don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Without annulling the person, already bare of two cents

Pennies and festivals of the voracious God, in solemn appearances

(Lk 21:1-4)

Jesus conveys the Glad Tidings that the Father is the exact opposite of what was imagined.

He does not take, or appropriate, or absorb, or debase, but it is He who gives; He does not chastise unless you appease Him with both coins you have, without withholding even one (v.2).

Honour to God is not exclusive, but inclusive.

Paraphrasing the encyclical Fratelli Tutti, we could say that in authentic communities [as in families] "all contribute to the common project, all work for the common good, but without annulling the individual; on the contrary, they support him, they promote him" (n.230).

In particular, the rich-poor antithesis is heralded by the reversal of lifestyle, situations and destinies: characteristic of the ideal Church, which remains a pilgrim - even in the space of the Person.

Its good reason, virtuous practices and public implications are immersed in the same rhythm as the supreme Life Source - which loves uniqueness, for the sake of common wealth.

With the exception of good relations, the institution can appear unattractive. It does not impose itself by force of 'favourable' social conditions, but is Presence on the plane of Faith.

Friendship that contemplates a new world, capable of humanising disharmonies.

Reality that beats time - because it is inside and outside of it, like Love.

It is the soul that counts, not the curriculum; not even conditioning influences, which only make things difficult.

Indeed, the feeling of being poor or late starts with making comparisons - and wanting to add, to anticipate, to demand an external more.

But what counts in the relationship with oneself, with others and with God is only being able to express one's own nature. Making choices in tune with the essence that characterises.

Calculations are deviant, not consonant; so are comparisons. The small fleeting but personal detail is decisive.

It is only important to coincide with what we are, in that present; in synchrony with one's character.

We are what we are. The development will go well.

Jesus confronts the treasure of the Temple, the true 'god' of the whole sanctuary. The confrontation is merciless: one pitted against the other [v.1; cf. Mk 12:41].

An enigma that could not be resolved by a simple "purification" of the sacred place, or a rekindling of devotion.

The Son announces a Father: he is not the one who sucks the resources and energies of creatures, to the point of plucking them out.

The great places of worship of antiquity were veritable banks, the proceeds of which were to provide in part for the needs of the poor.

Fear of divine chastisements inculcated by false spiritual leaders had perverted the situation: even the needy felt they had to provide for the pomp, worship, the decorations of the sacred buildings, and the livelihood of the practitioners of the ritual.

Jesus here does not praise the austerity and humility of an outcast, but looks with sadness at the poor woman who allowed herself to be cheated out of her thoughts, becoming a paradoxical accomplice of the diseducational system.

She could have kept a coin; she throws them both away in vain, and with them "her whole life" (v.4 Greek text).

The original and Jesuit episode is taken up by Lk for a catechesis to his communities, based on events [cf. the ancient writings of James and Paul] under the eyes of second and third generation Christians.

The first fraternities were composed of simple people, but with the entry of the first well-to-do and their magnificent offerings, the same social frictions that were present in the life of the empire began to reappear.

Tensions became more and more evident at both meetings and the breaking of the Bread.

The teaching of the widow's gesture was meant to be a warning to the Royal Communion.

In short, the Kingdom of God is penetration into the depths of life; with dedication that is not reduced to material quantities, nor to handing over what one advances - but what one is.

In the context of the plural society [of the Roman empire and today] from the responsible and motivated Faith arises the elemental Call of the Gospels.

Ancient and current call - for a singular and common experience. Truly non-neutral.

To internalise and live the message:

Who do you consider to be the outstanding characters in your community?

What about your two cents? Do you withhold at least one?

What do you put in the most?

Can people's problems only be solved with a lot of money?

Are the coins of the notable really more useful than your few pennies?

Church, and Light

In the widow who throws her two coins into the treasury in the temple, we can see the "image of the Church" that must be poor, humble and faithful. Pope Francis began from the Gospel of the day, taken from Luke chapter 21 (1-4), his reflection during the Mass at Santa Marta on Monday 24 November. The homily recalls the passage in which Jesus, "after lengthy discussions" with the Sadducees and disciples about the Pharisees and scribes who "take pleasure in having the first places, the first seats in the synagogues, in the banquets, in being greeted", looked up and "saw the widow". The "contrast" is immediate and "strong" compared to the "rich who threw their offerings into the temple treasury". And it is precisely the widow "who is the strongest person here, in this passage".

Of the widow, the Pontiff explained, 'it is said twice that she is poor: twice. And that she is in misery'. It is as if the Lord wanted to emphasise to the doctors of the law: 'You have so many riches of vanity, of appearance, or even of pride. This one is poor. You, who eat widows' houses...". But "in the Bible, the orphan and the widow are the figures of the most marginalised" as well as lepers, and "that is why there are so many commandments to help, to care for widows, for orphans". And Jesus "looks at this woman alone, simply clothed" and "who throws away everything she has to live on: two coins". The thought also runs to another widow, that of Sarepta, "who had received the prophet Elijah and gave everything she had before she died: a little flour with oil...".

The Pontiff recounted the scene narrated by the Gospel: "A poor woman in the midst of the powerful, in the midst of doctors, priests, scribes... also in the midst of the rich who were throwing their offerings, and even some to be seen". To them Jesus says: "This is the way, this is the example. This is the way by which you must go". The "gesture of this woman who was all for God, like the widow Anna who received Jesus in the Temple: all for God. Her hope was only in the Lord".

"The Lord emphasises the person of the widow", Francis said, and continued: "I like to see here, in this woman an image of the Church". First of all the "poor Church, because the Church must have no other riches than her Bridegroom"; then the "humble Church, as the widows of that time were, because at that time there was no pension, no social aid, nothing". In a certain sense the Church 'is a bit of a widow, because she is waiting for her Bridegroom who will return'. Of course, 'she has her Bridegroom in the Eucharist, in the word of God, in the poor: but she waits for him to return'.

And what drives the Pope to "see in this woman the figure of the Church"? The fact that 'she was not important: this widow's name did not appear in the newspapers, nobody knew her, she had no degrees... nothing. Nothing. She did not shine by her own light'. And the 'great virtue of the Church' must be precisely that of 'not shining with her own light', but of reflecting 'the light that comes from her Bridegroom'. All the more so because "over the centuries, when the Church has wanted to have its own light, it has erred". The 'early Fathers' also said so, the Church is 'a mystery like that of the moon. They called it mysterium lunae: the moon has no light of its own; it always receives it from the sun".

Of course, the Pope specified, "it is true that sometimes the Lord may ask his Church to have, to take a little light of its own," as when he asked "the widow Judith to lay down her widow's robes and put on the robes of a feast to go on a mission". But, he reiterated, 'always remains the attitude of the Church towards her Bridegroom, towards the Lord'. The Church 'receives light from there, from the Lord' and 'all the services we do' in it serve to 'receive that light'. When a service lacks this light "it is not good", because "it causes the Church to become either rich, or powerful, or to seek power, or to take the wrong path, as has happened so many times, in history, and as happens in our lives when we want to have another light, which is not the Lord's: a light of our own".

