don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Rough life’s power

(Jn 1:1-18)

Gialal al-Din Rumi, mystic and lyric Persian of the thirteenth century, writes in his poem «The Inn»:

The human being is an Inn,

someone new is coming every morning.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

a few moment of awareness comes from time to time,

as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome everyone, spend time with all!

even if there is a crowd of sorrows

that devastates the house violently

stripping it of all the furniture,

likewise, treat each guest with honor:

it could be that he’s freeing you

in view of new pleasures.

To dark thoughts, to shame, to malice,

go meet on the door laughing,

and invite them in.

Be grateful for everything that comes,

because everything was sent

as a guide to the afterlife.

We recognize in this poem-emblem some keystones of discernment, underlying the existential paradoxes of the Incarnation theology.

A Sufi mystic helps to understand the supporting pillars of our Journey, better than many one-way evasive doctrines.

They are identical laws of the soul already expressed in the famous Prologue of the Fourth Gospel: raw life is filled with powers.

Incarnation: our most intimate fulcrums distinguish the adventure of Faith from the one-sided existence of the believer in God.

The experience of fullness in the world is launched from our own slums of the soul. As a Zen aphorism [collected in Ts'ai Ken T'an] suggests: «Too pure water has no fish».

Jn writes that the Logos became «flesh» in the Semitic meaning of a being full of limits, unfinished; for this reason voted to the relentless search of sense (partial until death).

The weakness of all of us is not redeemed by admiring a heroic model and imitating it off scale, but in a process of recovering the whole being and our history.

In short, there are no Gifts of the Spirit that do not pass through the human dimension.

Already here and now we thrive of a precious Word’ seed. His authentic Tent is in-us and in all the stimuli.

The more we manage to maximize our creatural and humanizing reality, the more we will be on the path towards the divine condition - rooted on earth of the priceless lineage generated by the Logos.

Wisely, we will not do it by becoming winners, but by hosting what comes from Providence, from people and emotions (even from inconvenience) without prejudice.

Not the Ten Words - a typical Semitic category - but the One inclusive Word (Dream and Sense of Creation) is at the foundation of the Father’s Work.

The Logos that takes root is qualitative, not partial, nor centred on a single name: One because Unitary.

Religions do not welcome all guests [they will prove to be much more fruitful than we imagine] knocking at the interior inn.

The story of Jesus of Nazareth suggests that sin has instead been torn apart, that is: imperfection is not an obstacle to communion with Heaven, but a spring.

Discomforts do not make us inadequate: they set us on the road.

The Lord has destroyed the feeling of insufficiency of carnal condition and the humiliation of the unbridgeable distances.

«Word» End on univocity.

To internalize and live the message:

How do you start your days? Welcome your guests (even the void)? Or do you face them with excess of judgment?

[December 31, seventh day between the Octave of Christmas]

Power of raw life

(Jn 1:1-18)

Gialal al-Din Rumi, a 13th century Persian mystic and lyricist (founder of the Sufi confraternity of dervishes) writes in his poem 'The Inn

The human being is an inn,

every morning someone new arrives.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

a moment of awareness arrives from time to time,

like an unexpected visitor.

Welcome them all, entertain them all!

Even if there is a crowd of sorrows

violently ravaging the house

stripping it of all furniture,

still, treat every guest with honour:

it may be that he is freeing you

in view of new pleasures.

To gloomy thoughts, to shame, to malice,

go to the door laughing,

and invite them in.

Be thankful for everything that comes,

for everything has been sent

as a guide to the hereafter.

We recognise in this poem-emblem some keys to discernment, underlying the existential paradoxes of the theology of the Incarnation.

A Sufi mystic helps to understand the pillars of our Path, far better than many evasive one-way doctrines.

They are identical laws of the soul already expressed in the famous Prologue of the Fourth Gospel: raw life is filled with powers.

Synthesis of underlying themes that specify Life in the Spirit in comparison to common religious experience.

Incarnation: our innermost fulcrums distinguish the adventure of Faith from the believer's one-sided existence in God.

Waking up in the morning, there is a new arrival in our 'inn' - not always overtly uplifting.

But in the many-roomed inn reception there must be a welcome, so that the unplanned encounter can open us up, become an aspect, or motive and engine of the decisive encounter - perhaps also unexpected.

Happenings, situations, insights, advice, relationships, even strange emotions, new realisations, other projects that we had not previously imagined or were simply unexpressed, come to visit us and leave us amazed.

Guests are to be welcomed, they have their dignity and they all express sides of ourselves: we are bound to welcome each one of them; even the anger, the sadness, the fears.

Missionaries know well that doubts are more fruitful than certainties, and that insecurity is safer than all 'certainties'.

The crowd of guests can call into question what is in our dwelling or inn, and sweep away all or part of it - even the foundations.

By being patient enough to honour each tenant - be they ancient memories or scapegoating utopias - we prepare our souls for an experience of fullness of being, launched from our own slums (muck become sprout territory).

Beginning with respect for our different boundaries and because of them, each new or re-emerging presence focuses us on listening to all the chaos that we are - chaos that prepares the delights that belong to us, and only in this way engage.

Our eternal side - which has pitched a tent in us - sends things so that by perceiving, welcoming, becoming aware, we can prepare the development of the soul, of our Home.

Evolution whose principles [and opportunities to step forward towards the completion of our full and divine personality] we simply find innate, within, and not in extrinsic adhesions - typical of external civilisation and of not a few expressions of faith reduced to religion.

The Prologue of John only reiterates the eternal pillars of a Wisdom that is revealed but natural, within the reach of all because it narrates love, even in the inner journey; difficult to understand only for those who allow themselves to be influenced by opinions and coded, abbreviated catechisms.

The Gospel reassures: it is News in our favour, because it makes us aware that the "lords" who come along are Gifts that clean up the dwelling, and if they throw it away, it is only to strengthen our essence, chiselling an unrepeatable Vocation: the one capable of recovering every shred of our history and making it a masterpiece.

It would be impossible to take the road to full Happiness if we did not gather and assume every shred of our being scattered in the world and in time, making every expectation, every moment, every oscillation even broken, meaningful and divine.

The Logos has countless Seeds already planted in us: they are all mouldable energy polarities; not crystalline. Points of tension. Many of them seemingly unsteady, but restarting at the destination of completeness.

Provisionalities called to become fixed points - then wobbly again, because only through processes of fluctuation are the dynamics that will lead to total growth triggered - with other moments of Exodus.

As a Zen aphorism [collected in Ts'ai Ken T'an] suggests: "Water that is too pure has no fish".Jn does not write that the Logos became 'man', but 'flesh' in the Semitic sense of a being full of limits, unfinished; for this reason devoted to the incessant search for meaning, partial to the point of death.

The weakness of women and men is not redeemed by admiring a heroic model and imitating it off the scale, but in a process of recovery of the whole being and of our history.

There are no Gifts of the Spirit that do not pass through the human dimension.

Already here and now we thrive on the earth of a precious seed of the Word. His authentic Tent is in us and in all motives.

The more we can bring our creaturely and humanising reality to its fullest, the more we will be on the path to the divine condition. Rooted on the earth of the inestimable lineage generated by the Logos.

To make us conscious and dilate life, the Eternal asks that we host the proposals with which it bursts in, with the sole purpose not to condition us but to complete us, and increase the self-confidence with which we face the present and activate the future, face to face.

We will not do this by becoming winners, but by welcoming what comes from Providence, from people and emotions (even from discomforts) without prejudice - not even that of always seeming to be accompanied by many people, being seen on the outside as confident, strong, performing.

Scenarios that invade life and take away the essential Perception of being present to minimal acts and relationships, to looking in and out. Clear awareness of self, of the human, of the world that guides towards our direction and our true nature.

