Argentino Quintavalle

Argentino Quintavalle è studioso biblico ed esperto in Protestantesimo e Giudaismo. Autore del libro “Apocalisse - commento esegetico” (disponibile su Amazon) e specializzato in catechesi per protestanti che desiderano tornare nella Chiesa Cattolica.

(Mt 11:2-11)

Matthew 11:2 Now John, who was in prison, heard about the works of Christ, and sent his disciples to ask him,

Matthew 11:3 'Are you the one who is to come, or should we wait for another?'.

Matthew 11:4 Jesus answered, 'Go and tell John what you hear and see:

Matthew 11:5 The blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have the good news preached to them.

Matthew 11:6 and blessed is anyone who does not take offence at me."

Matthew 11:7 As they were going away, Jesus began to speak to the crowds about John: "What did you go out into the desert to see? A reed swayed by the wind?

Jesus' answer to John the Baptist's question is not a theoretical answer, a simple explanation, or a classic retort. There is nothing to explain. It is not as if someone explains the truth of lunch to us at midday: it is better for them to feed us, otherwise it means they are leaving us hungry. The truth is the reality that nourishes us. Abstract truth and reflection are one thing; these are all good things, but we cannot live without reality. Truth is the reality we experience, and that is why Jesus' answer is not theoretical, but says: go and report what you hear and see.

Here, then, the works of Christ begin to take shape: 'The blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have the good news preached to them' (v. 5). No one can bear witness to himself. Not even Jesus Christ can bear witness and affirm the truth about himself. He can say it, but it must always be confirmed by other witnesses. In this case, Jesus does not ask for confirmation from men. He asks that Scripture itself bear witness to him.

His words are taken from the prophet Isaiah, to whom Jesus refers the disciples of John the Baptist, because in them lies the key to understanding his work. Only the Word, therefore, is able to reveal and make understood the mystery of Jesus Christ. In Jesus, the prophecies that Isaiah pronounced about the Messiah of God are fulfilled. Jesus is truly the one who was to come, the herchómenos.

The healing of the blind speaks of man's openness to the light of faith, it is enlightenment; man's problem is seeing reality. We do not see reality, we see our hypotheses about reality. And the reality is that we are children of God, created to be children, and to recover our sight and be enlightened is to have understood this. Then life has light, otherwise life is dull.

The healing of the deaf speaks of the ability to receive the Word; the lepers, a metaphor for a humanity degraded by sin, are healed by the proclamation they receive; the lame, with their limping and uncertain gait, are a metaphor for the doubtful, the uncertain, the weak in faith, who are restored to the firmness of their belief; just as the dead, a symbol of the pagan world and of sinners far from God, are also called to follow, and are also made participants in divine life. Finally, all the poor are given the gift of the good news: God has returned among men and reaches out to them, drawing them to Himself. The latter does not seem to be a miracle, and yet it is perhaps the most specific and decisive sign: that Jesus is God's envoy is proven by miracles, but it is his predilection for the poor that reveals the novelty of his messianic choice. A new creation is taking place; God is generating new men. This is the good news announced to all the poor, that is, to all situations of affliction, deprivation, need, and waiting.

"And blessed is he who is not scandalised by me" (v. 6). In the Beatitudes, Jesus declares blessed the poor, the afflicted, the meek, the merciful, the pure of heart, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the peacemakers, the persecuted, etc. Now Jesus says blessed is he who is not scandalised by me. Why? Because he is the poor, the afflicted, the pure of heart, the peacemaker, the meek, and for this reason he is persecuted, afflicted, rejected, insulted: he is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world, and whoever does not take offence at me is blessed, has understood all the Beatitudes. So the crucial point is to understand who he is, through what he does and says. This is how he responds to the Baptist. Accepting Jesus means entering into a new way of understanding our relationship with God and our relationship with others - and for many this means scandal. Jesus says that for those who are not scandalised by the novelty of his message, he will be a source of blessedness, a way of feeling truly happy.

"What did you go out to the desert to see? A reed swayed by the wind?" Jesus' questions, while highlighting the figure of the Baptist, also constitute an indictment of the Jews' inability to grasp his true significance. Two basic attitudes towards the Baptist emerge, which mirror those towards Jesus; in this way, John is not only the precursor of Jesus in that he announces him, but also in that he anticipates him, becoming a sort of prefiguration of him: a) there are those who rush to see and listen to John, driven mainly by curiosity, but without grasping the greatness and meaning of his preaching and his mission; b) there are those who had a true understanding of him, but one that was limited and incomplete.

The first two questions asked about the Baptist are intended to disapprove of superficial behaviour and, precisely for this reason, incapable of grasping the Mystery hidden in that man, who is wholehearted and far removed from compromises and palace intrigues, shunning comforts and focusing entirely on the herchómenos.

