don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Fifth Beatitude

Today we will consider the fifth Beatitude which says: “Blessed are the merciful for they shall obtain mercy” (Mt 5:7). There is a peculiar aspect to this beatitude. It is the only one in which the cause and the fruit of happiness coincide: mercy. Those who show mercy will find mercy, they will be “shown mercy”.

This theme of reciprocity of forgiveness is not found only in this Beatitude, but is recurrent throughout the Gospel. How could it be otherwise? Mercy is the very heart of God! Jesus says: “Judge not, and you will not be judged; condemn not, and you will not be condemned; forgive and you will be forgiven” (Lk 6:37). It is always the same reciprocity. And the Letter of James states that “mercy triumphs over judgment” (Jam 2:13).

But it is above all in the “Lord's Prayer” that we pray: “forgive us our debts as we also have forgiven our debtors” (Mt 6:12); and this question is taken up again at the end: “For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you; but if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses (Mt 6:14-15; cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2838).

There are two things that cannot be separated: forgiveness granted and forgiveness received. However, many people struggle; they cannot forgive. Often the harm received is so great that being able to forgive feels like climbing a very high mountain: an enormous effort; and one thinks: it cannot be done, this cannot be done. This fact of the reciprocity of mercy shows that we have to overturn the perspective. We cannot do this alone. We need God’s grace, we must ask for it. Indeed if the fifth Beatitude promises mercy, and in the “Lord's Prayer” we ask for the forgiveness of debts, it means that we are essentially debtors and we need to find mercy!

We are all debtors. All of us. To God who is so generous and to our brothers and sisters. Everyone knows that he/she is not the father or mother that he or she should be, the bride or groom, the brother or sister. We are all “in deficit” in life. And we need mercy. We know that we too have done wrong. There is always something lacking in the good that we should have done.

However, our very poverty becomes our strength to forgive! We are debtors and if, as we heard at the start, we shall be measured with the same measure with which we measure others (cf. Lk 6:38), then it would suit us to widen our measure and to forgive debts; to forgive. Each person should remember that they need to forgive, they are in need of forgiveness and they need patience. This is the secret to mercy: by forgiving one is forgiven. Thus God precedes us and he forgives us first (cf. Rom 5:8). In receiving his forgiveness, we too are capable of forgiving. One’s own misery and lack of justice therefore, become opportunities to open oneself up to the Kingdom of Heaven, to a greater measure, the measure of God who is mercy.

Where does our mercy come from? Jesus told us: “Be merciful, even as your Father is merciful” (Lk 6:36). The more one welcomes the Father’s love, the more we can love (cf. CCC 2842). Mercy is not a dimension among others but rather the centre of Christian life. There is no Christianity without mercy [Cf. Saint John Paul II, Encyclical Dives in Misericordia (30 November 1980); Misericordae Vultus Bull (11 April 2015); Apostolic Letter Misericordia et misera (20 November 2016)]. If all our Christianity does not lead us to mercy, then we have taken the wrong path because mercy is the only true destination of all spiritual journeys. It is one of the most beautiful fruits of mercy (cf. CCC 1829).

I remember that this theme was chosen for the first Angelus that I had to recite as Pope: mercy. And this has remained very much impressed on me, as a message that I would always have to offer as Pope, a message for everyday: mercy. I remember that on that day I even had an attitude that was somewhat “brazen”, as if I were advertising a book about mercy that had just been published by Cardinal Kasper. And on that day I felt very strongly that this is the message that I must offer as Bishop of Rome: mercy, mercy, please, forgiveness.

God’s mercy is our liberation and our happiness. We live of mercy and we cannot afford to be without mercy. It is the air that we breathe. We are too poor to set any conditions. We need to forgive because we need to be forgiven. Thank you!

[1] Cf. St John Paul II, Enc. Dives in misericordia (30 November 1980); Bull Misericordae Vultus (11 April 2015); Ap. Lett. Misericordia et misera (20 November 2016).

