lives full attitudes, regardless of favorable circumstances or not; he remains far from childish fears, enjoys a free heart. He is firm in action.

He foresees that he may be ‘wayfarer’, placed under siege by the system that does not tolerate real changes (v.22).

In this he rests, always involving his own natural and character roots - where the primordial energies of the soul and the innate dreams [that heal and guide] are kept.

For that matter, his itinerary is convoluted, “against traffic”, and surely punctuated with hard lessons. But the very difficult moments will be further ‘calls’ for transformation.

Reborn in Christ who protects and promotes our exceptional originality, we cannot "die" by losing the once-in-a-lifetime Encounter and returning to being photocopies - without Exodus of the soul.

Free toward the Promised Land that belongs to us, we seek not circumstantial perfections, but Fullness.

[Thursday 3rd wk. in Lent, March 12, 2026]

Lk 11:14-23 (14-26)

Prejudice undermines the union, and no one can put Jesus under hijacking, holding him hostage. He is the fortress that no entrenched citadel can hold.

He who fears losing his command and losing his own contrived prestige has already lost. There is no armour or booty that can hold.

No custom or compromise or gendarmerie to trust can withstand the siege of Liberty in Christ.

The Scriptures form an inseparable unity. However, only in Him does Tradition not block charisms, diminish us, cause anxiety, or lead to scruples - rather, it acquires its vital implication.

Friendship with the Risen One is indeed extraordinarily original, and has respect for uniqueness. It lies in a continuity and at the same time in a break with the ancient mind.

It is the vital monotheism of a new Spirit, which welcomes the Gifts.

Whoever does not strive to expand the creative work of the Father, whoever does not try his utmost to understand and enliven situations or persons - even with respect to eccentricities that previously had no place and seemed incommunicable - hovers over illusions, disperses himself, undermines the whole environment.

The Tao Tê Ching (LXV) says: "In ancient times those who well practised the Tao did not make the people discerning with it, but with it they strove to make them dull: the people with difficulty govern themselves, because their wisdom is too much.

Ordinary people accept chaos, they do not avoid life.

Missionaries are trained to find in every toil, in every error or imperfection, a new arrangement, ordered and secret. Nothing is external.

In every uncertainty there is a certainty, in every insecurity a greater security, in every shadowed side an unexpected Pearl, in every disorder a cosmos: this is the secret of life, of happiness, of the experience of Faith.

The authorities were attached to the fake prestige they had won and worried that Jesus would be faithful to his unique task, and could succeed in taking from them the people lured - but now liberated - by the religion of fears.

He [his community] remained more convincing because he fulfilled the Kingdom, he began to show it; not in fantasies of cataclysms that put souls on a leash, but alive and efficient, step by step, person by person.

It met the yearning for human wholeness that inhabited every heart, so it did not rely on obsessions and paroxysms or on the Law, but on the real good, the healing, the ever-changing life.

The cure of individual and relational infirmities was no longer a secondary matter: thus, for example, the liberation of an unhappy individual began to seem an event that had absolute, definitive value.

The scene on earth could no longer be dominated by adapted catechisms and a pious custom that denied everything but fears.

In short, Christ himself is the strong man who sees far, the sign of God's efficacious coming among men.

With him the reign of illusions and fixed positions declines; the world contrary to the unravelling of concrete existence takes over, respecting the uniqueness and conviviality of differences.

The activity of his Church works exorcisms: it emancipates from dehumanising forces-conditions-structures.

In the Lord, it moves not on a legalistic plane, but on a plane of operative belief-love, which guarantees to each one that path of spontaneity and fullness desired in the inner self.

Today too, the fraternal community must become aware of being an instrument of redemption and the energetic presence of God among ordinary women and men, from all walks of life.

Conspect, existence, participation. To lead, to accompany towards a present-future that gives breath not only to the group, but also to the individual inclination, by name.

Children's assemblies are empowered by grace and vocation to untie knots and overcome fences of mentality - thus giving rise to a sympathetic environment that accepts wayfarers.

This is the principle, non-negotiable horizon of the Faith.

By overcoming old fixed convictions that bracket the reality of people and accentuate their blockages, the community of children in the Risen One is called to become the power of God, for each one.

It is urged to become a clear sign of the enterprising closeness of the personal and diligent Holy Spirit ["the finger of God": v.20].

Contact that overcomes the reassuring and empty spirituality, as well as the superficial, indolent distraction of devotion according to custom imposed by convention or fashion, and by chains of command.

But why does Jesus emphasise that the second fall is more ruinous than the first (vv.24-26)?

The believer's mind can be emptied of the great step of the living Christ - which it has previously practised and recognised within itself and in the mission.