Not the Ten Words - a typical Semitic category - but the One inclusive Word, Dream and Meaning of Creation, are the foundation of the Father's Work.

The Logos that takes root is qualitative, not partial, nor centred on a single name: One because it is One.

The story of Jesus of Nazareth suggests that sin has been shattered, i.e.: imperfection is not an obstacle to communion with Heaven, but a spring.

Imperfections do not make us inadequate: they set us on our way.

The Lord has annihilated the sense of inadequacy of the carnal condition and the humiliation of unbridgeable distances.

The Creator's 'initial' project is to share his own Life with all humanity. In this way, the Lord enters the world with confidence, without fear of contamination, nor cuts and separations - prejudice typical of the archaic mentality.

The Plan of Salvation is realised and has its summit in the defence, promotion, expansion of our relational quality of life.

Therefore: "Light of men" (v.4) will no longer be - according to the convictions of the time - the arid regulations of the Law, but rather "Life" in its complete fullness. Spontaneous, real and unrefined: raw, therefore full of power.

The Tao Tê Ching (xix), which considers the most celebrated virtues to be external, writes: "Teach that there is something else to adhere to: show yourself simple and keep yourself raw".

Master Wang Pi comments: 'Formal qualities are totally insufficient'.

And Master Ho-shang Kung adds: "Forget the regularity and creation of the saints; return to what was at the Beginning".

Thus in the Paths of Faith, it is no longer outwardness or convention that dictates the path and wisdom in the discernment of spirits.

Each has its own innate desire for fulfilment and totality of expression: this will be the sole criterion of our path.

Such will remain the intimate Light that guides our steps; such the Word of the invisible Friend who leads us and acts as a canon.

"And the Light shines in the darkness" (v.5)!

Just like a plant, which neither takes root nor expands in a distilled environment.

So what does not have or limit life does not proceed from God, the Living One, the promoter of all that expresses and unfolds exuberance.

Our vocation is to stand alongside the integral life, with its opposite sides making a covenant.

Religions do not welcome all guests [they turn out to be far more fertile than we imagine] who knock on the inner hotel.

But it is not with the parameters of established thought that one can understand or discover what complete Life is, because Life is always expansive, lush and new, full of facets.

Hence the need for constant change, from the old.

In short, the single non-negotiable principle is the real good of the concrete man; the rest escapes our foresight.

The classic risk is that: in the name of a God of the past [doctrine, customs, disciplines, ways of thinking and doing] we fail to notice and recognise the invitation, the empathic energy; the divine virtue that protrudes Present.

In order to welcome the ever new and bubbling, we must allow access to all our soul 'guests' - who will allow us to meet ourselves; even the neuroses.

He who lives proposes a profound Exodus, to become ever-born again. Man's going is not subject to a Master, not even a heavenly one.

We do not exist 'for' God, as is believed and preached in ancient devotions. They clog us up with external or intimist forms; they block the development of personality.

They do not allow us to draw on "our" own strength.

The Father asks to be accepted, not obeyed. In this way we will live by Him, and with Him and like Him we will go out to meet our brothers and sisters, managing also to make ourselves Food for our neighbour - without restless constraints that depersonalise.

Here are at work the new Shrines of flesh and blood that have replaced, supplanted, that of stone.

Presences, meeting places between history, joy and vertigo; between human and divine nature. Centres of irradiation of Love without conditions - nor reductions.

No longer precisely named heights, inaccessible and distant places to go - on pain of exclusion - but images and likenesses of a God who comes to find us at home, where we are.

It is the same marginality encountered within - now without hysteria - that infallibly points us to the existential peripheries of others, which we are called to frequent, regenerate, sublimate, move, resurrect.

The new relationship with God is no longer founded on discrepant purity and obedience, lavished on rigid precepts and unquestioning conformity.

Rather, in personal vicissitudes and in the conviviality of differences, similarity to the Word will take over.

Patriarch Athenagoras confessed:

"We need Christ, without him we are nothing. But he needs us to act in history. The entire history of humanity from the resurrection onwards, and even from the origins onwards, constitutes a kind of pan-Christianity. The ancient covenant involves a whole series of covenants that still exist side by side today. And so the covenant of Adam, or rather of Noah, subsists in the archaic religions, those of India especially, with their cosmic symbolism [...].

We know that light radiates from a face. It took the covenant of Abraham, and it needed to be renewed in Islam. That of Moses subsists in Judaism [...].

But Christ recapitulated everything. The Logos who became flesh is he who creates the universe and manifests himself there, and he is also the Word who guides history through the prophets [...].

That is why I consider Christianity the religion of religions, and I happen to say that I belong to all religions'.

It is the Dream of each and all, in Christ already introduced into the bosom of the Eternal One who is convincing and lovable, because He is Comprehensive [not in the sense of paternalism eventually good-naturedly bestowed, but of Being].

As Pope Francis pointed out:

"In life bears fruit not he who has so many riches, but he who creates and keeps alive so many bonds, so many relationships, so many friendships through the different 'riches', that is, the different Gifts with which God has endowed him."

Only in this way will we - all of us in the Son - become special Events of the Word-flesh: small fish, but with full rights to the pre-eminence of the Logos... coryphaeans of impossible recoveries.

We have in common the displacement. Fine "Word" on univocity.

To internalise and live the message:

How do you start your days? Do you welcome your guests (even emptiness)? Or do you face them with excessive judgement?

Light and Treasure

Spark of beauty and humanism, or no future

(Jn 8:12-20)

In all religions the term Light is used as a metaphor for the forces of good.

On the lips of Jesus [present in his intimates] the same word stands for a fulfilment of humanity (even of the religious institution) according to the divine plan, recognisable in his own Person.

The distinction between light and darkness in Christ is somehow not comparable to the more conventional dualist binomial - about good and evil. The Creator's activity is multifaceted.

The evangelical term therefore does not designate any static fixed judgement on what is usually assessed as 'torch' or 'shadow', 'correct' or 'wrong' and so on.

There is room for new perceptions and reworkings. Nor are we always called upon to fight against everything else, and the passions.

Classical moral, pious or general religious evaluations must be overcome, because they remain on the surface and do not grasp the core of being and becoming humanising.

Not infrequently, the most valuable things arise precisely from what disturbs standardised thinking.

The same mind that believes it is only in the light is a one-sided, partial, sick mind; bound to an idea, therefore poor.

God knows that it is the incompletenesses that launch the Exodus, it can be the insecurities that keep us from crashing into the patterns... that make us lose who we are.

In fact, the energies that invest created reality have an entirely positive potential root.

Sunsets prepare other paths, ambivalences give the 'la' to impossible recoveries and growths.

"Light" was in Judaism the term that designated the righteous path of humanity according to the Law, without eccentricity or decline.But with Jesus, it is no longer the Torah that acts as a guide, but life itself [Jn 1:4: "Life was the Light of men"] that is characterised by its varying complexity.

Thus, even the "world" - that is, (in Jn) first and foremost the complex of the institution (so pious and devout) now installed and corrupted: it must return to a wiser Guide, one that illuminates real existence.

The appeal that Scripture addresses to us is very practical and concrete.

But in contexts with a strong structure of mediation between God and man, spirituality often tends towards the legalism of customary fulfilments.

Jesus is not for grand parades, nor for solutions that cloak people's lives in mysticism, escapism, rituals or abstinence.

All of this was perhaps also the fabric of much of medieval spirituality - and the assiduous, ritualistic, beghine spirituality of days gone by.

But in the Bible, God's servants do not have haloes. They are women and men normally inserted in society, people who know the problems of everyday life: work, family, bringing up children....

The professionals of the sacred, on the other hand, try to put a pretty dress on very ungodly things - sometimes cunning minds and perverse hearts. Cultivated behind the magnificent respectability of screens and incense.

To do this, Jesus understands that he must drive out both merchants and customers (Jn 2:13-25) and supplant the fatuous glow of the great sanctuary.