The Gospel, the Pope noted, presents the image of the widow at the very moment when "Jesus begins to feel the resistance of the ruling class of his people: the Sadducees, the Pharisees, the scribes, the doctors of the law. And it is as if he were saying, "All this is happening, but look there!" to that widow. The comparison is fundamental in order to recognise the true reality of the Church that 'when she is faithful to hope and to her Bridegroom, she is joyful to receive light from him, to be - in this sense - a widow: waiting for that sun that will come'.

Moreover, 'it is no coincidence that the first strong confrontation, after the one with Satan, that Jesus had in Nazareth, was for naming a widow and for naming a leper: two outcasts'. There were "many widows in Israel at that time, but only Elijah was sent to that widow of Sarepta. And they became angry and wanted to kill him'.

When the Church, Francis concluded, is 'humble' and 'poor', and also when it 'confesses its miseries - then we all have them - the Church is faithful'. It is as if she were saying: 'I am dark, but the light comes to me!' And this, the Pontiff added, 'does us so much good'. So 'let us pray to this widow who is in heaven, safe', that 'she may teach us to be Church like this', renouncing 'everything we have' and keeping 'nothing for ourselves' but 'everything for the Lord and for our neighbour'. Always "humble" and "without boasting that we have light of our own", but "always seeking the light that comes from the Lord."

[Pope Francis, St. Martha, in L'Osservatore Romano 25/11/2014]

Living stones and Body

At the heart of the Liturgy of the Word […] we find the figure of the poor widow or, more precisely, we find her gesture when she dropped her last coins into the collection box of the Temple treasury. Thanks to Jesus' attentive look it has become the proverbial "widow's mite" and indeed is synonymous with the generosity of those who give unsparingly the little they possess. However, I would like first of all to emphasize the importance of the atmosphere in which this Gospel episode takes place, that is, the Temple of Jerusalem, the religious centre of the People of Israel and the heart of its whole life. The Temple was the place of public and solemn worship, but also of pilgrimage, of the traditional rites and of rabbinical disputations such as those recorded in the Gospel between Jesus and the rabbis of that time in which, however, Jesus teaches with unique authority as the Son of God. He judges the scribes severely as we have heard because of their hypocrisy: indeed, while they display great piety they are exploiting the poor, imposing obligations that they themselves do not observe. Indeed, Jesus shows his affection for the Temple as a house of prayer but for this very reason wishes to cleanse it from improper practices; actually he wants to reveal its deepest meaning which is linked to the fulfilment of his own Mystery, the Mystery of his death and Resurrection, in which he himself becomes the new and definitive Temple, the place where God and man, the Creator and his creature, meet.

The episode of the widow's mite fits into this context and leads us, through Jesus' gaze itself, to focus our attention on a transient but crucial detail: the action of the widow, who is very poor and yet puts two coins into the collection box of the Temple treasury. Jesus is saying to us too, just as he said to his disciples that day: Pay attention! Take note of what this widow has done, because her act contains a great teaching; in fact, it expresses the fundamental characteristic of those who are the "living stones" of this new Temple, namely the total gift of themselves to the Lord and to their neighbour; the widow of the Gospel, and likewise the widow in the Old Testament, gives everything, gives herself, putting herself in God's hands for others. This is the everlasting meaning of the poor widow's offering which Jesus praises; for she has given more than the rich, who offer part of what is superfluous to them, whereas she gave all that she had to live on (cf. Mk 12: 44), hence she gave herself.

Dear friends, starting with this Gospel icon I would like to meditate briefly on the mystery of the Church, the living Temple of God, and thereby pay homage to the memory of the great Pope Paul VI who dedicated his entire life to the Church. The Church is a real spiritual organism that prolongs in space and time the sacrifice of the Son of God, an apparently insignificant sacrifice in comparison with the dimensions of the world and of history but in God's eyes crucial. As the Letter to the Hebrews says and also the text we have just heard Jesus' sacrifice offered "once" sufficed for God to save the whole world (cf. Heb 9: 26, 28), because all the Love of the Son of God made man is condensed in that single oblation, just as all the widow's love for God and for her brethren is concentrated in this woman's action; nothing is lacking and there is nothing to add. The Church, which is ceaselessly born from the Eucharist, from Jesus' gift of self, is the continuation of this gift, this superabundance which is expressed in poverty, in the all that is offered in the fragment. It is Christ's Body that is given entirely, a body broken and shared in constant adherence to the will of its Head.

[Pope Benedict, homily Brescia 8 November 2009]

A marquisate is not enough for me, I aim at a Kingdom

2. Let us praise God together with the psalmist: he "is faithful for ever": the God of the covenant. He is the one who "brings justice to the oppressed", who "gives bread to the hungry" - as we ask him every day. God is the one who 'restores sight to the blind': he restores the sight of the spirit. He "raises up the fallen". He "upholds the orphan and the widow" . . . (Ps 146 [145]:6-9).

3. It is precisely the widow who is at the centre of today's liturgy of the Word. This is a well-known figure from the Gospel: the poor widow who threw into the treasury "two pennies, that is, one quintrin" (Mk 12:42) - (what is the approximate value of this coin?). Jesus observed "how the crowd threw coins into the treasury. And many rich people were throwing a lot of them" (Mk 12:41).

Seeing the widow and her offering he said to the disciples: "This widow has thrown more into the treasury than all the others . . . They all gave of their surplus; she, on the other hand, in her poverty, put in all she had, all she had to live on" (Mk 12:43-44).

4. The widow of the Gospel has her parallel in the old covenant. The first reading of the liturgy from the book of Kings, recalls another widow, that of Zarepta, who at the request of the prophet Elijah shared with him all that she had for herself and her son: bread and oil, even though what she had was only enough for the two of them.

And behold - according to Elijah's prediction - the miracle happened: the flour in the jar did not run out and the jar of oil was not emptied . . . and so it was for several days (cf. 1 Kings 17: 14-17).

5. A common characteristic unites both widows - the widow of the old covenant and the widow of the new covenant -. Both are poor and at the same time generous: they give all that is in their power. Everything they possess. Such generosity of heart is a manifestation of total reliance on God. And so today's liturgy rightly links these two figures with the first beatitude of Christ's Sermon on the Mount:

"Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven" (Mt 5:3). The 'poor in spirit' - like that widow of Zarepta in the time of Elijah, and that other in the temple of Jerusalem in the time of Christ - demonstrate in their poverty a great richness of spirit. For: the poor in spirit is rich in spirit. And only he who is rich in spirit can enrich others. Christ teaches that "theirs is the kingdom of heaven".

6. For us who participate in the Eucharistic sacrifice, this instruction is particularly important. Only when our presence here reveals that 'poverty in spirit' of which Christ's beatitude speaks, only then can we offer our offering to the great 'spiritual treasure' of the Church: can we bring this offering to the altar in that spirit which God, our creator, and Christ, our redeemer, expect from us.

The letter to the Hebrews speaks of Christ, the eternal priest, interceding on our behalf by presenting before God the Father the sacrifice of the cross on Golgotha. And this unique, most holy and indefinite value of Christ's sacrifice also embraces the offerings we bring to the altar. It is necessary that these offerings be similar to the offering of that widow in the Jerusalem temple, and also to the offering of the widow of Zarepta from the time of Elijah. It is necessary that these offerings of ours presented to the altar - our participation in the Eucharist - carry within them a sign of Christ's blessedness about the "poor in spirit".