In this way, it does not remain focused on something useful, vital and splendid: weakened, it is lost.

While Lk wrote the Gospel, in the mid-1980s there were quite a few defections due to persecution.

Believers were disheartened, dismayed by social scorn - so many saw the enthusiastic intoxication of the early days pale.

Love could not be banked, but several brethren in congregations already coming from paganism, after an initial conversion experience, preferred to return to their former life, to imitating models, to easy thinking, to the lure and approval of the crowds.

Falling back and resigning themselves to the forces at work, some abandoned the position of inner autonomy gained through the liberating action from idols, fostered by the wise and prayerful life in the fraternal community.

Then they also sought individual reparation and revenge for the difficult years spent in being faithful to their vocation, in that stimulus to grow together through the exchange of gifts and resources.

Lk warns: it is normal that there are as many nights as days.

One understands the stress of wandering to approach the infinity of the soul, the next (even of community), the competitive reality - but beware... a second fall would be worse than the first.

The person once restored to himself and who gives up everything demoralised, would then give way to general disillusionment, to a more global lack of judgement, awareness, and trust.

This still happens today because of particular impulses, discouragement, or precipitation, after seeing ideals shattered by imperfect circumstances.

Or due to the fatigue of facing discoveries and evolutions that always call everything into question - in the long time it takes for one to be patiently consistent with one's deepest codes.

So those who allow themselves to be shattered would easily return to seeking the go-ahead of others.

He would yearn for that alignment that hides conflicts and makes one tremble less - because the ancient conviction that has become a modus vivendi does not shift one's ways, nor the normal frame of reference.

The difficulties made some people's arms fall off, and this seemed to put a tombstone on the hope of actually building an alternative society without doing too much harm to themselves.

But the Gospel reiterates that there is no neutral attitude (v.23) at a safe distance.

There are no half-measures: only clear choices, and no suppressed needs.

Integrated yes: contradictory sides always dwell in the heart, there is no need to be dismayed by this.

Opposite states of being are a richness that completes us.

On the contrary, one becomes neurotic precisely when reductionist manias or monothematic (club) needs prevail and stifle the multifaceted Calling - which although chiselled for uniqueness, never becomes one-sided.

To live fully, freely and happily, it is good to be ourselves, aware of what we are: perfect children.

Indefectible women and men, for our task in the world.

So we can overlook the discomfort of the insults of those who scold and levell us, let them flow away - and dispense with chasing after praise.

The man of Faith has experienced and knows the essential: it is life that conquers death, not vice versa. So he neglects obsessions, even cloaked in the sacred; and he does not let the spirit wear him down.

It enjoys a critical conscience that knows how to place immediate results in the background; thus it regenerates. It ceaselessly reactivates and does not eradicate strength.

The baptised in Christ lives full attitudes, in order to authenticity and totality of being. This, regardless of favourable or unfavourable circumstances.

The friend of the Risen Jesus remains distant from childish fears, enjoys a free heart; he is firm in action.

He anticipates that he may be a wayfarer, besieged by the hysterical system, which does not tolerate real change (v.22).

In this he rests, always calling upon his natural and character roots - where the primordial energies of the soul and the innate (non-derivative) dreams that heal and guide are stored.

After all, his journey is against the grain and will surely be punctuated with hard lessons.

But the cliché is all induced silliness; it tries to invade us with recriminations without specific weight: attempts at blocking with no future.

No wonder the acolytes of the conformist world defend themselves in every way.

And attacks with that standard - socially 'appreciative' - vociferousness that attempts to accentuate intimate and personal conflicts.

Always with great means at their disposal, and by appealing to guilt.

We will still walk the Lord's way, even when urged on by doubts and indecisions. Without retreating, even when we feel lost - but with the taste of gain even in loss.

The most difficult moments will be further calls to transformation.

And in every circumstance we will experience the taste of the victory of full life over the power of evil and the imitative, other people's, banal cultural tenor.

Here - in fidelity to our own inner world that wants to express itself, and in a change of style or imagination in our approaches - we solve the real problems and all issues, in a rich, personal way.

Reborn in Christ who protects and promotes from exceptional originality, we cannot "die" by losing the essence and the unrepeatable Encounter.

We would return to identifying ourselves in roles, as photocopies - without the Journey of the soul.

Free towards the promised land that belongs to us, we do not seek perfection of circumstance, but fullness.

To internalise and live the message:

Who and what activates me or loses me?

Is Jesus my Lord, or am I [status, my group, 'proper' manners, even religious influences] His master?

How do I deal with situations?

Do I open breaches and not disperse, in harmony with the old and new Voice of the soul, and in the Spirit?