During the Feast of Tabernacles, huge street lamps were lit in the courtyards of the Temple in Jerusalem.

One of the main rituals consisted in staging an admirable night procession with lit fairies - and in making the great lamps shine (they rose above the walls and illuminated the whole of Jerusalem).

It was the appropriate context to proclaim the very Person of Christ as the authentic sacred and humanising Word, the place of encounter with God and the torch of life. There was nothing external and rhetorical about it.

But in that "holy world" marked by the intertwining of epic, religion, power and interest, the Master stands out - with contrary evidence - precisely in the place of the Treasury (the real centre of gravity of the Temple, v.20) as the true and only Extreme Point that pierces the darkness.

The Lord invites us to make our own his own sharply missionary path: from the shrine of stone to the heart of flesh, as free as that of the Father.

Clear call and intimate question that never goes out: we feel it burning alive without being consumed.

There is no need to fear: the Envoy is not alone. He does not testify to himself, nor to his own foibles or utopian derangements: his Calling by Name becomes divine Presence - Origin, Path, authentic "Return".

Do we look like pilgrims and exiles who do not know how to be in "the world"? But each of us is (in Faith) like Him-and-the-Father: overwhelming majority.

By Faith, in the authentic Light: Dawn, Support, Friendship and unequivocal, invincible leap, which rips through the haze.

It bursts from the core, assuming the same shadows and being reborn; bringing our dark sides alongside the roots.

Intimate place and time (outside of all ages) from which the outgoing Church springs forth: here it is from the jewels and sacristies, to the peripheries Spark of beauty and humanism, or without a future

And from the sacred society of the outside, to the hidden Pearl that genuinely connects the present with the 'timelessness' of the Free - even if here and there it undermines so much theology with its preceptistic, greedy and cunning meaning, neither plural nor transparent.

In the end, it is all simple: the full wellbeing and integrity of man is more important than the one-sided 'good' of doctrine and institution - which advocates it without even believing in it.

To internalise and live the message:

In what situations do I consider myself a "Witness"?

What is the torch in my steps? Who is my Present Light?

Mysticism of Coversion-Light: the unseen spaces of growth

Waiting and Receiving (the taste of God, in Rebirth)

(Jn 12:44-50)

"He that despiseth me, and receiveth not my words, hath he that judgeth him: the Word that I have spoken, that shall judge him in the last day" (v.48).

"And I know that his Commandment is the Life of the LORD. The things therefore that I proclaim, as the Father has spoken to me, so I proclaim" (v.50).

We are at the end of the Book of Signs (Jn 2-12) which is followed by the so-called time of the Hour.

The particular Gospel passage of Jn 12 acts as an inclusion to the Prologue, and introduces the final drama of Christ - with all the weight of unbelief already perceived.

But it is a primordial imprint, also for us, generated to life by the animation in the Spirit of the Son, to be sent to the Annunciation (of likeness, not obedience).

Like Him we are in God, and together... for the women and men of every time and culture.

Therefore, Jesus' "cry" (v.44) is a privileged "clamour", of decisive self-presentation, as well as of unprecedented revelation of the very Life of the Eternal already present here (v.50) within ourselves.He who acts in the name of Risen Love, brings forth the glad tidings of resurrection and deliverance, and the definitive approval of the Father.

We are no longer in the world as a function of God (as in religions) but live with Him and of Him - for the Message and Mission: the complete humanisation, emancipation, redemption of mankind.

Father and Son are One. Jesus reflects God, brings Him closer to us; He reveals and communicates Him to us, without a gap.

So for us "Seeing" Christ means believing him, that is, grasping the glorious outcome of a life that seemed destined for insignificance.

The indispensable Light of the Lord not only dispels the darkness, but uncovers, encounters and transforms it from within. And unbelief becomes Faith - like a Womb of gestations, gifts of new Creation.

Our fate and quality of believing life is tightly decided in the confrontation between two motions: pious life, or Vision-Faith. The latter able to unleash dilations and ministerial imperatives.

This dilemma acts as a dividing line: between a life as saved now, and doubt about future destiny. A question typical of empty spirituality - or of romantic visions that after the first enthusiasms lead to groping in the dark, in dissatisfaction.

Original adherence to Christ is in the state of the Task, germinated in the bosom - not planned at the table nor prepared on the sidelines without the faces, the ways, and with only national or local history - or mannerisms.

In Christ we do not eagerly cling to ourselves, to the conforming environment, to ancient knowledge or to the most reassuring fashion. We are prepared for an itinerary of continuous beginnings, as if on the trail of guide-images (changing, but knowing where to go).

We will encounter the Action of God that saves... precisely in the unexpected territories that transcend the sanctuary of habits. And in the ways that gloss over our old intentions - though in themselves confessional, plausible, or even noble.

The Law chock-full of chiselled verdicts is outdated (v.47). Christ did not come to accuse us of inadequacy and punish us: on the contrary, to make us invent ways - and unheard-of torches.

Criterion of 'judgement' is the Word and his Person, transparency of the Father - absolute, genuine and free coincidence. He as the Eternal One comes for surpassing Life; and new Light.

Not to regard him as a seal of exception, a step and rhythm to be reinterpreted, and not to give him space as an intrinsic trait, motive and motor, is to dissipate in vain the best energies - which make us wander, yes, but to lead to fullness.

The world is not all there is: there is a clarity (v.46) that makes one feel at home and can dispel all disturbance, closure and darkness.

This is the great 'conversion', the mindset to be renewed, enjoying the Call to the full.

Life in Christ is not - as in various archaic religious forms - restricted against oneself and the world.

It is to assert the Action of the Father (vv.43-44.49-50) who has disposed that even eccentricities, hardships, discomforts may convey to us the idea, the taste, of a different fulfilment; open spaces of unexpressed growth.

The Inner Friend mysteriously leads to the crumbling of the proud self that rushes to adjust according to conventional and other people's opinions - so that we allow ourselves to radiate.

It is this eminent and intense Self of uniqueness that will make us grasp the astonishing (impossible) fruitfulness of victory in defeat, of triumph through loss, of life amidst signs of death.

By thinning out the Call of Darkness, we risk pushing away the new Light, a further genesis of ourselves, an evolution different from the usual expectations - which would really comfort and fulfil us.

By removing the perception of wounds we risk annihilating the healing and rebirth process of the soul.

This is the new decisive Conversion: the true emptying out of one's own plans, ideas and tastes, in order to be inspired by the unthinkable divine Work within us - which does not want to weaken the self but strengthen it with other capacities.

The fullness of extraordinary Light is in Christ a simple (but inverted) self-denial: granting space and time to that Totality that does not take over the Person.

As in Jesus, then it will allow for authenticity and much more than minimal wavering lights, products of a small brain (which does not evolve).

Struggling with symptoms would end up chronicising them - with the drug of ancient or immediately at hand remedies.

It would make us become external and extinguish the inner Genesis, which tinkles with the Coming Work.

In Christ we know the secret of welcoming conversion: the kingdom we do not see can take care of us and the world (vv.47-48).

It is this reference to the Mystery (which calls) that congenital Seed that realises the evolution of the cosmos and of each one, because it possesses the Sense of springing authenticity - and it will bear its Fruit.In the Faith "spark, / which expands into flame then lively / and like a star in heaven in me sparkles" (Dante, Paradise c.XXIV).

To internalise and live the message:

What light did you anticipate cured you and vice versa chronicled your situation? What external crutch has addicted you and made you lame?

