First Lent Sunday [22 February 2026]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. I apologise if I dwell too long today on the presentation of the texts, but it is central to Christian life to understand in depth the drama of Genesis (first reading), which St Paul takes up in the second reading, bringing it to full understanding. Similarly, the responsorial psalm can be understood starting from the drama recounted in Genesis chapter 3, and likewise the Gospel shows us how to react in order to live in the kingdom of God already on this earth. In my opinion, it is a vision of life that must be clearly focused in order to understand the drama of the practical and often unconscious rejection of God that is consummated in the world in the face of the crucial question: why is there evil in the world? Why does God not destroy it?

Have a good Lent.

*First Reading from the Book of Genesis (2:7-9; 3:1-7a)

In the first chapters of Genesis, two different figures of man appear: the first who lives happily in complete harmony with God and with woman. and creation (chap. 2), and then the man who claims his autonomy by taking for himself the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (chap. 3). Jesus sums up in himself 'all our weaknesses' (Heb 4:15), and, put to the test, he will be the sign of the new humanity: 'the last Adam became a life-giving spirit' (1 Cor 15:45). Before tackling this text, we must remember that its author never claimed to be a historian. The Bible was written neither by scientists nor by historians, but by believers for believers. The theologian who wrote these lines, probably at the time of Solomon in the 10th century BC, seeks to answer the questions that everyone asks: why evil? Why death? Why misunderstandings between couples? Why is life so difficult? Why is work so tiring? Why is nature sometimes hostile? To answer these questions, he draws on a certainty shared by his entire people: the goodness of God. God freed us from Egypt; God wants us to be free and happy. Since the famous exodus from Egypt, led by Moses, and the crossing of the desert, during which God's presence and support were experienced at every new difficulty, there can be no doubt about this. The story we have just read is therefore based on this certainty of God's benevolence and seeks to answer all our questions about evil in the world. With a good and benevolent God, how is it possible that evil exists? Our author has invented a parable to enlighten us: a garden of delights (this is the meaning of the word 'Eden') and humanity represented by a couple charged with cultivating and caring for the garden. The garden is full of trees, each more attractive than the next. The one in the middle is called the 'tree of life'; its fruit can be eaten like all the others. But somewhere in the garden – the text does not specify where – there is another tree, whose fruit is forbidden. It is called the 'tree of the knowledge of what makes one happy or unhappy'. Faced with this prohibition, the couple can have two attitudes: either to trust, knowing that God is only benevolence, and rejoice in having access to the tree of life; if God forbids us the other tree, it is because it is not good for us. Or they can suspect God of having evil intentions, imagining that he wants to prevent us from accessing knowledge. This is the serpent's argument: he addresses the woman and feigns understanding: 'So, did God really say, "You must not eat from any tree in the garden"?' (3:1). The woman replies: "We may eat the fruit of the trees in the garden, but God has said, 'You must not eat the fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden, nor touch it, or you will die'" (3:2-4) . Have you noticed the shift: simply because she has listened to the voice of suspicion, she now speaks only of that tree and says 'the tree in the middle of the garden'; now, in good faith, she no longer sees the tree of life in the centre of the garden, but the tree 'of the knowledge of what makes one happy or unhappy'. Her gaze is already altered, simply because she has allowed the serpent to speak to her; then the serpent can continue its slow work of demolition: "No, you will not die at all! Indeed, God knows that on the day you eat of it, your eyes will be opened and you will be like God, knowing good and evil" (3:5). Once again, the woman listens too well to these beautiful words, and the text suggests that her gaze is increasingly distorted: 'The woman saw that the tree was good for food, pleasing to the eye, and desirable for gaining wisdom' (3:6). The serpent has won: the woman takes the fruit, eats it, gives it to her husband, and he eats it too. And so the story ends: "Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked" (v. 7). The serpent had spoken well: "your eyes will be opened" (3:5); the woman's mistake was to believe that he was speaking in her interest and revealing God's evil intentions. It was nothing but a lie: her gaze changed, it is true, but it became distorted. It is no coincidence that the suspicion cast on God is represented by the features of a serpent: Israel, in the desert, had experienced poisonous snakes. Our theologian at Solomon's court recalls this painful experience and says: there is a poison more serious than that of the most poisonous snakes; the suspicion cast on God is a deadly poison, it poisons our lives. The idea of our anonymous theologian is that all our misfortunes come from this suspicion that corrodes humanity. To say that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is reserved for God is to say that only God knows what makes us happy or unhappy; which, after all, is logical if he is the one who created us. Wanting to eat the fruit of this forbidden tree at all costs means claiming to determine for ourselves what is good for us: the warning 'You must not eat it and you must not touch it, otherwise you will die' clearly indicated that this was the wrong path to take.