7. The whole Church today meditates on the truth contained in these words of the liturgy. It is given to me today, as Bishop of Rome, to meditate on them together with you, the faithful of the parish of St Louis Gonzaga, at Parioli. Your patron, St Louis, lived to the full the evangelical beatitude of poverty in spirit, that is, of stripping oneself of earthly honours and goods in order to conquer true wealth, which is the Kingdom of God. In fact, he said to his father, Marquis of Castiglione delle Stiviere: 'A marquisate is not enough for me, I aim for a kingdom'; he was evidently referring to the Kingdom of Heaven. To realise his wish, Louis renounced his father's title and inheritance to enter the Roman novitiate of the Society of Jesus. He made himself poor in order to become rich. He would later note in one of his writings: 'Even princes are ashes, like the poor'. Just like the 'poor widow', he gave everything to the Lord with generosity and zeal, which has something of the heroic about it. She chose the humblest tasks for herself, dedicating herself to serving the sick, especially during the plague epidemic that struck Rome in 1590, and giving her life for them.

[Pope John Paul II, homily at the parish s. Luigi Gonzaga, 6 November 1988]

Quantity or Fullness

Gospel passage is composed of two parts: one that describes how not to be followers of Christ; the other offers an example of a Christian.

Let’s start with the first: what not to do. In the first part, Jesus accuses the scribes, the teachers of the law, of having three defects in their lifestyle: pride, greed and hypocrisy. They like “to have salutations in the market places and the best seats in the synagogues and the places of honor at feasts” (Mk 12:38-39). But beneath such solemn appearances they are hiding falsehood and injustice.

While flaunting themselves in public, they use their authority — as Jesus says — to devour “the houses of widows” (cf. v. 40); those who, along with orphans and foreigners, were considered to be the people most vulnerable and least protected. Lastly, Jesus says that the scribes, “for a pretence make long prayers” (v. 40). Even today we risk taking on these attitudes. For example, when prayer is separate from justice so that God cannot be worshiped, and causing harm to the poor. Or when one claims to love God, but instead offers him only grandiosity for one’s own advantage.

The second part of the Gospel follows this line of thinking. The scene is set in the temple of Jerusalem, precisely in the place where people are tossing coins as offerings. There are many rich people putting in large sums, and there is a poor woman, a widow, who contributes only two bits, two small coins. Jesus observes the woman carefully and calls the disciples’ attention to the sharp contrast of the scene.

The wealthy contributed with great ostentation what for them was superfluous, while the widow, Jesus says, “put in everything she had, her whole living” (v. 44). For this reason, Jesus says, she gave the most of all. Because of her extreme poverty, she could have offered a single coin to the temple and kept the other for herself. But she did not want to give just half to God; she divested herself of everything. In her poverty she understood that in having God, she had everything; she felt completely loved by him and in turn loved him completely. What a beautiful example this little old woman offers us!

Today Jesus also tells us that the benchmark is not quantity but fullness. There is a difference between quantity and fullness. You can have a lot of money and still be empty. There is no fullness in your heart. This week, think about the difference there is between quantity and fullness. It is not a matter of the wallet, but of the heart. There is a difference between the wallet and the heart.... There are diseases of the heart, which reduce the heart to the wallet.... This is not good! To love God “with all your heart” means to trust in him, in his providence, and to serve him in the poorest brothers and sisters without expecting anything in return.

Allow me to tell you a story, which happened in my previous diocese. A mother and her three children were at the table, the father was at work. They were eating Milan-style cutlets.... There was a knock at the door and one of the children — they were young, 5, 6 and the oldest was 7 — comes and says: “Mom, there is a beggar asking for something to eat”. And the mom, a good Christian, asks them: “What shall we do?” — “Let’s give him something, mom…” – “Ok”. She takes her fork and knife and cuts the cutlets in half. “Ah no, mom, no! Not like this! Take something from the fridge” — “No! Let’s make three sandwiches with this!”. The children learned that true charity is given, not with what is left over, but with what we need. That afternoon I am sure that the children were a bit hungry.... But this is how it’s done!

Faced with the needs of our neighbours, we are called — like these children and the halved cutlets — to deprive ourselves of essential things, not only the superfluous; we are called to give the time that is necessary, not only what is extra; we are called to give immediately and unconditionally some of our talent, not after using it for our own purposes or for our own group.

Let us ask the Lord to admit us to the school of this poor widow, whom Jesus places in the cathedra and presents as a teacher of the living Gospel even to the astonishment of the disciples. Through the intercession of Mary, the poor woman who gave her entire life to God for us, let us ask for a heart that is poor, but rich in glad and freely given generosity.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 8 November 2015]

33rd Sunday in O.T. (year C)

XXXIII Sunday in Ordinary Time C [16 November 2025]

First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Malachi (3:19-20a)

When Malachi wrote these words around 450 BC, the people were discouraged: faith seemed to be dying out, even among the priests of Jerusalem, who now celebrated worship in a superficial manner. Everyone asked themselves: 'What is God doing? Has he forgotten us? Life is unfair! The wicked succeed in everything, so what is the point of being the chosen people and observing the commandments? Where is God's justice?" The prophet then fulfils his task: to reawaken faith and inner energy. He rebukes priests and lay people, but above all he proclaims that God is just and that his plan of justice is advancing irresistibly. "Behold, the day of the Lord is coming": history is not a repeating cycle, but is moving towards fulfilment. For those who believe, this is a truth of faith: the day of the Lord is coming. Depending on the image that each person has of God, this coming can be frightening or arouse ardent expectation. But for those who recognise that God is Father, the day of the Lord is good news, a day of love and light. Malachi uses the image of the sun: "Behold, the day of the Lord is coming, burning like an oven." This is not a threat! At the beginning of the book, God says, "I love you" (Malachi 1:2) and "I am Father" (Malachi 1:6). The "furnace" is not punishment, but a symbol of God's burning love. Just as the disciples of Emmaus felt their hearts burning within them, so those who encounter God are enveloped in the warmth of his love. The 'sun of righteousness' is therefore a fire of love: on the day we encounter God, we will be immersed in this burning ocean of mercy. God cannot help but love, especially all that is poor, naked and defenceless. This is the very meaning of mercy: a heart that bends over misery. Malachi also speaks of judgement. The sun, in fact, can burn or heal: it is ambivalent. In the same way, the 'Sun of God' reveals everything, illuminating without leaving any shadows: no lie or hypocrisy can hide from its light. God's judgement is not destruction, but revelation and purification. The sun will 'burn' the arrogant and the wicked, but it will 'heal' those who fear his name. Arrogance and closed hearts will be consumed like straw; humility and faith will be transfigured. Pride and humility, selfishness and love coexist in each of us. God's judgement will take place within us: what is 'straw' will burn, what is 'good seed' will sprout in God's sun. It will be a process of inner purification, until the image and likeness of God shines within us. Malachi also uses two other images: that of the smelter, who purifies gold not to destroy it, but to make it shine in all its beauty; and that of the bleacher, who does not ruin the garment, but makes it shine. Thus, God's judgement is a work of light: everything that is love, service and mercy will be exalted; everything that is not love will disappear. In the end, only what reflects the face of God will remain. The historical context helps us to understand this text: Israel is experiencing a crisis of faith and hope after the exile; the priests are lukewarm and the people are disillusioned. The prophet's message: God is neither absent nor unjust. His 'day' will come: it is the moment when his justice and love will be fully manifested. The central image is the Sun of Justice, symbol of God's purifying love. Like the sun, divine love burns and heals, consumes evil and makes good flourish. In each of us, God does not condemn, but transforms everything into salvation by discerning what glorifies love and dissolves pride. Fire, the sun, the smelter and the bleacher indicate the purification that leads to the original beauty of man created in the image of God. Finally, there is nothing to fear: for those who believe, the day of the Lord reveals love. "The sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings" (Malachi 3:20).

