don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Samaritan woman, weary at the well. Or Jesus, fresh Spring within reach. Assent Faith, Bridal Faith, Faith Trigger, Faith Astonishment

Second Sunday in Lent

Second Lent Sunday (year A) [1st March 2026]

*First Reading from the Book of Genesis (12:1-4)

The few lines we have just read constitute the first act of the entire adventure of our faith: the faith of the Jews, then, in chronological order, of Christians and Muslims. We are in the second millennium BC. Abram* lived in Chaldea, that is, in Iraq, and more precisely in the extreme south-east of Iraq, in the city of UR, in the Euphrates valley, near the Persian Gulf. He lived with his wife Sarai, his father Terah, his brothers (Nahor and Aran) and his nephew Lot. Abram was seventy-five years old, his wife Sarai sixty-five; they had no children and, given their age, would never have any. One day, his old father, Terah, set out on the road with Abram, Sarai and his nephew Lot. The caravan travelled up the Euphrates valley from the south-east to the north-west with the intention of then descending towards the land of Canaan. There was a shorter route, of course, connecting the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, but it crossed a huge desert. Terah and Abram preferred to travel along the 'Fertile Crescent', which lives up to its name. The last stop in the north-west is called Harran. It is there that old Terah dies. And it is above all there that, for the first time, about 4000 years ago, around 1850 BC, God spoke to Abram.

"Leave your land," says our liturgical translation, but it omits the first two words, probably to avoid excessive interpretations, which have not always been avoided. In fact, in Hebrew, the first two words are "You, go!" Grammatically, they mean nothing else. It is a personal appeal, a setting aside: it is a true story of vocation. And it is to this simple invitation that Abram responded. It is often translated as "Go for yourself," but this is already an over-interpretation of faith. "Go for yourself": we must be aware that we are moving away from the literal meaning of the text and entering into an interpretation, a spiritual commentary. It is Rashi, the great 11th-century Jewish commentator (in Troyes in Champagne), who translates "Go for yourself, for your own good and for your happiness". In fact, this is what Abram will experience in the course of the days. If God calls man, it is for man's own good, not for anything else! God's merciful plan for humanity is contained in these two little words: 'for you'. God already reveals himself as the one who desires the good of man, of all men**; if there is one thing to remember, it is this! 'Go for yourself': a believer is someone who knows that, whatever happens, God is leading him towards his fulfilment, towards his happiness. So here are God's first words to Abram, the words that set off his whole adventure... and ours! Go, leave your country, your family and your father's house, and go to the land that I will show you. And what follows are only promises: I will make you a great nation, I will bless you, I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing... All the families of the earth shall be blessed in you. Abram is torn from his natural destiny, chosen, elected by God, invested with a universal vocation. Abram, for the moment, is a nomad, perhaps rich, but unknown, and he has no children; his wife Sarai is well past childbearing age. Yet it is he whom God chooses to become the father of a great people. This is what that 'for you' meant earlier: God promises him everything that, at that time, constitutes a man's happiness: numerous descendants and God's blessing. But this happiness promised to Abram is not only for him: in the Bible, no vocation, no calling is ever for the selfish interest of the one who is called. This is one of the criteria of an authentic vocation: every vocation is always for a mission in the service of others. Here is this phrase: 'In you all the families of the earth shall be blessed'. It means at least two things: first, your success will be such that you will be taken as an example: when people want to wish someone happiness, they will say, 'May you be as happy as Abram'. Second, this 'in you' can mean through you; and then it means 'through you, I, God, will bless all the families of the earth'. God's plan for happiness passes through Abram, but it surpasses him, it overflows him; it concerns all humanity: 'In you, through you, all the families of the earth will be blessed'. Throughout the history of Israel, the Bible will remain faithful to this first discovery: Abraham and his descendants are the chosen people, chosen by God but for the benefit of all humanity, from the first day, from the first word to Abraham. The fact remains that other nations are free not to enter into this blessing; this is the meaning of the seemingly curious phrase: "I will bless those who bless you, and those who curse you I will curse" (12:3). It is a way of expressing our freedom: anyone who wishes to do so can share in the blessing promised to Abram, but no one is obliged to accept it! The time for the great departure has come; the text is extraordinary in its sobriety: it simply says, "Abram departed as the Lord had commanded him" (12:4), and Lot went with him. One cannot be more laconic! This departure, at the simple call of God, is the most beautiful proof of faith; four thousand years later, we can say that our faith finds its source in that of Abraham; and if our whole lives are illuminated by faith, it is thanks to him! And all human history becomes the place of the fulfilment of God's promises to Abraham: a slow, progressive fulfilment, but certain and sure.

Notes: *At the beginning of this great adventure, the man we call Abraham was still called only Abram; later, after years of pilgrimage, he would receive from God the new name by which we know him: Abraham, which means 'father of multitudes'.

**This 'for you' should not be understood as exclusive, even if it was not immediately understood at first. Only after a long discovery of God's Covenant were believers able to access the full truth: God's plan concerns not only Abraham and his descendants, but all of humanity. This is what we call the universality of God's plan. This discovery dates back to the Exile in Babylon in the 6th century BC.

Addition: At another point in Abraham's life, when he offers Isaac as a sacrifice, God uses the same expression, "Go," to give him the strength to face the trial, reminding him of the journey he has already made. The Letter to the Hebrews takes Abraham's departure to explain what faith is (cf. Heb 11:8-12).

*Responsorial Psalm (32/33)

The word 'love' appears three times in these few verses, and this insistence responds very well to the first reading: Abraham is the first in all human history to discover that God is love and that he has plans for the happiness of humanity. However, it was necessary to believe in this extraordinary revelation. And Abraham believed, he agreed to trust in the words of the future that God announced to him. An old man without children, yet he would have had every reason to doubt this incredible promise from God. God says to him: Leave your country... I will make you a great nation. And the text of Genesis concludes that Abram left as the Lord had told him.

This is a beautiful example for us at the beginning of Lent: we should believe in all circumstances that God has plans for our happiness. This was precisely the meaning of the phrase pronounced over us on Ash Wednesday: "Repent and believe in the Gospel." To convert means to believe once and for all that the Newness is that God is Love. Jeremiah said on behalf of God: 'I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope' (Jer 29:11). Thus, the first two Sundays of Lent invite us to make a choice: on the first Sunday, we read in the book of Genesis the story of Adam: the man who suspects God in the face of a prohibition (not to eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil), imagining that God might even be jealous! These are the insinuations of the serpent, which means poison. For this second Sunday of Lent, however, we read the story of Abraham, the believer. A little further on, the book of Genesis says of him: Abram believed in the Lord, who counted him as righteous. And, to help us follow the same path as Abraham, this psalm suggests words of trust: 'The eye of the Lord is on those who fear him, on those who hope in his love to deliver them from death'. At the beginning, we read: 'The earth is full of love...' and then the expression 'those who fear him' is explained in the next line: 'those who hope in his love', so far from fear, quite the opposite! The temptation is to want to be free and do whatever we want... to obey only ourselves. All this comes from experience, and that is why the chosen people can say: 'the eye of the Lord is on those who fear him, on those who hope in his love' because God has watched over them like a father over his children. When it says that he frees them from death, it is not talking about biological death. We must remember that at the time this psalm was composed, individual death was not considered a tragedy; what mattered was the survival of the people in the certainty that God would keep his people alive. At all times, and especially in times of trial, God accompanies his people and delivers them from death. The reference to times of famine is certainly an allusion to the manna that God sent during the Exodus, when hunger became threatening. All the people can bear witness to this care of God in every age; and when we sing "The word of the Lord is upright, and all his work is done in faithfulness," we are simply repeating the name of the merciful and faithful God who revealed himself to Moses (Ex 34:6). The conclusion is a prayer of trust: "May your love be upon us, Lord, as we hope in you" is an invitation to believers to offer themselves to this love.