But wait! The story goes even further: during the journey through the desert, God gave the Law (the Torah) which from then on had to be observed, what we call the commandments. We know that the daily practice of this Law is the condition for the survival and harmonious growth of this people; if we truly knew that God only wants our life, our happiness, our freedom, we would trust and obey the Law with a good heart. It is truly the "tree of life" made available to us by God.

I said at the beginning that this is a parable, but it is a parable whose lesson applies to each of us; since the world began, it has always been the same story. St Paul (whom we read this Sunday in the second reading) continues his meditation and says: only Christ trusted the Father in everything; he shows us the way of Life.

Note: In the Hebrew text, the serpent's question is deliberately ambiguous: 'Did God really say, "You shall not eat of any tree in the garden"? 'הֲכִי־אָמַר אֱלֹהִים לֹא תֹאכְלוּ מִכֹּל עֵץ הַגָּן? " Ha-ki amar Elohim lo tochlu mikol etz ha-gan? Put this way, the question can be understood in a restrictive sense: "Did God really say, 'You shall not eat of any tree in the garden'?" interpreting "all trees" as a total negation. Or in a general and colloquial sense: "Did God really say, 'You shall not eat of any tree in the garden'?" interpreting "all" in an absolute sense, or as all trees except one, the tree of life or the other of the knowledge of good and evil. The serpent uses this ambiguity to sow doubt and suspicion, insinuating that God might be lying or withholding something good. In the oldest Hebrew manuscripts, there are no punctuation marks as we know them today, so the play on words and the double meaning were intentionally stronger. Exegetes note that the serpent does not make a clear statement but forms a subtle question that shifts the focus to doubt: "Perhaps God is deceiving you?" This account in Genesis has many resonances in the meditation of the people of Israel. One of the reflections suggested by the text concerns the tree of life: planted in the middle of the garden of Eden, it was accessible to man and its fruit was permitted. One might think that its fruit allowed man to remain alive, to that spiritual life that God had breathed into him: "The Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground, breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being" (Gen 2:7). The rabbis then made the connection with the Law given by God on Sinai. In fact, it is accepted by believers as a gift from God, a support for daily life: 'My son, do not forget my teaching, but keep my commands in your heart, for they will prolong your life and bring you peace' (Pr 3:1-2). .

NB For further clarification, I would add this: There is the first prohibition: the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in Genesis 2:16-17, God sets only one limit on man: "Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil thou shalt not eat." The tree of life is not forbidden at this point. The prohibition concerns only the tree of the knowledge of good and evil because God is the one who decides what is good and what is evil, and man is called to trust, not to replace God. Eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge means saying, 'I do not trust God; I decide what is good and what is evil'. After sin, there is a second prohibition (the tree of life) because the situation changes radically. In Genesis 3:22-24, we read: 'Now, lest he reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life and eat, and live forever'. Only after sin does God prevent access to the tree of life. Why? Because man, separated from God by sin, cannot live forever like this. Living eternally with the consequences of sin would be a condemnation, not a gift. God therefore protects man from a distorted immortality. In other words, God does not take life away as punishment, but to prevent evil from becoming eternal.

*Responsorial Psalm (50/51)