Responsorial Psalm (97/98:5-6, 7-8, 9)

This psalm transports us ideally to the end of time, when all creation, renewed, joyfully acclaims the coming of the Kingdom of God. The text speaks of the sea and its riches, the world and its inhabitants, the rivers and the mountains: all creation is involved. St Paul, in his Letter to the Ephesians (1:9-10), reminds us that this is God's eternal plan: 'to bring all things in heaven and on earth together under one head, Christ'. God wants to reunite everything, to create full communion between the cosmos and creatures, to establish universal harmony. In the psalm, this harmony is already sung as accomplished: the sea roars, the rivers clap their hands, the mountains rejoice. It is God's dream, already announced by the prophet Isaiah (11:6-9): 'The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid... no one shall do evil or destruction on all my holy mountain'. But the reality is very different: man knows the dangers of the sea, conflicts with nature and with his fellow men. Creation is marked by struggle and disharmony. However, biblical faith knows that the day will come when the dream will become reality, because it is God's own plan. The role of prophets, such as Isaiah, is to revive the hope of this messianic Kingdom of justice and faithfulness. The Psalms also tirelessly repeat the reasons for this hope: Psalm 97(98) sings of the Kingdom of God as the restoration of order and universal peace. After so many unjust kings, a Kingdom of justice and righteousness is awaited. The people sing as if everything were already accomplished: "Sing hymns to the Lord who comes to judge the earth... and the peoples with righteousness." At the beginning of the psalm, the wonders of the past are recalled—the exodus from Egypt, God's faithfulness in the history of Israel—but now it is proclaimed that God is coming: his Kingdom is certain, even if not yet fully visible. The experience of the past becomes a guarantee of the future: God has already shown his faithfulness, and this allows the believer to joyfully anticipate the coming of the Kingdom. As Psalm 89(90) says: "A thousand years in your sight are like yesterday." And Saint Peter (2 Pt 3:8-9) reminds us that God does not delay his promise, but waits for the conversion of all. This psalm therefore echoes the promises of the prophet Malachi: "The sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings" (Mal 3:20). The singers of this psalm are the poor of the Lord, those who await the coming of Christ as light and warmth. Once it was only Israel that sang: "Acclaim the Lord, all the earth, acclaim your king!" But in the last days, all creation will join in this song of victory, no longer just the chosen people. In Hebrew, the verb "to acclaim" evokes the cry of triumph of the victor on the battlefield ("teru'ah"). But in the new world, this cry will no longer be one of war, but of joy and salvation, because — as Isaiah says (51:8): "My righteousness shall endure forever, my salvation from generation to generation." Jesus teaches us to pray, "Thy Kingdom come," which is the fulfilment of God's eternal dream: universal reconciliation and communion, in which all creation will sing in unison the justice and peace of its Lord.

Second Reading from the Second Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Thessalonians (3:7-12)

Saint Paul writes: "If anyone does not want to work, let him not eat" (2 Thessalonians 3:10). Today, this phrase cannot be repeated literally, because it does not refer to the unemployed of good will of our time, but to a completely different situation. Paul is not talking about those who cannot work, but those who do not want to work, taking advantage of the expectation of the imminent coming of the Lord to live in idleness. In Paul's world, there was no shortage of work. When he arrived in Corinth, he easily found employment with Priscilla and Aquila, who were in the same trade as him: tentmakers (Acts 18:1-3). His manual labour, weaving goat hair cloth, a skill he had learned in Tarsus in Cilicia, was tiring and not very profitable, but it allowed him not to be a burden to anyone: 'In toil and hardship, night and day we worked so as not to be a burden to anyone' (2 Thessalonians 3:8). This continuous work, supported also by the financial help of the Philippians, became for Paul a living testimony against the idleness of those who, convinced of the imminent return of Christ, had abandoned all commitment. His phrase 'if anyone does not want to work, let him not eat' is not a personal invention, but a common rabbinical saying, an expression of ancient wisdom that combined faith and concrete responsibility. The first reason Paul gives is respect for others: not taking advantage of the community, not living at the expense of others. Faith in the coming of the Kingdom must not become a pretext for passivity. On the contrary, waiting for the Kingdom translates into active and supportive commitment: Christians collaborate in the construction of the new world with their own hands, their own intelligence, their own dedication. Paul implicitly recalls the mandate of Genesis: 'Subdue the earth and subjugate it' (Gen 1:28), which does not mean exploiting it, but taking part in God's plan, transforming the earth into a place of justice and love, a foretaste of his Kingdom. The Kingdom is not born outside the world, but grows within history, through the collaboration of human beings. As Father Aimé Duval sings: "Your heaven will be made on earth with your arms." And as Khalil Gibran writes in The Prophet: "When you work, you realise a part of the dream of the earth... Work is love made visible." In this perspective, every gesture of love, care and service, even if unpaid, is a participation in the building of the Kingdom of God. To work, to create, to serve, is to collaborate with the Creator. Saint Peter reminds us: “With the Lord, one day is like a thousand years and a thousand years like one day... He is not slow in keeping his promise, but he is patient, wanting everyone to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:8-9). This means that the time of waiting is not empty, but a time entrusted to our responsibility. Every act of justice, every good work, every gesture of love hastens the coming of the Kingdom. Therefore, the text concludes, if we truly desire the Kingdom of God to come sooner, we have not a minute to lose. Here is a small spiritual summary: Idleness is not simply a lack of work, but a renunciation of collaboration with God. Work, in whatever form, is part of the divine dream: to make the earth a place of communion and justice. Waiting for the Kingdom does not mean escaping from the world, but committing ourselves to transforming it. Every gesture of love is a stone laid for the Kingdom to come. Those who work with a pure heart hasten the dawn of the 'Sun of Justice' promised by the prophets.