Spiritual meaning of Christmas

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

On this very day, the days of Advent that directly prepare us for the Nativity of the Lord begin: we are in the Christmas Novena which in many Christian communities is celebrated with liturgies rich in biblical texts, all oriented to fostering the expectation of the Saviour's Birth. Indeed, the whole Church focuses her gaze of faith on this Feast that is now at hand, preparing herself, as she does every year, to join in the joyful singing of the Angels who will announce to the shepherds in the heart of the night the extraordinary event of the Birth of the Redeemer, inviting them to go to the Grotto in Bethlehem. It is there that the Emmanuel lies, the Creator who made himself a creature, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a poor manger (cf. Lk 2: 13-16).

Because of the atmosphere that distinguishes it, Christmas is a universal celebration. In fact, even those who do not profess themselves to be believers can perceive in this annual Christian event something extraordinary and transcendent, something intimate that speaks to the heart. It is a Feast that praises the gift of life. The birth of a child must always be an event that brings joy; the embrace of a newborn baby usually inspires feelings of kindness and care, of emotion and tenderness. Christmas is the encounter with a newborn baby lying in a humble grotto. In contemplating him in the manger, how can we fail to think of all those children who continue to be born today in great poverty in many regions of the world? How can we fail to think of those newborn infants who are not welcomed, who are rejected, who do not manage to survive because of the lack of care and attention? How can we fail to think also of the families who long for the joy of a child and do not see their hope fulfilled? Unfortunately, under the influence of hedonist consumerism Christmas risks losing its spiritual meaning and being reduced to a mere commercial opportunity for purchases and the exchange of gifts! However, it is true that the difficulties, the uncertainties and the financial crisis itself that numerous families have had to come to terms with in recent months and which is affecting all humanity could be an incentive to rediscover the warmth of simplicity, friendship and solidarity: typical values of Christmas. Stripped of its consumerist and materialistic encrustations, Christmas can thus become an opportunity for welcoming, as a personal gift, the message of hope that emanates from the mystery of Christ's Birth.

However, none of this enables us to fully grasp the ineffable value of the Feast for which we are preparing. We know that it celebrates the central event of history: the Incarnation of the divine Word for the redemption of humanity. In one of his many Christmas Homilies, St Leo the Great exclaims: "Let us be glad in the Lord, dearly-beloved, and rejoice with spiritual joy that there has dawned for us the day of ever-new redemption, of ancient preparation, of eternal bliss. For as the year rolls round, there recurs for us the commemoration of our salvation, which promised from the beginning, accomplished in the fullness of time will endure for ever" (Homily XXII). St Paul returns several times in his Letters to this fundamental truth. For example, he writes to the Galatians: "When the time had fully come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law... so that we might receive adoption as sons" (4: 4). In the Letter to the Romans he highlights the logic and the demanding consequences of this salvific event: "If we are children of God... then [we are] heirs, heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him" (8: 17). However, in the Prologue to the fourth Gospel, it is above all St John who meditates profoundly on the mystery of the Incarnation. And it is for this reason that the Prologue has been part of the Christmas liturgy since the very earliest times. Indeed, in it are found the most authentic expression and the most profound synthesis of this Feast and of the basis of its joy. St John writes: "Et Verbum caro factum est et habitavit in nobis / and the Word became flesh and dwelt among us" (Jn 1: 14).

At Christmas, therefore, we do not limit ourselves to commemorating the birth of a great figure: we do not simply and abstractly celebrate the birth of the man or in general the mystery of life; even less do we celebrate only the beginning of the new season. At Christmas we commemorate something very tangible and important for mankind, something essential for the Christian faith, a truth that St John sums up in these few words: "The Word became flesh". This was a historical event that the Evangelist Luke was concerned to situate in a well-defined context: in the days when the decree was issued for the first census of Caesar Augustus, when Quirinius was Governor of Syria (cf. Lk 2: 1-7). Therefore, it was on a historically dated night that the event of salvation occurred for which Israel had been waiting for centuries. In the darkness of the night of Bethlehem a great light really was lit: the Creator of the universe became flesh, uniting himself indissolubly with human nature so as truly to be "God from God, Light from Light" yet at the same time a man, true man. What John calls in Greek "ho logos" translated into Latin as "Verbum" and Italian as "il Verbo" also means "the Meaning". Thus we can understand John's words as: the "eternal Meaning" of the world made himself tangible to our senses and our minds: we may now touch him and contemplate him (cf. 1 Jn 1: 1). The "Meaning" that became flesh is not merely a general idea inherent in the world; it is a "Word" addressed to us. The Logos knows us, calls us, guides us. The Word is not a universal law within which we play some role, but rather a Person who is concerned with every individual person: he is the Son of the living God who became man in Bethlehem.

To many people, and in a certain way to all of us, this seems too beautiful to be true. In fact, here it is reaffirmed to us: yes, a meaning exists, and the meaning is not a powerless protest against the absurd. The meaning has power: it is God. A good God who must not be confused with any sublime and remote being, whom it would never be possible to reach, but a God who made himself our neighbour and who is very close to us, who has time for each one of us and who came to stay with us. It then comes naturally to ask ourselves: "However could such a thing be possible? Is it dignified for God to make himself a child?". If we are to seek to open our hearts to this truth that illuminates the whole of human existence we must bend our minds and recognize the limitations of our intelligence. In the Grotto of Bethlehem God shows himself to us as a humble "infant" to defeat our arrogance. Perhaps we would have submitted more easily to power and wisdom, but he does not want us to submit; rather, he appeals to our hearts and to our free decision to accept his love. He made himself tiny to set us free from that human claim to grandeur that results from pride. He became flesh freely in order to set us truly free, free to love him.

Dear brothers and sisters, Christmas is a privileged opportunity to meditate on the meaning and value of our existence. The approach of this Solemnity helps us on the one hand to reflect on the drama of history in which people, injured by sin, are perennially in search of happiness and of a fulfilling sense of life and death; and on the other, it urges us to meditate on the merciful kindness of God who came to man to communicate to him directly the Truth that saves, and to enable him to partake in his friendship and his life. Therefore let us prepare ourselves for Christmas with humility and simplicity, making ourselves ready to receive as a gift the light, joy and peace that shine from this mystery. Let us welcome the Nativity of Christ as an event that can renew our lives today. The encounter with the Child Jesus makes us people who do not think only of themselves but open themselves to the expectations and needs of their brothers and sisters. In this way we too will become witnesses of the radiance of Christmas that shines on the humanity of the third millennium. Let us ask Mary Most Holy, Tabernacle of the Incarnate Word, and St Joseph, the silent witness of the events of salvation, to communicate to us what they felt while they were waiting for the Birth of Jesus, so that we may prepare ourselves to celebrate with holiness the approaching Christmas, in the joy of faith and inspired by the commitment to sincere conversion.

Happy Christmas to you all!

[Pope Benedict, General Audience 17 December 2008]

5. The fullest synthesis of this truth is contained in the Prologue of the Fourth Gospel. It can be said that in that text the truth about the divine pre-existence of the Son of Man acquires a further, in a certain sense definitive explication: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God: all things were made through him . . . In him was life, and the life was the light of men; the light shines in the darkness, but the darkness did not receive it" (Jn 1:1-5).

In these phrases the evangelist confirms what Jesus said of himself when he declared: "I came forth from the Father and have come into the world" (Jn 16:28), or when he prayed that the Father would glorify him with that glory that he had taken of him before the world was (cf. Jn 17:5). At the same time, the pre-existence of the Son in the Father is closely connected with the revelation of the Trinitarian mystery of God: the Son is the eternal Word, he is "God from God", of the same substance as the Father (as the Council of Nicaea expressed it in the Symbol of Faith). The Council formula precisely reflects John's Prologue: "The Word was with God and the Word was God". Affirming the pre-existence of Christ in the Father is tantamount to recognising his Divinity. To his substance, as to the substance of the Father, belongs eternity. This is what is indicated by the reference to the eternal pre-existence in the Father.