Another aspect of Lenten spirituality is what we could describe as “combative“, as emerges in today’s “Collect”, where the “weapons” of penance and the “battle” against evil are mentioned.

Every day, but particularly in Lent, Christians must face a struggle, like the one that Christ underwent in the desert of Judea, where for 40 days he was tempted by the devil, and then in Gethsemane, when he rejected the most severe temptation, accepting the Father’s will to the very end.

It is a spiritual battle waged against sin and finally, against Satan. It is a struggle that involves the whole of the person and demands attentive and constant watchfulness.

St Augustine remarks that those who want to walk in the love of God and in his mercy cannot be content with ridding themselves of grave and mortal sins, but “should do the truth, also recognizing sins that are considered less grave…, and come to the light by doing worthy actions. Even less grave sins, if they are ignored, proliferate and produce death” (In Io. evang. 12, 13, 35).

Lent reminds us, therefore, that Christian life is a never-ending combat in which the “weapons” of prayer, fasting and penance are used. Fighting against evil, against every form of selfishness and hate, and dying to oneself to live in God is the ascetic journey that every disciple of Jesus is called to make with humility and patience, with generosity and perseverance.

Following the divine Teacher in docility makes Christians witnesses and apostles of peace. We might say that this inner attitude also helps us to highlight more clearly what response Christians should give to the violence that is threatening peace in the world.

It should certainly not be revenge, nor hatred nor even flight into a false spiritualism. The response of those who follow Christ is rather to take the path chosen by the One who, in the face of the evils of his time and of all times, embraced the Cross with determination, following the longer but more effective path of love.

Following in his footsteps and united to him, we must all strive to oppose evil with good, falsehood with truth and hatred with love.

In the Encyclical Deus Caritas Est, I wanted to present this love as the secret of our personal and ecclesial conversion. Referring to Paul’s words to the Corinthians, “the love of Christ urges us on” (II Cor 5: 14), I stressed that “the consciousness that, in Christ, God has given himself for us, even unto death, must inspire us to live no longer for ourselves but for him, and, with him, for others” (n. 33).

[Pope Benedict, homily 1 March 2006]

Fighting personal sin and "sin structures”

1. As we continue our reflection on conversion, sustained by the certainty of the Father's love, today we will focus our attention on the meaning of sin, both personal and social.

Let us first look at Jesus' attitude, since he came to deliver mankind from sin and from Satan's influence.

The New Testament strongly emphasizes Jesus' authority over demons, which he cast out "by the finger of God" (Lk 11: 20). In the Gospel perspective, the deliverance of those possessed by demons (cf. Mk 5: 1-20) acquires a broader meaning than mere physical healing in that the physical ailment is seen in relation to an interior one. The disease from which Jesus sets people free is primarily that of sin. Jesus himself explains this when he heals the paralytic: ""That you may know that the Son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins' he said to the paralytic "I say to you, rise, take up your pallet and go home'" (Mk 2: 10-11). Even before working cures, Jesus had already conquered sin by overcoming the "temptations" which the devil presented to him during the time he spent in the wilderness after being baptized by John (cf. Mk 1: 12-13); Mt 4: 1-11; Lk 4: 1-13).

To fight the sin that lurks in us and around us, we must follow in Jesus' footsteps and learn the sense of his constant "yes" to the Father's plan of love. This "yes" demands our total commitment, but we would not be able to say it without the help of that grace which Jesus himself obtained for us by his work of redemption.

2. Now, looking at the world today we have to admit that there is a marked decline in the consciousness of sin. Because of widespread religious indifference or the rejection of all that right reason and Revelation tell us about God, many men and women lack a sense of God's Covenant and of his commandments. All too often the human sense of responsibility is blurred by a claim to absolute freedom, which it considers threatened and compromised by God, the supreme legislator.

The current tragic situation, which seems to have foresaken certain fundamental moral values, is largely due to the loss of the sense of sin. This fact makes us aware of the great distance to be covered by the new evangelization. Consciences must recover the sense of God, of his mercy, of the gratuitousness of his gifts to be able to recognize the gravity of sin which sets man against his Creator. Personal freedom should be recognized and defended as a precious gift of God, resisting the tendency to lose it in the structures of social conditioning or to remove it from its inalienable reference to the Creator.

3. It is also true that personal sin always has a social impact. While he offends God and harms himself, the sinner also becomes responsible for the bad example and negative influences linked to his behaviour. Even when the sin is interior, it still causes a worsening of the human condition and diminishes that contribution which every person is called to make to the spiritual progress of the human community.