*Second reading from the second letter of St Paul the Apostle to Timothy (1:8b-10)

Paul is in prison in Rome, he knows that he will soon be executed, and here he gives his last recommendations to Timothy: "My dear son, with the strength of God, suffer with me for the Gospel." This suffering is the persecution that is inevitable for a true disciple of Christ, as Jesus had said (cf. Mk 8:34-35). Both at the beginning and at the end of the passage, there is a reference to the Gospel, which is presented as an inclusion. In the middle, framed by these two identical references, Paul explains what this Gospel is. He uses the word Gospel in its etymological sense of good news, just as Jesus himself said at the beginning of his preaching in Galilee: "Repent and believe in the Gospel, the Good News" means that Christian preaching is the proclamation that the kingdom of God has finally been inaugurated. For Paul, it is in the central sentence of our text that we discover what the Gospel consists of: ultimately, it can be summed up in a few words: God has saved us through Jesus Christ. *"God saved us": it is a past tense, something that has been accomplished; but at the same time, in order for people to enter into this salvation, it is necessary that the Gospel be proclaimed to them. It is therefore truly a holy vocation that has been entrusted to us: "God saved us and called us to a holy vocation" (1:9). It is a holy vocation because it is entrusted to us by God who is holy; it is a holy vocation because it involves proclaiming God's plan; it is a holy vocation because God's plan needs our collaboration: each of us must play our part, as Paul says. But the expression "holy vocation" also means something else: God's plan for us, for humanity, is so great that it fully deserves this name. The particular vocation of the apostles is part of this universal vocation of humanity.

*"God has saved us": in the Bible, the verb "to save" always means "to liberate". It took a long and gradual discovery of this reality on the part of the people of the Covenant: God wants man to be free and intervenes incessantly to free us from every form of slavery. There are many types of slavery: political slavery, such as servitude in Egypt or exile in Babylon; and each time Israel recognised God's work in its liberation; social slavery, and the Law of Moses, as the prophets never cease to call for the conversion of hearts so that every person may live in dignity and freedom; religious slavery, which is even more insidious. The prophets never ceased to transmit this will of God to see humanity finally freed from all its chains. Paul says that Jesus has freed us even from death: Jesus "has conquered death and brought life and immortality to light through the gospel" (1:10). Paul affirms this

as he prepares to be executed. Jesus himself died, and we too will all die. Jesus, therefore, is not speaking of biological death. What victory is he referring to then? Jesus, filled with the Holy Spirit, gives us his own life, which we can share spiritually, and which nothing can destroy, not even biological death. His Resurrection is proof that biological death cannot destroy it, so for us biological death will be nothing more than a passage towards the light that never sets: in the funeral liturgy we say: "Life is not taken away, but transformed". If biological death is part of our physical constitution, made of dust – as the book of Genesis says – it cannot separate us from Jesus Christ (cf. Rom 8:39). In us there is a relationship with God that nothing, not even biological death, can destroy: this is what St John calls 'eternal life'.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (17:1-9)

"Jesus took Peter, James and John with him": once again we are faced with the mystery of God's choices. It was to Peter that Jesus had said shortly before, in Caesarea: "You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the powers of death will not prevail against it" (Mt 16:18). But Peter is accompanied by two brothers, James and John, the two sons of Zebedee. "And Jesus led them up a high mountain, apart": on a high mountain Moses had received the Revelation of the God of the Covenant and the tablets of the Law; that Law which was to progressively educate the people of the Covenant to live in the love of God and of their brothers and sisters. On the same mountain, Elijah had received the revelation of the God of tenderness in the gentle breeze... Moses and Elijah, the two pillars of the Old Testament... On the high mountain of the Transfiguration, Peter, James and John, the pillars of the Church, receive the revelation of the God of tenderness incarnate in Jesus: "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased". And this revelation is granted to them to strengthen their faith before the storm of the Passion. Peter will write about it later (cf. 2 Pt 1:16-18).

The expression "my beloved Son: listen to him" designates Jesus as the Messiah: to Jewish ears, this simple phrase is a triple allusion to the Old Testament, because it recalls three very different texts, but ones that are well present in everyone's memory; all the more so because the expectation was intense at the time of Jesus' coming and hypotheses were multiplying: we have proof of this in the numerous questions addressed to Jesus in the Gospels. "Son" was the title usually given to kings, and the Messiah was expected to have the characteristics of a king descended from David, who would finally reign on the throne of Jerusalem, which had been without a king for a long time. The beloved, in whom I am well pleased, evoked a completely different context: it refers to the "Songs of the Servant" in the book of Isaiah; it meant that Jesus is the Messiah, no longer in the manner of a king, but of a Servant, in the sense of Isaiah (Is 42:1). 'Listen to him' meant something else: that Jesus is the Messiah-Prophet in the sense that Moses, in the Book of Deuteronomy, had announced to the people: 'The Lord your God will raise up for you, from among your own brothers, a prophet like me; you shall listen to him' (Dt 18:15). ' "Let us make three tents": this phrase of Peter suggests that the episode of the Transfiguration may have taken place during the Feast of Tabernacles, or at least in a climate linked to it, a feast celebrated in memory of the crossing of the desert during the Exodus and the Covenant made with God, in the fervent experience that the prophets would later call the betrothal of the people to the God of tenderness and fidelity. During this feast, people lived in huts for eight days, waiting and imploring a new manifestation of God that would be fulfilled with the coming of the Messiah. On the Mount of Transfiguration, the three apostles suddenly find themselves faced with this revelation of the mystery of Jesus: it is not surprising that they are seized with the fear that grips every man before the manifestation of the holy God. nor is it surprising that Jesus raises them up and reassures them: the Old Testament had already revealed to the people of the Covenant that the most holy God is the God who is close to man and that fear is not appropriate. But the revelation of the mystery of the Messiah, in all its dimensions, is not yet within everyone's reach; Jesus orders them not to tell anyone for the time being, before the Son of Man has risen from the dead. By saying this last sentence, Jesus confirms the revelation that the three disciples have just received: he is truly the Messiah whom the prophet Daniel saw in the form of a man, coming on the clouds of heaven (cf. Dan 7:13-14). Daniel himself presents the Son of Man not as a solitary individual, but as a people, whom he calls "the people of the Most High". The fulfilment is even more beautiful than the promise: in Jesus, Man-God, it is the whole of humanity that will receive this eternal kingship and be eternally transfigured. But Jesus said clearly: Tell no one anything before the Resurrection. Only after Jesus' Resurrection will the apostles be able to bear witness to it.

+Giovanni D'Ercole

Perfection: going all the way. And new Birth

Between intimate struggle and not opposing the evil one

(Mt 5:43-48)

Jesus proclaims that our heart is not made for closed horizons, where incompatibilities are accentuated.

He forbids exclusions, and with it resentments, communication difficulties.

In us there is something more than every facet of opportunism, and instinct to retort blow by blow... to even the score... or close oneself in one's own exemplary group.

In Latin perfĭcĕre means to complete, to lead to perfection, to do completely.

We understand: here it’s essential to introduce other energies; letting mysterious virtues act... between the deepest spaces that belong to us, and the mystery of events.

Otherwise we would assimilate an external integrity model, which doesn’t flow from the Source of being and doesn’t correspond to us in essence.

Within the paradigms of perfection, the captive Uniqueness would no longer know where to go.

Diamonds seem perfect - but nothing is born of them: God's ‘perfect’ ones are those who go ‘all the way’.

Jesus doesn’t want the existence of Faith to be marked by the usual hard extrinsic struggle - made up of intimate lacerations.

There are differences; however He orders to subvert the customs of ancient wisdom and divisions (acceptable or not, friend or foe, near or far, pure and impure, sacred and profane).

The Kingdom of God, that is the community of sons - this sprout of an alternative society - is radically different because it starts from the Seed, not from external gestures; nor does it use sweeteners, to conceal the intimate confrontation.

