XX Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C) [17 August 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. Here is the commentary on next Sunday's biblical texts.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Jeremiah (38:4-6, 8-10)

The name Jeremiah gave rise to the term 'jeremiad'. But it would be a mistake to think that this prophet spent his time complaining and feeling sorry for himself. It is true, however, that he was often led to cry out for mercy under the weight of his trials. And God knows how many he experienced! So much so that the proverb 'No one is a prophet in his own country' applies particularly to him. At times, expressions of utter discouragement emerge from his pen (cf. Jer 15:10, 18; 20:14). Faced with the repeated failures of his mission and the evils of which he is a victim, Jeremiah asks himself disturbing questions, even going so far as to call God to account, whose conduct seems surprising, if not downright unjust: "You are righteous, Lord! But I want to argue with you. Why do the wicked prosper? Why are all the treacherous at ease?" (Jer 12:1-2). Reading the book of Jeremiah, we realise that he had good reasons to ask these questions and complain: chapter after chapter, the plots of his adversaries emerge, along with their deceit and threats, which are then cruelly carried out (cf. Jer 20:10; 18:18; 11:21; 12:6). In the passage proposed by the liturgy this Sunday, we are faced with one of his many misfortunes, a typical episode of his life in which all the arguments and wickedness of his adversaries appear: "Kill Jeremiah, for he is discouraging the warriors who are left in this city and discouraging the people by speaking to them like this, for this man is not seeking the welfare of the people, but their harm" (v. 4). They took him and threw him into the cistern of Prince Melchiah, where there was no water but mud, and he sank into the mud, so that the persecution he suffered could not be described more realistically. However, God did not abandon his prophet, but kept the promise he made on the day of his calling, to sustain him against all adversity, and it was truly a covenant between God and him (Jer 1:4-5, 17-19); in fact, on a day when he was particularly discouraged, God renewed his mission and his promise (Jer 15:21), and now the instrument of liberation will be a foreigner, an Ethiopian named Ebed-Melech. This is not the first time that the Bible presents us with foreigners who are more respectful of God and his prophets than the chosen people. This Ethiopian has the courage to intervene with the king, who grants permission to save Jeremiah. When Jesus later tells the parable of the Good Samaritan, he may have been thinking of this Ethiopian who saved the prophet, because there are many similarities between the Good Samaritan and the Ethiopian. In the rest of the story, verses not included in the liturgical text, many details emerge about the sensitivity of the pagan who saves the prophet, taking every precaution not to hurt him during the ascent (28:11-13). Why is no one a prophet in his own country? This is a recurring question: it probably happens because the proclamation of God's love for humanity requires us to love one another, and when we live together, it is easier to see the negative than the positive: 'No one is great in the eyes of his neighbour'. Job's complaints (in chapter 3) are similar to those of Jeremiah, and it is thought that the author of the Book of Job was inspired by the lamentations of Jeremiah, considered the quintessential example of the persecuted righteous man.

Responsorial Psalm (39/40:2,3,4,18)