6. John's Prologue, through the revelation of the truth about the Word contained therein, constitutes as it were the definitive completion of what the Old Testament had already said about Wisdom. See, for example, the following statements: "Before the ages, from the beginning he created me; for all eternity I shall not fail" (Sir 24:9), "My creator pitched my tent and said to me: pitch your tent in Jacob" (Sir 24:8). Wisdom, of whom the Old Testament speaks, is a creature and at the same time has attributes that place her above the whole of creation: "Though unique, she can do all things; though remaining in herself, she renews all things" (Wis 7:27).

The truth about the Word, contained in John's Prologue, reconfirms in a certain sense the revelation about wisdom in the Old Testament, and at the same time transcends it in a definitive way. The Word not only "is with God", but "is God". Coming into this world in the person of Jesus Christ, the Word "came among his own people", for "the world was made through him" (cf. Jn 1:10-11). He came among "his own" because he is "the true light, the one who enlightens every man" (cf. Jn 1:9). The self-revelation of God in Jesus Christ consists in this "coming" into the world of the Word, who is the eternal Son.

7. "The Word became flesh and dwelt among us; and we beheld his glory, glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth" (Jn 1:14). Let us say it once again: John's Prologue is the eternal echo of the words with which Jesus says: "I came forth from the Father and have come into the world" (Jn 16:28), and of those with which he prays that the Father will glorify him with that glory that he had with him before the world was (cf. Jn 17:5). The Evangelist has before his eyes the Old Testament revelation about Wisdom, and at the same time the entire Paschal event: the departure through the cross and the resurrection, in which the truth about Christ, Son of Man and true God, became completely clear to those who were his eyewitnesses.

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 2 September 1987]

The Word of God does not offer us an episode from the life of Jesus, but rather it tells us about him before he was born. It takes us back to reveal something about Jesus before he came among us. It does so especially in the prologue of the Gospel of John, which begins: “In the beginning was the Word” (Jn 1:1). In the beginning: are the first words of the Bible, the same words with which the creation account begins: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen 1:1). Today, the Gospel says that Jesus, the One we contemplated in his Nativity, as an infant, existed before: before things began, before the universe, before everything. He existed before space and time. “In him was life” (Jn 1:4), before life appeared.

Saint John calls Him the Verbum, that is, the Word. What does he mean by this? The word is used to communicate: one does not speak alone, one speaks to someone. One always speaks to someone. When we are in the street and we see people who talk to themselves, we say, “This person, something has happened to him...”. No, we always speak to someone. Now, the fact that Jesus was the Word from the very beginning means that from the beginning God wants to communicate with us. He wants to talk to us. The only-begotten Son of the Father (cf. v.14) wants to tell us about the beauty of being children of God; He is “the true light” (v. 9) and wants to keep us distant from the darkness of evil; He is “the life” (v. 4), who knows our lives and wants to tell us that he has always loved them. He loves us all. Here is today’s wondrous message: Jesus is the Word, the eternal Word of God, who has always thought of us and wanted to communicate with us.

And to do so, he went beyond words. In fact, at the heart of today’s Gospel we are told that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (v. 14). The Word became flesh : why does Saint John use this expression “flesh”? Could he not have said, in a more elegant way, that the Word was made man ? No, he uses the word flesh because it indicates our human condition in all its weakness, in all its frailty. He tells us that God became fragile so he could touch our fragility up close. Thus, from the moment the Lord became flesh, nothing about our life is extraneous to him. There is nothing that he scorns, we can share everything with him, everything. Dear brother, dear sister, God became flesh to tell us, to tell you that he loves you right there, that he loves us right there, in our frailties, in your frailties; right there, where we are most ashamed, where you are most ashamed. This is bold, God’s decision is bold: He became flesh precisely where very often we are ashamed; He enters into our shame, to become our brother, to share the path of life.

He became flesh and never turned back. He did not put on our humanity like a garment that can be put on and taken off. No, he never detached himself from our flesh. And he will never be separated from it: now and forever he is in heaven with his body made of human flesh. He has united himself forever to our humanity; we might say that he “espoused” himself to it. I like to think that when the Lord prays to the Father for us, he does not merely speak: he shows him the wounds of the flesh, he shows him the wounds he suffered for us. This is Jesus: with his flesh he is the intercessor, he wanted to bear even the signs of suffering. Jesus, with his flesh, is before the Father. Indeed, the Gospel says that He came to dwell among us . He did not come to visit us, and then leave; He came to dwell with us, to stay with us. What, then, does he desire from us? He desires a great intimacy. He wants us to share with him our joys and sufferings, desires and fears, hopes and sorrows, people and situations. Let us do this, with confidence: let us open our hearts to him, let us tell him everything. Let us pause in silence before the Nativity scene to savour the tenderness of God who became near, who became flesh. And without fear, let us invite him among us, into our homes, into our families. And also — everyone knows this well — let us invite him into our frailties. Let us invite him, so that he may see our wounds. He will come and life will change.

May the Holy Mother of God, in whom the Word became flesh, help us to welcome Jesus, who knocks on the door of our hearts to dwell with us.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 3 January 2021]

Without stopping in the middle, and without fashion. New Light

Church of the little ones: Challenge and recognised course

Lk 2:36-40 (22-40)

The Gospel passage from Lk recounts the Father's surprising response to the predictions of fulfilment regarding the messianic prophecies.

An eloquent and peremptory manifestation of the power of the God of Israel, and the submission of those who did not fulfil the Law was expected.

Everyone imagined witnessing the triumphal entry of a leader - surrounded by military leaders or angelic hosts (Mal 3:1) - who would subjugate the pagans by bringing their possessions into the holy city, grant the chosen people many slaves, and impose observance.

Jesus? There He is in the Temple, but helpless and accompanied by insignificant people.

Nobody notices Him, although at all hours the holy place was swarming with visitors.

Then arise here Simeon and Hanna (vv.25.36-38), men and women coryphaeans of the most sensitive authentic People.

They grasp a Clarity that produces conflict with habitual officialdom, a profound Splendour destined for all time.

And the «sword» (v.35) that in Mother Israel will bring about lacerations: between some who open up to the new Light, and others who conversely entrench.

Lk is evaluating community situations, where believers in Christ are discarded by friends and families from different cultural backgrounds (cf. Lk 12:51-53).

But the awaited and true Messiah must be delivered to the world - although those best prepared to recognize him are the members of tribe of Israel the smallest [Asher, in the figure of Hanna: vv.36-38].

These are the same prophets who vibrated in life for one great Love (vv.36-37), then experienced the absence of the Beloved - until they recognised him in Christ. By startling in surprise - catching very personal correspondences within themselves, in Spirit; rejoicing, praising the Gift of God (v.38).

The passage concludes with the return to Nazareth (vv.39-40) and the note concerning Jesus' own growth «in wisdom, stature and grace».

We, too, are not in the world to cling to shadows and blockages, the same old moods, the same prevailing thoughts, the same way of doing (even the little things).

Mechanisms and comparisons that close our days, our whole lives and the emotional space of passions - clipping the wings of testimonies that want to override the 'recognised course'.

Let us sweep away the layers of dust that still cover us with conformism and proven manners, which follow expectations of others, of contours, of external intrusive conditions!

This is precisely the great Challenge that activates the young rebirth of the Dream of God.

It can launch the soul in the transition from the common religious sense to a new Torch: personal, pro-active, liberating Faith.

Relationship of love that does not extinguish us.

[December 30, sixth day between the Octave of Christmas]

Without stopping in the middle, and without fashion. New Torch

Church of the little ones

Lk 2:36-40 (22-40)

The Gospel passage from Lk narrates the Father's surprising response to the predicted fulfilment of the messianic prophecies.

An eloquent and peremptory manifestation of the power of the God of Israel and the submission of those who did not fulfil the Law was expected.