From the Gospel according to Luke (21:5-19)

'Not a hair of your head will be lost.' This is prophetic language, not literal. We see every day that hair is indeed lost! This shows that Jesus' words are not to be taken literally, but as symbolic language. Jesus, like the prophets before him, does not make predictions about the future: he preaches. He does not announce chronicles of events, but keys of faith to interpret history. His discourse on the end of the Temple should also be understood in this way: it is not a horoscope of the apocalypse, but a teaching on how to live the present with faith, especially when everything seems to be falling apart. The message is clear: 'Whatever happens... do not be afraid!' Jesus invites us not to base our lives on what is passing. The Temple of Jerusalem, restored by Herod and covered with gold, was splendid, but destined to collapse. Every earthly reality, even the most sacred or solid, is temporary. True stability does not lie in stones, but in God. Jesus does not offer details about the 'when' or 'how' of the Kingdom; he shifts the question: 'Be careful not to be deceived...'. We do not need to know the calendar of the future, but to live the present in faithfulness. Jesus warns his disciples: "Before all this, they will persecute you, they will drag you before kings and governors because of my Name." Luke, who writes after years of persecution, knows well how true this is: from Stephen to James, from Peter to Paul, to many others. But even in persecution, Jesus promises: "I will give you a word and wisdom that no one will be able to resist." This does not mean that Christians will be spared death — "they will kill some of you" — but that no violence can destroy what you are in God: "Not a hair of your head will be lost." It is a way of saying: your life is kept safe in the hands of the Father. Even through death, you remain alive in God's life. Jesus twice uses the expression "for my Name's sake." In Hebrew, "The Name" refers to God himself: to say "for the Name's sake" is to say "for God's sake." Thus Jesus reveals his own divinity: to suffer for his Name is to participate in the mystery of his love. In the Acts of the Apostles, Saint Luke shows Peter and John who, after being flogged, "went away rejoicing because they had been counted worthy of suffering for the Name of Jesus" (Acts 5:41). It is the same certainty that Saint Paul expresses in his Letter to the Romans: "Neither death nor life, nor any creature can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus" (Rom 8:38-39). Catastrophes, wars, epidemics — all these "shocks" of the world — must not take away our peace. The true sign of believers is the serenity that comes from trust. In the turmoil of the world, the calmness of God's children is already a testimony. Jesus sums it up in one word: "Take courage: I have overcome the world!" (Jn 16:33). And here is a spiritual synthesis: Jesus does not promise a life without trials, but a salvation stronger than death. Not even a hair...' means that no part of you is forgotten by God. Persecution does not destroy, but purifies faith. Nothing can separate us from the love of God: our security is the risen Christ. To believe is to remain steadfast, even when everything trembles.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Today with Me: the Wine that gets us out of the nest

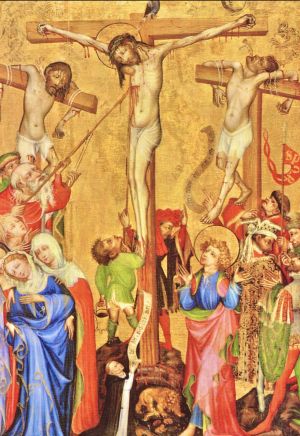

(Lk 23:35-43)

The Son is crucified among criminals. For political and religious power, he was a much worse danger.

According to Lk, only one outraged him; the other called Jesus by name and relied on him (v.42).

At the beginning of the Gospel the coming of the Lord is placed among the least of the earth.

He manifests himself to the world among impure and despised people [even certain that they must be incinerated of the Judge Messiah, and who therefore were afraid of him] not among the righteous and saints of the Temple.

Then his whole life takes place in the midst of tax collectors and sinners, because he came for them.

In fact: who brings back to the Father’s house? A guy any, representing all of us - a criminal who had committed murders - because all sins consist in taking away someone’s life and joy of living.

So that killer represents us. And Christ begins to build Family precisely with the criminal next door, who are we: sinners recovered from his unconditional Love.

In Lk the crowd is in disarray.

People do not insult the Faithful Son accused by religious authorities, but remain perplexed, they do not understand.

The people did not have healthy spiritual guides, capable of making the authentic features of God’s world be recognized - and vice versa, what made it caricature.

That of “universal King” is a title that today carries with it many misunderstandings - when attributed to the authentic Christ, reduced to zero.

This is because it’s confused with artificial magnitudes, magnificences of exteriority.

The regality of believers in Him is inapparent, all substance. Power that opens up new possibilities, even in dark dimension.

Nothing to do with the temptations to realize oneself by thinking in a trivial, hasty, outwardly, comfortable way, and promoting only oneself (vv.37.39).

In the Gospels - in fact - evil is presented not as a bad opponent and antagonist, but affable and complacent counselor, who seems to convey security from the unexpected, and make us win positions.

Friend who loves and protects us, so he gives the tips to stand up, impose, succeed.

But focussing on appearances ends up making us ignore and not understand the deep paths of the soul.

At the word «kingdom», Pilate immediately thought that of Tiberius (vv.2-4)

Here the size of the Kingdom is upside down: it doesn’t show the muscles.

His King stands us by, he is a Person able to create harmony of beauty within; a quieter road.

Salvation comes from what in our life is considered as bland and nothingness, yet it opens wide the infinite that dwells inside - the boundless of the primordial, present and final Friend.

He reverberates in the heart, and directs - Eternal who intimately resonates, even in tragic situations.

This comes even from those who - Jesus, benevolent oppressed - was valued a cursed by God and considered scum of society à la page.

Conversely, friendly Presence; wich makes us "see" and unlocks.

The radical difference between religiosity and Faith? The sense of an intimate and surprising Mystery that awakens us.

Wine, not «vinegar» [sour wine (v.36)]: corruption of love and of the celebration.

The God of religions drives out the contradictory and inadequate woman and man from Paradise. The Father welcomes them.

[34th Sunday in O.T. (year C), November 23, 2025, Christ the King]

Today with Me: The Wine that brings us out of our nest

(Lk 23:35-43)

The Son is crucified between criminals. For the political and religious powers, he was a far greater danger.

According to Luke, only one of them reviled him; the other called Jesus by name and entrusted himself to him (v. 42).

At the beginning of the Gospel, the coming of the Lord is placed among the least of the earth.

From the beginning, he reveals himself to the world among unclean and despised people [who were even certain that they would be put to death by the Messiah the judge, and who therefore feared him], not among the righteous and holy of the Temple.

Then his whole life unfolds among tax collectors and sinners, because he came for them.

In fact, who brings us back to the Father's house? Just anyone, who represents all of us - a criminal who had committed murder - because all sins consist in taking away someone's life and joy of living.

So that murderer represents us. And Christ begins to build his family with a criminal at his side, who is us: sinners redeemed by his unconditional love.

What proposals offer us a valid impetus and do not amputate precious parts of ourselves?

What do we believe can deify us, bringing us closer to a full life?

Who is a friend who does not interrupt us, and who is an enemy - capable of making us grow (or dehumanise us)?

In Luke, the crowd is in disarray.

The people do not insult the Faithful accused by the religious authorities, but remain perplexed, unable to understand.

The people have not had sound spiritual guides capable of helping them recognise their own world of God - and vice versa, what makes it caricatural.

The title of universal King is one that today carries with it many misunderstandings - when attributed to the authentic Christ, it is reduced to nothing.

This is because it is confused with fatuous merits, artificial grandeur, theatrical magnificence and mere appearance [mostly ridiculous].

The royalty of those who believe in Him is unapparent, but it is all substance. It is a power that opens up new possibilities, even in dark times.