"Have mercy on me, O God, in your love; according to your great mercy, blot out my sin. Wash me completely from my guilt, purify me from my offence." The people of Israel are gathered for a great penitential celebration in the Temple of Jerusalem. They recognise themselves as sinners, but they also know God's inexhaustible mercy. After all, if they are gathered to ask for forgiveness, it is because they already know in advance that forgiveness has been granted. This, let us remember, was King David's great discovery: David took Bathsheba, with whom he had fallen in love, and had her husband Uriah killed, because a few days later, Bathsheba was expecting a child by him. When the prophet Nathan went to David, he did not first seek a word of repentance from him; instead, he began by reminding him of all God's gifts and announcing his forgiveness, even before David had had time to make the slightest confession (2 Sam 12). In essence, he said to him, 'Look at all that God has given you... well, know that he is ready to give you anything else you want!'. And a thousand times throughout its history, Israel has been able to verify that God is truly 'the merciful and compassionate Lord, slow to anger and rich in love and faithfulness', according to the revelation he granted to Moses in the desert (Ex 34:6). The prophets also transmitted this message, and the few verses of the psalm we have just heard are full of these discoveries of Isaiah and Ezekiel. Isaiah, for example: "It is I, I who blot out your transgressions for my own sake, and I will not remember your sins" (Is 43:25); or again: "I have blotted out your transgressions like a cloud and your sins like mist. Return to me, for I have redeemed you" (Is 44:22).

This proclamation of God's gratuitous forgiveness sometimes surprises us: it seems too good, perhaps; for some it even seems unfair: if everything is forgivable, what is the point of making an effort? Perhaps we are too quick to forget that we all, without exception, need God's mercy; so let us not complain about it! And let us not be surprised if God surprises us, for, as Isaiah says, "God's thoughts are not our thoughts". And Isaiah himself points out that it is above all in the matter of forgiveness that God surprises us most. The only condition required is to recognise ourselves as sinners. When the prodigal son (Lk 15) returns to his father, for reasons that are not very noble, Jesus puts a phrase from Psalm 50 on his lips: "Against you, against you alone, have I sinned," and this simple phrase restores the bond that the ungrateful young man had broken. Faced with this ever-renewed proclamation of God's mercy, the people of Israel — for it is they who speak here, as in all the psalms — recognise themselves as sinners: the confession is not detailed, as it never is in the penitential psalms, but the essential is said in this plea: "Have mercy on me, O God, in your love, according to your great mercy, blot out my sin... And God, who is all mercy, that is, as if drawn by misery, expects nothing more than this simple recognition of our poverty. The word "mercy" has the same root as the word "alms": literally, we are beggars before God. Two things remain to be done. First of all, simply give thanks for the forgiveness granted without ceasing; the praise that the people of Israel address to God is the recognition of the goodness with which he has filled them since the beginning of their history. This clearly shows that the most important prayer in a penitential celebration is thanksgiving for God's gifts and forgiveness: we must begin by contemplating Him, and only then, when this contemplation has revealed to us the gap between Him and us, can we recognise ourselves as sinners. The ritual of reconciliation says this clearly in its introduction: 'We confess God's love together with our sin'. And the song of gratitude will flow spontaneously from our lips: we need only allow God to open our hearts. "Lord, open my lips, and my mouth shall proclaim your praise"; some recognise here the first sentence of the Liturgy of the Hours each morning; in fact, it is taken from Psalm 50/51. This alone is a true lesson: praise and gratitude can only arise in us if God opens our hearts and our lips. St Paul puts it another way: 'God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, "Abba!", that is, "Father!"' (Gal 4:6). This irresistibly brings to mind a gesture of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark: the healing of a deaf-mute; touching his ears and tongue, Jesus said, 'Ephphatha', which means 'Be opened'. And then, spontaneously, those present applied to Jesus a phrase that the Bible reserved for God: "He makes the deaf hear and the mute speak" (cf. Is 35:5-6). Even today, in some baptismal celebrations, the celebrant repeats this gesture of Jesus on the baptised, saying: "The Lord Jesus has made the deaf hear and the mute speak; may he grant you to hear his word and proclaim your faith, to the praise and glory of God the Father". The second thing to do, and what God expects of us, is to forgive in turn, without delay or conditions... and this is a serious undertaking in our lives.

*Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Romans (5:12-19)

Adam was a figure of the one who was to come, Paul tells us; he speaks of Adam in the past tense because he refers to the book of Genesis and the story of the forbidden fruit, but for him Adam's drama is not a story of the past: this story is ours, every day; we are all Adam at times; the rabbis say, 'everyone is Adam to himself'.