Jesus asks: What did you go out to the desert to see? The crowds went out to the desert. The Baptist is the man of the Exodus. Those who are not willing to make the exodus, to go out into the desert, to embark on a new journey, will never meet the Lord. The Baptist is the prototype of the man who meets the Lord because he is the first to go out into the desert. What did you go out to see? A reed swaying in the wind? Obviously, the answer is no. What is a reed swaying in the wind? It is the man who tries to please in order to be liked. The Baptist has something to teach us; he is not a reed swaying in the wind of opinions, but he is the one who is steadfast before God. The reed bends with every wind, small or large. John is not a reed swayed by the wind, bent by the thoughts of men. He does not follow the fashions of thought. He follows the thoughts of God. John is firmly rooted in the thoughts of God. This is his credibility. If his preaching is credible, it is compelling. Uncredible preaching can never compel a person.

A man who wants to preach and teach, if he accepts other thoughts, attests that God's thought is not everything to him. By accepting other thoughts, he relativises God's thought, making it imperfect, since it must be made perfect by the addition of human thoughts. This is the folly of those endless reeds blown by the wind that are Christians who allow themselves to be overwhelmed by the thoughts of the world.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(Romans 15:4-9)

Romans 15:4 Now all that was written in former days was written for our instruction, that through endurance and through the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope.

Romans 15:5 May the God of perseverance and consolation grant you to have the same feelings towards one another as Christ Jesus had,

Romans 15:6 so that with one heart and one voice you may glorify God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Romans 15:7 Therefore, accept one another, just as Christ has accepted you, for the glory of God.

Paul wants Christians to know that what was written in the Old Testament serves as our instruction. When Christians learn what happened in the past, they find motivation to persevere, they are comforted in the present, and they look forward to the future with hope. The perseverance and comfort that come from Scripture are those that arise from the faith that every sacrifice we have lived, offered, and lifted up to God will not go unrewarded. This fruit ripens on our perseverance, which must be until the end.

All the sufferings of the present world are worthless in comparison to the glory that God will give us. For this reason, we must always keep alive our hope of the future glory with which we will be clothed. The strength to persevere comes from this hope, and it is necessary to keep it alive; if we lose sight of hope, then we easily fall away from faith and our soul is lost in the small and useless things of this world. Hope is kept alive by conforming our lives to Christ. Outside of this law, all that remains for the Christian is bewilderment, confusion, and abandonment of the path undertaken.

God is the God of perseverance and consolation (v. 5). He is the God of perseverance because he never tires of seeking man for his salvation. The entire Old Testament is sustained by this perseverance of God, who knows no rest. He is the God who perseveres eternally in his love for man and who gives him consolation. God's consolation is that strength that pours out upon us and urges us to persevere to the end. Without God's perseverance, man would have been without hope for a long time. Without God's consolation, no one would have the strength to persevere, to move forward. Without God's consolation, we would have a Christianity of sadness and despair.

Paul raises this prayer to God and asks him to pour out on the Romans and on every other believer, that they may have the same feelings towards one another, following the example of Christ Jesus. Christ is the model that Christians must always be inspired by. Christ is the example to imitate. Christ is the hermeneutical principle of the life of each of his disciples. If Christians are the fruit of God's persevering love, they too must persevere in love for their neighbour. Since Christians have the strength to move forward because the Lord pours out his consolation on their path, Christians too must become instruments of consolation for their brothers and sisters. They must exhort, help and encourage. True communion does not arise from the presumption of a justice due to us, but from the awareness of a guilt that includes everyone, and of a grace that is simply a gift. We think well of our brothers and sisters not because we believe in their goodness, but because we believe in the One who makes us good. It is the awareness of sin and the awareness of grace that gives foundation and stability to fraternal love.

As Christ has welcomed us, so we must welcome one another. Christ welcomed us all when we had nothing but our need for salvation. Christ welcomed us by taking on our flesh and blood, taking upon himself our infirmities, our illnesses, our sins. He welcomed us by loving us to the end. Christ still welcomes us by exercising his eternal priesthood, interceding for us so that we may always find grace with God and be saved and redeemed by him.

Christ did everything for the glory of God. Christians too must welcome their brothers and sisters for the glory of God. God wants each of us to love our brothers and sisters as Jesus Christ loved them. If Christians observe this commandment, great glory rises to God. Christians must be singers of God's glory. They must ensure that the whole world glorifies the heavenly Father for their love towards their brothers and sisters.

We know well that only Jesus perfectly fulfilled the Father's will. By meditating on Christ and examining his life, Christians too can prepare themselves to give glory to the Father, which is the purpose of their lives.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(Mt 24:37–44)

Matthew 24:37 As it was in the days of Noah, so shall it be at the coming of the Son of Man.

Matthew 24:38 For as in the days before the flood, they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day Noah entered the ark,

Matthew 24:39 and they knew nothing until the flood came and swept them all away, so will be the coming of the Son of Man.

Matthew 24:40 Then two men will be in the field; one will be taken and the other left.

Matthew 24:41 Two women will be grinding at the mill; one will be taken and the other left.

Matthew 24:42 Therefore keep watch, because you do not know on what day your Lord will come.

Matthew 24:43 For this, consider: if the homeowner knew at what time of night the thief was coming, he would stay awake and not let his house be broken into.

Matthew 24:44 Therefore, you also must be ready, for at an hour you do not expect, the Son of Man will come.

The theme of this passage is the uncertainty of the time of the "parousia" and the accompanying end of time. The return of Christ (= the Son of Man) is certain, but at the same time it is completely unexpected. Since the time of his coming is unknown, Christians are called to be in a state of constant readiness.

The theme of judgement is clear. Jesus compares those who live in the final phase of history (which can happen in any generation) to the generation of Noah's time, which was overwhelmed by the flood. No one expected it, so everyone was suddenly caught up in a cataclysm that left no escape.

In v. 38, in Greek, we have a nice euphony, pleasing to the ear:

trōgontes kai pinontes gamountes kai gamizontes,

lit., "eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage."

No special meaning should be read into these participles. They simply stand as indicators of living daily life (eating and drinking) and planning for the future (marriages). In Noah's day, people were unaware of anything other than their own life of pleasure; and they had no idea of the judgement that was coming upon them: "and they did not realise anything (i.e. the imminent danger) until the flood ("kataklysmòs") came and swallowed them all up". The parousia of the Son of Man, similarly, will come suddenly upon an unsuspecting generation, which is going about its ordinary activities. This triggers a comparison between the times of Noah and the last days.

The insistent emphasis on eating, drinking, marrying and giving in marriage gives the idea of a humanity entirely intent on organising its own time, rooted in its own affairs, without paying attention to the signs that are sent to it; there is no room for anything but its own interests. People, in the normality of life, in the routine of eating and marrying, lived as if the world would never end, unprepared for the disaster that was about to come, with no expectation that things could change. Men, unaware of the tragic fate that awaited them, neglected what was essential for their survival: instead of preparing means of salvation like Noah, they were absorbed in their daily affairs and intent on blissfully enjoying life.

In the same way that humanity ignored the impending judgement, so the people of Jesus' time rejected Him and His message, and were overwhelmed by the devastation that struck Jerusalem and the temple. The same scenario will also occur in the last days. The parousia and the end times will come suddenly, and the story of Noah is used as a warning about the suddenness of disaster for those who are unprepared. They are unprepared because they do not take the gospel message into consideration and consequently believe the lie and reject the truth.

On that day, there will be a division among humanity. This is described very vividly in the reference to two men working in a field and two women grinding at the mill. They are going about their normal activities, unaware of what is about to happen, when suddenly one of them is taken and the other is left, where 'being taken' means being saved, and 'being left' means perishing in the impending destruction. This taking has the meaning of safeguarding, of placing under one's protection and, therefore, of election; while being left has the meaning of being abandoned to one's fate.

The fact that there are always two people involved does not indicate a quantitative percentage, but rather two conditions, two states of life: those who are faithful and those who are not; while the use of two characters, male and female, indicates the generality of humanity. The fact that they are caught in the field and at the mill indicates how the coming of the Lord will surprise them as they go about their daily business, suddenly and unexpectedly, just as in Noah's time people were caught up in the cataclysm while engaged in the ordinary activities of life.

One lives superficially: he eats, marries, works, but everything slips away; another eats, marries, works and on Sundays, instead of going to the beach, goes to listen to the Gospel. Everyone works during the week, but there is a way of living life with a different awareness instead of thinking only about eating and having fun.

Christians must not allow themselves to be surprised by such an unexpected event. They know very well what awaits them and that the rapidity of the final events does not allow them to think about conversion at the last moment. The things of God happen suddenly. Everything is sudden when the Lord acts, hence the urgent need to be always vigilant. When the Lord comes, and he will come suddenly, he must find us ready. It is our duty to prepare for the parousia without calculating its date, but by living ready and attentive to God's warnings. Being prepared does not mean sitting back and waiting, it means being engaged in faithful service to the One who is coming.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

Luke 23:35-43

34th Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C)

Luke 23:35 The people stood by and watched, but the leaders mocked him, saying, 'He saved others; let him save himself if he is the Christ of God, his chosen one.'

Luke 23:36 The soldiers also mocked him, coming up to him and offering him vinegar, and saying,

Luke 23:37 'If you are the King of the Jews, save yourself.'

Luke 23:38 There was also an inscription above his head: 'This is the King of the Jews'.

Luke 23:39 One of the criminals hanging on the cross insulted him, saying, 'Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!

Luke 23:40 But the other rebuked him, saying, 'Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation?

Luke 23:41 We are indeed justly condemned, for we are receiving the due reward for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong.'

Luke 23:42 And he added, "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom."

Luke 23:43 He replied, "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise."

First scene: Jesus, crucified and mocked, is proclaimed Christ and King of the Jews (vv. 33-38).

These verses report the title that outlines Jesus' identity and that those present attest to from their own perspective. The leaders of the people, sensitive to messianic expectations, challenge Jesus to show himself for what he claimed to be, that is, the "Christ of God." This title qualifies Jesus as the Messiah "chosen" by God, thus linking him to a mission he had to accomplish.

This suggests that, in some way, the challenge that the leaders of the people had thrown down to Jesus was not merely ironic or mocking, but that they intended to test Jesus in his presumed identity as Messiah. Such a request on the part of the Jews was in keeping with their mentality, which was to seek proof of divine or messianic claims.

The second group of people are the soldiers, who, unlike the first, the evangelist points out, mocked Jesus. The soldiers also reveal a certain contempt for the Jews, pointing to the crucified man as their king. A kingship, however, which, beyond the irony of the soldiers and the resentment of the Jews, Pilate officially decreed on the cartouche placed on the cross, which indicated the reason for the condemnation and which the condemned man carried around his neck on his way to the place of execution or, sometimes, a servant carried in front of him, so that, along the way, everyone would be aware of the reason for the condemnation as a warning. It is precisely this official decree by Pilate that gives the title 'King of the Jews' a transhistorical significance.

This first scene thus takes on fundamental importance not only for the definition of Jesus' identity, but also for the meaning of his death. All this is so important to Luke that, from the outset, he places the entire people as witnesses to these events: "And the people stood by and watched." Which people are we talking about here? It is conceivable that it is the Jewish people. But it is also conceivable that Luke goes far beyond the narrow confines of Palestine and sees here the great people of believers, called to be witnesses of the cross of Christ.

Second scene: Jesus recognised as Messiah, King and Saviour (vv. 39-43).

If the previous scene attested to Jesus' identity as Messiah and King, this scene demonstrates what has been attested. In v. 39, the focus shifts from the Jewish and Roman mockers to the two criminals. There is a change of scene here, which in some way ties in with the previous scene. The criminal, in fact, takes up the attestation of v. 35, in which Jesus was recognised as the Saviour Christ, and tries to use it to his advantage.

Verses 40-41, which report the intervention of the second criminal against his companion, have the purpose of attesting to Jesus' innocence. Verses 42-43 constitute the climax of this scene. After defending Jesus, the second criminal now gives his full testimony of faith. A faith that speaks of openness and abandonment of himself to Jesus, implicitly recognised here in that 'your kingdom' as King.

Jesus' response is an attestation of his saving power, which is not separate from the cross, but is realised in the cross. A salvation that will not come at the end of time, but in the present day of man: 'today you will be with me'. Jesus' response to the evildoer, but perhaps it is better now to call him a disciple, is particularly significant: 'today you will be with me in paradise'. Salvation, therefore, consists in being 'with Jesus', and he is found 'in paradise', that is, in the very dimension of God, which is the very life of God. The reference to Genesis, and more precisely to Gen 2:8, where the term 'paradeison' (paradise) appears for the first time in the Septuagint Bible, is not accidental. There we read: 'Then the Lord God planted a garden (paradeison) in Eden, in the east, and placed there the man whom he had formed'. Paradise, therefore, is a place of delights where God placed man. Man's natural habitat is not, therefore, this space-time dimension, deeply marked by sin and subject to the degradation of death, but the very dimension of God. Salvation, then, consists in God's action to restore man to his original dimension, when man and with him the whole of creation shone with the light of God. In fact, when God said, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness" (Gen 1:26-27), he created a being who, in that image and likeness, was part of His life. And that "today you will be with me in paradise" expresses the fulfilment of God's intention: to bring man back to Himself, from whence he had dramatically and tragically departed. And this has now been accomplished in the crucified Christ, who is "foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved, it is the power of God" (1 Cor 1:18).

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(2 Thessalonians 3:7-12)

2 Thessalonians 3:7 For you know how you ought to imitate us, because we did not live idly among you,

2 Thessalonians 3:8 nor did we eat anyone's bread without paying for it, but we worked hard night and day, labouring and toiling so that we would not be a burden to any of you.

2 Thessalonians 3:9 Not that we had no right to this, but to give you an example to imitate.

Paul says: remember our behaviour, that during our work among you, instead of shirking our duty to earn a living, we took on hard work so as not to be supported by the community. Paul, even before being a teacher, practises what he preaches. Every preacher must be able to combine theory and practice.

Conscience is educated not only through teaching, but above all through life, through example. Others must not only hear what is good and true, but they must also see what is good and true, because faith is either visible or it is not faith. Paul is not only a teacher who preaches, admonishes and teaches the faith, he is first and foremost someone who shows all these things and shows them through his life. He is both a teacher of life and a teacher of words. The two must always go together. It would be a serious spiritual loss if the two were to be separated.

Here, therefore, it is not a question of remembering a teaching, but of the duty to imitate the preachers of the gospel, who were not idlers. In other words, the preachers of the gospel did not take advantage of the hospitality of some Christians. Let us be clear, Paul is not saying that he never ate for free in other people's homes, but that he never demanded his sustenance.

Paul subjected himself to the harsh law of work for the sake of the gospel; he did not want to be mistaken for one of those itinerant preachers who moved from place to place selling theories, often only illusions, in exchange for sustenance. By supporting himself with his own hands, the apostle freed his message from any suspicion, and to do so he had renounced his right to be supported. This is the fairness of the apostle.

But there is also another reason why Paul worked: 'so as not to be a burden to any of you', a reason of charity. He did not want to cause difficulties for anyone, even if that anyone would have gladly done so.

Three principles are at stake here: the principle of justice, that of charity and that of evangelisation. The principle of justice says that every worker is entitled to his wages. Paul offers them the life of the soul; the Thessalonians offer him what he needs for the life of his body. This is justice: one thing for one thing, a gift for a gift, a service for a service.

But Paul does not want his relationship with the Thessalonians to be based on justice. For reasons of the gospel, he wants it to be based on charity instead. Charity is a one-way gift. Paul wants to give and that's it. He has decided to make his life a service of love. By proclaiming the gospel and living it in its deepest essence, he leaves the Thessalonians with the true model of how to live the gospel, how to proclaim it and how to put it into practice.

Now, if they want, they know what the Gospel is, they know it because they have seen it in Paul. Having seen it, they too can proclaim it and put it into practice. Paul decides to preach the Gospel freely because the Gospel is the free gift of God's love in Christ through the work of the Holy Spirit.

In the painful decline of the Church today, there are those who hope for a rebirth from below. But the Church was born from the proclamation of the apostles. It is up to those in charge to shed light, bring clarity, and point out the paths to follow in accordance with the Gospel of Christ... but those in charge must also be supported and encouraged.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse - Exegetical Commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(1 Cor 3:9c-11, 16-17)

1 Corinthians 3:9c You are God's building.

1 Corinthians 3:10 According to the grace of God given to me, like a skilled master builder I laid a foundation, and someone else is building upon it. But let each one take care how he builds upon it.

1 Corinthians 3:11 For no one can lay any foundation other than the one already laid, which is Jesus Christ.

1 Corinthians 3:16 Do you not know that you are God's temple and that God's Spirit dwells in you?

1 Corinthians 3:17 If anyone destroys God's temple, God will destroy him. For God's temple is holy, and you are that temple.

Evangelising means laying the foundation, that is, Jesus Christ, the Saviour and Redeemer, the Messiah of God for the salvation of all who believe. But the foundation is not enough. Paul says that he worked like a skilled architect. He acknowledges that he always acted with wisdom, but he also acknowledges that he only laid the foundation of faith in Corinth. It is then up to those who come after him to build on that foundation.

There are those who lay the foundation and those who build on it; there are those who dig deep and those who raise the building up to the sky. Without this communion of work, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to work in the Lord's vineyard. However, Paul does not stop at enunciating the principles of communion, but warns: let everyone be careful how they build!

Anyone who should or would want to build God's building without the foundation that is Jesus Christ would work in vain, waste their time unnecessarily, and there would be no salvation. Christ is the cornerstone of God's house. Our faith confesses that He alone is the Redeemer of humanity, the Messiah of God, the Saviour of mankind. Our faith confesses that Jesus is the way to access God and for God to dwell and live in our hearts.

Placing Jesus Christ as the foundation of God's building has only one meaning: placing his cross as the only way of salvation and redemption. And just as there is one foundation, so too must there be one building, one community of believers in Christ. When we forget our calling, which is to attain perfect conformity to Christ and his cross, each of us may be tempted to make ourselves the foundation, the cornerstone. When this happens, it is the destruction of the one building. Small huts arise where each person becomes lord and god over his brothers and sisters. The community of believers itself dies, lacking the principle of unity, and in this way everyone goes their own way and follows winding paths that do not lead to salvation.

For this reason, Paul warns everyone to be careful how they build upon it. But also to be careful to build only on this one foundation, which is Jesus Christ.

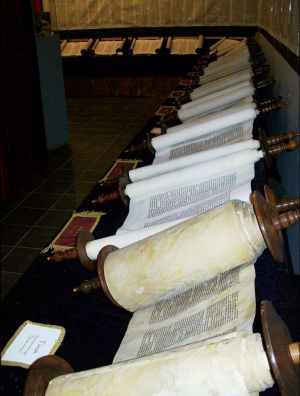

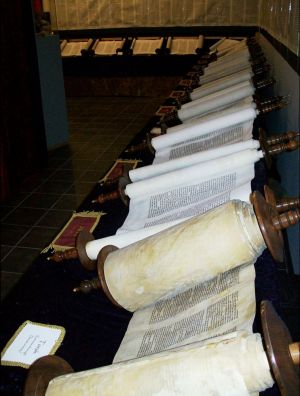

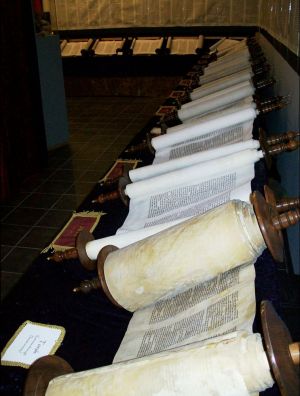

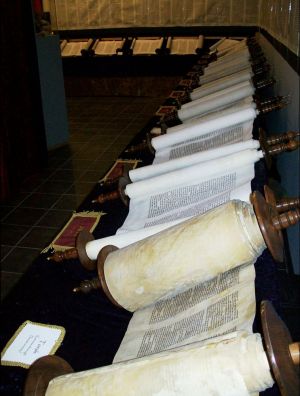

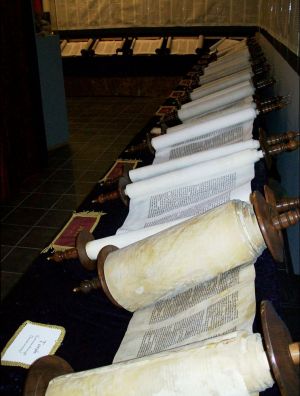

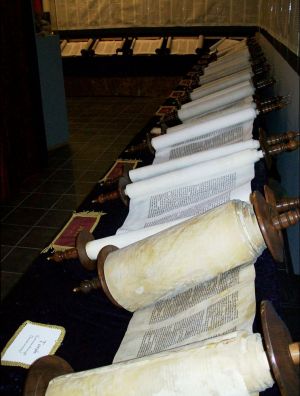

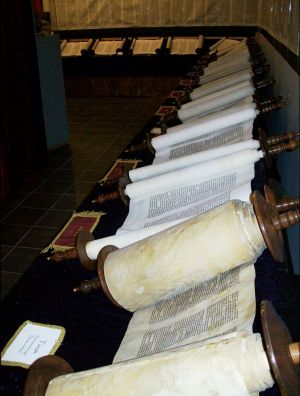

Being God's temple means that God dwells in us. The temple is God's dwelling place on earth. Before, the temple was made of stone, a house in the middle of the city of men. In Israel, there was only one temple, only one house of God, just as there was only one people of the Lord. One God, one people, one temple, one presence of God among the people.

"If anyone destroys God's temple, God will destroy him; for God's temple is holy, and you are that temple," says Paul. The Christian, therefore, must be the one who brings the living presence of God into the world. Those who see the Christian must feel that God dwells in him. But all this cannot happen unless the Christian is transformed into holiness, truth and charity.

How is the temple of God destroyed? There are several ways to destroy it. Here are a few.

The first way is to live a life that is different from that of Christ, when the body of Christ is made a body of sin and evil. Consider that Jesus Christ, in obedience to God, allowed himself to be nailed to the cross, exposing his body, the true temple of God, to every kind of suffering and deprivation. How can such a holy body be transformed by Christians into a body of sin, vice, and every other kind of evil? Either we believe that with Christ we are one body and that there can be no difference in holiness with Him, and then we truly change our way of life, or else the body of Christ, the temple of God, will be ruined. Sin destroys holiness in us, and by destroying it in us, it also diminishes it in the body of Christ, which then becomes ineffective in its witness and gift of salvation in the world.

The second way is to create an infinity of bodies of Christ, of temples in which we would like the Lord to live. This happens when each person does not build his faith on Christ, but pursues his own thoughts. That is, if you destroy brotherhood, you destroy fatherhood, you destroy yourself as a son: it is perdition. So it is not that I can say: I try to be good, but I am not interested in the community and others. No, because without others you destroy yourself, because you do not realise your true dimension, which is to be a child, that is, a brother. Whenever the body of Christ is damaged, the one who damages it is also damaged. It is only in the body of Christ that we have salvation. Those who place themselves outside the body of Christ also place themselves outside salvation.

So many who say (Luther docet) God yes and the Church no, it is serious! It is true destruction theorised as good.

These images of the building and the temple express what the Church is, which is the way in which it expresses our life as children, that is, brotherhood, and where each person expresses it in full freedom and responsibility for the gift they have received. The Church is a differentiated organism. What is the difference? It is something very important that must be mutually accepted, but with responsibility it must be put at the service of union and not division. Otherwise, I destroy myself.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse - exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All Generations Will Call Me Blessed

Catholics and Protestants Compared – In Defence of the Faith

The Church and Israel According to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(1Cor 10,1-6.10-12)

3rd Sunday in Lent (year C)

1Corinthians 10:1 For I do not want you to be ignorant, O brethren, that our fathers were all under the cloud, all crossed the sea,

1Corinthians 10:2 all were baptized in relation to Moses in the cloud and in the sea,

Paul, in this passage, refers us to the history of the past, to the lesson of history. He reminds us of the deeper meaning of history, which is the history of salvation. It is said that history is a teacher of life, but the pupils learn nothing. Paul instead says that from the history of Israel one must learn. The history of Israel is not just any history, but it is a way in which divine revelation was historically manifested. Revelation, in fact, was not manifested through the explanation of concepts, but through certain historical facts that are then also read and interpreted. The history of Israel is an exemplary history, so it is right and proper, if one wants to understand Jesus Christ, to see all the sacred history that prepares him. Among other things, this also accustoms us to reading our own little personal history, which is also salvation history because the Lord walks with us.

"For I do not want you to be ignorant": The Corinthians were supposed to know the facts narrated here, but the apostle wants them to know the typological significance that these facts have, and which is not to be ignored. Jesus Christ is the end result of a long journey, and we must know the journey that preceded it. Paul is very respectful of Israel's history and feels he must tell it. He refers us to these examples from the past that are extraordinary events, but they are also events of sin, and yet always instructive because they show what God's way is.

"Our fathers". Christians can consider the ancient Israelites as their fathers, because the Church succeeded the synagogue, and they are the true heirs and children of Abraham.

"They were all": Three times Paul repeats this expression. As if to say that salvation had been given to all. For all were led by the cloud, that is, by the presence of God, and all crossed the sea. All gained freedom from slavery and all were guided by God on the way to the promised land. Hence, on God's part, no exclusion, no preference towards some at the expense of others. He brought all his people out of Egypt, for all he parted the sea, for all he willed the cloud. All were in the condition of grace and truth that would enable them to conquer the promised land and possess it forever.