Events spontaneously regenerate, outside and even within us; useless to force.

The growth and destination continues and will become magnificent, also thanks to the mockery and constraints set up in an adverse way.

Surrendering, giving in, putting down the armor, will make room for new joys.

Fighting what appear to be “adversaries” confuses the soul: it is precisely the stumbles on the intended path that open up and ignite the living space - normally too narrow, suffocated by obligations.

Subtle awareness and perfection that distinguishes the authentic new man in the Spirit from the barker who ignores the things of the Father and seeks laboured shortcuts, by passing favours and 'bribes' in order to immediately settle his business with God and neighbour.

Loving the enemy who [draws us out and] makes us Perfect:

If others are not as we have dreamed of, it’s fortunate: the doors slammed in the face and their goad are preparing us many other joys.

The adventure of extreme Faith is for a wounding Beauty and an abnormal, prominent Happiness.

The ‘win-or-lose’ alternative is false: one must get out of it.

Here, only those who know to wait will find their Way.

To internalize and live the message:

What awareness or purpose do you propose in involving time, perception, listening, kindness? Appear different from your disposition, to please others? Get accepted? Or become perfectly yourself, and wait for the developments that are brewing?

[Saturday 1st wk. in Lent, February 28, 2026]

Perfection: going all the way. And new Birth

Between intimate struggle and not opposing the evil one

(Mt 5:43-48)

In his first encyclical Pope Benedict wrote:

"With the centrality of love, the Christian faith has taken up what was the core of the faith of Israel and at the same time has given this core a new depth and breadth. The believing Israelite, in fact, prays every day with the words of the Book of Deuteronomy, in which he knows that the centre of his existence is enclosed: Listen, Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength' (6:4-5). Jesus united the commandment of love of God with the commandment of love of neighbour, contained in the Book of Leviticus: "You shall love your neighbour as yourself" (19:18; cf. Mk 12:29-31), making it a single precept. Since God loved us first (cf. 1 John 4:10), love is now no longer just a "commandment", but is the response to the gift of love, with which God comes to us.

In a world where the name of God is sometimes linked to vengeance or even the duty of hatred and violence, this is a message of great relevance and very concrete meaning" [Deus Caritas est, n.1].

The "victory-or-defeat" alternative is false: we must come out of it

Jesus proclaims that our heart is not made for closed horizons, where incompatibilities are accentuated.

He forbids exclusion, and with it resentments, difficulties in communication.

There is something more in us than any facet of opportunism, and the instinct to strike back blow after blow... to even the score... even to close oneself within one's own exemplary group.

In Latin perfĭcĕre means to fulfil, to complete, to lead to perfection, to do completely.

We understand it: here it is indispensable to introduce other energies; to let mysterious virtues act... between the deepest spaces that belong to us, and the mystery of events.

How for us to reach the summit of the Mount of the Beatitudes. For a new Birth, a new Beginning.

Impossible, if we do not allow an innate, primordial Wisdom to develop - magmatic, yet far more intact and inapposite.

Venturing away from one's enclosure - even out of the worldly chorus - may not make one original, but it does begin to cure our eccentric exceptionalism.

Otherwise we would assimilate an external model of integrity, which does not spring from the Source of being and does not correspond to us in essence.

Within the paradigms of perfection, the captive uniqueness would no longer know where to go. It would go round in circles believing it would climb [in religion, as on a spiral staircase, which leads to nothing: a typical mechanism of ascetic forms].

In the exasperation of models outside ourselves, we subject the soul to the style of (even ecclesiastical) celebrities.

The anxiety produced by the narrowness of charisma, of champions, of roles lacking deep harmony, will then be ready to attack us; it will present itself around the corner as an invincible adversary.

Perfect seem like diamonds - from which, however, nothing is born: God's perfect are those who go all the way.

The Tao says: 'If you want to be given everything, give up everything'.

"Everything" also means the image we are accustomed to present to others, to be liked at any cost. One has to come out of it.

A transgressive Jesus meets the Wisdom of all times, even the natural one - absolutely not conformist.

He does not want the existence of Faith to be marked by the usual hard extrinsic struggle [typical of the 'spiritual' mentality] made of intimate lacerations.

Even today - unfortunately - in many believing realities, one is still trained in the idea of the inevitable opposition between instincts to life and decent standards.

The Lord glosses over the addictive idea of devout toil, and does so by daring to supplement the ancient Scripture, almost correcting the roots of the civil and venerable identity of the people, identified in the Torah.

Several times and in succession he suggests modifying the sacred and unappealable treasure of the Law: 'It was said [...] Now I say to you'.

The differences are there, yet Jesus commands to subvert the customs of ancient wisdom, the divisions involved: acceptable or not, friends or foes, near or far, pure and impure, sacred and profane; so on.

The Kingdom of God, that is, the community of children - this offshoot of an alternative society - is radically different because it starts from the Seed, not from outward gestures; nor does it use sweeteners, to conceal the intimate clash.

It is not 'new' as the latest of wiles or inventions to be set up.... But because it supplants the whole world of one-sided artifices.

In this way: souls must take the pace of things, to grasp the very rhythm of God, who wisely creates.

Events regenerate spontaneously, outside and even within us; it is useless to force them.

The growth and destination remains and will become magnificent, even through the mockery and constraints set up against it - by the most blatant and insincere exhibitionists, or by those who seem close.

Surrendering, giving in, laying down the armour, will make room for new joys.

Fighting the 'allergists' confuses the soul: it is precisely the stumbling on the intended path that opens and ignites the vital space - normally too narrow, suffocated by obligations.

In the Tao Tê Ching we read: 'If you want to obtain something, you must first allow it to be given to others'.

The blossoming will follow the natural nature of the children: it will be without any effort or recitation of volitional, overburdened holiness (sympathetic or otherwise).

Subtle awareness and Perfection that distinguishes the authentic new man in the Spirit from the barker who ignores the things of the Father and seeks laboured shortcuts, passing favours and 'bribes' in order to immediately settle his affairs with God and neighbour.

Love the enemy who [draws us out and] makes us Perfect:

If others are not as we dreamed, it is fortunate: the doors slammed in our faces and their stinging are preparing other joys for us.

The adventure of extreme Faith is for a Beauty that wounds and an abnormal, prominent Happiness.

Here, only those who know how to wait find their Way.

To internalise and live the message:

What awareness or purpose do you set yourself in engaging time, perception, listening, kindness?

To appear different from your nature, to please others? To make yourself accepted?

Or be perfectly yourself, and wait for the developments that are brewing?

New beginning

“You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy”, we read in the Book of Leviticus (19:1). With these words and with the consequent precepts the Lord invited the People whom he had chosen to be faithful to the Covenant with him, to walk on his path; and he founded social legislation on the commandment “you shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Lev 19:18).

Then if we listen to Jesus in whom God took a mortal body to make himself close to every human being and reveal his infinite love for us, we find that same call, that same audacious objective. Indeed, the Lord says: “You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48).

But who could become perfect? Our perfection is living humbly as children of God, doing his will in practice. St Cyprian wrote: “that the godly discipline might respond to God, the Father, that in the honour and praise of living, God may be glorified in man (De zelo et livore [On jealousy and envy], 15: CCL 3a, 83).

How can we imitate Jesus? He said: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in Heaven” (Mt 5:44-45). Anyone who welcomes the Lord into his life and loves him with all his heart is capable of a new beginning. He succeeds in doing God’s will: to bring about a new form of existence enlivened by love and destined for eternity.

The Apostle Paul added: “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” (I Cor 3:16). If we are truly aware of this reality and our life is profoundly shaped by it, then our witness becomes clear, eloquent and effective. A medieval author wrote: “When the whole of man’s being is, so to speak, mingled with God’s love, the splendour of his soul is also reflected in his external aspect” (John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, XXX: PG 88, 1157 B), in the totality of life.