In addition to all this, the sins of individuals strengthen those forms of social sin which are actually the fruit of an accumulation of many personal sins. Obviously the real responsibility lies with individuals, given that the social structure as such is not the subject of moral acts. As the Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia recalls: "Whenever the Church speaks of situations of sin, or when she condemns as social sins certain situations or the collective behaviour of certain social groups, big or small, or even of whole nations and blocs of nations, she knows and she proclaims that such cases of social sin are the result of the accumulation and concentration of many personal sins.... The real responsibility, then, lies with individuals" (n. 16).

It is nevertheless an indisputable fact, as I have often pointed out, that the interdependence of social, economic and political systems creates multiple structures of sin in today's world. (cf. Sollicitudo rei socialis, n. 36; Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1869). Evil exerts a frightening power of attraction which causes many types of behaviour to be judged "normal" and "inevitable". Evil then grows, having devastating effects on consciences, which become confused and even incapable of discernment. If one then thinks of the structures of sin that hinder the development of the peoples most disadvantaged from the economic and political standpoint (cf. Sollicitudo rei socialis, n. 37), one might almost surrender in the face of a moral evil which seems inevitable. So many people feel powerless and bewildered before an overwhelming situation from which there seems no escape. But the proclamation of Christ's victory over evil gives us the certainty that even the strongest structures of evil can be overcome and replaced by "structures of good" (cf. ibid., n. 39).

4. The "new evangelization" faces this challenge. It must work to ensure that people recover the awareness that in Christ evil can be conquered with good. People must be taught a sense of personal responsibility, closely connected with moral obligations and the consciousness of sin. The path of conversion entails the exclusion of all connivance with those structures of sin which, today in particular, influence people in life's various contexts.

The Jubilee offers individuals and communities a providential opportunity to walk in this direction by promoting an authentic "metanoia", that is, a change of mentality that will help create ever more just and human structures for the benefit of the common good.

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 25 August 1999]

Letting oneself slip slowly into sin, relativising things and entering "into negotiation" with the gods of money, vanity and pride: from what he called a "fall with anaesthesia" the Pope warned in the homily of the Mass celebrated at Casa Santa Marta on Thursday morning, 13 February, reflecting on the story of King Solomon.

The first reading of the day's liturgy (1 Kings 11:4-13) "tells us," he began, "the apostasy, let us say, of Solomon," who was not faithful to the Lord. In fact, when he was old, his women made him "turn aside his heart" to follow other gods. He was first a 'good boy', who asked the Lord only for wisdom, and God made him wise, to the point that judges and even the Queen of Sheba, from Africa, came to him with gifts because she had heard of his wisdom. "You can see that this woman was a bit of a philosopher and asked him difficult questions," the Pontiff said, noting that "Solomon came out of these questions victorious" because he knew how to answer them.

At that time, Francis continued, one could have more than one bride, which did not mean, he explained, that it was licit to be a 'womanizer'. Solomon's heart, however, was weakened not because he had married these women - he could do so - but because he had chosen them from another people, with other gods. And Solomon therefore fell into the "trap" and allowed it when one of his wives asked him to go and worship Camos or Moloc. And so he did for all his foreign women who offered sacrifices to their gods. In a word, 'he allowed everything, he stopped worshipping the one God'. From a heart weakened by too much affection for women, 'paganism entered his life'. Therefore, Francis pointed out, that wise boy who had prayed well asking for wisdom, fell to the point of being rejected by the Lord.

"It was not an overnight apostasy, it was a slow apostasy," the Pope clarified. King David, his father, had also sinned - strongly at least twice - but immediately repented and asked for forgiveness: he had remained faithful to the Lord who kept him until the end. David wept for that sin and for the death of his son Absalom, and when he fled from him before, he humbled himself thinking of his sin, when people insulted him. "He was holy. Solomon is not holy," said the Pontiff. The Lord had given him so many gifts but he had wasted it all because he had let his heart be weakened. It is not a matter, he noted, of the 'one-time sin' but of 'slipping'.

"The women led his heart astray and the Lord rebuked him: 'You have led your heart astray'. And this happens in our lives. None of us are criminals, none of us do great sins as David did with Uriah's wife, none of us. But where is the danger? Letting yourself slip slowly because it is a fall with anaesthesia, you don't realise it, but slowly you slip, you relativise things and you lose fidelity to God," Francis remarked. "These women were from other peoples, they had other gods, and how often we forget the Lord and enter into negotiation with other gods: money, vanity, pride. But this is done slowly and if there is no grace from God, we lose everything,' he warned again.