"I waited patiently for the Lord, and he turned to me." The psalm speaks in the first person singular, but in reality it is the people of Israel who sing their gratitude because they have gone through terrible trials and God has delivered them. This psalm is therefore a psalm of thanksgiving, composed to be sung in the Temple at the time of the offering of a sacrifice of thanksgiving, animal sacrifices celebrated until the final destruction of the Temple in 70 AD. The whole people bursts with joy on their return from Babylonian exile, as after the crossing of the Red Sea. Exile was like a deadly fall into a bottomless pit, an abyss from which it seemed impossible to rise, and the psalm speaks of the 'terror of the abyss'. During that long period of trial, the people, supported by priests and prophets, maintained their hope and strength to call for help: 'You are my help and my deliverer: my God, do not delay! (v. 18) and God saved them: 'The Lord... has heard my cry' (v. 2). On their return, the people seem resurrected and give thanks: 'He has put a new song in my mouth... Many will see and fear and trust in the Lord... But I am poor and needy: the Lord cares for me" (vv. 4, 18). Before the exile, Israel lived in security, but the prophets had failed to awaken it from its indifference. During the exile, it meditated on the causes of the disaster, wondering if the cause was not its own superficiality. This psalm sounds like a warning for the future, or rather a resolution because, in order not to fall back into the same error, Israel must live faithfully according to the Covenant. In this spirit, the psalm develops a reflection on what truly pleases God: "You do not desire sacrifices or offerings... You have not asked for burnt offerings or sacrifices for sin. Then I said, 'Here I am, I come'. (vv. 7, 8, 9). To express the experience of returning to the promised land as a return to life, the psalmist uses the parable of a man thrown into a pit by his enemies, perhaps inspired by the experience of the prophet Jeremiah, whose misadventures are recounted in the first reading: thrown into a pit, he is freed by Ebed-Melek, a foreigner. Jeremiah knew that behind that man's surprising generosity was God himself: "He has brought me up out of a pit of destruction, out of the miry bog, and set my feet upon a rock and established my goings" (v. 3). Freed, he bursts with joy: "He has put a new song in my mouth, a hymn of praise to our God. Many will see and trust in the Lord" (v. 4). Those who have been saved sing God's praise, and others, seeing that God saves, will want to turn to Him. The psalm does not stop there, because the final verse proclaims: "You are my help and my deliverer: my God, do not delay!" (v. 18). Since humanity has not yet reached the full fulfilment of God's plan, the psalmist suggests two attitudes of prayer: praise for the salvation that has already taken place, so that others may open themselves to the saving God; supplication for the salvation we still await, so that the Spirit may inspire us to take the necessary action. It is not we who save the world, as the psalm says: "He has put a new song in my mouth, a hymn of praise to our God. Many will see and trust in the Lord" (v. 4). God will always find a small remnant to save. Amos says: "The God of hosts will have mercy on the remnant of Joseph" (5:15); Isaiah also repeats similar things, which are then elaborated on by Micah, Zephaniah and Zechariah, who announce that the "remnant" of Israel will not only be saved, but will become an instrument of salvation for all others. God will use them to save all humanity, as Micah says: "The remnant of Jacob will be, among many peoples, like dew from the Lord" (5:6).

Second Reading from the Letter to the Hebrews (12:1-4)