“Love is an excellent thing”, we read in the book the Imitation of Christ. “It makes every difficulty easy, and bears all wrongs with equanimity…. Love tends upward; it will not be held down by anything low… love is born of God and cannot rest except in God” (III, V, 3).

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 20 February 2011]

Forgiving and Giving. Are the words of Jesus realistic?

I ask myself: are Jesus’ words realistic? Is it really possible to love like God loves and to be merciful like He is?

If we look at the history of salvation, we see that the whole of God’s revelation is an unceasing and untiring love for mankind: God is like a father or mother who loves with an unfathomable love and pours it out abundantly on every creature. Jesus’ death on the Cross is the culmination of the love story between God and man. A love so great that God alone can understand it. It is clear that, compared to this immeasurable love, our love will always be lacking. But when Jesus calls us to be merciful like the Father, he does not mean in quantity! He asks his disciples to become signs, channels, witnesses of his mercy.

The Church can be nothing other than a sacrament of God’s mercy in the world, at every time and for all of mankind. Every Christian, therefore, is called to be a witness of mercy, and this happens along the path of holiness. Let us think of the many saints who became merciful because they allowed their hearts to be filled with divine mercy. They embodied the Lord’s love, pouring it into the multiple needs of a suffering humanity. Within the flourishing of many forms of charity you can see the reflection of Christ’s merciful face.

We ask ourselves: What does it mean for disciples to be merciful? Jesus explains this with two verbs: “forgive” (Lk 6:37) and “give” (v. 38).

Mercy is expressed, first of all, in forgiveness: “Judge not, and you will not be judged; condemn not, and you will not be condemned; forgive, and you will be forgiven” (v. 37). Jesus does not intend to undermine the course of human justice, he does, however, remind his disciples that in order to have fraternal relationships they must suspend judgment and condemnation. Forgiveness, in fact, is the pillar that holds up the life of the Christian community, because it shows the gratuitousness with which God has loved us first.

The Christian must forgive! Why? Because he has been forgiven. All of us who are here today, in the Square, we have been forgiven. There is not one of us who, in our own life, has had no need of God’s forgiveness. And because we have been forgiven, we must forgive. We recite this every day in the Our Father: “Forgive us our sins; forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us”. That is, to forgive offenses, to forgive many things, because we have been forgiven of many offenses, of many sins. In this way it is easy to forgive: if God has forgiven me, why do I not forgive others? Am I greater than God? This pillar of forgiveness shows us the gratuitousness of the love of God, who loved us first. Judging and condemning a brother who sins is wrong. Not because we do not want to recognize sin, but because condemning the sinner breaks the bond of fraternity with him and spurns the mercy of God, who does not want to renounce any of his children. We do not have the power to condemn our erring brother, we are not above him: rather, we have a duty to recover the dignity of a child of the Father and to accompany him on his journey of conversion.

Jesus also indicates a second pillar to us who are his Church: “to give”. Forgiveness is the first pillar; giving is the second pillar. “Give, and it will be given to you.... For the measure you give will be the measure you get back” (v. 38). God gives far beyond our merits, but He will be even more generous with those who have been generous on earth. Jesus does not say what will happen to those who do not give, but the image of the “measure” is a warning: with the measure that we give, it is we who determine how we will be judged, how we will be loved. If we look closely, there is a coherent logic: the extent to which you receive from God, you give to your brother, and the extent to which you give to your brother, you will receive from God!

Merciful love is therefore the only way forward. We all have a great need to be a bit more merciful, to not speak ill of others, to not judge, to not “sting” others with criticism, with envy and jealousy. We must forgive, be merciful, and live our lives with love.

This love enables Jesus’ disciples to never lose the identity they received from Him, and to recognize themselves as children of the same Father. In the love that they practice in life we see reflected that Mercy that will never end (cf. 1 Cor 13:1-12). Do not forget this: mercy is a gift; forgiveness and giving. In this way, the heart expands, it grows with love. While selfishness and anger make the heart small, they make it harden like a stone. Which do you prefer? A heart of stone or a heart full of love? If you prefer a heart full of love, be merciful!

[Pope Francis, General Audience 21 September 2016]

1st Sunday in Lent

First Lent Sunday [22 February 2026]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. I apologise if I dwell too long today on the presentation of the texts, but it is central to Christian life to understand in depth the drama of Genesis (first reading), which St Paul takes up in the second reading, bringing it to full understanding. Similarly, the responsorial psalm can be understood starting from the drama recounted in Genesis chapter 3, and likewise the Gospel shows us how to react in order to live in the kingdom of God already on this earth. In my opinion, it is a vision of life that must be clearly focused in order to understand the drama of the practical and often unconscious rejection of God that is consummated in the world in the face of the crucial question: why is there evil in the world? Why does God not destroy it?

Have a good Lent.

*First Reading from the Book of Genesis (2:7-9; 3:1-7a)

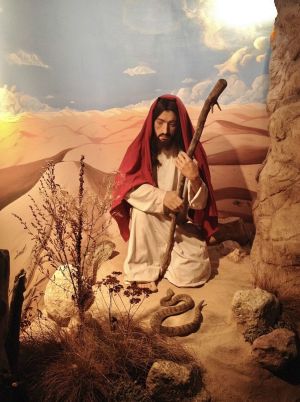

In the first chapters of Genesis, two different figures of man appear: the first who lives happily in complete harmony with God and with woman. and creation (chap. 2), and then the man who claims his autonomy by taking for himself the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (chap. 3). Jesus sums up in himself 'all our weaknesses' (Heb 4:15), and, put to the test, he will be the sign of the new humanity: 'the last Adam became a life-giving spirit' (1 Cor 15:45). Before tackling this text, we must remember that its author never claimed to be a historian. The Bible was written neither by scientists nor by historians, but by believers for believers. The theologian who wrote these lines, probably at the time of Solomon in the 10th century BC, seeks to answer the questions that everyone asks: why evil? Why death? Why misunderstandings between couples? Why is life so difficult? Why is work so tiring? Why is nature sometimes hostile? To answer these questions, he draws on a certainty shared by his entire people: the goodness of God. God freed us from Egypt; God wants us to be free and happy. Since the famous exodus from Egypt, led by Moses, and the crossing of the desert, during which God's presence and support were experienced at every new difficulty, there can be no doubt about this. The story we have just read is therefore based on this certainty of God's benevolence and seeks to answer all our questions about evil in the world. With a good and benevolent God, how is it possible that evil exists? Our author has invented a parable to enlighten us: a garden of delights (this is the meaning of the word 'Eden') and humanity represented by a couple charged with cultivating and caring for the garden. The garden is full of trees, each more attractive than the next. The one in the middle is called the 'tree of life'; its fruit can be eaten like all the others. But somewhere in the garden – the text does not specify where – there is another tree, whose fruit is forbidden. It is called the 'tree of the knowledge of what makes one happy or unhappy'. Faced with this prohibition, the couple can have two attitudes: either to trust, knowing that God is only benevolence, and rejoice in having access to the tree of life; if God forbids us the other tree, it is because it is not good for us. Or they can suspect God of having evil intentions, imagining that he wants to prevent us from accessing knowledge. This is the serpent's argument: he addresses the woman and feigns understanding: 'So, did God really say, "You must not eat from any tree in the garden"?' (3:1). The woman replies: "We may eat the fruit of the trees in the garden, but God has said, 'You must not eat the fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden, nor touch it, or you will die'" (3:2-4) . Have you noticed the shift: simply because she has listened to the voice of suspicion, she now speaks only of that tree and says 'the tree in the middle of the garden'; now, in good faith, she no longer sees the tree of life in the centre of the garden, but the tree 'of the knowledge of what makes one happy or unhappy'. Her gaze is already altered, simply because she has allowed the serpent to speak to her; then the serpent can continue its slow work of demolition: "No, you will not die at all! Indeed, God knows that on the day you eat of it, your eyes will be opened and you will be like God, knowing good and evil" (3:5). Once again, the woman listens too well to these beautiful words, and the text suggests that her gaze is increasingly distorted: 'The woman saw that the tree was good for food, pleasing to the eye, and desirable for gaining wisdom' (3:6). The serpent has won: the woman takes the fruit, eats it, gives it to her husband, and he eats it too. And so the story ends: "Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked" (v. 7). The serpent had spoken well: "your eyes will be opened" (3:5); the woman's mistake was to believe that he was speaking in her interest and revealing God's evil intentions. It was nothing but a lie: her gaze changed, it is true, but it became distorted. It is no coincidence that the suspicion cast on God is represented by the features of a serpent: Israel, in the desert, had experienced poisonous snakes. Our theologian at Solomon's court recalls this painful experience and says: there is a poison more serious than that of the most poisonous snakes; the suspicion cast on God is a deadly poison, it poisons our lives. The idea of our anonymous theologian is that all our misfortunes come from this suspicion that corrodes humanity. To say that the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is reserved for God is to say that only God knows what makes us happy or unhappy; which, after all, is logical if he is the one who created us. Wanting to eat the fruit of this forbidden tree at all costs means claiming to determine for ourselves what is good for us: the warning 'You must not eat it and you must not touch it, otherwise you will die' clearly indicated that this was the wrong path to take.