And if we were to summarise the story of the Garden of Eden (which we reread in this Sunday's first reading), we could say this: by listening to the voice of the serpent rather than God's command, by allowing suspicion about God's intentions to invade their hearts, by believing that they could allow themselves everything, that they could 'know' everything - as the Bible says — man and woman placed themselves under the dominion of death. And when we say, 'everyone is Adam to himself', it means that every time we turn away from God, we allow the powers of death to invade our lives. St Paul, in his letter to the Romans, continues the same meditation and announces that humanity has taken a decisive step in Jesus Christ; we are all brothers and sisters of Adam and we are all brothers and sisters of Jesus Christ; we are brothers and sisters of Adam when we allow the poison of suspicion to infest our hearts, when we presume to make ourselves the law. We are brothers and sisters of Christ when we trust God enough to let him guide our lives. We are under the dominion of death when we behave like Adam; when we behave like Jesus, that is, like him, 'obedient' (i.e. trusting), we are already resurrected in the kingdom of life, the one John speaks of: 'He who believes in me, even if he dies, will live', a life that biological death does not interrupt. Let us return to the account in the Book of Genesis: The Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground; he breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being. This breath of God that makes man a living being – as the text says – was not given to animals: yet they are very much alive in a biological sense; we can therefore deduce that man enjoys a life different from biological life. St Paul affirms that because of Adam, death has reigned: he uses the terms 'reign' and 'reign over' several times, showing that there are two kingdoms that confront each other: the kingdom of sin when humanity acts like Adam, which brings death, judgement and condemnation. Then there is the kingdom of Christ, that is, with him, the new humanity, which is the kingdom of grace, of life, of free gift, of justification. However, no man is entirely in the kingdom of Christ, and Paul himself recognises this: 'I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want' (Rom 7:19). . Adam, that is, humanity, was created to be king, to cultivate and keep the garden, as we read in the book of Genesis, but, ill-advised by the serpent, he wants to do everything by himself, with his own strength, cutting himself off from God. Jesus Christ, on the contrary, does not 'claim' this kingship: it is given to him. As Paul writes in his letter to the Philippians: "though he was in the form of God, he did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself" (2:6, NRSV). The story of the Garden of Eden says the same thing in images: before the Fall, man and woman could eat the fruit of the tree of life; after the Fall, they no longer have access to it. Each in its own way, these two texts – that of Genesis on the one hand and that of the letter to the Romans on the other – tell us the deepest truth of our lives: with God, everything is grace, everything is a free gift; and Paul here insists on the abundance, on the profusion of grace, even speaking of the 'disproportion' of grace: It is not like the fall, the free gift... much more, God's grace has been poured out in abundance on the multitude, this grace given in one man, Jesus Christ. Everything is a gift, and this is not surprising since, as St John says, God is Love. It is not because Christ behaved well that he received a reward, and Adam received punishment because of his misconduct. Paul's discourse is deeper: Christ lives in total trust that everything will be given to him in God... and everything is given to him in the Resurrection. Adam, that is, each one of us, often wants to take possession of what can only be received as a gift, and for this reason finds himself 'naked', that is, deprived of everything. We could say that by birth we are citizens of the kingdom of Adam; through baptism we have asked to be naturalised in the kingdom of Christ. Obedience and disobedience in Paul's sense could thus be replaced: 'obedience' with trust and 'disobedience' with mistrust; as Kierkegaard says: "The opposite of sin is not virtue; the opposite of sin is faith." If we reread the story of Genesis, we can see that the author intentionally did not give proper names to the man and woman; he spoke of Adam (derived from adamah, meaning earth, dust), which means 'human being taken from the earth', while Eve (derived from Chavah, meaning life) is the one who gives life. By not giving them names, he wanted us to understand that the drama of Adam and Eve is not the story of particular individuals, but the story of every human being, and has always been so.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (4:1-11)