Again the Pope recalled Psalm 105 (106) to emphasise that this mixing with the pagans and learning to act like them, means becoming worldly. "And for us this slow slide in life is towards worldliness, this is the grave sin: "Everyone does it, but yes, there is no problem, yes, really it is not the ideal, but...". These words justify us at the price of losing our allegiance to the one God. They are modern idols," Francis warned, asking us to think about "this sin of worldliness" that leads to "losing the genuine of the Gospel. The genuine of the Word of God" to "losing the love of this God who gave his life for us. You cannot be right with God and right with the devil. We all say this when we talk about a person who is a bit like this: 'This one is well with God and with the devil. He has lost faithfulness'.

And, in practice, the Pontiff continued, this means not being faithful 'neither to God nor to the devil'. Therefore, in conclusion, the Pope urged to ask the Lord for the grace to stop when one realises that the heart begins to slip. "Let us think of this sin of Solomon," he recommended, "let us think of how that wise Solomon fell, blessed by the Lord, with all the inheritances of his father David, how he fell slowly, anaesthetised towards this idolatry, towards this worldliness, and his kingdom was taken away from him.

And "let us ask the Lord," Francis concluded, "for the grace to understand when our heart begins to weaken and slip, to stop. It will be his grace and his love that will stop us if we pray to him."

[Pope Francis, St. Martha, in L'Osservatore Romano 14/02/2020]

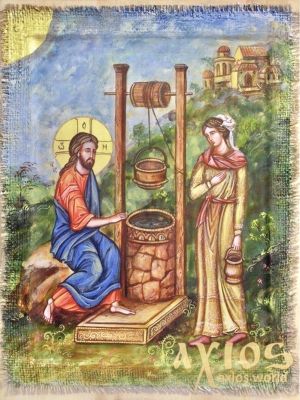

Third Lent Sunday (year A) [8 March 2026]

May God bless us and the Virgin Mary protect us! Have a good Lenten journey as we pause today with Jesus at the well, a place of life-changing encounters.

*First Reading from the Book of Exodus (17:3-7)

Looking at a map of the Sinai desert, Massa and Meriba are nowhere to be found: they are not specific geographical locations, but symbolic names. Massa means 'challenge', Meriba means 'accusation'. These names recall an episode of challenge, of protest, almost of mutiny against God. The episode takes place in Rephidim, in the middle of the desert, between Egypt and the Promised Land. The people of Israel, led by Moses, advanced from stage to stage, from one water source to another. But at Rephidim, the water ran out. In the desert, under the scorching sun, thirst quickly becomes a matter of life and death: fear grows, panic takes over. The only right response would have been trust: 'God wanted us to be free, he proved it, so he will not abandon us'. Instead, the people give in to fear and react as we often react ourselves: they look for someone to blame. And the culprit seems to be Moses, the 'government' of the time. What is the point, they say, of leaving Egypt only to die of thirst in the desert? Better to be slaves but alive than free but dead. And, as always happens, the past is idealised: they remember the full pots and abundant water of Egypt, forgetting the slavery. In reality, behind the accusation against Moses, there is a deeper accusation: against God himself. What kind of God is this, they ask themselves, who frees a people only to let them die in the desert? The protest: Why did you bring us out of Egypt? To let us, our children and our livestock die of thirst? It becomes increasingly harsh, until it turns into a real trial against God: as if God had freed the people only to get rid of them. Moses then cries out to the Lord: What shall I do with this people? A little more and they will stone me!

And God replies: he orders him to take the staff with which he had struck the Nile, to go to Mount Horeb and to strike the rock. Water gushes forth, the people drink, and their lives are saved (cf. Exodus 17). That water is not only physical relief: it is a sign that God is truly present among his people, that he has not abandoned them and that he continues to guide them on the path to freedom. For this reason, that place will no longer be called simply Rephidim, but Massah and Meribah, 'Testing and Accusation', because there Israel tested God, asking themselves: Is the Lord among us or not? In modern language: 'Is God for us or against us?' This temptation is also ours. Every trial, every suffering, reopens the same original question: can we really trust God? It is the same temptation recounted in the Garden of Eden (Genesis): the suspicion that God does not really want our good poisons human life. This is why Jesus Christ, teaching the Our Father, educates his disciples in filial trust. Do not abandon us to temptation could be translated as: "Do not let our Refidim become Massa, do not let our places of trial become places of doubt." Continuing to call God "Father," even in difficult times, means proclaiming that God is always with us, even when water seems to be lacking.

*Responsorial Psalm (94/95),

In the Bible, the original text of the psalm reads as follows: "Today, if you hear his voice,

do not harden your hearts as at Massah and Meribah, as on the day of Massah in the desert, where your fathers tested me even though they had seen my works." This psalm is deeply marked by the experience of Massah and Meribah. This is why the liturgy proposes it on the third Sunday of Lent, in harmony with the story of the Exodus: it is a direct reference to the great question of trust. In a few lines, the psalm summarises the whole adventure of faith, both personal and communal. The question is always the same: can we trust God?