But wait! The story goes even further: during the journey through the desert, God gave the Law (the Torah) which from then on had to be observed, what we call the commandments. We know that the daily practice of this Law is the condition for the survival and harmonious growth of this people; if we truly knew that God only wants our life, our happiness, our freedom, we would trust and obey the Law with a good heart. It is truly the "tree of life" made available to us by God.

I said at the beginning that this is a parable, but it is a parable whose lesson applies to each of us; since the world began, it has always been the same story. St Paul (whom we read this Sunday in the second reading) continues his meditation and says: only Christ trusted the Father in everything; he shows us the way of Life.

Note: In the Hebrew text, the serpent's question is deliberately ambiguous: 'Did God really say, "You shall not eat of any tree in the garden"? 'הֲכִי־אָמַר אֱלֹהִים לֹא תֹאכְלוּ מִכֹּל עֵץ הַגָּן? " Ha-ki amar Elohim lo tochlu mikol etz ha-gan? Put this way, the question can be understood in a restrictive sense: "Did God really say, 'You shall not eat of any tree in the garden'?" interpreting "all trees" as a total negation. Or in a general and colloquial sense: "Did God really say, 'You shall not eat of any tree in the garden'?" interpreting "all" in an absolute sense, or as all trees except one, the tree of life or the other of the knowledge of good and evil. The serpent uses this ambiguity to sow doubt and suspicion, insinuating that God might be lying or withholding something good. In the oldest Hebrew manuscripts, there are no punctuation marks as we know them today, so the play on words and the double meaning were intentionally stronger. Exegetes note that the serpent does not make a clear statement but forms a subtle question that shifts the focus to doubt: "Perhaps God is deceiving you?" This account in Genesis has many resonances in the meditation of the people of Israel. One of the reflections suggested by the text concerns the tree of life: planted in the middle of the garden of Eden, it was accessible to man and its fruit was permitted. One might think that its fruit allowed man to remain alive, to that spiritual life that God had breathed into him: "The Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground, breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being" (Gen 2:7). The rabbis then made the connection with the Law given by God on Sinai. In fact, it is accepted by believers as a gift from God, a support for daily life: 'My son, do not forget my teaching, but keep my commands in your heart, for they will prolong your life and bring you peace' (Pr 3:1-2). .

NB For further clarification, I would add this: There is the first prohibition: the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in Genesis 2:16-17, God sets only one limit on man: "Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil thou shalt not eat." The tree of life is not forbidden at this point. The prohibition concerns only the tree of the knowledge of good and evil because God is the one who decides what is good and what is evil, and man is called to trust, not to replace God. Eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge means saying, 'I do not trust God; I decide what is good and what is evil'. After sin, there is a second prohibition (the tree of life) because the situation changes radically. In Genesis 3:22-24, we read: 'Now, lest he reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life and eat, and live forever'. Only after sin does God prevent access to the tree of life. Why? Because man, separated from God by sin, cannot live forever like this. Living eternally with the consequences of sin would be a condemnation, not a gift. God therefore protects man from a distorted immortality. In other words, God does not take life away as punishment, but to prevent evil from becoming eternal.

*Responsorial Psalm (50/51)

"Have mercy on me, O God, in your love; according to your great mercy, blot out my sin. Wash me completely from my guilt, purify me from my offence." The people of Israel are gathered for a great penitential celebration in the Temple of Jerusalem. They recognise themselves as sinners, but they also know God's inexhaustible mercy. After all, if they are gathered to ask for forgiveness, it is because they already know in advance that forgiveness has been granted. This, let us remember, was King David's great discovery: David took Bathsheba, with whom he had fallen in love, and had her husband Uriah killed, because a few days later, Bathsheba was expecting a child by him. When the prophet Nathan went to David, he did not first seek a word of repentance from him; instead, he began by reminding him of all God's gifts and announcing his forgiveness, even before David had had time to make the slightest confession (2 Sam 12). In essence, he said to him, 'Look at all that God has given you... well, know that he is ready to give you anything else you want!'. And a thousand times throughout its history, Israel has been able to verify that God is truly 'the merciful and compassionate Lord, slow to anger and rich in love and faithfulness', according to the revelation he granted to Moses in the desert (Ex 34:6). The prophets also transmitted this message, and the few verses of the psalm we have just heard are full of these discoveries of Isaiah and Ezekiel. Isaiah, for example: "It is I, I who blot out your transgressions for my own sake, and I will not remember your sins" (Is 43:25); or again: "I have blotted out your transgressions like a cloud and your sins like mist. Return to me, for I have redeemed you" (Is 44:22).

This proclamation of God's gratuitous forgiveness sometimes surprises us: it seems too good, perhaps; for some it even seems unfair: if everything is forgivable, what is the point of making an effort? Perhaps we are too quick to forget that we all, without exception, need God's mercy; so let us not complain about it! And let us not be surprised if God surprises us, for, as Isaiah says, "God's thoughts are not our thoughts". And Isaiah himself points out that it is above all in the matter of forgiveness that God surprises us most. The only condition required is to recognise ourselves as sinners. When the prodigal son (Lk 15) returns to his father, for reasons that are not very noble, Jesus puts a phrase from Psalm 50 on his lips: "Against you, against you alone, have I sinned," and this simple phrase restores the bond that the ungrateful young man had broken. Faced with this ever-renewed proclamation of God's mercy, the people of Israel — for it is they who speak here, as in all the psalms — recognise themselves as sinners: the confession is not detailed, as it never is in the penitential psalms, but the essential is said in this plea: "Have mercy on me, O God, in your love, according to your great mercy, blot out my sin... And God, who is all mercy, that is, as if drawn by misery, expects nothing more than this simple recognition of our poverty. The word "mercy" has the same root as the word "alms": literally, we are beggars before God. Two things remain to be done. First of all, simply give thanks for the forgiveness granted without ceasing; the praise that the people of Israel address to God is the recognition of the goodness with which he has filled them since the beginning of their history. This clearly shows that the most important prayer in a penitential celebration is thanksgiving for God's gifts and forgiveness: we must begin by contemplating Him, and only then, when this contemplation has revealed to us the gap between Him and us, can we recognise ourselves as sinners. The ritual of reconciliation says this clearly in its introduction: 'We confess God's love together with our sin'. And the song of gratitude will flow spontaneously from our lips: we need only allow God to open our hearts. "Lord, open my lips, and my mouth shall proclaim your praise"; some recognise here the first sentence of the Liturgy of the Hours each morning; in fact, it is taken from Psalm 50/51. This alone is a true lesson: praise and gratitude can only arise in us if God opens our hearts and our lips. St Paul puts it another way: 'God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, "Abba!", that is, "Father!"' (Gal 4:6). This irresistibly brings to mind a gesture of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark: the healing of a deaf-mute; touching his ears and tongue, Jesus said, 'Ephphatha', which means 'Be opened'. And then, spontaneously, those present applied to Jesus a phrase that the Bible reserved for God: "He makes the deaf hear and the mute speak" (cf. Is 35:5-6). Even today, in some baptismal celebrations, the celebrant repeats this gesture of Jesus on the baptised, saying: "The Lord Jesus has made the deaf hear and the mute speak; may he grant you to hear his word and proclaim your faith, to the praise and glory of God the Father". The second thing to do, and what God expects of us, is to forgive in turn, without delay or conditions... and this is a serious undertaking in our lives.

*Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Romans (5:12-19)

Adam was a figure of the one who was to come, Paul tells us; he speaks of Adam in the past tense because he refers to the book of Genesis and the story of the forbidden fruit, but for him Adam's drama is not a story of the past: this story is ours, every day; we are all Adam at times; the rabbis say, 'everyone is Adam to himself'.

And if we were to summarise the story of the Garden of Eden (which we reread in this Sunday's first reading), we could say this: by listening to the voice of the serpent rather than God's command, by allowing suspicion about God's intentions to invade their hearts, by believing that they could allow themselves everything, that they could 'know' everything - as the Bible says — man and woman placed themselves under the dominion of death. And when we say, 'everyone is Adam to himself', it means that every time we turn away from God, we allow the powers of death to invade our lives. St Paul, in his letter to the Romans, continues the same meditation and announces that humanity has taken a decisive step in Jesus Christ; we are all brothers and sisters of Adam and we are all brothers and sisters of Jesus Christ; we are brothers and sisters of Adam when we allow the poison of suspicion to infest our hearts, when we presume to make ourselves the law. We are brothers and sisters of Christ when we trust God enough to let him guide our lives. We are under the dominion of death when we behave like Adam; when we behave like Jesus, that is, like him, 'obedient' (i.e. trusting), we are already resurrected in the kingdom of life, the one John speaks of: 'He who believes in me, even if he dies, will live', a life that biological death does not interrupt. Let us return to the account in the Book of Genesis: The Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground; he breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being. This breath of God that makes man a living being – as the text says – was not given to animals: yet they are very much alive in a biological sense; we can therefore deduce that man enjoys a life different from biological life. St Paul affirms that because of Adam, death has reigned: he uses the terms 'reign' and 'reign over' several times, showing that there are two kingdoms that confront each other: the kingdom of sin when humanity acts like Adam, which brings death, judgement and condemnation. Then there is the kingdom of Christ, that is, with him, the new humanity, which is the kingdom of grace, of life, of free gift, of justification. However, no man is entirely in the kingdom of Christ, and Paul himself recognises this: 'I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want' (Rom 7:19). . Adam, that is, humanity, was created to be king, to cultivate and keep the garden, as we read in the book of Genesis, but, ill-advised by the serpent, he wants to do everything by himself, with his own strength, cutting himself off from God. Jesus Christ, on the contrary, does not 'claim' this kingship: it is given to him. As Paul writes in his letter to the Philippians: "though he was in the form of God, he did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself" (2:6, NRSV). The story of the Garden of Eden says the same thing in images: before the Fall, man and woman could eat the fruit of the tree of life; after the Fall, they no longer have access to it. Each in its own way, these two texts – that of Genesis on the one hand and that of the letter to the Romans on the other – tell us the deepest truth of our lives: with God, everything is grace, everything is a free gift; and Paul here insists on the abundance, on the profusion of grace, even speaking of the 'disproportion' of grace: It is not like the fall, the free gift... much more, God's grace has been poured out in abundance on the multitude, this grace given in one man, Jesus Christ. Everything is a gift, and this is not surprising since, as St John says, God is Love. It is not because Christ behaved well that he received a reward, and Adam received punishment because of his misconduct. Paul's discourse is deeper: Christ lives in total trust that everything will be given to him in God... and everything is given to him in the Resurrection. Adam, that is, each one of us, often wants to take possession of what can only be received as a gift, and for this reason finds himself 'naked', that is, deprived of everything. We could say that by birth we are citizens of the kingdom of Adam; through baptism we have asked to be naturalised in the kingdom of Christ. Obedience and disobedience in Paul's sense could thus be replaced: 'obedience' with trust and 'disobedience' with mistrust; as Kierkegaard says: "The opposite of sin is not virtue; the opposite of sin is faith." If we reread the story of Genesis, we can see that the author intentionally did not give proper names to the man and woman; he spoke of Adam (derived from adamah, meaning earth, dust), which means 'human being taken from the earth', while Eve (derived from Chavah, meaning life) is the one who gives life. By not giving them names, he wanted us to understand that the drama of Adam and Eve is not the story of particular individuals, but the story of every human being, and has always been so.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (4:1-11)

Every year, Lent begins with the story of Jesus' temptations in the desert: we must believe that this is a truly fundamental text! This year we read it according to St Matthew. After recounting the baptism of Jesus, Matthew immediately continues: "Jesus was led by the Spirit into the desert to be tempted by the devil" . The evangelist thus invites us to make a connection between Jesus' baptism and the temptations that immediately follow. Matthew had said a few verses earlier: Jesus "will save his people from their sins", which is precisely the meaning of the name Jesus. John the Baptist baptises Jesus in the Jordan even though he did not agree and had said: " I need to be baptised by you, and yet you come to me!" (Mt 3:14)... And it came to pass that when Jesus came up out of the water after his baptism, the heavens opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and coming upon him. And a voice came from heaven, saying, "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased."

This phrase alone publicly announces that Jesus is truly the Messiah: because the expression 'Son of God' was synonymous with King-Messiah, and the phrase 'the beloved, in whom I am well pleased' (3:17) refers to one of the songs of the Servant in Isaiah. In a few words, Matthew reminds us of the whole mystery of the person of Jesus; and it is he, precisely, who is the Messiah, the Saviour, the Servant who will confront the Tempter. Like his people a few centuries earlier, he is led into the desert; like his people, he knows hunger; like his people, he must discover what God's will is for his children; like his people, he must choose before whom to bow down. "If you are the Son of God," repeats the Tempter, thus revealing the real problem; and Jesus is confronted with it, not only three times, but throughout his earthly life. What does it mean, in concrete terms, to be the Messiah? The question takes various forms: solving people's problems with miracles, such as turning stones into bread? Provoking God to test his promises? ... By throwing himself from the temple, for example, because Psalm 91 promised that God would rescue his Messiah... Possessing the world, dominating, reigning at any cost, even worshipping any idol? Even ceasing to be the Son? It should be noted that in the third temptation, the Tempter no longer repeats "If you are the Son of God".

The culmination of these temptations is that they target God's promises: they promise nothing more than what God himself promised to his Messiah. And the two interlocutors, the Tempter and Jesus, know this well. But here's the thing... God's promises are in the order of love; they can only be received as gifts; love cannot be demanded, it cannot be seized, it is received on bended knee, with gratitude. Ultimately, the same thing happens as in the Garden of Genesis: Adam knows, and rightly so, that he was created to be king, to be free, to be master of creation; but instead of accepting gifts as gifts, with gratitude and appreciation, he demands, he claims, he places himself on a par with God... He leaves the order of love and can no longer receive the love offered... he finds himself poor and naked. Jesus makes the opposite choice: 'Get behind me, Satan!' as he once said to Peter, adding, 'Your thoughts are not those of God, but those of men' (Mt 16:23). Furthermore, several times in this text, Matthew calls the Tempter "devil," which in Greek means "the one who divides." Satan is for each of us, as he is for Jesus himself, the one who tends to separate us from God, to see things in Adam's way and not in God's way. On closer inspection, it all lies in the gaze: Adam's is distorted; to keep his gaze clear, Jesus scrutinises the Word of God: the three responses to the Tempter are quotations from the book of Deuteronomy (chapter 8), in a passage that is precisely a meditation on the temptations of the people of Israel in the desert. Then, Matthew points out, the devil (the divider) leaves him; he has not succeeded in dividing, in turning away the Son's heart. This recalls St John's phrase in the Prologue (Jn 1:1): 'In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God (pros ton Theon, which means turned towards God), and the Word was God'. . The devil has not succeeded in turning the Son's heart away, and so he is then completely available to receive God's gifts: "Behold, angels came and ministered to him."