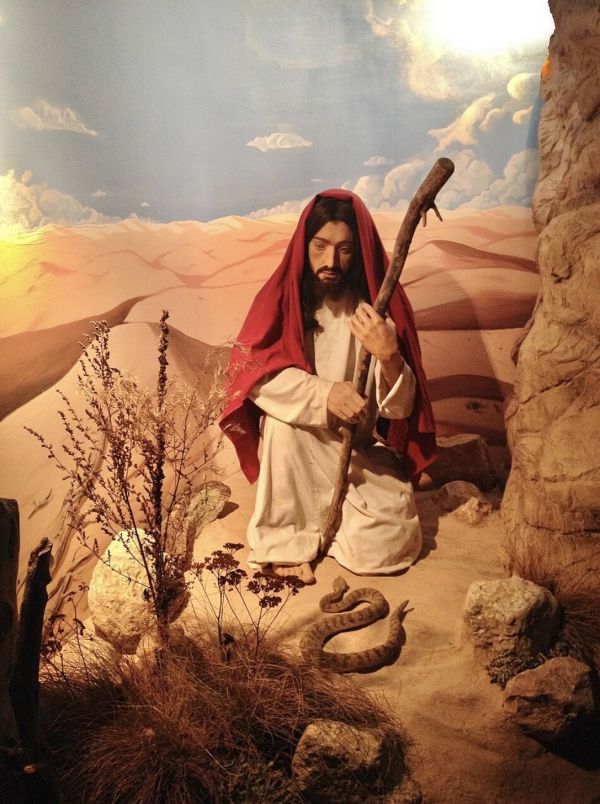

Every year, Lent begins with the story of Jesus' temptations in the desert: we must believe that this is a truly fundamental text! This year we read it according to St Matthew. After recounting the baptism of Jesus, Matthew immediately continues: "Jesus was led by the Spirit into the desert to be tempted by the devil" . The evangelist thus invites us to make a connection between Jesus' baptism and the temptations that immediately follow. Matthew had said a few verses earlier: Jesus "will save his people from their sins", which is precisely the meaning of the name Jesus. John the Baptist baptises Jesus in the Jordan even though he did not agree and had said: " I need to be baptised by you, and yet you come to me!" (Mt 3:14)... And it came to pass that when Jesus came up out of the water after his baptism, the heavens opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and coming upon him. And a voice came from heaven, saying, "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased."

This phrase alone publicly announces that Jesus is truly the Messiah: because the expression 'Son of God' was synonymous with King-Messiah, and the phrase 'the beloved, in whom I am well pleased' (3:17) refers to one of the songs of the Servant in Isaiah. In a few words, Matthew reminds us of the whole mystery of the person of Jesus; and it is he, precisely, who is the Messiah, the Saviour, the Servant who will confront the Tempter. Like his people a few centuries earlier, he is led into the desert; like his people, he knows hunger; like his people, he must discover what God's will is for his children; like his people, he must choose before whom to bow down. "If you are the Son of God," repeats the Tempter, thus revealing the real problem; and Jesus is confronted with it, not only three times, but throughout his earthly life. What does it mean, in concrete terms, to be the Messiah? The question takes various forms: solving people's problems with miracles, such as turning stones into bread? Provoking God to test his promises? ... By throwing himself from the temple, for example, because Psalm 91 promised that God would rescue his Messiah... Possessing the world, dominating, reigning at any cost, even worshipping any idol? Even ceasing to be the Son? It should be noted that in the third temptation, the Tempter no longer repeats "If you are the Son of God".

The culmination of these temptations is that they target God's promises: they promise nothing more than what God himself promised to his Messiah. And the two interlocutors, the Tempter and Jesus, know this well. But here's the thing... God's promises are in the order of love; they can only be received as gifts; love cannot be demanded, it cannot be seized, it is received on bended knee, with gratitude. Ultimately, the same thing happens as in the Garden of Genesis: Adam knows, and rightly so, that he was created to be king, to be free, to be master of creation; but instead of accepting gifts as gifts, with gratitude and appreciation, he demands, he claims, he places himself on a par with God... He leaves the order of love and can no longer receive the love offered... he finds himself poor and naked. Jesus makes the opposite choice: 'Get behind me, Satan!' as he once said to Peter, adding, 'Your thoughts are not those of God, but those of men' (Mt 16:23). Furthermore, several times in this text, Matthew calls the Tempter "devil," which in Greek means "the one who divides." Satan is for each of us, as he is for Jesus himself, the one who tends to separate us from God, to see things in Adam's way and not in God's way. On closer inspection, it all lies in the gaze: Adam's is distorted; to keep his gaze clear, Jesus scrutinises the Word of God: the three responses to the Tempter are quotations from the book of Deuteronomy (chapter 8), in a passage that is precisely a meditation on the temptations of the people of Israel in the desert. Then, Matthew points out, the devil (the divider) leaves him; he has not succeeded in dividing, in turning away the Son's heart. This recalls St John's phrase in the Prologue (Jn 1:1): 'In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God (pros ton Theon, which means turned towards God), and the Word was God'. . The devil has not succeeded in turning the Son's heart away, and so he is then completely available to receive God's gifts: "Behold, angels came and ministered to him."