(Pope Francis, General Audience 18 March 2020)

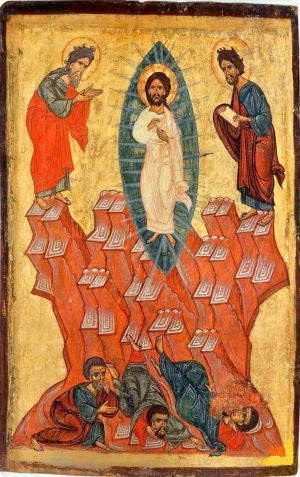

Against the tide Transfiguration

Faith and Metamorphosis

(Mk 9:2-13)

In biblical language, the experience of «the Mount» is an icon of the Encounter between God and man. Yes, for us it’s like “losing our minds”, but in a very practical way - not at all visionary.

The Master imposes it on the three eminent figures of the first communities, not because he considers them the chosen ones, but the exact opposite: he realizes that it’s his captains who need verification.

The synoptic Gospels do not speak of Transfiguration any, but of «Metamorphosis» [Greek text of Mk 9:2 and Mt 17:2]: a passing under a different ‘form’.

In particular, Lk 9:29 emphasizes that «the appearance of his face became ‘other’». Not because of a paroxysmal state.

It sounds crazy, but the hieratic magnificence of the Eternal One is revealed against the tide: in the image of the humble servant.

The experience of divine Glory is unsustainable for the eminent disciples - not in reference to physical flashes of light.

As in Oriental icons, they find themselves face to earth [Mt 17:6 - in ancient Eastern culture it meant precisely: "defeated" in their aspirations] and frightened. Fearful of being they too called to the gift of self (Mk 9:6; Mt 17:6; Lk 9:34-36).

The vertigo of the experience of God was not what they cultivated and wanted.

The dazzling light to which the passage refers (Mk 9:3; Mt 17:2.5; Lk 9:29) is that of a Revelation that opens our eyes to the "impossible" identity of the Son.

He was popularly expected as resembling David, powerful sovereign, able to assure the people a quick and easy well-being.

He’s ‘revealed’ in a reversal: the Glory of God is Communion in simplicity, which qualifies us everyone.

The ‘shape’ of the "boss" is that of the attendant, who has the freedom to step down in altitude to put the least at ease: the humanly defeated one!

Peter elbows more than others to have his say. As usual, he wants to emerge and reiterate ancient ideas, but he reveals himself as the most ridiculous of all (Mk 9:6; Lk 9:33): he’s ranting.

For him [again!] at the centre of the triptych remains Moses (Mk 9:5; Mt 17:4; Lk 9:33).

With the help of prophecies animated by fiery zeal [Elijah], according to Simon, Jesus would be one of the many who makes others practise the legalistic tradition.

At foundatiion remain the Commandments, not the Beatitudes.

The first of the apostles just does not want to understand that the Lord doesn’t impose a Covenant based on obeying, but on Resembling!

Of course, the other "great ones" were also half asleep. Who knows what they were dreaming of... then bewildered, they all look for a Jesus according to Moses and Elijah (Mk 9:8-10; Mt 17:8; Lk 9:36).

In the culture of the time, the new, observant and disruptive Prince was expected during the Feast of Huts.

He would inaugurate the rule of the chosen people over all the nations of the earth (Zk 14:16-19); in practice, the golden age.

In Judaism, the Feast of Booths commemorated the ‘Mirabilia Dei’ of the Exodus [Lk 9:31: here, the new and personalised liberation from the land of slavery] and looked to the future by celebrating the prospects of victory for the protagonist ethnicity.

But the Kingdom of the Lord is not an empire affected by prodigious and immediate verticalism.

To build the Church of God there are no shortcuts, no numb safety points, and there sitting quiet - at a safe distance - by raving about accolades.