Everyone imagined that they would witness the triumphal entry of a leader - surrounded by military leaders or angelic hosts (Mal 3:1) - who would subjugate the pagans by bringing their possessions into the holy city, grant the chosen people many slaves, and enforce observance.

Jesus? Here he is in the Temple, but defenceless and accompanied by insignificant people. No one notices them, although at all hours the holy place is swarming with visitors.

It is not enough to be pious and devout people to realise the presence of Christ - to see God himself, one's brothers and sisters, and things with the eyes of the Father.

How can one break through the wall of self-enclosed customs, how can one break through the artificial world of contrary appearances, to turn to the creative Unknown?

Lk answers: with the help of particularly sensitive people, capable of understanding the New Project.

They are those who do not oppose the Design of the Most High with banal intentions, or current dreams; the habitual expectations (of others)... demanding from the Lord only the help to realise them.

Here then arise Simeon and Anna (vv.25.36-38), men and women coryphaeans of the most sensitive authentic People, thanks to excellent work on the soul.

Coming both from inside and outside the Temple - such prophets attempt to block (vv.28.38 Greek text) the small family procession, still bound by Judaic conventions (vv.21-23).

Compared to cultic and legalistic stereotypes, the members of the holy family must take a different, conscious Path.

A path that will lead it to unforeseen growth, for the benefit of all.

Thus, the Tiny Holy Remnant of Spirit-animated women and men burst in (always) as if they were strangers...

People of tiny worshippers, of genuine outsiders, who even try to prevent the 'same' useless clan ritual!

A gesture that pretended - again - to transform (and reduce) into an obsequious son of Abraham the One who had been announced as the Son of God.

In short, in the figures of Simeon and Anna, Lk wants to convey to us a fundamental teaching.

If the goal is the triumph of life, past history must not take precedence over unheard-of revelation.

Divine Oneness is manifested in what happens.

The Exceptionality of the Spirit proposes itself (dimly) now.

Unexpectedness to which we are called to give full voice - and echo.

The unveiling is now.

The 'here' immediately opens an arc of full existence.

(No more repeating 'how we should be' according to customs or fathers...).

Where everything is combined, we will not find the answers that solve real problems, nor magic times - those that motivate us.

Genuine God souls are not in the business of pandering to obligations, but of living intensely in the present moment with the energy that charts the future, without hesitating with the excesses of control.

Stepping out of the normality of the established way - even through labour pains (vv.34-35) - creates space to welcome the Newness that saves.

Along the way, those thoughts and duties that no longer correspond to one's destiny will be defused, will evaporate by themselves.

Thus in Mary: Mother icon of the whole Church of true expectations - cut off (v.35) from the habitual crowd.

She has laid down all dependencies.

And the Innocent One is the glory of the 'nation', in Spirit - because she comes out of it!

In her unpredictable and healthy figure resides a Light that enlightens all (v.32).

A trait of childhood and simple immediacy that becomes the "redemption of Jerusalem" (v.38).

It is in fact a Light that produces conflict with officialdom, a profound Splendour destined for all time - while the astute do not want to know about losing coordinates, roles and positions.

A "sword" (v.35) that in Mother Israel will bring about lacerations between some who open themselves to the torch of the Gospel and others who, on the other hand, retreat.

Lk has in mind community situations, where believers in Christ are discarded by friends and families from different cultural backgrounds (cf. Lk 12:51-53).

But the awaited and true Messiah must be delivered to the world - although those best prepared to recognise him are the members of the smallest tribe of Israel (Asher, in the figure of Anna: vv.36-38).

These are the same prophets who in life vibrated for one great Love (vv.36-37), then experienced the absence of the Beloved - until they recognised him in Christ. Rejoicing in surprise - catching personal correspondences within themselves, in the Spirit; rejoicing, praising the Gift of God (v.38).

The passage concludes with the return to Nazareth (vv.39-40) and the note concerning Jesus' own growth "in wisdom, stature and grace" (Greek text).Moral: we are not in this world to cling to shadows and blocks of the past, with its perennial feelings - same old moods, same prevailing thoughts, same way of doing things (even the little things).

Mechanisms and comparisons that close off our days, our whole life and the emotional space of passions - clipping the wings of testimonies that want to override the course recognised since our ancestors.

Conversely, this is precisely the great Challenge that activates the young Rebirth of the Dream of God. And launches us into the transition from religious sense to personal Faith.

Such is the only energy that awakens, awakens enthusiasm, communicates simple virtue, sweeps away the layers of dust that still cover us with conformity.

The recalcitrant and collective ways of coming into the field (more or less 'moral') point at, deviate from, overload our essence - appealing to the fear of being rejected.

To slip effortlessly into the conventions and manners of our local culture, we often risk losing the Calling by Name, the unrepeatability of the path that vibrates within and truly belongs to us.

Compared to the religious guerrilla warfare waged even with oneself, a respite from common forms - even devout, cultic and purist ones - is needed.

A break from the social self-image, to allow us to abandon external and toxic forms, recover silent energies.

And to launch ourselves into the new experiences we want and are called upon to embrace, with enthusiasm, without first stepping into a role.

Lost and found: Salvation in a young and open "place

Already rebellious: Particular vocation

(Lk 2:41-51)

The family is the nucleus of society and the privileged place of educational risk, not the only one.

It is a precious stage of growth, but it must not hinder the flowering in the universal dimension.

The movement of Salvation familiarises everyone with the dynamics of loss [from the narrowness] and rediscovery [of a Presence within the dissimilar presences] in order not to narrow horizons.

The complacent retreat into the world of kinship affections and interests reduces the dimension of vital frontiers, making personal and household life narrow; cultural, social and spiritual.

The domestic hearth must integrate them into the community, and introduce young people to the innate character of their vocation, so that as they grow up they become available and mature in an ever wider reality.

The family that becomes a stepping stone preludes detachment, which in its cut will be painful for all - but it will become a taking flight from the protected nest that enslaves; a leap towards the freedom of full life.

The Gospel passage baffles because it seems to portray a distracted family and an already grumpy and rebellious Jesus.

Lk writes more than half a century after the Lord's death and resurrection.

The tragic story of the Master is understood and internalised in a way that perhaps Joseph and Mary could not yet have guessed in their adolescence.

Recognising Jesus as the Son of God from the age of twelve meant in the literature of the time "covering" his entire life [cf. Lk 24].

It seems that the Holy Family went up to Jerusalem every year for the Passover (v.41).

Before one became an adult in Israel and bound to the observance of the Torah (13 years old), our Adolescent already shows signs of a special vocation.

From the tone of the narration one can see a Jesus eager to drink in and immerse himself in the as yet unexpressed Mystery of the Father.

Dreaming of discovering his Will, he stays in the holy city to fully understand the Word of God - without settling for impersonal, abbreviated catechisms.

The first expressions of Jesus in the third Gospel mark the character of his whole story. He decisively distances himself from the religiosity of the fathers (v.49).

He begins to distance himself from the ideas common even to his family of origin: he does not belong to a defined clan.

His will be a divine proposal on behalf of all the women and men of the world.

In this sense, Jesus even more honoured his parents' loyalty to God (vv.51-52) by accepting the whole spirit of their teachings, and digging deeper - intuiting their ultimate meaning.

As if to say: in him, the sacred Scriptures become accessible, with the key to understanding his entire life and Person.

Life for us (even before Baptism and the public event).

Lk writes to encourage believers who did not yet understand everything about the new Rabbi's story.

Like Joseph and Mary, they had to realise that it is not easy to understand the Son of God and accept his uniqueness of character, even to the point of earthly defeat.

In the figure of the holy family, we too are invited to "return to Jerusalem" (v.45).

Here, observing the autonomy of Christ, we will gradually be able to open ourselves to the unprecedented vocation we carry within - because we are "born again" in Him.And in the face of disconcerting events, we will learn to cherish the personal calling - like Mary.