It has nothing to do with the temptations of self-fulfilment through trivial, hasty, superficial, comfortable thinking and the promotion of oneself alone (vv. 37.39).

In the Gospels, in fact, evil is presented not as a wicked adversary and antagonist, but as an affable and complacent advisor who seems to convey security from the unexpected and help us gain positions.

A friend who loves and protects us, therefore giving us tips on how to assert ourselves, impose ourselves, and succeed. And yet affirming in things of social [but superficial] importance that degrade our personal vocation.

Even (as has often seemed to be the case, unfortunately) in the spiritual realm.

But focusing on appearances ends up making us ignore and not understand the deep paths of the soul.

On Calvary, the Lord achieves kingship, a way of crowning life, an elevation of self, diametrically opposed to what the evil one suggests.

And here he is again at the crucial appointment set from the beginning of his public life (Lk 4:1-13), at the moment of extreme weakness!

In short, we want to be great, capable of surpassing others, and well regarded, even in the spiritual life.

But to become village chiefs, we must be cunning or blend in with the crowd, and follow criteria that have nothing to do with the life of Jesus.

We must ally ourselves with important people, introduce ourselves, make ourselves known, learn to seduce, be quick, well-connected, agile, and skilful.

In this way, even on the path to God, we give in to the temptation of status, calibre, notoriety, consideration, visibility, and comfort. And we must keep our mouths shut, otherwise there will be no career.

The urge of the gut recommends: 'Come on, together we can do something big, and you will be the dominant one in the nest. Instead of just another failure, you will become someone to be revered'.

But the dimension of the Kingdom is upside down.

At the word 'kingdom', Pilate immediately thought of that of Tiberius (vv. 2-4).

Instead, at the end of his life, what was Jesus' throne? And the obsequious servants?

Below him was an audience that insulted and challenged him.

The bodyguards? Where did the ambitious ministers, generals and colonels, those who sprang to his orders, end up?

Two unfortunate souls, disfigured by their own mistakes, who represent us.

But someone recites the mantra until the end: 'Save yourself!'.

Christ and his close friends do not intend to destroy the soul, so they do not come down from the gallows; on the contrary, they recognise it as 'their own': a supreme opportunity.

We do not want to add more years, but more intensity to life.

We do not adapt our hearts to the old royalty, that of those who intimidate, flex their muscles, use their abilities and even their devout appearance only for their own gain - building situations of papier-mâché, without backbone.

These are very dangerous people: they are the gendarmes of an ambitious, competitive, cynical world. Accustomed to the flattering servility that makes everyone bow their heads.

They offer 'vinegar', sour wine (v. 36): the corruption of love and celebration.

Their bitter product is that love of the system of things, and a caricature of happiness linked to power that 'counts'.

If approved, they risk making us give up our desire for an alternative world and fall back on ourselves.

Instead, the criminal calls him by name, recognising him as a travelling companion, confidant and natural ally.

Someone who stands by him and is able to create inner harmony; a quieter path.

So, how do Victory and Peace relate to each other within us?

It is a 'time' that we perhaps do not yet know, despite the virtuosity of devout fulfilments (which sometimes take root in the worst disturbances).

By becoming more attentive and loving, less distant and competitive, we might respond in a surprising way to such a question:

Is it prevailing that brings a sense of harmony, liveliness and completeness, or vice versa?

What distracts us from the whirlpool of idols that divert our existence and confuse our destination?

Salvation comes from what is considered insipid and nothing in our lives, yet it opens up the infinity that already dwells within us - the boundlessness of the primordial, present and final Friend.

He reverberates in the heart and guides us - the Eternal One who resonates intimately, even in tragic situations.

This comes even from the one who - the benevolent, oppressed Jesus - was considered cursed by God and regarded as the scum of society à la page.

Conversely, a friendly Presence; one that makes us 'see' and unlocks us.

The radical difference between religiosity and Faith? The sense of an intimate and surprising Mystery that awakens us.

The God of religions drives contradictory and inadequate women and men out of Paradise. The Father welcomes them.

To internalise and live the message:

The leaders mock: 'You have abilities: think of yourself, assert yourself, be selfless; you must rise above, or at least float. Don't worry about anything else!'.

Which character do you recognise yourself in?

In moments of weakness, are you tempted by power, or do you look inside and see better - precisely by going through your inadequacy?

Right and wrong

In the Gospel we see that everyone asks Jesus to come down from the Cross. They mock him, but this is also a way of excusing themselves from blame as if to say: it is not our fault that you are hanging on the Cross; it is solely your fault because if you really were the Son of God, the King of the Jews, you would not stay there but would save yourself by coming down from that infamous scaffold.

Therefore, if you remain there it means that you are wrong and we are right. The tragedy that is played out beneath the Cross of Jesus is a universal tragedy; it concerns all people before God who reveals himself for what he is, namely, Love.

In the crucified Jesus the divinity is disfigured, stripped of all visible glory and yet is present and real. Faith alone can recognize it: the faith of Mary, who places in her heart too this last scene in the mosaic of her Son's life. She does not yet see the whole, but continues to trust in God, repeating once again with the same abandonment: “Behold, the handmaid of the Lord” (cf. Lk 1:38).

Then there is the faith of the Good Thief: a faith barely outlined but sufficient to assure him salvation: “Today you will be with me in Paradise” . This “with me” is crucial. Yes, it is this that saves him. Of course, the good thief is on the cross like Jesus, but above all he is on the Cross with Jesus. And, unlike the other evildoer and all those who taunt him, he does not ask Jesus to come done from the Cross nor to make him come down. Instead he says: “remember me when you come into your kingdom”.

The Good Thief sees Jesus on the Cross, disfigured and unrecognizable and yet he entrusts himself to him as to a king, indeed as to the King. The good thief believes what was written on the tablet over Jesus' head: “The King of the Jews”. He believed and entrusted himself. For this reason he was already, immediately, in the “today” of God, in Paradise, because Paradise is this: being with Jesus, being with God.

[Pope Benedict, homily at the Consistory, 21 November 2010]

“Regnavit a ligno Deus”!

The text of the Gospel of Saint Luke, now proclaimed, brings us back to the highly dramatic scene that takes place in “the place called Calvary” (Lk 23:33) and presents us with three groups of people gathered around the crucified Jesus, discussing his “figure” and his “end” in various ways. Who, in reality, is the one who is crucified there? While the common and anonymous people remain rather uncertain and limit themselves to watching, "the leaders, on the other hand, mocked him, saying, 'He saved others; let him save himself if he is the Christ of God, his chosen one. As we can see, their weapon is negative and destructive irony. But even the soldiers - the second group - mocked him and, almost in a tone of provocation and challenge, said to him, 'If you are the king of the Jews, save yourself', perhaps taking their cue from the very words of the inscription they saw above his head. Then there were the two criminals who disagreed with each other in judging their fellow sufferer: while one blasphemed him, repeating the contemptuous expressions of the soldiers and leaders, the other openly declared that Jesus "had done nothing wrong" and, turning to him, implored him: "Lord, remember me when you come into your kingdom" .