NB At the request of some, I would also like to present the homily I am preparing for this first Sunday of Lent.

Homily – First Sunday of Lent

Every year, Lent begins with the story of Jesus' temptations in the desert: we must believe that this is a truly fundamental text! This year we read it according to St Matthew. After recounting the baptism of Jesus, Matthew immediately continues: "Jesus was led by the Spirit into the desert to be tempted by the devil." The evangelist thus invites us to make a connection between the baptism of Jesus and the temptations that immediately follow. When Jesus came up out of the water, the heavens opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and coming upon him. And a voice came from heaven, saying, 'This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased'. Jesus is the 'Son of God', the Messiah, the Saviour, the servant of God who will face the Tempter. Satan will say just that: "If you are the Son of God," thus revealing the real problem, which is the attempt to separate Jesus' divine identity from his way of living it, or better yet, to push Jesus to use his divine power without the trust of a son and his humanity without obedience. To understand this better, we must return to the first reading from the book of Genesis, where the tempting serpent promises Eve: "You will be like God" (Gen 3:5). The temptation is not only about a fruit that should not be eaten, but about autonomy from God, the desire to decide for oneself what is good and evil, without trusting the Father. Adam and Eve allowed themselves to be persuaded and found themselves naked. They lost everything!

In the desert, the devil now tempts Jesus, the new Adam, a true man like us except for sin, and launches three provocations: 1. "Say that these stones become bread." The temptation to live without depending on God, to seek immediate satisfaction. There is a hunger that goes beyond bread and that only God can satisfy. But this means trusting God, and Jesus responds: 'It is written: Man shall not live by bread alone' (Mt 4:4). 2nd temptation. The devil raises the stakes: "Throw yourself down" from the temple and the angels will catch you. Here is the temptation to manipulate God, to ask for spectacular signs to confirm one's faith. This is a very subtle temptation today, but one that is very common when we believe in making the liturgy, evangelisation and ecclesial events spectacular. Jesus teaches us to spread the Gospel like yeast in dough and a small seed in the ground: everything happens in silence because we must not believe that we are protagonists but lives always hidden in God, even when we act publicly. It is not our work to convert the world. Let us listen to Jesus who replies: "It is written: You shall not tempt the Lord your God" (Mt 4:7). . 3. In the third temptation, it should be noted that the Tempter no longer repeats 'If you are the Son of God', because Satan believes himself to be the master of the world and so he can say to him, 'I will give you everything if you bow down to me'. It is the temptation of power and compromise, of bending one's life to immediate advantages. It is very dangerous because it often involves the idea that we can accept anything in order to evangelise, but we are not the masters! Jesus replies: "It is written: You shall worship the Lord your God and him alone shall you serve" (Mt 4:10).

Let us note something decisive: Jesus does not respond with his own intelligence or strength, but always by referring to the Word of God, which is the only true light that can guide man's journey through the desert of life, a journey that is often dark and full of pitfalls. This is because the Word of God is the light of truth that never goes out. St John Chrysostom reminds us: "In Scripture we find not only words, but the strength we need to overcome evil; it is the nourishment of the soul and the light that guides those who walk in darkness" (Homilies on Matthew, 4th century). Even when the world rejects God, even when the right choices seem uncomfortable or losing, Scripture remains the sure guide. How can we apply this to our lives? Today, being a Christian is often difficult: faith can be mocked or ignored, the Gospel seems useless, Christ is fought against and sometimes tolerated, but not welcomed. Lent invites us to make a daily choice: who guides our lives? Do we want to do everything on our own, like Eve and Adam in Eden, choosing what seems most convenient? Or do we entrust ourselves to God, allowing his Word to enlighten our decisions and give meaning even to our difficulties? Following Christ means choosing fidelity, even when the world goes against it. It means living our lives as Christians without compromise, basing ourselves not on personal strength, but on the living Word of God. We are always sustained by a certain and concrete hope: the Gospel ends with a silent promise: 'Then the devil left him' (Mt 4:11). Those who entrust themselves to God are not left alone in their trials. Temptation may seem powerful, but those who walk in the light of the Word are never defeated.

+Giovanni D’Ercole