For Israel in the desert, this question arose at every difficulty: ' Is the Lord really among us or not?' In other words: can we rely on Him? Will He really support us? Faith, in the Bible, is first and foremost trust. It is not an abstract idea, but the act of 'relying' on God. It is no coincidence that the word 'Amen' means 'solid', 'stable': it means 'I trust, I have faith' . This is why the Bible insists so much on the verb 'to listen': when you trust, you listen. It is the heart of Israel's prayer, the Shema Israel: Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God... You shall love Him, that is, you shall trust Him. 'To listen' means to have an open ear. The psalm says: 'You have opened my ear' (Ps 40), and the prophet Isaiah writes: The Lord God has opened my ear. Even 'obeying' in the Bible means this: listening with trust. This trust is based on experience. Israel has seen the 'work of God': liberation from Egypt. If God has broken the chains of slavery, He cannot want His people to die in the desert. This is why Israel calls him 'the Rock': it is not poetry, it is a profession of faith. At Massah and Meribah, the people doubted, but God brought water out of the rock: since then, God has been the Rock of Israel. Even the story of the Garden of Eden (Genesis) can be understood in the light of this experience: every limitation, every command, every trial can become a question of trust. Faith is believing that, even when we do not understand, God wants us to be free, alive and happy, and that from our situations of failure he can bring forth new life. Sometimes this trust resembles a 'leap of faith' when we cannot find answers. Then we can say with Simon Peter in Capernaum: 'Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life'. When Paul of Tarsus writes: ' Be reconciled to God', it is like saying: stop suspecting God, as at Massah and Meribah. And when the Gospel of Mark says, 'Repent and believe in the Gospel', it means: believe that the Good News is truly good, that God loves you. Finally, the psalm says, 'Today'. It is a liberating word: every day can be a new beginning. Every day we can relearn to listen and to trust. This is why Psalm 94/95 opens the Liturgy of the Hours every morning and Israel recites the Shema twice a day. And the psalm speaks in the plural: faith is always a journey of a people. 'We are the people He guides'. This is not poetry: it is experience. The Bible knows a people who, together, come to meet their God: "Come, let us acclaim the Lord, let us acclaim the rock of our salvation." It is faith that comes from trust, renewed today, day after day.

*Second Reading from the Letter of St Paul to the Romans (5:1-2, 5-8)

Chapter 5 of the Letter to the Romans marks a decisive turning point. Up to this point, Paul of Tarsus had spoken of humanity's past, of pagans and believers; now he looks to the future, a future transfigured for those who believe, thanks to the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. To understand Paul's thinking clearly, we can summarise it in three fundamental statements. 1. Christ died for us while we were sinners. Paul affirms that Christ died 'for us'. This expression does not mean 'in our place', as if Jesus had simply replaced those who were condemned, but 'on our behalf'. When humanity was incapable of saving itself, marked by violence, injustice, greed for power and money, Christ took this reality upon himself and fought it to the point of giving his life.

Humanity, created for love, peace and sharing, had lost its way. Jesus comes to say, with his life and death: "I will show you to the very end what it means to love and forgive. Follow me, even if it costs me my life."

2. The Holy Spirit has been given to us: God's love dwells in us. The second great affirmation is this: the Holy Spirit has been given to us, and with him, God's own love has been poured into our hearts. It is no coincidence that Paul speaks of the Spirit for the first time when he speaks of the cross. For him, passion, cross and gift of the Spirit are inseparable. Here Paul is in complete harmony with the evangelist John. In his Gospel, during the Feast of Tabernacles, Jesus promises "living water," explaining that he was speaking of the Spirit (cf. Gospel of John (7:37-39). And at the moment of the cross, John writes: Bowing his head, Jesus gave up his spirit (Jn 19:30). The promise is fulfilled: from the cross comes the gift of the Spirit. 3. Our 'boast' is the hope of God's glory. Paul also speaks of 'pride', but he makes it clear: we cannot boast about ourselves, because everything is a gift from God; but we can boast about God's gifts, about the wonderful destiny to which we are called. The Spirit already dwells in us, and we know that one day this same Spirit will transform our bodies and hearts into the image of the risen Christ.

The account of the Transfiguration has given us a foretaste of this glory.