This is how, at the climax of the crucifixion, just as the life of the prophet of Nazareth is about to be taken, we can gather, even in the midst of discussions and contradictions, these arcane allusions to the king and the kingdom.

2. This scene is well known to you, dear brothers and sisters, and needs no further comment. But how appropriate and significant it is, and, I would say, how right and necessary it is that today's feast of Christ the King should be set against the backdrop of Calvary. We can say without hesitation that the kingship of Christ, which we celebrate and meditate on today, must always be referred to the event that took place on that hill and be understood in the saving mystery wrought there by Christ: I am referring to the event and mystery of the redemption of man. Christ Jesus, we must note, affirms himself as king at the very moment when, amid the pains and torments of the cross, amid the misunderstandings and blasphemies of those present, he agonises and dies. Truly, his is a singular kingship, such that only the eye of faith can recognise it: 'Regnavit a ligno Deus'!

3. The kingship of Christ, which springs from his death on Calvary and culminates in the inseparable event of the resurrection, calls us back to the centrality that belongs to him by reason of what he is and what he has done. Word of God and Son of God, first and foremost, "through whom - as we will shortly repeat in the "creed" - all things were created", he has an intrinsic, essential and inalienable primacy in the order of creation, in relation to which he is the supreme exemplary cause. And after 'the Word became flesh and dwelt among us' (Jn 1:14), also as man and son of man, he attained a second title in the order of redemption, through obedience to the Father's plan, through the suffering of death and the consequent triumph of the resurrection.

With this twofold primacy converging in him, we therefore have not only the right and duty, but also the satisfaction and honour of confessing his exalted lordship over things and men, which can be called kingship in a term that is certainly neither inappropriate nor metaphorical. "He humbled himself, becoming obedient unto death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and given him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord" (Phil 2:8-11).

This is the name of which the apostle speaks: it is the name of Lord, and it designates the incomparable dignity that belongs to him alone and places him alone—as I wrote at the beginning of my first encyclical—at the centre, indeed at the summit of the cosmos and of history. “Ave Dominus noster! Ave rex noster”!

4. But if we wish to consider, in addition to the titles and reasons, the nature and scope of the kingship of Christ our Lord, we cannot fail to refer to that power which he himself, on the verge of leaving this earth, defined as total and universal, placing it at the basis of the mission entrusted to the apostles: “All power in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you" (Mt 28:18-20). These words not only explicitly claim sovereign authority, but also indicate, in the very act of sharing it with the apostles, its ramification into distinct, albeit coordinated, spiritual functions. If, in fact, the risen Christ tells his disciples to go and reminds them of what he has already commanded, if he gives them the task of both teaching and baptising, this is explained by the fact that he himself, precisely by virtue of the supreme power that belongs to him, possesses these rights in full and is empowered to exercise these functions as king, teacher and priest.

There is certainly no need to ask which of these three titles comes first, because, in the general context of the salvific mission that Christ received from the Father, each of them corresponds to equally necessary and important functions. However, in order to remain faithful to the content of today's liturgy, it is appropriate to insist on the royal function and to focus our gaze, enlightened by faith, on the figure of Christ as king and lord.

In this regard, the exclusion of any reference of a political or temporal nature seems obvious.

To Pilate's formal question, "Are you the king of the Jews?" (Jn 18:33), Jesus explicitly replies that his kingdom is not of this world and, in response to the Roman procurator's insistence, he affirms, "You say that I am a king," adding immediately afterwards: "For this I came into the world, to bear witness to the truth" (Jn 18:37). In this way, he declares the exact dimension of his kingship and the sphere in which it is exercised: it is the spiritual dimension that includes, first and foremost, the truth to be proclaimed and served. His kingdom, even though it begins here on earth, has nothing earthly about it and transcends all human limitations, reaching towards its fulfilment beyond time, in the infinity of eternity.

5. It is to this kingdom that Christ the Lord has called us, giving us the gift of a vocation that is a participation in those powers of his that I have already mentioned. We are all at the service of the kingdom and, at the same time, by virtue of our baptismal consecration, we are invested with a dignity and a royal, priestly and prophetic office, so that we may effectively collaborate in its growth and spread. This theme, on which the Second Vatican Council so providentially insisted in its constitution on the Church and in its decree on the apostolate of the laity (cf. Lumen Gentium, 31-36; Apostolicam Actuositatem, 2-3), is certainly familiar to you, dear brothers and sisters and children of the diocese of Rome who are listening to me. But today, on the feast of Christ the King, I wish to recall it and strongly recommend it to your attention and sensitivity.

You have come to this sacred assembly as representatives and leaders of the Roman laity, who are most directly involved in apostolic action. Who better than you, given the duty of exemplarity that falls upon Christians in the city, is called upon to reflect on how to conceive and carry out such work on such a significant occasion? It is truly a service to the kingdom, and this is precisely why I have summoned you today to the Vatican Basilica, to encourage your hearts to render ever vigilant, concrete and generous service to the kingdom of Christ.

I know that, in view of the new pastoral year, you are studying the theme of 'community and communion', and you have based your reflections on the well-known words addressed by the Apostle John to the first baptised, which can be considered as the dynamic programme of every Christian community: 'What we have seen with our eyes, what we have contemplated and what our hands have touched, namely the Word of life... we proclaim to you too, so that you may be in communion with us' (1 Jn 1:1, 3).

Here, dear friends, is your plan for life and work: you, believers and Christians, lay people and committed priests, gathering the testimony of the apostles, have already seen Christ the Redeemer and King, you have encountered him in the reality of his human and divine, historical and transcendent presence, you have entered into communication with him, with his grace, with the truth and salvation he brings, and now, on the basis of this powerful experience, you intend to proclaim him to the city of Rome, to the people, families and communities who live there. This is a great task, a high honour, an ineffable gift: to serve Christ the King and to devote time, effort, intelligence and fervour to making him known, loved and followed, in the certainty that only in Christ - the way, the truth and the life (Jn 14:6) - society and individuals can find the true meaning of existence, the code of authentic values, the right moral line, the necessary strength in adversity, and light and hope regarding meta-historical realities. If your dignity is great and your mission magnificent, always be ready and joyful in serving Christ the King in every place, at every moment, in every environment.

I am well aware of the serious difficulties that exist in modern society, particularly in populous and frenetic cities such as Rome today. Despite certain complicated and sometimes hostile situations, I urge you never to lose heart. Take courage! Work zealously throughout the diocese and in individual parishes and communities, bringing everywhere the enthusiasm of your faith and your love for punctual and faithful service to Christ the Lord. So be it.

[Pope John Paul II, homily, 23 November 1980]

«Jesus, remember me when you come in your kingly power» (Lk 23:42).

On this last Sunday of the liturgical year, we join our voices to that of the criminal crucified beside Jesus, who acknowledged and acclaimed him a king. Amid cries of ridicule and humiliation, at the least triumphal and glorious moment possible, that thief was able to speak up and make his profession of faith. His were the last words Jesus heard, and Jesus’ own words in reply were the last he spoke before abandoning himself to the Father: “Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise” (Lk 23:43).