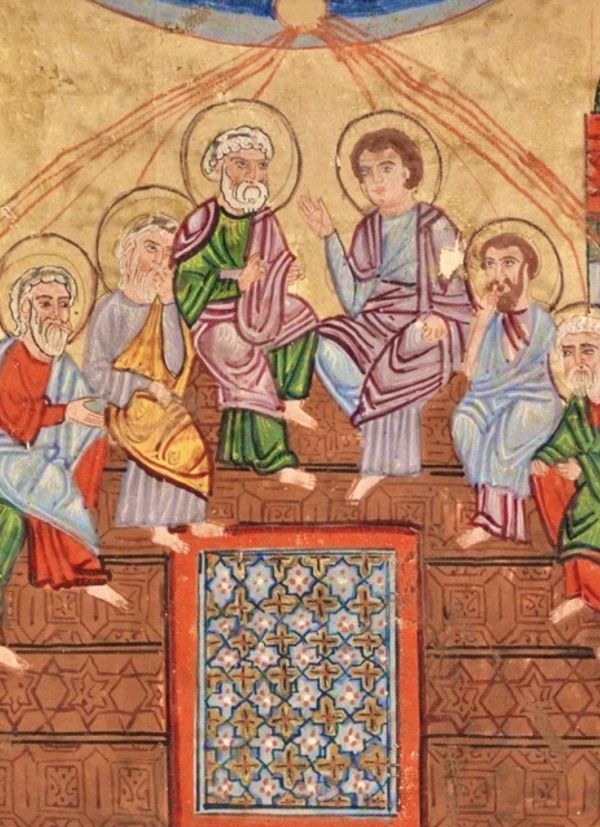

The author of the Letter addresses words of encouragement to persecuted Christians. He devoted chapter 11 to presenting the great models of faith in the Old Testament, and last Sunday we spoke about Abraham and Sarah. Here, at the beginning of chapter 12, he states that all believers in the Old Testament are like a "cloud of witnesses" surrounding us: a cloud of protectors. The author is not content with recommending that Christians imitate the trust and constancy of the great figures of the past, but invites them to "keep their eyes fixed on Jesus," the ever-present witness, the one who said, "I am with you always, until the end of the age" (Mt 28:20), the origin of faith and its fulfilment. A more literal translation would be: Jesus is the 'pioneer of faith', and the Greek term used, ἀρχηγός archēgós, translated as 'pioneer', indicates leader, commander, pioneer, initiator, founder, the one who opens the way and leads forward, a perfect guide who can be trusted because he leads to full fulfilment. In fact, he himself underwent the test of perseverance, in which Christians are now also engaged. His test was much harder: coming as the Bridegroom, for the joy of a wedding feast, he had said of himself that one cannot make the guests fast while the bridegroom is with them (cf. Mk 2:19), but the Bridegroom was not recognised and, renouncing the joy that was set before him, he endured the cross, despising the shame of that punishment. St. Paul says it in another way when he writes to the Philippians: "Though he was in the form of God, he did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave... he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross" (Phil 2:6-8). Such a contrast is unimaginable: having come to save humanity from sin, Christ was dramatically rejected and killed because of the sins of men: "Consider carefully the one who has endured such hostility from sinners" (v. 3). Both the Letter to the Hebrews and the Letter to the Philippians emphasise that Jesus is our model and support not because of the quantity of his sufferings, but because of his "obedience" unto death, even death on a cross, as Paul writes, while in the Letter to the Hebrews we read that although he was a Son, he learned obedience from the things he suffered (cf. 5:8). To obey – from the Latin ob-audire – literally means 'to place one's ear before the Word', which is the attitude of absolute trust. Jesus, in the most extreme situation, maintains total trust in the Father, who is always present and attentive to his beloved Son, sharing his suffering and anguish: 'He remains faithful, because he cannot deny himself' (2 Tim 2:13). This is followed by the triumph of God's love, and Christ sits at the right hand of God, reigning with him. This same triumph is promised to those who endure persecution like Christ. The author does not hesitate to use the word "struggle" to describe this courage: the Christians to whom he writes visibly risk their lives to remain faithful to Jesus, who had warned them: "You will be betrayed even by parents, brothers, relatives and friends, and they will put some of you to death... But by your perseverance you will save your lives" (Lk 21:12-19). Throughout the world, some Christians are directly affected by this fate because they are experiencing open or hidden persecution. We, who at least for the moment do not know direct persecution, are asked to be witnesses by speaking courageously about God and defending his truth.

From the Gospel according to Luke (12:49-53)

Jesus compares his mission to a fire: "I have come to set the earth on fire, and how I wish it were already burning!" From the fire of Pentecost, this proclamation spread like a flame: among the Jewish people it appeared as the destroyer of the entire religious edifice, in the pagan world it was considered a contagious madness. St Paul writes to the Corinthians: "We preach a crucified Messiah, a scandal to Jews and foolishness to pagans." (1 Cor 1:23). This fire leaves indelible traces: those who allow themselves to be burned by the Gospel and those who reject it become irreconcilable enemies, even if they are united by family ties, thus fulfilling what the prophet Micah described with desolation in his time of anguish: "The son insults his father, the daughter rebels against her mother, the daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; each person's enemies are their own family members." (Mi 7:6). When Jesus announces these divisions, it is not a mere premonition: he speaks from experience, as happened in Nazareth where, after an initial enthusiasm, his childhood friends and family turned against him because he had just said that his mission went beyond the borders of Israel (Lk 4:28-29). And this is not the only time that Jesus encounters misunderstanding, even opposition from his own people: St John writes that not even his brothers believed in him (cf. Jn 7:5). Moreover, Jesus does not hesitate to tell his disciples that one of the conditions for proclaiming the Kingdom of God is to accept possible painful separations. For if one wants to follow him but does not love him more than one's dearest ones and even more than one's own life, one will never become his disciple (cf. Lk 14:26). The fire he has kindled leads to radical choices. Israel was waiting for a Messiah who would bring peace to the world, as the prophecies of Isaiah (Isaiah 2:11) were well known, but Jesus instead announces divisions: "Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but division." Jesus' peace requires a radical conversion of the heart, but many will oppose this conversion with all their strength. His proclamation of peace will meet with the favour of some, but the opposition of many: having come among us to proclaim love and salvation, he suffered and died, as he himself had foretold: "The Son of Man must suffer greatly, be rejected by the elders, the chief priests and the scribes, be killed and rise on the third day." (Lk 9:22). And again: he will be handed over to the pagans, mocked, insulted, spat upon, scourged and killed, but he will rise on the third day (cf. Lk 18:32). His resurrection gives us courage: enlivened by his Spirit poured out upon us, we are not afraid to set the world on fire with the fire of his charity.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole