don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Aurora source’ spirituality, and origin’ sin

In the Annunciation

(Gen 3:9-15.20; Lk 1:26-38)

A great theologian of the Mystical Body wrote: «At dawn there is a wonderful moment: the one that immediately precedes the sunrise [...] the light has been growing, slowly at the beginning, then faster» (É. Mersch).

The ecclesial Faith announces and transmits in Mary ‘Most Holy’ a specific style, a Faith and Hope well denoted in Scripture.

She prorupting and freed, not alienated; independent of “night”, not embarrassed.

Capable of passing from the God of fathers to the Father. Son’s God.

Dawn after dawn, story after story, genesis after genesis, moving house after moving, she lived decisively a kind of ‘spirituality of the rising dawn’. And confidence over time.

When a question mark was coming, she realized it was time to ask herself and give answers.

She sensed the Opportunity to rise again: all Fruitful and without losing motivation, thanks to a paradoxical Alliance, with the limits and emotional burdens.

When a labor broke in, she understood that those waves invaded life not to destroy, but to move a sea of reflows, perhaps still too calm.

She didn’t dream of stemting or blocking that tide. She internalized the restlessness of doubts as a great moment of life.

A Happiness that came from innovation. Like a Presence.

Instead of feeling constrained, she paused on every case, to ask herself: «What do I still have to learn, from this?».

Perhaps she understood that inside her usual figure there was a woman capable of transgression - in the sense of feeling called to overturn all the ancient and artificial that didn’t correspond to her.

This is how she began, by accepting the Invitation: by housing in herself and give space to an unnameable Eternal, believed to be absolutely transcendent and never to be mixed with the flesh!

Not just a sacrilege, but heresy. Yet in the Mother of God the paradoxical heterodoxy comes as it were swept beyond.

His spirituality was cleared of the real great "stain": the inability to correspond to the personal Announcement.

«Too bad! Such a pity» «Sin! What a shame!» - it is precisely said of a lost opportunity: it’s the decrease of Uniqueness that we are in.

Pearl that every day could yield its uniqueness to the normalizing and sliced outline of common opinion, narrowing the space, the vital wave.

The divine call of every moment directed elsewhere Mary’s dreams and her innate knowledge - antechamber of trust.

In the Covenant of Root and Seed, decisions were not and did not remain poor: without brain burdens the Mother of God went directly to new possibilities, and to the end.

In this form she lived and weaved a sort of «spirituality of the rising sun». Recall of every moment, in the joy of changing herself and things; or in the happiness of living them like this - even by leaving everything.

While growing up, she did not age of uncertainties, because she tuned her destiny forward - saying Yes to what it faced - and instinctively even today we consider her Young.

She knew how to be with the contradictions of the environment subject to the ancient devotion, and with the unexpected waves, as with the eccentricity of the Son.

Mary cared for Him by being ‘present’, in simple everyday gestures. She relied only on the happy energy that surfaced all moments, and inhabited her.

She immersed herself in the minimal expressions of gestures with her gaze on the now, for a clear action.

Inadequate to the miracle but herself, while working thoroughly, she did not squeeze to the bone, like a torn-up person on her last legs - because she was able to get back into play. This is why she knew the dialogue with the most feared and suffered feeling: loneliness.

But even in the dark she regenerated, welcoming and coming out of it by strengthening the germs of change - feeding in the soul a sort of magical garden.

Always off track, the Immaculate has overcome all prejudices.

[Immaculate Conception, December 8]

Spirituality of Aurora source, and the sin of origin

In the Annunciation

(Gen 3:9-15.20; Lk 1:26-38)

A great theologian of the Mystical Body wrote: "At dawn there is a stupendous moment: that which immediately precedes the rising of the sun [...] the light has been growing, slowly at first, then more quickly" (É. Mersch, vol.I).

The ecclesial Faith announces and transmits in the all holy Mary a specific style, Faith and Hope, well denoted in Scripture.

Prorompent and enfranchised, not alienated; independent of 'night', not embarrassed.

Able to move from the God of the fathers to the Father. God of the Son.

The reassuring tradition of the feeble, almost dreamy Mother has its own considerable strength - it must be admitted: the intention to represent the nobility of a creature in balance.

Yet in the Gospels she is characterised by a surprising emancipation.

Even so, Mary remains an icon of the praying and authentic People, of the soul bride, of the friendly Church.

Relational, generous person and community, qualified by a dignity in the Spirit that is not exclusive, but at hand, personalising.

Dawn after dawn, affair after affair, genesis after genesis, move after move, he lived decisively - instant by instant - a kind of 'spirituality of the dawning dawn'. And trust in time.

This was his veracious and reflective (rather than withdrawn and pensive) foothold.

Despite the alarms, toils and dangers, strangely for us, she did not develop a sense of emptiness, nor did she allow herself to be conditioned or appalled by the perception of being watched and judged.

When a question mark came, she understood that it was time to ask and give answers.

She sensed the Opportunity to rise again: all Blind and without losing motivation, thanks to a paradoxical Alliance with emotional limits and burdens.

When labour broke through, she understood that those waves invaded life not to destroy, but to stir up a sea of ebbs that was perhaps still too calm.

In this way, she overlooked both the issues and the stasis: they would anchor her to the usual form of being and thinking - to the rushed, identified world, without imagination (and therefore more insecure).

She did not dream of stemming or blocking the tide, the Newness, the vital energy of Providence, even though the Calling by Name burst forth in a violent manner. To raise it to a new Easter.

She internalised the restlessness of doubts as a great moment of life, an incarnated Call that reminded her that there is Other.

She read her anxieties, welcoming and interpreting them, in order to overcome them.

In such an approach to events, the Virgin regenerated - and within her a subtle joy arose; that of the all beautiful dawn that rises.

First glow of a rising sun.

A Happiness hers that came from innovation. Like a Presence.

Secret side that makes creatures' lives take off, and fly over the issues that bridle the soul.

Instead of feeling constrained, she paused over each case, to ask herself: "What more do I have to learn, from this?".

In this way she was able to focus her days not on projects, but on the qualities and predispositions, even of family members - spending them well.

Perhaps she understood that within her usual figure was a woman capable of religious transgression - in the sense of feeling called to overturn all the old and artificial that did not correspond to her.

So she began, accepting the Invitation: to house within herself and give space to an Eternal then imagined unnameable, believed to be absolutely transcendent and that would never mix with the flesh!

Not just a sacrilege, but total heresy. But in the Mother of God the paradoxical heterodoxy [all our own and horizontal] is as if swept aside.

Her spirituality was cleared of the truly great 'stain': the inability to correspond to the personal Annunciation.

"Sin" - it is said of a missed opportunity: it is the flexing of the Oneness that we are within.

A pearl that every day can surrender its exceptionality to the normalising and slicing contour of common opinion, shrinking the space, the vital wave.

The divine call of each moment directed Mary's dreams and her innate knowledge elsewhere - the antechamber of trust.

In the Covenant of Root and Seed, decisions were not and did not remain poor: without cerebral burdens, the Mother of God went directly to new possibilities, and to the end.

In this Form she lived and wove a kind of "spirituality of the rising sun". She called for every moment, in the joy of changing herself and things; that is, in the happiness of living them that way - even of leaving everything behind.

Even as she grew up, she did not grow old with uncertainties, because she tuned her destiny forward - saying Yes to whatever came her way - and instinctively, even today, we consider her Young.

She knew how to be with the contradictions of the environment subject to the ancient devotion, and with the unexpected storms, as with the eccentricity of her Son.

He cared for it by being 'present', in simple everyday gestures. He relied only on the happy energy that surfaced every moment, and inhabited it.

She immersed herself in the minimal expressions of gestures with her gaze on the now, for clear action.

Inadequate to the miracle but herself, occupying herself did not exhaust - because she was capable of putting herself back into play. That is why she knew the dialogue with the most feared and suffered feeling: loneliness.

But even in the darkness she regenerated, welcoming it and coming out of it reinforcing the germs of change - nurturing a kind of magic garden in the soul.

Always off the rails, Immaculata overcame all prejudices.

Annunciation: how to enter the realm of the soul

From Religion to Faith, from barren to Beloved

The solemnity of the moment that restores the soul to the Mystery invites a wave upon wave: from the religion of the Temple to the domestic and personal Faith.

From the outside to within ourselves. From the models to the prophecy of the innate. Unique promise, more subtle condition.

Faith-faith - that of Mother - which shows the freedom and beauty of the new orientations, in the progression of the inner image-guides.

Covenant no longer for what is already known.

Her Covenant is all in the Openness to the Inexplicable that inhabits us. Intimate Eternal, which can now concretise the hope and journey of peoples. A turning point of authenticity, growing.

If the virgins of the heart make no demands, the Calling by Name (from our own fibres) uncovers the incapable and barren soul.

Ad coeli Reginam: Silent Echo... such an invisible nucleus-Vocation makes one wince. And with spontaneous virtue introduces the spirit into the fruitful synergy of God himself.

Spousal trust that reknots the threads of Salvation history: and contrasts with the broad road of alliances with people 'who matter'.

In the interweaving of the fruitful Initiative and our welcoming into our bosom, the Handmaid is an icon of each one's waiting and journey - where what remains decisive is not the usual, predictable desire.

A vibrant call that is prolonged in history, in a kind of unfolded and continuous Incarnation, thanks to the collaboration of distant, shaky and insignificant servants, like Mary.

Also ours, despite still being filled with normal expectations.

To internalise and live the message:

Which Words open us up to life in the Spirit and challenge the expected path?

What is our still in-between, unencountered zone?

How to realise the invisible Seed

Says the Tao Tê Ching (LXI): "The great realm that is held below, is the confluence of the world; it is the female of the world. The female always conquers the male with stillness, for she cheerfully submits to it. Therefore, the great realm that is below the little realm, attracts the little realm; the little realm that is below the great realm, attracts the great realm: the one lowers to attract, the other attracts because it is low. Let not the great kingdom exceed, lusting to feed and to unite others; let not the small kingdom exceed, lusting to be accepted and to serve others. That each one may obtain what he covets, the great should keep low.

On account of the mission, fixed Goal of eternal Counsel

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

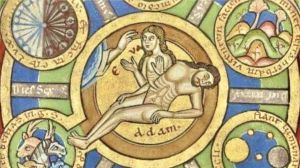

Today, we celebrate one of the most beautiful and popular feasts of the Blessed Virgin: the Immaculate Conception. Not only did Mary commit no sin, but she was also preserved from original sin, the common legacy of the human race. This is due to the mission for which God had destined her from eternity: to be the Mother of the Redeemer. All this is contained in the truth of faith of the "Immaculate Conception".

The biblical foundation of this Dogma is found in the words the Angel addressed to the young girl of Nazareth: "Hail, full of grace! The Lord is with you!" (Lk 1: 28). "Full of grace" - in the original Greek, kecharitoméne - is Mary's most beautiful name, the name God himself gave to her to indicate that she has always been and will always be the beloved, the elect, the one chosen to welcome the most precious gift, Jesus: "the incarnate love of God" (Deus Caritas Est, n. 12). We might ask: why exactly did God choose from among all women Mary of Nazareth? The answer is hidden in the unfathomable mystery of the divine will.

There is one reason, however, which is highlighted in the Gospel: her humility. Dante Alighieri clearly emphasizes this in the last Hymn of Paradise: "Virgin Mother, daughter of your Son, lowly and exalted more than any creature, the fixed goal of eternal counsel..." (Paradise, XXXIII, 1-3). In the Magnificat, her canticle of praise, the Virgin herself says: "My soul magnifies the Lord... because he looked upon his servant in her lowliness" (Lk 1: 46, 48).

Yes, God was attracted by the humility of Mary, who found favour in his eyes (cf. Lk 1: 30). She thus became the Mother of God, the image and model of the Church, chosen among the peoples to receive the Lord's blessing and communicate it to the entire human family.

This "blessing" is none other than Jesus Christ. He is the Source of the grace which filled Mary from the very first moment of her existence. She welcomed Jesus with faith and gave him to the world with love. This is also our vocation and our mission, the vocation and mission of the Church: to welcome Christ into our lives and give him to the world, so "that the world might be saved through him" (Jn 3: 17).

Dear brothers and sisters, may today's Feast of the Immaculate Conception illuminate like a beacon the Advent Season, which is a time of vigilant and confident waiting for the Saviour. While we advance towards God who comes, let us look at Mary, who "shines forth..., a sign of certain hope and comfort to the pilgrim People of God" (Lumen Gentium, n. 68).

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 8 December 2006]

Total assent of mind and heart

1. Today we are celebrating the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a feast very dear to the Christian people. It fits in well with the Advent season and radiates the purest light on our spiritual journey to Christmas.

Today we contemplate the humble girl of Nazareth who, by an extraordinary and ineffable privilege, was preserved from the contagion of original sin and from every fault, so that she could be a worthy dwelling-place for the Incarnate Word. In Mary, the New Eve, Mother of the New Adam, the Father's original, wondrous plan of love was re-established in an even more wondrous way. Therefore the Church gratefully acclaims: "Through you, immaculate Virgin, the life we had lost was returned to us. You received a child from heaven, and brought forth to the world a Saviour" (Liturgy of the Hours, Memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturday, Benedictus Antiphon).

2. Today's liturgy once again presents the Gospel account of the Annunciation. In response to the Angel, the Virgin proclaims: "Behold I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word" (Lk 1: 38). Mary expresses her total assent of mind and heart to God's hidden will and prepares herself to receive the Son of God, first in faith and then in her virginal womb.

"Behold!". Her prompt compliance with the divine will is a model for all of us believers, so that in great events, as well as in ordinary affairs, we will entrust ourselves entirely to the Lord.

By the witness of her life, Mary encourages us to believe in the fulfilment of God's promises. She calls us back to the spirit of humility, the right interior attitude of the creature towards the Creator; she urges us to put our sure hope in Christ, who fulfils the divine plan, even when events seem obscure and are difficult to accept. As a shining Star, Mary guides our steps to the Lord who comes.

3. Dear brothers and sisters! Let us turn our eyes to the Immaculate, all Holy and all Fair. May Mary, our Advocate, Mother of the "King of Peace", who crushes the serpent's head, help us, the men and women of the third millennium, to resist the seductions of evil; may she rekindle faith, hope and charity in our hearts, so that, faithful to our call and ready to make any sacrifice, we may be fearless witnesses to Jesus Christ, the Holy Door of eternal salvation.

[Pope John Paul II, Angelus 8 December 2000]

But to be filled we must make room, without complacency

Today we celebrate the solemnity of Mary Immaculate, which takes place within the context of Advent, a time of expectation: God will accomplish what he promised. But on today’s feast day we are told that something has already been accomplished, in the person and the life of the Virgin Mary. Today we consider the beginning of this fulfilment, which is even before the birth of the Mother of the Lord. In fact, her immaculate conception leads us to that precise moment when Mary’s life began to palpitate in her mother’s womb: already there was the sanctifying love of God, preserving her from the contagion of evil that is the common inheritance of the human family.

In today’s Gospel the Angel’s greeting to Mary resounds: “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with you!” (Lk 1:28). God has always thought of her and wanted her in his inscrutable plan, to be a creature full of grace, that is, full of his love. Yet, in order to be filled it is necessary to make room, to empty oneself, to step aside. Just as Mary did, she who knew how to listen to the Word of God and trust totally in his will, accepting it unreservedly in her own life. So much so that the Word became flesh in her. This was possible thanks to her “yes”. To the Angel who asks her to be ready to become the mother of Jesus, Mary replies: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word” (v. 38).

Mary does not lose herself in reasoning, she does not place obstacles in the Lord’s way, but she promptly entrusts herself and makes room for the action of the Holy Spirit. She immediately makes her whole being and her personal history available to God, so that the Word and the will of God may shape and bring them to fulfilment. Perfectly corresponding to God’s plan for her, Mary then becomes the “all beautiful”, the “all holy”, but without the slightest shadow of complacency. She is humble. She is a masterpiece, whilst remaining humble, small, poor. In her is reflected the beauty of God which is all love, grace, gift of self.

I would also like to underline the word with which Mary defines herself in her surrender to God: she professes herself “the handmaid of the Lord”. Mary’s “yes” to God takes on from the beginning the attitude of service, of attention to the needs of others. The visit to Elizabeth which immediately follows the Annunciation testifies this concretely. One’s availability to God is found in one’s willingness to take on the needs of one’s neighbour. All of this without clamour and ostentation, without seeking places of honour, without advertising, because charity and works of mercy needn’t be exhibited as a trophy. Works of mercy are done in silence, in secrecy, without boasting of doing them. Even in our communities, we are called to follow the example of Mary, practicing the style of discretion and concealment.

May the feast of our Mother help us to make our whole life a “yes” to God, a “yes” made of adoration of him and of daily gestures of love and service.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 8 December 2019]

Immaculate Conception: Personalism made safe

Conversion, Fightback

(Is 11:1-10; Mt 3:1-12)

The Son of God who Comes «will not judge according to appearances and will not make decisions by hearsay» (Is. 11:3).

Thus the Church who bears witness to him.

But how is it possible in the society of the outside, not to be conditioned by dominant opinions?

Not by trying to reproduce the world around.

But attempting the principle of a renewal that can only be introduced from the Source of the Sense of self and the cosmos - then it will also flow out, and it will happen constantly.

Not... immediately with blush, plump lips, swollen cheekbones, leveling of furrows; nor with an overambitious "U-conversion".

Not a defibrating regression to external religion; rather, by settling inside, in that Force of the Logos in the heart.

So, in the Gospels the Greek term «metanoia» doesn’t indicate a return to the God of normalized worship; rather, a change of mentality.

The life of Faith is precisely marked by the reversal of the hierarchy of values, which is reflected in real choices.

New Testament Conversion is a reappropriation of himself, not as in devotions, but with a coup de main.

A leap forward which makes fruitful, green and happy the recovery of the whole Church that draws from its own Source.

A reconquest of the same Core that drags the whole reality.

God in the soul not only improves, but rises in Vital Fullness. He acts by refounding, and chisels our true Path.

First of all He flies over the established cliques. It would be useless to insist on environments and characters refractory to the novelty of the Spirit.

Thus, the Word-event goes to land on a visionary of the present and the future.

At less than twenty years old, John should have presented himself to the practitioners of the rite and the Law to be examined according to the purist norms of the Torah, in order to then officiate the cults at the Temple in Jerusalem.

But despite being of a priestly lineage, he rejected that formal, insensitive and corrupt environment - which he knew well.

In short, the choice and the figure of the Baptist is a Reminder for us: to the authentic Church it’s not enough to iron wrinkles.

Botulinum and creams do not scratch reality, but disturb the Essence.

The Prophet felt young and alive precisely because he had not wanted to resemble, match at all costs, be identifiable, repeat opinions - nor did he limit himself to a remediation of the situation.

He didn't want to die out. He wanted to stare his gaze not on the big signs, but at his own (and others’) attitudes.

For us too, the "destiny" that belongs to us lurks in that daily impetus to want to do something creative and personal, unpublished and drawn only from the Core of our waves, rippling, many faces.

Advent [the Coming] thus proposes to us that Call of the Roots which opens the way - so that we may achieve something that is not habitual, but belongs to us.

We will be «shoots that sprout» not slumped, on the contrary that «rise to banner for the multitudes» because kidnapped and placed on this Ray of unusual «knowledge of the Lord that will fill the earth».

Counter-exodus of John the Baptist, counter-exodus of Jesus

Retracing the crossing of the Jordan.

Epistrèphein: Conversion is, in the ancient mindset, 'turning around', 'going back' (Hebrew Shùb) [because the people have strayed from God, from the Temple, from the Fathers].

In the Second Testament, the term is only Metanoein:

For the Baptist, conversion [already in the sphere of «metanoein»] does not have a specifically religious, liturgical or doctrinal meaning, but rather an existential one: it means, for example, putting an end to social injustices.

But according to Jesus' new preaching, Conversion has a broader and more central meaning. Christ proposes a new vision of God himself, of his Heart - and therefore of authentic man and society.

While the «brood of vipers' continues to inject its venom... here instead is the «Beautiful Fruit», complete and full, of this new tree (v. 10).

The CEI '74 translation proposed “good fruits” [which has another meaning, linked to morality, simplistic]. Now it is “good fruit”, which is perhaps halfway there.

«Beautiful Fruit» is Love; the product of the Fire of the Spirit [Gal 5:22: love, joy, peace, magnanimity, benevolence, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control].

This Fire is no longer an external element. No longer an extrinsic power. It comes from within.

Like the Action of the new Waters, now Joyful, which are assimilated not for the purpose of cleansing and purifying, but for growth.

A Flame yes, that burns away all evil - without, of course, making a «clean sweep».

Not spiritual life: Life in the Spirit!

A completely different specific weight, a completely different Breath.

Counter-exodus of the Baptist: sometimes we stopped there.

Counter-exodus of Jesus: Life in the Spirit.

[2nd Advent Sunday (year A), December 7, 2025]

Convert? Overturn!

(Is 11:1-10; Mt 3:1-12)

The Son of God who is coming "will not judge by appearances, nor make decisions based on hearsay" (Is 11:3).

So does the Church that bears witness to him.

But how can we, in the outside world, avoid being influenced by prevailing opinions?

How can a withered reality blossom again and reveal its splendour, manifesting its divine nature?

Certainly not by striving to remain young and beautified.

Not by trying to reproduce the world around us.

Rather, by attempting the principle of renewal that can only be introduced from the Source of the Sense of self and of the cosmos - then it will also flow outwards, and it will happen constantly.

Not... immediately with blush, pouty lips, inflated cheekbones, levelling of furrows; nor with a wishful 'U-turn'.

Not an exhausting regression to the external religion of the Temple; rather, settling within, in that Force of the Logos in the heart.

In this way, in the Gospels, the Greek term 'metanoia' does not indicate a return to the God of normalised worship; rather, a change of mentality.

The life of Faith is precisely marked by the reversal of the hierarchy of values, which is reflected in real choices.

New Testament conversion is a reappropriation of oneself, but not as in devotions, rather with a coup de main.

A leap forward that makes the recovery of the whole Church, which draws from its own Source, fruitful, green and happy.

A reconquest of the same Core that draws the whole of reality along with it.

God in the soul not only improves, but rises again in vital fullness.

The Lord does not repackage the contents, dressing them up with superficial updates; he intervenes by creating.

He acts by refounding, and chisels out our true Path.

First of all, he overlooks the established cliques of the greats of the world and of the sacred.

It would be useless to insist on environments and personalities that are constitutionally resistant to the newness of the Spirit.

Even then, it was harmful to continue to be used as a screen by a caste that, after the Exodus, had seized and taken God and his things hostage, content to live off their income.

Thus, the Word-event comes to rest on a visionary of the present and the future.

At less than twenty years of age, John should have presented himself to the professionals of ritual and the Law to be examined according to the purist norms of the Torah, in order to then officiate the cults at the Temple in Jerusalem.

But despite being of priestly lineage, he rejected that formal, insensitive and corrupt environment - which he knew well.

In short, the choice and figure of the Baptist is a reminder for us: it is not enough for the authentic Church to smooth out the wrinkles.

Botox and creams do not scratch reality, but they disturb the Essence.

Our primordial Source offers us opportunities and even uncertainties, so that we can make the most of our abilities.

It makes harsh reminders, revealing varied situations; even embarrassing events, together with ideal impulses.

Along the way, we will find ways to activate the primal energy of our eternal side, learning to recognise the novelties from Elsewhere that want to make space for themselves in the folds of history and in us.

So every day, behaviour can change: for example, I can imagine an initiative to be carried out and it is as if I were returning to that Fire that does not go out inside me - to welcome renewed vigour, a broader view and another magical breath.

The Baptist felt young and alive precisely because he did not want to resemble others, to fit in at all costs, to be identifiable, to repeat opinions - nor did he limit himself to remedying the situation.

He understands that forgiveness of sins is obtained simply by changing one's life [vv.6ff]; not by performing a liturgy in the Temple!

He did not want to fade away, purifying the institution - because he wanted to see the scope of reality beyond the sacred enclosure.

He wanted to fix his gaze not on the great signs, but on his own (and others') attitudes.

For us too, our 'destiny' lies in that daily impetus to want to do something creative and personal, something new and drawn only from the core of our waves, our tides, our many faces.

Advent [Coming] offers us once again that Call of the Roots that opens the way, throws open the toll booth - so that we can achieve something unusual, but which belongs to us.

Changing the order of things heals each of us with that different youthfulness that comes from the imbalance of appearances and conformist judgements.

A liveliness that does not come from the standard of commemorations.

Transparency deriving from breaking through peaceful patterns. Those that do not open up the adventure of a new path - one that can make us 'be born' not already seasoned, and fall in love.

Other than impromptu and sporadic adjustments, according to fashion and local external conditions!

We must learn to recognise and activate that spring-like aspect of ourselves that lives in God's Covenant.

A rainbow that nothing and no one will ever be able to pave over.

It towers above our disturbances and disturbers. And it runs, offering new paths that strengthen us - enabling us to think, imagine and live in this fundamental Eros.

In the refraction of explorations, our muddy earth is bound to Heaven; at first episodically or confusingly, but spontaneously and immediately colourfully.

The Path of entrusting ourselves to the varied springs of Being - to the Self still hidden - will be the paradoxical platform that transmigrates our 'flesh' [cf. parallel Lk 3:6; Greek text], that is, our vulnerability as creatures like leaves in the wind or cracked and torn, in the event of a life saved.

We will be 'sprouting shoots' that are not crushed, but rather 'rise up as a banner for the multitudes' because we are enraptured and placed on that Ray of unusual 'knowledge of the Lord that will fill the earth'.

Almost without knowing it, no longer removed or absorbed by external influences. For a Coming One who still brings to life the hidden self without straitjackets, but rather in the change of alternating events.

A Sacred One who is not entrenched like the one who still blocks pastoral leadership - but who awakens us, not for a backward adjustment and continuation at all costs.

The Eternal bursts forth unexpectedly.

And reactivates us as in John, outside the established boundaries, thanks also to the chaos of patterns.

Making the Judgement manifest in today's deserts

Dear brothers and sisters!

Today, the Second Sunday of Advent, it presents to us the austere figure of the Precursor, whom the Evangelist Matthew introduces as follows: "In those days came John the Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judea: "Repent, for the Kingdom of heaven is at hand'" (Mt 3: 1-2). His mission was to prepare and clear the way for the Lord, calling the people of Israel to repent of their sins and to correct every injustice. John the Baptist, with demanding words, announced the imminent judgement: "Every tree, therefore, that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire" (Mt 3: 10). Above all, John put people on guard against the hypocrisy of those who felt safe merely because they belonged to the Chosen People: in God's eyes, he said, no one has reason to boast but must bear "fruit that befits repentance".

While the Advent journey continues, while we prepare to celebrate the Birth of Christ, John the Baptist's appeal for conversion rings out in our communities. It is a pressing invitation to open our hearts to receive the Son of God, who comes among us to make manifest the divine judgement. The Father, writes John the Evangelist, judges no one but has given all judgement to the Son because he is the Son of Man (cf. Jn 5: 22, 27). And it is today, in the present, that our future destiny is being played out. It is our actual conduct in this life that decides our eternal fate. At the end of our days on earth, at the moment of death, we will be evaluated on the basis of our likeness - or lack of it - to the Child who is about to be born in the poor grotto of Bethlehem, because he is the criterion of the measure that God has given to humanity. The Heavenly Father, who expressed his merciful love to us through the birth of his Only-Begotten Son, calls us to follow in his footsteps, making our existence, as he did, a gift of love. And the fruit of love is that fruit which "befits repentance", to which John the Baptist refers while he addresses cutting words to the Pharisees and Sadduccees among the crowds who had come for Baptism.

Through the Gospel, John the Baptist continues to speak down the centuries to every generation. His clear, harsh words are particularly salutary for us, men and women of our time, in which the way of living and perceiving Christmas unfortunately all too often suffers the effects of a materialistic mindset. The "voice" of the great prophet asks us to prepare the way of the Lord, who comes in the external and internal wildernesses of today, thirsting for the living water that is Christ. May the Virgin Mary guide us to true conversion of heart, so that we may make the necessary choices to harmonize our mentalities with the Gospel.

[Pope Benedict, Angelus, 9 December 2007]

Prepare the Way for the Lord

Dear brothers and sisters!

1. “Lord, you have searched me and you know me . . . You know all my ways” (Ps 139 [138]:1–2).

This is how we pray together with the psalmist in today's liturgy. His words express what unites us here deeply, invisibly, it is true, but truly and essentially: we are gathered here in our common faith in God who is present, in God who searches and knows us. God has always known everything about us, he knows each one of us, we are all inscribed in his loving heart, his Providence embraces the whole of creation. "For in him we live and move and have our being" (Acts 17:28): this is how the Apostle Paul explains to the Athenians, who questioned him in the Areopagus, God's closeness to us human beings.

We are gathered here before him – before the invisible God. In his eternal word, the incarnate Son, he has called us by name, so that we may have life through him and have it in abundance (Jn 10:10).

This is why we celebrate the Eucharist. We come to receive from the Father in Jesus Christ everything that can serve our salvation. And we bring everything: our joy, our gratitude, our prayers, ourselves, to give ourselves entirely to the Father in Christ: in him, who is the firstborn of all creation (cf. Col 1:15). In and through Christ, we want to pray to our creator and Father together with the psalmist: "I praise you, for you have made me as a wonder; your works are marvellous" (Ps 139 [138]:14).

3. "Lord, you search me and you know me." The Church repeats these words of the psalmist in today's festive liturgy, on the anniversary of the birth of John the Baptist, son of Zechariah and Elizabeth. "From his mother's womb" God called him to preach "the baptism of conversion" in the Jordan and to prepare for the coming of his Son (cf. Mk 1:4).

The particular circumstances of John's birth have been handed down to us by the evangelist Luke. According to an ancient tradition, it took place at Ain Karim, outside the gates of Jerusalem. The circumstances surrounding this birth were so unusual that even at that time people wondered, "What will this child be?" (Lk 1:66). For his believing parents, neighbours and relatives, it was clear that his birth was a sign from God. They saw clearly that the "hand of the Lord" was upon him. This was already evident in the announcement of his birth to his father Zechariah while he was serving as a priest in the temple in Jerusalem. His mother, Elizabeth, was advanced in years and was considered barren. Even the name "John" that was given to him was unusual for his environment. His father himself had to give orders that he be called "John" and not, as everyone else wanted, "Zachariah" (cf. Lk 1:59-63).

The name John means "God is merciful" in Hebrew. Thus, the name itself expresses the fact that the newborn would one day announce God's plan of salvation.

The future would fully confirm the predictions and events surrounding his birth: John, son of Zachariah and Elizabeth, became the "voice of one crying in the wilderness" (Matthew 3:3), who on the banks of the Jordan called the people to repentance and prepared the way for Christ.

Christ himself said of John the Baptist that "among those born of women there has arisen no one greater" (cf. Mt 11:11). For this reason, the Church has also reserved a special veneration for this great messenger of God from the very beginning. Today's feast is an expression of this veneration.

4. Dear brothers and sisters! This celebration, with its liturgical texts, invites us to reflect on the question of the becoming of man, his origins and his destiny. It is true that we seem to know a great deal about this subject, both from the long experience of humanity and from increasingly in-depth biomedical research. But it is the word of God that always re-establishes the essential dimension of the truth about man: man is created by God and wanted by God in his image and likeness. No purely human science can prove this truth. At most, it can approach this truth or intuitively suppose the truth about this 'unknown being' that is man from the moment of his conception in his mother's womb.

At the same time, however, we find ourselves witnessing how, in the name of a supposed science, man is "reduced" in a dramatic process and represented in a sad simplification; and so it happens that even those rights that are based on the dignity of his person, which distinguishes him from all other creatures in the visible world, are overshadowed. Those words in the book of Genesis, which speak of man as a creature made in the image and likeness of God, highlight, in a concise and at the same time profound way, the full truth about him.

5. We can also learn this truth about man from today's liturgy, in which the Church prays to God, the creator, with the words of the psalmist:

"Lord, you have searched me and you know me . . .

You created my inmost being

and knit me together in my mother's womb . . .

You know me through and through.

When I was being formed in secret . . .

my bones were not hidden from you . . .

I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made" (Ps 139 [138], 1, 13-15).

Man is therefore aware of what he is - of what he has been from the beginning, from his mother's womb. He knows that he is a creature whom God wants to meet and with whom he wants to dialogue. Moreover, in man he wants to meet the whole of creation.

For God, man is “someone”: unique and unrepeatable. He, as the Second Vatican Council says, “is the only creature on earth that God willed for its own sake” (cf. Gaudium et Spes, 24).

"The Lord called me from my mother's womb; from my mother's womb he named me" (Is 49:1); like the name of the child born in Ain-Karim: "John". Man is that being whom God calls by name. For God, he is the created “you.” Among all creatures, he is that personal “I” who can turn to God and call him by name. God wants man to be that partner who turns to him as his creator and Father: “You, my Lord and my God.” To the divine “you.”

6. Dear brothers and sisters! How do we human beings respond to this call from God? How does man today understand his life? In no other age have so many efforts been made through technology and medicine to protect human life against disease, to prolong it ever more and to save it from death. At the same time, however, no other era has produced so many places and methods of contempt and destruction of man as our own. The bitter experiences of our century with the death machines of two world wars, the persecution and destruction of entire groups of people because of their ethnic or religious affiliation, the arms race to the extreme limit, and the powerlessness of men in the face of great misery in many parts of the world could lead us to doubt, if not deny, God's affection and love for man and for the whole of creation.

Or should we rather ask ourselves the opposite question, when we consider the terrible events that have befallen the world because of human beings and in the face of the many threats of our time: is it not human beings who have distanced themselves from God, who is their origin, have they not strayed from him, and have they not elevated themselves to the centre and measure of their own lives? Do you not think that in the experiments conducted on human beings, experiments that contradict their dignity, in the mental attitude of many towards abortion and euthanasia, there is a worrying loss of respect for life? Is it not evident, even in your society, when you look at the lives of many - characterised by inner emptiness, fear and escape - that man himself has cut off his roots? Shouldn't sex, alcohol and drugs be seen as warning signs? Don't they indicate the great loneliness of modern man, a desire for care, a hunger for love that a world turned in on itself cannot satisfy?

In fact, when man is no longer connected to his roots, which is God, he becomes impoverished of inner values and gradually falls prey to various threats. History teaches us that men and peoples who believe they can exist without God are inevitably destined for the catastrophe of self-destruction. The poet Ernst Wiechert expressed this in the following sentence: "Be assured that no one will fall out of this world who has not first fallen out of God."

On the contrary, through a living relationship with God, man acquires an awareness of the uniqueness and value of his own life and personal conscience. In his concrete life, he knows that he is called, supported and encouraged by God. Despite injustices and personal suffering, he understands that his life is a gift; he is grateful for it and knows that he is responsible for it before God. In this way, God becomes a source of strength and trust for man, and from this source man can make his life worthy and also know how to put it generously at the service of his brothers and sisters.

7. God called John the Baptist already “in his mother’s womb” to be “the voice of one crying in the wilderness” and thus to prepare the way for his Son. In a very similar way, God has also “laid his hand” on each one of us. He has a special calling for each of us, and he entrusts each of us with a task that he has designed for us.

In each call, which can come to us in many different ways, we hear that divine voice which spoke through John: "Prepare the way of the Lord!" (Mt 3:3).

Every person should ask themselves how they can contribute, in their own work and in their own position, to opening the way for God in this world. Every time we open ourselves to God's call, we prepare, like John, the way of the Lord among people. Among all those men and women who throughout history have opened themselves in an exemplary way to God's work, I would like to mention St Martin. Even though centuries separate us from him, he is close to us in following Christ through his example and his ageless greatness. He is your diocesan and regional patron saint. He is venerated as the great saint of the entire region of Pannonia: 'Martinus natus Savariae in Pannonia'.

Martin stands before us as a man who trusted God, who understood and practised his 'yes to faith' as a 'yes to life'. He fulfilled what he felt called to do to the very end. Even before he became a Christian, he shared his cloak with the poor. Military life certainly gave him satisfaction, but it was not enough for him. Like every man, he was searching for lasting joy, a joy that nothing could destroy. Only in his later years did he encounter Jesus Christ in faith, and in him he found the fullness of joy and happiness. Through faith, Martin did not become poorer, but richer: he grew in his humanity, he grew in grace before God and men.

8. In order that this truth – that man finds his fulfilment and his true salvation only in God – may always be proclaimed, priests and religious are necessary. Therefore, be aware of your shared responsibility in awakening spiritual vocations. I was delighted to learn that in a few days six priests will be ordained in your diocese. This is a great gift for the Church and for your country. Never cease to pray that the Lord will send labourers into his harvest!

I address myself in a special way to young people, who are the future of your country and of the Church. Try to understand, dear young friends, what God wants from you. Be open to his call! Listen carefully, for he may be inviting you to follow Christ as priests or religious here in your homeland or in mission lands.

I pray to all of you: whatever path you decide to take, let the seed of God's Word fall into the furrows of your heart; once there, do not let it dry up, but nurture it so that it may sprout and bear rich fruit.

Say “yes to faith”, say “yes to life”, because God lives it together with you! Together with him, your life will become an adventure: it will be beautiful, rich and full!

10. “Prepare the way of the Lord . . . that he may bring my salvation to the ends of the earth” (cf. Is 49:6). When we, dear brothers and sisters, look at our vocation as Christians, who through Baptism have become one body with Christ, then these words of the Lord, spoken through the prophet Isaiah – from the advent of salvation history before the first coming of Christ – take on a special meaning for us at the end of the second millennium since the birth of Christ. We find ourselves, especially here in the old continent, in a “new advent” of universal history. Must we not ensure that the “salvation” given to us by Christ reaches once again the furthest frontiers of Europe?

We all feel a great need for renewal, for a new encounter with God. Renewal, conversion and encounter with God, at the sources of faith, meditation on integral faith: this is the appeal that today's feast of the birth of John the Baptist makes to us, and this is the spur that the example of St Martin also gives us.

We all know the need for renewal in our society, for the re-evangelisation of our continent: so that Europeans do not lose their sense of fundamental dignity; so that they do not become victims of the destructive forces of spiritual death, but rather have life, and have it in abundance (cf. Jn 10:10)!

Praised be Jesus and Mary!

[Pope John Paul II, homily at Eisenstadt-Trausdorf Airport, 24 June 1988]

The ability to be amazed at things around us promotes religious experience and makes the encounter with the Lord more fruitful. On the contrary, the inability to marvel makes us indifferent and widens the gap between the journey of faith and daily life (Pope Francis)

La capacità di stupirsi delle cose che ci circondano favorisce l’esperienza religiosa e rende fecondo l’incontro con il Signore. Al contrario, l’incapacità di stupirci rende indifferenti e allarga le distanze tra il cammino di fede e la vita di ogni giorno (Papa Francesco)

An ancient hermit says: “The Beatitudes are gifts of God and we must say a great ‘thank you’ to him for them and for the rewards that derive from them, namely the Kingdom of God in the century to come and consolation here; the fullness of every good and mercy on God’s part … once we have become images of Christ on earth” (Peter of Damascus) [Pope Benedict]

Afferma un antico eremita: «Le Beatitudini sono doni di Dio, e dobbiamo rendergli grandi grazie per esse e per le ricompense che ne derivano, cioè il Regno dei Cieli nel secolo futuro, la consolazione qui, la pienezza di ogni bene e misericordia da parte di Dio … una volta che si sia divenuti immagine del Cristo sulla terra» (Pietro di Damasco) [Papa Benedetto]

And quite often we too, beaten by the trials of life, have cried out to the Lord: “Why do you remain silent and do nothing for me?”. Especially when it seems we are sinking, because love or the project in which we had laid great hopes disappears (Pope Francis)

E tante volte anche noi, assaliti dalle prove della vita, abbiamo gridato al Signore: “Perché resti in silenzio e non fai nulla per me?”. Soprattutto quando ci sembra di affondare, perché l’amore o il progetto nel quale avevamo riposto grandi speranze svanisce (Papa Francesco)

The Kingdom of God grows here on earth, in the history of humanity, by virtue of an initial sowing, that is, of a foundation, which comes from God, and of a mysterious work of God himself, which continues to cultivate the Church down the centuries. The scythe of sacrifice is also present in God's action with regard to the Kingdom: the development of the Kingdom cannot be achieved without suffering (John Paul II)

Il Regno di Dio cresce qui sulla terra, nella storia dell’umanità, in virtù di una semina iniziale, cioè di una fondazione, che viene da Dio, e di un misterioso operare di Dio stesso, che continua a coltivare la Chiesa lungo i secoli. Nell’azione di Dio in ordine al Regno è presente anche la falce del sacrificio: lo sviluppo del Regno non si realizza senza sofferenza (Giovanni Paolo II)

For those who first heard Jesus, as for us, the symbol of light evokes the desire for truth and the thirst for the fullness of knowledge which are imprinted deep within every human being. When the light fades or vanishes altogether, we no longer see things as they really are. In the heart of the night we can feel frightened and insecure, and we impatiently await the coming of the light of dawn. Dear young people, it is up to you to be the watchmen of the morning (cf. Is 21:11-12) who announce the coming of the sun who is the Risen Christ! (John Paul II)

These two episodes — a healing and a resurrection — share one core: faith. The message is clear, and it can be summed up in one question: do we believe that Jesus can heal us and can raise us from the dead? The entire Gospel is written in the light of this faith: Jesus is risen, He has conquered death, and by his victory we too will rise again. This faith, which for the first Christians was sure, can tarnish and become uncertain… (Pope Francis)

These two episodes — a healing and a resurrection — share one core: faith. The message is clear, and it can be summed up in one question: do we believe that Jesus can heal us and can raise us from the dead? The entire Gospel is written in the light of this faith: Jesus is risen, He has conquered death, and by his victory we too will rise again. This faith, which for the first Christians was sure, can tarnish and become uncertain… (Pope Francis)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.