This universality of grace and truth for Paul is akin to a baptism. There is an immersion also of the children of Israel, even though their baptism is merely a figure of that instituted by Jesus Christ. However, there is a true immersion of the Israelites in the sea and in the 'cloud' and this immersion for them is true salvation, true deliverance.

Israel lived under the cloud, that mysterious cloud that guided the Israelites through the desert and sheltered them from the sun: signifying the presence of God, the Shekinah. To be under the cloud is to be under God's protection. They crossed the sea and were baptised: the passage from the land of slavery, which is Egypt, to the promised land, takes place through the crossing of the Red Sea, and this is a baptism because it signifies the detachment from the slavery of Egypt, liberation and purification, and the journey to the promised land.

"To be of Moses". Moses, the mediator of the old covenant, was a figure of Jesus Christ, and the Israelites led by him to the promised land were a figure of the Christians led by Jesus Christ to heaven. Now, just as Christians through baptism are incorporated into Jesus Christ and made subject to him as their Lord, whose laws they are bound to observe, so for the Israelites the mysterious cloud and the crossing of the Red Sea were a kind of baptism, whereby they remained subject to Moses and obliged to observe his laws. From that moment on, the people were separated from Egypt forever and belonged to the God who liberated them and to the prophet-mediator whom God gave them as their leader.

The mysterious cloud, a perceptible sign of God's presence, and of the favour He bestowed on His people, was a figure of the Holy Spirit, who is given in the baptism of Jesus Christ, and similarly the dry-foot passage through the Red Sea and the consequent deliverance from the bondage of Pharaoh, were figures of our deliverance from the bondage of sin through the waters of baptism.

Having stated this truth, Paul reminds us that it is not enough to come out of Egypt to have the promised land. The going out is one thing, the conquest and possession of the land is another. Between going out and conquering the land, there is a whole desert to cross. For the Israelites, the desert lasted for forty years; for Christians it lasts their whole life.

With baptism we come out of the slavery of sin, with a life of perseverance striving to conquer the kingdom of heaven we walk towards the glorious resurrection that will take place on the last day.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Revelation - exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants compared - In defence of the faith

(Buyable on Amazon)

Ps 17 (18)

This monumental ode, which the title attributes to David, is a Te Deum of the king of Israel, it is his hymn of thanksgiving to God because he has been delivered from all his enemies and from the hand of Saul. David acknowledges that God alone was his Deliverer, his Saviour.

David begins with a profession of love (v. 2). He shouts to the world his love for the Lord. The word he uses is 'rāḥam', meaning to love very tenderly, as in the case of a mother's love. The Lord is his strength. David is weak as a man. With God, who is his strength, he is strong. It is God's strength that makes him strong. This truth applies to every man. Every man is weak, and remains so unless God becomes his strength.

God for David is everything (v.3). The Lord for David is rock, fortress. He is his Deliverer. He is the rock in which he takes refuge. He is the shield that defends him from the enemy. The Lord is his mighty salvation and his bulwark. The Lord is simply his life, his protection, his defence. It is a true declaration of love and truth.

David's salvation is from the Lord (v. 4). It is not from his worthiness. The Lord is worthy of praise. God cannot but be praised. He does everything well. It is enough for David to call upon the Lord and he will be saved from his enemies. Always the Lord answers when David calls upon him. David's salvation is from his prayer, from his invocation.

Then David describes from what dangers the Lord delivered him. He was surrounded by billows of death, like a drowning man swept away by waves. He was overwhelmed by raging torrents. From these things no one can free himself. From these things only the Lord delivers and saves.

David's winning weapon is faith that is transformed into heartfelt prayer to be raised to the Lord, because only the Lord could help him, and it is to Him that David cries out in his distress. This is what David does: in his distress, he does not lose himself, he does not lose his faith, he remains whole. He turns his faith into prayer. He invokes the Lord. He cries out to Him. He asks Him for help and succour. God hears David's voice, hears it from his temple. His cry reaches him.

God becomes angry because He sees His elect in danger. The Lord's anger produces an upheaval of the whole earth. The earth trembles and shakes. The foundations of the mountains shake. It is as if a mighty earthquake turned the globe upside down. The spiritual fact is translated into such a profound upheaval of nature that one has the impression that creation itself is about to cease to exist. In this catastrophe that strikes terror, the righteous is rescued.

The Lord frees David because he loves him. Here is the secret of the answer to the prayer: the Lord loves David (v. 20). The Lord loves David because David loves the Lord. Prayer is a relationship of love between man and God. David invokes God's love. God's love responds and draws him to safety.

"Wholesome have I been with him, and I have guarded myself from guilt" (v. 24). David's conscience testifies for him. David prayed with an upright conscience, with a pure heart. This he says not only to God, but to every man. Everyone must know that the righteous is truly righteous. The world must know the integrity of God's children. We have a duty to confess it. It is on integrity that truly human relationships can be built. Without integrity, every relationship is tightened on falsehood and lies.