For she too did not find it easy to enter her Easter: the "passage" from the religion of traditions and expectations to Faith in her Son.

But she "kept through" Word and events (v.51b), without stopping in the middle.

The reflective aspect of the House of Nazareth

The house of Nazareth is the school where one is initiated to understand the life of Jesus, that is, the school of the Gospel. Here we learn to observe, to listen, to meditate, to penetrate the meaning so profound and so mysterious of this manifestation of the Son of God so simple, so humble and so beautiful. Perhaps we also learn, almost without realising it, to imitate.

Here we learn the method that will enable us to know who Christ is. Here we discover the need to observe the framework of his sojourn among us: that is, the places, the times, the customs, the language, the sacred rites, everything, in short, that Jesus used to manifest himself to the world.

Here everything has a voice, everything has a meaning. Here, at this school, we certainly understand why we must keep a spiritual discipline, if we want to follow the doctrine of the Gospel and become disciples of Christ. Oh! how willingly we would like to become children again and put ourselves to this humble and sublime school of Nazareth! How ardently we would wish to begin again, close to Mary, to learn the true science of life and the superior wisdom of divine truths! But we are but passing through, and it is necessary for us to lay aside the desire to continue to learn, in this house, the unfinished training in the understanding of the Gospel. However, we will not leave this place without having picked up, almost furtively, some brief admonitions from the house of Nazareth.

Firstly, it teaches us silence. Oh! would that there were reborn in us an appreciation of silence, an admirable and indispensable atmosphere of the spirit: while we are stunned by so many noises, rumblings and clamorous voices in the exaggerated and tumultuous life of our time. O Silence of Nazareth, teach us to be firm in good thoughts, intent on the inner life, ready to hear God's secret inspirations and the exhortations of the true teachers. Teach us how important and necessary are the work of preparation, study, meditation, the interiority of life, prayer, which God alone sees in secret.

Here we understand the way of life in the family. Nazareth reminds us what the family is, what the communion of love is, its austere and simple beauty, its sacred and inviolable character; let us see how sweet and irreplaceable education in the family is, teach us its natural function in the social order. Finally, let us learn the lesson of work. Oh! dwelling place of Nazareth, home of the carpenter's Son! Here above all we wish to understand and celebrate the law, severe of course but redeeming of human toil; here to ennoble the dignity of work so that it is felt by all; to remember under this roof that work cannot be an end in itself, but that it receives its freedom and excellence, not only from what is called economic value, but also from what turns it to its noble end; here finally we wish to greet the workers of the whole world and show them the great model, their divine brother, the prophet of all the just causes that concern them, that is Christ our Lord.

[Pope Paul VI, Church of the Annunciation Nazareth 5 January 1964].

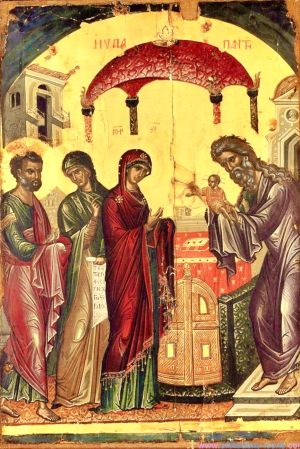

Light for a journey that interprets the profound meaning of events

[Today's Feast of Jesus' Presentation at the temple 40 days after his birth] places before our eyes a special moment in the life of the Holy Family: Mary and Joseph, in accordance with Mosaic law, took the tiny Jesus to the temple of Jerusalem to offer him to the Lord (cf. Lk 2: 22). Simeon and Anna, inspired by God, recognized that Child as the long-awaited Messiah and prophesied about him. We are in the presence of a mystery, both simple and solemn, in which Holy Church celebrates Christ, the Anointed One of the Father, the firstborn of the new humanity.

The evocative candlelight procession at the beginning of our celebration has made us relive the majestic entrance, as we sang in the Responsorial Psalm, of the One who is "the King of glory", "the Lord, mighty in battle" (Ps 24[23]: 7, 8). But who is the powerful God who enters the temple? It is a Child; it is the Infant Jesus in the arms of his Mother, the Virgin Mary. The Holy Family was complying with what the Law prescribed: the purification of the mother, the offering of the firstborn child to God and his redemption through a sacrifice.

In the First Reading the Liturgy speaks of the oracle of the Prophet Malachi: "The Lord... will suddenly come to his temple" (Mal 3: 1). These words communicated the full intensity of the desire that had given life to the expectation of the Jewish People down the centuries. "The angel of the Covenant" at last entered his house and submitted to the Law: he came to Jerusalem to enter God's house in an attitude of obedience.

The meaning of this act acquires a broader perspective in the passage from the Letter to the Hebrews, proclaimed as the Second Reading today. Christ, the mediator who unites God and man, abolishing distances, eliminating every division and tearing down every wall of separation, is presented to us here.

Christ comes as a new "merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God, to make expiation for the sins of the people" (Heb 2: 17). Thus, we note that mediation with God no longer takes place in the holiness-separation of the ancient priesthood, but in liberating solidarity with human beings.

While yet a Child, he sets out on the path of obedience that he was to follow to the very end.

The Letter to the Hebrews highlights this clearly when it says: "In the days of his earthly life Jesus offered up prayers and supplications... to him who was able to save him from death.... Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered; and being made perfect he became the source of eternal salvation to all who obey him" (cf. Heb 5: 7-9).

The first person to be associated with Christ on the path of obedience, proven faith and shared suffering was his Mother, Mary. The Gospel text portrays her in the act of offering her Son: an unconditional offering that involves her in the first person.

Mary is the Mother of the One who is "the glory of [his] people Israel" and a "light for revelation to the Gentiles", but also "a sign that is spoken against" (cf. Lk 2: 32, 34). And in her immaculate soul, she herself was to be pierced by the sword of sorrow, thus showing that her role in the history of salvation did not end in the mystery of the Incarnation but was completed in loving and sorrowful participation in the death and Resurrection of her Son.

Bringing her Son to Jerusalem, the Virgin Mother offered him to God as a true Lamb who takes away the sins of the world. She held him out to Simeon and Anna as the proclamation of redemption; she presented him to all as a light for a safe journey on the path of truth and love.

The words that came to the lips of the elderly Simeon: "My eyes have seen your salvation" (Lk 2: 30), are echoed in the heart of the prophetess Anna. These good and devout people, enveloped in Christ's light, were able to see in the Child Jesus "the consolation of Israel" (Lk 2: 25). So it was that their expectation was transformed into a light that illuminates history.

Simeon was the bearer of an ancient hope and the Spirit of the Lord spoke to his heart: for this reason he could contemplate the One whom numerous prophets and kings had desired to see: Christ, light of revelation for the Gentiles.

He recognized that Child as the Saviour, but he foresaw in the Spirit that the destinies of humanity would be played out around him and that he would have to suffer deeply from those who rejected him; he proclaimed the identity and mission of the Messiah with words that form one of the hymns of the newborn Church, radiant with the full communitarian and eschatological exultation of the fulfilment of the expectation of salvation. The enthusiasm was so great that to live and to die were one and the same, and the "light" and "glory" became a universal revelation.

Anna is a "prophetess", a wise and pious woman who interpreted the deep meaning of historical events and of God's message concealed within them. Consequently, she could "give thanks to God" and "[speak of the Child] to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem" (Lk 2: 38).

Her long widowhood devoted to worship in the temple, fidelity to weekly fasting and participation in the expectation of those who yearned for the redemption of Israel culminated in her meeting with the Child Jesus.

Dear brothers and sisters, on this Feast of the Presentation of the Lord the Church is celebrating the Day of Consecrated Life. This is an appropriate occasion to praise the Lord and thank him for the precious gift represented by the consecrated life in its different forms; at the same time it is an incentive to encourage in all the People of God knowledge and esteem for those who are totally consecrated to God.