The chequered history of the thief seems, in an instant, to take on new meaning: he was meant to be there to accompany the Lord’s suffering. And that moment does nothing more than confirm the entire meaning of Jesus’ life: always and everywhere to offer salvation. The attitude of the good thief makes the horror and injustice of Calvary – where helplessness and incomprehension are met with jeers and mockery from those indifferent to the death of an innocent man – become a message of hope for all humanity. “Save yourself!” The shouts of scornful derision addressed to the innocent victim of suffering will not be the last word; rather, they will awaken a response from those who let their hearts be touched, who choose compassion as the authentic way to shape history.

Today, in this place, we want to renew our faith and our commitment. We know too well the history of our failures, sins and limitations, even as the good thief did, but we do not want them to be what determines or defines our present and future. We know how readily all of us can take the easy route of shouting out: “Save yourself!” and choose not to think about our responsibility to alleviate the suffering of innocent people all around us. This land has experienced, as few countries have, the destructive power of which we humans are capable. Like the good thief, we want to speak up and profess our faith, to defend and assist the Lord, the innocent man of sorrows. We want to accompany him in his ordeal, to stand by him in his isolation and abandonment, and to hear once more that salvation is the word the Father desires to speak to all: “Today you will be with me in Paradise”.

Saint Paul Miki and his companions gave their lives in courageous witness to that salvation and certainty, along with the hundreds of martyrs whose witness is a distinguished element of your spiritual heritage. We want to follow in their path, to walk in their footsteps and to profess courageously that the love poured out in sacrifice for us by Christ crucified is capable of overcoming all manner of hatred, selfishness, mockery and evasion. It is capable of defeating all those forms of facile pessimism or comfortable indolence that paralyze good actions and decisions. As the Second Vatican Council reminds us, they are sadly mistaken who believe that, because we have here no lasting city and keep our gaze fixed on the future, we can ignore our responsibility for the world in which we live. They fail to see that the very faith we profess obliges us to live and work in a way that points to the noble vocation to which we have been called (cf. Gaudium et Spes, 43).

Our faith is in the God of the living. Christ is alive and at work in our midst, leading all of us to the fullness of life. He is alive and wants us to be alive; he is our hope (cf. Christus Vivit, 1). Each day we pray: Lord, may your kingdom come. With these words, we want our own lives and actions to become a hymn of praise. If, as missionary disciples, our mission is to be witnesses and heralds of things to come, we cannot become resigned in the face of evil in any of its forms. Rather, we are called to be a leaven of Christ’s Kingdom wherever we find ourselves: in the family, at work or in society at large. We are to be a little opening through which the Spirit continues to breathe hope among peoples. The kingdom of heaven is our common goal, a goal that cannot be only about tomorrow. We have to implore it and begin to experience it today, amid the indifference that so often surrounds and silences the sick and disabled, the elderly and the abandoned, refugees and immigrant workers. All of them are a living sacrament of Christ our King (cf. Mt25:31-46). For “if we have truly started out anew from the contemplation of Christ, we must learn to see him especially in the faces of those with whom he himself wished to be identified” (John Paul II, Novo Millennio Ineunte, 49).

On that day at Calvary, many voices remained silent; others jeered. Only the thief’s voice rose to the defence of the innocent victim of suffering. His was a brave profession of faith. Each of us has the same possibility: we can choose to remain silent, to jeer or to prophesy.

Dear brothers and sisters, Nagasaki bears in its soul a wound difficult to heal, a scar born of the incomprehensible suffering endured by so many innocent victims of wars past and those of the present, when a third World War is being waged piecemeal. Let us lift our voices here and pray together for all those who even now are suffering in their flesh from this sin that cries out to heaven. May more and more persons be like the good thief and choose not to remain silent and jeer, but bear prophetic witness instead to a kingdom of truth and justice, of holiness and grace, of love and peace (cf. Roman Missal, Preface of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe).

[Pope Francis, homily in Nagasaki, 24 November 2019]

It is not an anecdote. It is a decisive historical fact! This scene is decisive for our faith; and it is also decisive for the Church’s mission (Pope Francis)

Non è un aneddoto. E’ un fatto storico decisivo! Questa scena è decisiva per la nostra fede; ed è decisiva anche per la missione della Chiesa (Papa Francesco)

Being considered strong, capable of commanding, excellent, pristine, magnificent, performing, extraordinary, glorious… harms people. It puts a mask on us, makes us one-sided; takes away understanding. It floats the character we are sitting in, above reality

Essere considerati forti, capaci di comandare, eccellenti, incontaminati, magnifici, performanti, straordinari, gloriosi… danneggia le persone. Ci mette una maschera, rende unilaterali; toglie la comprensione. Fa galleggiare il personaggio in cui siamo seduti, al di sopra della realtà

The paralytic is not a paralytic

Il paralitico non è un paralitico

The Kingdom of God is precisely the presence of truth and love and thus is healing in the depths of our being. One therefore understands why his preaching and the cures he works always go together: in fact, they form one message of hope and salvation (Pope Benedict)

Il Regno di Dio è proprio la presenza della verità e dell’amore e così è guarigione nella profondità del nostro essere. Si comprende, pertanto, perché la sua predicazione e le guarigioni che opera siano sempre unite: formano infatti un unico messaggio di speranza e di salvezza (Papa Benedetto)

To repent and believe in the Gospel are not two different things or in some way only juxtaposed, but express the same reality (Pope Benedict)

Convertirsi e credere al Vangelo non sono due cose diverse o in qualche modo soltanto accostate tra loro, ma esprimono la medesima realtà (Papa Benedetto)

The fire of God's creative and redeeming love burns sin and destroys it and takes possession of the soul, which becomes the home of the Most High! (Pope John Paul II)

Il fuoco dell’amore creatore e redentore di Dio brucia il peccato e lo distrugge e prende possesso dell’anima, che diventa abitazione dell’Altissimo! (Papa Giovanni Paolo II)

«The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor» (Lk 4:18). Every minister of God has to make his own these words spoken by Jesus in Nazareth [John Paul II]

«Lo Spirito del Signore è sopra di me; per questo mi ha consacrato con l'unzione e mi ha mandato per annunziare un lieto messaggio» (Lc 4, 18). Ogni ministro di Dio deve far sue nella propria vita queste parole pronunciate da Gesù di Nazareth [Giovanni Paolo II]

It is He himself who comes to meet us, who lowers Heaven to stretch out his hand to us and raise us to his heights [Pope Benedict]

È Lui stesso che ci viene incontro, abbassa il cielo per tenderci la mano e portarci alla sua altezza [Papa Benedetto]

Christ reveals his identity of Messiah, Israel's bridegroom, who came for the betrothal with his people. Those who recognize and welcome him are celebrating. However, he will have to be rejected and killed precisely by his own; at that moment, during his Passion and death, the hour of mourning and fasting will come (Pope Benedict)

Cristo rivela la sua identità di Messia, Sposo d'Israele, venuto per le nozze con il suo popolo. Quelli che lo riconoscono e lo accolgono con fede sono in festa. Egli però dovrà essere rifiutato e ucciso proprio dai suoi: in quel momento, durante la sua passione e la sua morte, verrà l'ora del lutto e del digiuno (Papa Benedetto)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.