From Massah and Meribah to glory. What an immense journey compared to Massah and Meribah, where the people doubted God! Now, thanks to our faith in Christ, we can say with Paul: "Through him we also have access by faith into this grace in which we stand, and we rejoice in hope of the glory of God" (5:2). In conclusion, the Spirit that Jesus has given us is the very love of God. This certainty should overcome all fear. If God's love has been poured into our hearts, then the forces of division will not have the last word.

For believers, and for all humanity, hope is well-founded, because "the love of God has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us" (5:5).

*From the Gospel according to John (4:5-42)

Jesus meets us today at the well. And this detail is not secondary. In the Bible, the well is never just a place where water is drawn: it is a place of decisive encounters, where life changes direction. At a well, Abraham's servant meets Rebecca, who will become Isaac's wife; at a well, Jacob falls in love with Rachel. At the well, relationships, alliances and the future are born. When John places Jesus at a well, he is telling us that something decisive is about to happen. Jesus arrives at Jacob's well in Samaria. It is midday. Jesus is tired and sits down. The Gospel immediately shows us a God who stops, who accepts fatigue, who enters our life as it is. Salvation begins with a pause, not with a spectacular gesture. At that hour, a woman arrives. She is alone. Jesus says to her, 'Give me a drink'. It is a surprising request. Jesus, a Jew, speaks to a Samaritan woman; a man speaks to a woman; a righteous man speaks to a person whose life has been wounded. God does not enter our lives by imposing himself, but by asking. He becomes a beggar for our hearts. From that simple request, a dialogue arises that goes ever deeper. Jesus leads the woman from the external well to her inner thirst: "If you knew the gift of God..." The water that Jesus promises is not water to be drawn every day, but a spring that gushes within, a life that does not run dry. It does not eliminate daily life, but transfigures it from within. Then Jesus touches on the truth of the woman's life. He does not judge her, he does not humiliate her. In the Gospel, truth does not serve to crush, but to liberate. Only those who accept to be known can receive the gift. The woman then asks a religious question: where should God be worshipped? On the mountain or in the temple? Jesus responds by shifting the focus: no longer where, but how. 'In Spirit and truth'. God is no longer encountered in one place as opposed to another, but in a living relationship. The true temple is the heart that allows itself to be inhabited. When the woman speaks of the Messiah, Jesus makes one of the most powerful revelations in the entire Gospel: 'I am he, the one who is speaking to you'. The Messiah does not manifest himself in the temple, but in a personal dialogue, at a well, to a woman considered unclean. As in the ancient stories of wells, here too the encounter opens up a promise: but now the Bridegroom is Jesus Christ and the covenant is new. The woman leaves her jug behind. It is a simple but decisive gesture. The jug represents old certainties, repeated attempts to quench a thirst that never goes away. Those who have encountered Christ no longer live to draw water, but to bear witness. The woman runs into town and says, 'Come and see'. She does not give a lesson, she recounts an encounter. And many believe, to the point of saying, 'Now we no longer believe because of what you said, but because we ourselves have heard'. Today's Gospel tells us this: Christ does not take us away from the well of life, but transforms the well into a place of salvation. Our thirst becomes an encounter, the encounter becomes a gift, the gift becomes a source for others. This is Lent: allowing ourselves to be encountered by Christ and becoming, in turn, living water for those who are thirsty.

+Giovanni D'Ercole

(Mt 5:17-19)

In the face of the Law’s precepts, distant attitudes appear.

There are those who demonstrate attachment to the material sense of what has been established. Others, omission or contempt for the rules.

Jesus offered such a new and radical teaching as to give the impression of carelessness and rejection of the Law. But in fact, more than his differences with it, He was attentive to the profound meaning of the biblical-Jewish directives.

He didn’t intend to «demolish» (v.17) the Torah, but he certainly avoided allowing himself to be minimized in the cases of morality that parceled out the basic choices - and made them all exterior, without fulcrum.

The legalistic sclerotization easily tended to equate the codes... with God. But for the believer, his "obligation" is at the same time Event, Word, and Person: global following.

In the first communities some faithful believed that the norms of the First Testament should no longer be considered, as we are saved by Faith, not by works of Law.

Others accepted Jesus as the Messiah, but couldn’t bear the excess of freedom with which some brothers of the church lived his Presence.

Still linked to an ideal ethnic background, they believed that ancient observance was mandatory.

There was no lack of brothers enraptured by an excess of fantasies in the Spirit. In fact, some denied the Hebrew Scriptures and considered themselves free from history: they no longer looked at the life of Jesus.

Mt seeks a balance between emancipation and closure.

He writes his Gospel to support converts to the Faith in Christ in the communities of Galilee and Syria, accused by the Judaizers of being unfaithful to the Torah.

The evangelist clarifies that Jesus himself had been accused of serious transgressions to the Law of Moses.