NB At the request of some, I would also like to present the homily I am preparing for this first Sunday of Lent.

Homily – First Sunday of Lent

Every year, Lent begins with the story of Jesus' temptations in the desert: we must believe that this is a truly fundamental text! This year we read it according to St Matthew. After recounting the baptism of Jesus, Matthew immediately continues: "Jesus was led by the Spirit into the desert to be tempted by the devil." The evangelist thus invites us to make a connection between the baptism of Jesus and the temptations that immediately follow. When Jesus came up out of the water, the heavens opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and coming upon him. And a voice came from heaven, saying, 'This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased'. Jesus is the 'Son of God', the Messiah, the Saviour, the servant of God who will face the Tempter. Satan will say just that: "If you are the Son of God," thus revealing the real problem, which is the attempt to separate Jesus' divine identity from his way of living it, or better yet, to push Jesus to use his divine power without the trust of a son and his humanity without obedience. To understand this better, we must return to the first reading from the book of Genesis, where the tempting serpent promises Eve: "You will be like God" (Gen 3:5). The temptation is not only about a fruit that should not be eaten, but about autonomy from God, the desire to decide for oneself what is good and evil, without trusting the Father. Adam and Eve allowed themselves to be persuaded and found themselves naked. They lost everything!

In the desert, the devil now tempts Jesus, the new Adam, a true man like us except for sin, and launches three provocations: 1. "Say that these stones become bread." The temptation to live without depending on God, to seek immediate satisfaction. There is a hunger that goes beyond bread and that only God can satisfy. But this means trusting God, and Jesus responds: 'It is written: Man shall not live by bread alone' (Mt 4:4). 2nd temptation. The devil raises the stakes: "Throw yourself down" from the temple and the angels will catch you. Here is the temptation to manipulate God, to ask for spectacular signs to confirm one's faith. This is a very subtle temptation today, but one that is very common when we believe in making the liturgy, evangelisation and ecclesial events spectacular. Jesus teaches us to spread the Gospel like yeast in dough and a small seed in the ground: everything happens in silence because we must not believe that we are protagonists but lives always hidden in God, even when we act publicly. It is not our work to convert the world. Let us listen to Jesus who replies: "It is written: You shall not tempt the Lord your God" (Mt 4:7). . 3. In the third temptation, it should be noted that the Tempter no longer repeats 'If you are the Son of God', because Satan believes himself to be the master of the world and so he can say to him, 'I will give you everything if you bow down to me'. It is the temptation of power and compromise, of bending one's life to immediate advantages. It is very dangerous because it often involves the idea that we can accept anything in order to evangelise, but we are not the masters! Jesus replies: "It is written: You shall worship the Lord your God and him alone shall you serve" (Mt 4:10).

Let us note something decisive: Jesus does not respond with his own intelligence or strength, but always by referring to the Word of God, which is the only true light that can guide man's journey through the desert of life, a journey that is often dark and full of pitfalls. This is because the Word of God is the light of truth that never goes out. St John Chrysostom reminds us: "In Scripture we find not only words, but the strength we need to overcome evil; it is the nourishment of the soul and the light that guides those who walk in darkness" (Homilies on Matthew, 4th century). Even when the world rejects God, even when the right choices seem uncomfortable or losing, Scripture remains the sure guide. How can we apply this to our lives? Today, being a Christian is often difficult: faith can be mocked or ignored, the Gospel seems useless, Christ is fought against and sometimes tolerated, but not welcomed. Lent invites us to make a daily choice: who guides our lives? Do we want to do everything on our own, like Eve and Adam in Eden, choosing what seems most convenient? Or do we entrust ourselves to God, allowing his Word to enlighten our decisions and give meaning even to our difficulties? Following Christ means choosing fidelity, even when the world goes against it. It means living our lives as Christians without compromise, basing ourselves not on personal strength, but on the living Word of God. We are always sustained by a certain and concrete hope: the Gospel ends with a silent promise: 'Then the devil left him' (Mt 4:11). Those who entrust themselves to God are not left alone in their trials. Temptation may seem powerful, but those who walk in the light of the Word are never defeated.

+Giovanni D’Ercole

First debt: a greater Justice

(Mt 5:20-26)

«I tell you in fact that unless your righteousness will abound more [that] of the scribes and pharisees, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven»

In the churches of Galilee and Syria there were different and conflicting opinions about the Law of Moses: for some an absolute to be fulfilled even in detail, for others now a meaningless frill (v.22).

The disputants went so far as to insult, to ridicule the opposing party.

But as the Tao Tê Ching (xxx) says: «Where the militias are stationed, thorns and brambles are born». Master Wang Pi comments: «He who promotes himself causes unrest, because he strives to affirm his merits».

Mt helps all community sisters and brothers to understand the content of the ancient Scriptures and grasp the attitude of ‘continuity and cut’ given by the Lord: «You have heard that [...] Now I say to you» (vv.21-22).

‘Arrow’ of the ancient codes was shot in the right direction, but only understanding its range in the spirit of concordance sustains trajectory to the point of providing the energy needed to hit the “target”.

Ideal of ancient religiosity was to present oneself pure before God, and in this sense the Scribes official theologians of the Sanhedrin emphasised the value of the rules that they believed were nestled in the First Testament ‘prison of the letter’.

Sadducees - the priestly class - focused on the sacrificial observances of the Torah alone.

Pharisees, leaders of popular religiosity, emphasised the respect for all traditional customs.

Teaching of professionals of the sacred produced in the people a sense of legalistic oppression that obscured the spirit of the Word of God and of Tradition itself.

Jesus brings out the goal: the greater Justice of Love.

The splendor, beauty and richness of the Glory of the living God is not produced in observing, but in the ability to manifest Him Present.

The right position before Father becomes - in Jesus' proposal - the right position before one's own history and that of one’s neighbor.

First «debt» is therefore a ‘global understanding’: here the Eternal is revealed.

Justice is not the product of the accumulation of righteous deeds, in view of merit: this would manifest narrowness, detachment and arrogance (a type of man of unquestioning thought).

The new Justice chases complicity with evil up to the secret roots of the heart and ideas. But not to accentuate the sense of guilt, nor to make us pursues external dreams.

Observance that does not abide in friendship, in tolerance even of oneself, in Christ who orients, would arise from an ambiguous relationship with the norm and doctrines.

We can overlook the childish need for approval.

The Life of God transpires in a world not of sterilised or pure and phlegmatic one-sided people, but in a conviviality of differences that resembles Him.

To internalize and live the message:

Where do you find the emotional nourishment you need?

What do you think of exclusive groups and their idea of the ultimate court?