Indeed, just as Jesus' life in his obedience and dedication to the Father is a living parable of the "God-with-us", so the concrete dedication of consecrated persons to God and to their brethren becomes an eloquent sign for today's world of the presence of God's Kingdom.

Your way of living and working can vividly express full belonging to the one Lord; placing yourselves without reserve in the hands of Christ and of the Church is a strong and clear proclamation of God's presence in a language understandable to our contemporaries. This is the first service that the consecrated life offers to the Church and to the world. Consecrated persons are like watchmen among the People of God who perceive and proclaim the new life already present in our history.

I now address you in a special way, dear brothers and sisters who have embraced the vocation of special consecration, to greet you with affection and thank you warmly for your presence.

I extend a special greeting to Archbishop Franc Rodé, Prefect of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, and to his collaborators who are concelebrating with me at this Holy Mass.

May the Lord renew in you and in all consecrated people each day the joyful response to his freely given and faithful love. Dear brothers and sisters, like lighted candles, always and everywhere shine with the love of Christ, Light of the world. May Mary Most Holy, the consecrated Woman, help you to live to the full your special vocation and mission in the Church for the world's salvation.

Amen!

[Pope Benedict, homily 2 February 2006]

1. Lumen ad revelationem gentium: a light for revelation to the Gentiles (cf. Lk 2:32).

Forty days after his birth, Jesus was taken by Mary and Joseph to the temple to be presented to the Lord (cf. Lk 2:22), according to what the law of Moses prescribes: “Every first-born male shall be consecrated to the Lord” (Lk 2:23); and to offer in sacrifice “a pair of turtle doves or two young pigeons, in accord with the dictate in the law of the Lord” (Lk 2:24).

In recalling these events, the liturgy intentionally and precisely follows the sequence of Gospel events: the completion of the 40 days following Christ’s birth. It does the same, later, with regard to the period between the Resurrection and the Ascension into heaven.

Three basic elements can be seen in the Gospel event celebrated today: the mystery of the coming, the reality of the meeting and the proclamation of the prophecy.

2. First of all, the mystery of the coming. The biblical readings we have heard stress the extraordinary nature of God’s coming: the prophet Malachi announces it in a transport of joy, the responsorial psalm sings it and Luke's Gospel text describes it. We need only listen, for example, to the responsorial psalm: “Lift up, O gates, your lintels ... that the king of glory may come in! Who is this king of glory? The Lord, strong and mighty, the Lord, mighty in battle.... The Lord of hosts, he is the king of glory” (Ps 23 [24]:7-8;10).

He who had been awaited for centuries enters the temple of Jerusalem, he who fulfils the promise of the Old Covenant: the Messiah foretold. The psalmist calls him “the king of glory”. Only later will it become clear that his kingdom is not of this world (cf. Jn 18:36) and that those who belong to this world are not preparing a royal crown for him, but a crown of thorns.

However, the liturgy looks beyond. In that 40-day-old infant it sees the “light” destined to illumine the nations, and presents him as the “glory” of the people of Israel (cf. Lk 2:32). It is he who must conquer death, as the Letter to the Hebrews proclaims, explaining the mystery of the Incarnation and Redemption: “Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same nature” (Heb 2:14), having taken on human nature.

After describing the mystery of the Incarnation, the author of the Letter to the Hebrews presents the mystery of Redemption: “Therefore he had to be made like his brethren in every respect, so that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God, to make expiation for the sins of the people. For because he himself has suffered and been tempted, he is able to help those who are tempted” (ibid., 2:17-18). This is a deep and moving presentation of the mystery of Christ. The passage from the Letter to the Hebrews helps us to understand better why this coming to Jerusalem of Mary’s newborn Son should be a decisive event in the history of salvation. Since it had been built, the temple was awaiting in a most exceptional way the One who had been promised. Thus his coming has a priestly meaning: “Ecce sacerdos magnus”; behold, the true and eternal High Priest enters the temple.

3. The second characteristic element of today’s celebration is the reality of the meeting. Even if no one was waiting for Joseph and Mary when they arrived hidden among the people at the temple in Jerusalem with the baby Jesus, something most unusual occurs. Here they meet persons guided by the Holy Spirit: the elderly Simeon of whom St Luke writes: “This man was righteous and devout, looking for the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit was upon him and it had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he should not see death before he had seen the Lord's Christ” (Lk 2:25-26), and the prophetess Anna, who had lived “with her husband seven years from her virginity, and as a widow till she was eighty-four. She did not depart from the temple, worshiping with fasting and prayer night and day” (Lk 2:36-37). The Evangelist continues: “And coming up at that very hour, she gave thanks to God, and spoke of him to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem” (Lk 2:38).

Simeon and Anna: a man and a woman, representatives of the Old Covenant, who, in a certain sense, had lived their whole lives for the moment when the temple of Jerusalem would be visited by the expected Messiah. Simeon and Anna understand that the moment has come at last, and reassured by the meeting, they can face the last phase of their life with peaceful hearts: “Lord, now let your servant depart in peace, according to your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation” (Lk 2:29-30).

At this discreet encounter, the words and actions effectively express the reality of the event taking place. The coming of the Messiah has not passed unobserved. It was recognized through the penetrating gaze of faith, which the elderly Simeon expresses in his moving words.

4. The third element that appears in this feast is prophecy: today truly prophetic words resound. Every day the Liturgy of the Hours ends the day with Simeon's inspired canticle: “Lord, now let your servant depart in peace, according to your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation, ... a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and for the glory of your people Israel” (Lk 2:29-32).

The elderly Simeon adds, turning to Mary: “Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign that is spoken against (and a sword will pierce through your own soul also), that thoughts out of many hearts may be revealed” (Lk 2:34-35).

Thus while we are still at the dawn of Jesus’ life, we are already oriented to Calvary. It is on the Cross that Jesus will be definitively confirmed as a sign of contradiction, and it is there that his Mother’s heart will be pierced by the sword of sorrow. We are told it all from the beginning, on the 40th day after Jesus’ birth, on the feast of the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, so important in the Church’s liturgy.

5. Dear brothers and sisters, today’s feast is enriched this year with a new significance. In fact, for the first time we are celebrating the Day for Consecrated Life.

Dear men and women religious and you, dear brothers and sisters, members of secular institutes and societies of apostolic life, you are all entrusted with the task of proclaiming, by word and example, the primacy of the Absolute over every human reality. This is an urgent task in our time, which often seems to have lost the genuine sense of God. As I recalled in the Message I addressed to you for this first Day for Consecrated Life: “Truly there is great urgency that the consecrated life show itself ever more ‘full of joy and of the Holy Spirit’, that it forge ahead dynamically in the paths of mission, that it be backed up by the strength of lived witness, because ‘modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and ‘if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses’ (Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii nuntiandi, n. 41)” (L'Osservatore Romano English edition, 29 January 1997, p. 3).

Together with the elderly Simeon and the prophetess Anna, let us go to meet the Lord in his temple. Let us welcome the light of his Revelation, committing ourselves to spreading it among our brothers and sisters in view of the now imminent Great Jubilee of the Year 2000.

May the Blessed Virgin,

Mother of hope and joy,

accompany us

and grant that all believers

may be witnesses to the salvation

which God has prepared in the presence of all peoples

in his incarnate Son, Jesus Christ,

a light for revelation to the Gentiles

and for the glory of his people Israel.

Amen!

[Pope John Paul II, homily 2 February 1997]

Simeon, writes St Luke, "was waiting for the consolation of Israel" (Lk 2:25). Going up to the temple, while Mary and Joseph carry Jesus, he welcomes the Messiah in his arms. Recognising in the Child the light that has come to enlighten the nations is a man now old, who has waited patiently for the fulfilment of the Lord's promises. He has waited patiently.