The trajectory of the Jewish Scriptures is the right one, but it doesn’t have an unanimous and totally clear starting point, nor the strength in itself to reach Target.

The arrow of the Torah has been shot in the right direction, but only in the Spirit of the Beatitudes can a living assembly gain momentum to reach Communion.

The Gospel passage is concerned to emphasise: the ancient Scriptures, the historical story of Jesus, and life in the Spirit must be evaluated inseparable aspects of a single plan of salvation.

Lived in synergy, they lead to the conviviality of differences.

The God of the patriarchs makes himself present in the loving relationship of the communities, through faith in Christ, who expands his own life in their hearts.

The Living One conveys the Spirit that spurs all creativity, He overcomes unfriendly closures; He opens, and invites.

[In us, Jesus of Nazareth becomes a living Body - and the pleasure of doing manifests Him (from the soul) in Person and full Fidelity].

Handing oneself out to brothers and going to God thus becomes agile, spontaneous, rich and very personal for everyone: the Strength comes from within.

New or ancient Words, and Spirit renewing the face of the earth, are part of one Plan.

Only in the total fascination of the Risen One does our harvest come to complete life - the full objective of the Law - becoming ‘forever’.

[Wednesday 3rd wk. in Lent, March 11, 2026]

Doing a good deed almost instinctively gives rise to the desire to be esteemed and admired for the good action, in other words to gain a reward. And on the one hand this closes us in on ourselves and on the other, it brings us out of ourselves because we live oriented to what others think of us or admire in us (Pope Benedict)

Quando si compie qualcosa di buono, quasi istintivamente nasce il desiderio di essere stimati e ammirati per la buona azione, di avere cioè una soddisfazione. E questo, da una parte rinchiude in se stessi, dall’altra porta fuori da se stessi, perché si vive proiettati verso quello che gli altri pensano di noi e ammirano in noi (Papa Benedetto)

Since God has first loved us (cf. 1 Jn 4:10), love is now no longer a mere “command”; it is the response to the gift of love with which God draws near to us [Pope Benedict]

Siccome Dio ci ha amati per primo (cfr 1 Gv 4, 10), l'amore adesso non è più solo un « comandamento », ma è la risposta al dono dell'amore, col quale Dio ci viene incontro [Papa Benedetto]

Another aspect of Lenten spirituality is what we could describe as "combative" […] where the "weapons" of penance and the "battle" against evil are mentioned. Every day, but particularly in Lent, Christians must face a struggle […] (Pope Benedict)

Un altro aspetto della spiritualità quaresimale è quello che potremmo definire "agonistico" […] là dove si parla di "armi" della penitenza e di "combattimento" contro lo spirito del male. Ogni giorno, ma particolarmente in Quaresima, il cristiano deve affrontare una lotta […] (Papa Benedetto)

Jesus wants to help his listeners take the right approach to the prescriptions of the Commandments given to Moses, urging them to be open to God who teaches us true freedom and responsibility through the Law. It is a matter of living it as an instrument of freedom (Pope Francis)

Gesù vuole aiutare i suoi ascoltatori ad avere un approccio giusto alle prescrizioni dei Comandamenti dati a Mosè, esortando ad essere disponibili a Dio che ci educa alla vera libertà e responsabilità mediante la Legge. Si tratta di viverla come uno strumento di libertà (Papa Francesco)

In the divine attitude justice is pervaded with mercy, whereas the human attitude is limited to justice. Jesus exhorts us to open ourselves with courage to the strength of forgiveness, because in life not everything can be resolved with justice. We know this (Pope Francis)

Nell’atteggiamento divino la giustizia è pervasa dalla misericordia, mentre l’atteggiamento umano si limita alla giustizia. Gesù ci esorta ad aprirci con coraggio alla forza del perdono, perché nella vita non tutto si risolve con la giustizia; lo sappiamo (Papa Francesco)

The true prophet does not obey others as he does God, and puts himself at the service of the truth, ready to pay in person. It is true that Jesus was a prophet of love, but love has a truth of its own. Indeed, love and truth are two names of the same reality, two names of God (Pope Benedict)

Il vero profeta non obbedisce ad altri che a Dio e si mette al servizio della verità, pronto a pagare di persona. E’ vero che Gesù è il profeta dell’amore, ma l’amore ha la sua verità. Anzi, amore e verità sono due nomi della stessa realtà, due nomi di Dio (Papa Benedetto)

“Give me a drink” (v. 7). Breaking every barrier, he begins a dialogue in which he reveals to the woman the mystery of living water, that is, of the Holy Spirit, God’s gift [Pope Francis]

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.