"The way of God is straight, the word of the Lord is tried by fire" (v. 31). What is the secret because God is with David? It is David's abiding in the Word of God. David has a certainty: the way indicated by the Word of God is straight. One only has to follow it. This certainty is lacking in the hearts of many today. Many do not believe in the purity of God's Word. Many think that it is now outdated. Modernity cannot stand under the Word of God.

"For who is God, if not the Lord? Or who is rock, if not our God?" Now David professes his faith in the Lord for all to know. Is there any other God but the Lord? God alone is the Lord. God alone is the rock of salvation. To seek another God is idolatry. This profession of faith must always be made aloud (remember the 'Creed'). Convinced people are needed. A faith hidden in the heart is dead. A seed placed in the ground springs up and reveals the nature of the tree. Faith that is in the heart must sprout up and reveal its nature of truth, holiness, righteousness, love and hope. A faith that does not reveal its nature is dead. It is a useless faith.

"He grants his king great victories; he shows himself faithful to his anointed, to David and his seed for ever" (v. 51). In this Psalm, David sees himself as the work of God's hands. That is why he blesses him, praises him, magnifies him. God's faithfulness and great favours for David do not end with David. God's faithfulness is for all his descendants. We know that David's descendants are Jesus Christ. With Jesus God is faithful for ever. With the other descendants, God will be faithful if they are faithful to Jesus Christ.

Here, then, the figure of David disappears to make way for that of the perfect king in whom the saving action that God offers the world is concentrated. In the light of this reinterpretation, the ode entered the Christian liturgy as a victory song of Christ, the 'son of David', over the forces of evil and as a hymn of the salvation he offered.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Revelation - exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants compared - In defence of the faith

(Buyable on Amazon)

Path of Lent, learning a little more how to “ascend” with prayer and listen to Jesus and to “descend” with brotherly love, proclaiming Jesus (Pope Francis)

Itinerario della Quaresima, imparando un po’ di più a “salire” con la preghiera e ascoltare Gesù e a “scendere” con la carità fraterna, annunciando Gesù (Papa Francesco)

Anyone who welcomes the Lord into his life and loves him with all his heart is capable of a new beginning. He succeeds in doing God’s will: to bring about a new form of existence enlivened by love and destined for eternity (Pope Benedict)

Chi accoglie il Signore nella propria vita e lo ama con tutto il cuore è capace di un nuovo inizio. Riesce a compiere la volontà di Dio: realizzare una nuova forma di esistenza animata dall’amore e destinata all’eternità (Papa Benedetto)

You ought not, however, to be satisfied merely with knocking and seeking: to understand the things of God, what is absolutely necessary is oratio. For this reason, the Saviour told us not only: ‘Seek and you will find’, and ‘Knock and it shall be opened to you’, but also added, ‘Ask and you shall receive’ [Verbum Domini n.86; cit. Origen, Letter to Gregory]

Non ti devi però accontentare di bussare e di cercare: per comprendere le cose di Dio ti è assolutamente necessaria l’oratio. Proprio per esortarci ad essa il Salvatore ci ha detto non soltanto: “Cercate e troverete”, e “Bussate e vi sarà aperto”, ma ha aggiunto: “Chiedete e riceverete” [Verbum Domini n.86; cit. Origene, Lettera a Gregorio]

In the crucified Jesus, a kind of transformation and concentration of the signs occurs: he himself is the “sign of God” (John Paul II)

In Gesù crocifisso avviene come una trasformazione e concentrazione dei segni: è Lui stesso il "segno di Dio" (Giovanni Paolo II)

Only through Christ can we converse with God the Father as children, otherwise it is not possible, but in communion with the Son we can also say, as he did, “Abba”. In communion with Christ we can know God as our true Father. For this reason Christian prayer consists in looking constantly at Christ and in an ever new way, speaking to him, being with him in silence, listening to him, acting and suffering with him (Pope Benedict)

Solo in Cristo possiamo dialogare con Dio Padre come figli, altrimenti non è possibile, ma in comunione col Figlio possiamo anche dire noi come ha detto Lui: «Abbà». In comunione con Cristo possiamo conoscere Dio come Padre vero. Per questo la preghiera cristiana consiste nel guardare costantemente e in maniera sempre nuova a Cristo, parlare con Lui, stare in silenzio con Lui, ascoltarlo, agire e soffrire con Lui (Papa Benedetto)

In today’s Gospel passage, Jesus identifies himself not only with the king-shepherd, but also with the lost sheep, we can speak of a “double identity”: the king-shepherd, Jesus identifies also with the sheep: that is, with the least and most needy of his brothers and sisters […] And let us return home only with this phrase: “I was present there. Thank you!”. Or: “You forgot about me” (Pope Francis)

Nella pagina evangelica di oggi, Gesù si identifica non solo col re-pastore, ma anche con le pecore perdute. Potremmo parlare come di una “doppia identità”: il re-pastore, Gesù, si identifica anche con le pecore, cioè con i fratelli più piccoli e bisognosi […] E torniamo a casa soltanto con questa frase: “Io ero presente lì. Grazie!” oppure: “Ti sei scordato di me” (Papa Francesco)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.