[Friday 1st wk. in Lent, February 27, 2026]

Discord also with creation

If man is not reconciled with God, he is also in conflict with creation. He is not reconciled with himself, he would like to be something other than what he is and consequently he is not reconciled with his neighbour either. Part of reconciliation is also the ability to acknowledge guilt and to ask forgiveness from God and from others. Lastly, part of the process of reconciliation is also the readiness to do penance, the willingness to suffer deeply for one's sin and to allow oneself to be transformed. Part of this is the gratuitousness of which the Encyclical Caritas in Veritate speaks repeatedly: the readiness to do more than what is necessary, not to tally costs, but to go beyond merely legal requirements. Part of this is the generosity which God himself has shown us. We think of Jesus' words: "If you are offering your gift at the altar, and there remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother, and then come and offer your gift" (Mt 5: 23ff.). God, knowing that we were unreconciled and seeing that we have something against him, rose up and came to meet us, even though he alone was in the right. He came to meet us even to the Cross, in order to reconcile us. This is what it means to give freely: a willingness to take the first step; to be the first to reach out to the other, to offer reconciliation, to accept the suffering entailed in giving up being in the right. To persevere in the desire for reconciliation: God gave us an example, and this is the way for us to become like him; it is an attitude constantly needed in our world. Today we must learn once more how to acknowledge guilt, we must shake off the illusion of being innocent. We must learn how to do penance, to let ourselves be transformed; to reach out to the other and to let God give us the courage and strength for this renewal.

[Pope Benedict, Address to the Roman Curia 21 December 2009]

Difference that restores

1. In the Gospels we find another fact that attests to Jesus' consciousness of possessing divine authority, and the persuasion that the evangelists and the early Christian community had of this authority. In fact, the Synoptics agree in saying that Jesus' listeners "were amazed at his teaching, because he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes" (Mk 1:22; Mt 7:29; Lk 4:32). This is valuable information that Mark gives us from the very beginning of his Gospel. It attests to the fact that the people had immediately grasped the difference between Christ's teaching and that of the Israelite scribes, and not only in the manner, but in the very substance: the scribes based their teaching on the text of the Mosaic Law, of which they were the interpreters and commentators; Jesus did not at all follow the method of a "teacher" or a "commentator" of the ancient Law, but behaved like a legislator and, ultimately, like one who had authority over the Law. Note: the listeners were well aware that this was the divine Law, given by Moses by virtue of power that God himself had granted him as his representative and mediator with the people of Israel.

The evangelists and the early Christian community who reflected on that observation of the listeners about Jesus' teaching, realised even better its full significance, because they could compare it with the whole of Christ's subsequent ministry. For the Synoptics and their readers, it was therefore logical to move from the affirmation of a power over the Mosaic Law and the entire Old Testament to that of the presence of a divine authority in Christ. And not only as in an Envoy or Legate of God as it had been in the case of Moses: Christ, by attributing to himself the power to authoritatively complete and interpret or even give in a new way the Law of God, showed his consciousness of being "equal to God" (cf. Phil 2:6).

2. That Christ's power over the Law involves divine authority is shown by the fact that he does not create another Law by abolishing the old one: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have not come to abolish but to fulfil" (Mt 5:17). It is clear that God could not "abolish" the Law that he himself gave. He can instead - as Jesus Christ does - clarify its full meaning, make its proper sense understood, correct the false interpretations and arbitrary applications, to which the people and their own teachers and leaders, yielding to the weaknesses and limitations of the human condition, have bent it.

This is why Jesus announces, proclaims and demands a "righteousness" superior to that of the scribes and Pharisees (cf. Mt 5:20), the "righteousness" that God Himself has proposed and demands with the faithful observance of the Law in order to the "kingdom of heaven". The Son of Man thus acts as a God who re-establishes what God has willed and placed once and for all.

3. For of the Law of God he first of all proclaims: "Verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass away, not one iota or one sign of the law shall pass away, and all things shall be fulfilled" (Matt 5:18). It is a drastic statement, with which Jesus wants to affirm both the substantial immutability of the Mosaic Law and the messianic fulfilment it receives in his word. It is about a "fullness" of the Old Law, which he, teaching "as one who has authority" over the Law, shows to be manifested above all in love of God and neighbour. "On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets" (Mt 22:40). It is a "fulfilment" corresponding to the "spirit" of the Law, which already transpires from the "letter" of the Old Testament, which Jesus grasps, synthesises, and proposes with the authority of one who is Lord also of the Law. The precepts of love, and also of the faith that generates hope in the messianic work, which he adds to the ancient Law, making its content explicit and developing its hidden virtues, are also a fulfilment.

His life is a model of this fulfilment, so that Jesus can say to his disciples not only and not so much: Follow my Law, but: Follow me, imitate me, walk in the light that comes from me.

4. The Sermon on the Mount, as recorded by Matthew, is the place in the New Testament where one sees Jesus clearly affirmed and decisively exercised the power over the Law that Israel received from God as the cornerstone of the covenant. It is there that, after having declared the perennial value of the Law and the duty to observe it (Mt 5:18-19), Jesus goes on to affirm the need for a "justice" superior to "that of the scribes and Pharisees", that is, an observance of the Law animated by the new evangelical spirit of charity and sincerity.

The concrete examples are well known. The first consists in the victory over wrath, resentment, and malice that easily lurk in the human heart, even when an outward observance of the Mosaic precepts can be exhibited, including the precept not to kill: "You have heard that it was said to the ancients: 'You shall not kill; whoever kills shall be brought into judgment. But I say to you, whoever is angry with his brother shall be brought into judgment" (Mt 5:21-22). The same thing applies to anyone who offends another with insulting words, with jokes and mockery. It is the condemnation of every yielding to the instinct of aversion, which potentially is already an act of injury and even of killing, at least spiritually, because it violates the economy of love in human relationships and hurts others, and to this condemnation Jesus intends to counterpose the Law of charity that purifies and reorders man down to the innermost feelings and movements of his spirit. Jesus makes fidelity to this Law an indispensable condition of religious practice itself: "If therefore you present your offering at the altar and there you remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar, and go first to be reconciled with your brother and then return to offer your gift" (Mt 5:23-24). Since it is a law of love, it is even irrelevant who it is that has something against the other in his heart: the love preached by Jesus equals and unifies everyone in wanting what is good, in establishing or restoring harmony in relations with one's neighbour, even in cases of disputes and legal proceedings (cf. Mt 5:25).

5. Another example of perfecting the Law is that concerning the sixth commandment of the Decalogue, in which Moses forbade adultery. In hyperbolic and even paradoxical language, designed to draw the attention and shake the mood of his listeners, Jesus announces. "You have heard that it was said, Do not commit adultery, but I say to you . . ." (Mt 5:27); and he also condemns impure looks and desires, while recommending the flight from opportunities, the courage of mortification, the subordination of all acts and behaviour to the demands of the salvation of the soul and of the whole man (cf. Mt 5:29-30).

This case is related in a certain way to another one that Jesus immediately addresses: "It was also said: Whoever repudiates his wife, let him give her the act of repudiation; but I say to you . . ." and declares forfeited the concession made by the old Law to the people of Israel "because of the hardness of their hearts" (cf. Mt 19:8), prohibiting also this form of violation of the law of love in harmony with the re-establishment of the indissolubility of marriage (cf. Mt 19:9).

6. With the same procedure, Jesus contrasts the ancient prohibition of perjury with that of not swearing at all (Mt 5, 33-38), and the reason that emerges quite clearly is still founded in love: one must not be incredulous or distrustful of one's neighbour, when he is habitually frank and loyal, and rather one must on the one hand and on the other follow this fundamental law of speech and action: "Let your language be yes, if it is yes; no, if it is no. The more is from the evil one" (Mt 5:37).

7. And again: "You have heard that it was said, 'An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth; but I say to you, do not oppose the evil one...'" (Mt 5:38-39), and in metaphorical language Jesus teaches to turn the other cheek, to surrender not only one's tunic but also one's cloak, not to respond violently to the anguish of others, and above all: "Give to those who ask you and to those who seek a loan from you do not turn your back" (Mt 5:42). Radical exclusion of the law of retribution in the personal life of the disciple of Jesus, whatever the duty of society to defend its members from wrongdoers and to punish those guilty of violating the rights of citizens and the state itself.