[2nd Sunday in Lent, Transfiguration of the Lord]

Against the current Transfiguration: Faith and Metamorphosis

(Mt 17:1-9; Mk 9:2-13; Lk 9:28-36)

"The mountain - Tabor like Sinai - is the place of closeness with God. It is the elevated space, compared to everyday existence, where one can breathe the pure air of creation. It is the place of prayer, where one can be in the presence of the Lord, like Moses and like Elijah, who appear next to the transfigured Jesus and speak with Him of the "exodus" that awaits Him in Jerusalem, that is, of His Passover. The Transfiguration is an event of prayer: by praying, Jesus immerses himself in God, unites himself intimately with Him, adheres with his own human will to the Father's will of love, and thus light invades Him and the truth of His being appears visibly: He is God, Light from Light. Jesus' robe also becomes white and blazing. This brings to mind Baptism, the white robe worn by the neophytes. He who is reborn in Baptism is clothed with light, anticipating the heavenly existence, which Revelation represents with the symbol of the white garments (cf. Rev 7:9, 13). Here is the crucial point: the transfiguration is an anticipation of the resurrection, but this presupposes death. Jesus manifests his glory to the Apostles, so that they have the strength to face the scandal of the cross, and understand that it is necessary to go through many tribulations to reach the Kingdom of God. The voice of the Father, resounding from on high, proclaims Jesus his beloved Son as at the Baptism in the Jordan, adding: "Listen to him" (Mt 17:5). To enter eternal life, one must listen to Jesus, follow him on the way of the cross, carrying in one's heart like him the hope of the resurrection. "Spe salvi", saved in hope. Today we can say: 'Transfigured in hope'" [Pope Benedict].

In biblical language, the experience of "the Mount" is an icon of the encounter between God and man. It is like losing one's mind, but in a very practical way - not at all visionary.

The Master imposes it on the three eminent figures of the first communities, not because he considers them to be the chosen ones, but the exact opposite: he realises that it is his captains who need verification.

The Synoptic Gospels do not speak of transfiguration at all, but of "Metamorphosis" [Greek text of Mt 17:2 and Mk 9:2]: passage in a different form.

In particular Lk 9:29 emphasises that "the appearance of his face became other" [Greek text]. Not because of a paroxysmal state.

It sounds crazy, but the hieratic magnificence of the Eternal reveals itself against the grain: in the image of the resigned henchman.

The experience of divine glory is unbearable for the eminent disciples - not in reference to physical flashes of light.

As in oriental icons, they find themselves face down on the ground. "And hearing the disciples fell on their faces and were greatly seized with fear" (Mt 17:6).

In the culture of the ancient East it meant precisely: 'defeated' in their aspirations - and afraid. Afraid that they too would be called to the gift of self: Mt 17:6; Mk 9:6; Lk 9:34-36.

The vertigo of experiencing God was not what they cultivated and wanted.

The dazzling glimmer referred to in the passage (Mt 17:2.5; Mk 9:3; Lk 9:29) is that of a Revelation that opens one's eyes to the "impossible" identity of the Son.

He was popularly expected to resemble David, a powerful ruler, able to ensure the people's easy and ready welfare.

He reveals himself in reverse. A glaring manifestation of God is: Communion in simplicity, which qualifies us all.

The form of the 'leader' is that of the caretaker, who has the freedom to step down to make the least comfortable: the humanly defeated!

Peter struggles more than others to have his say. As usual, he wants to emerge and reiterate old ideas, but he reveals himself as the most ridiculous of all (Mk 9:6; Lk 9:33): he rambles.

For him [again!] at the centre of the triptych remains Moses (Mt 17:4; Mk 9:5; Lk 9:33).

With the help of prophecies animated by fiery zeal [Elijah], according to Simon Jesus would be one of many who would have the legalistic tradition practised.

The Commandments, not the Beatitudes, remain the foundation.

The first of the apostles just doesn't want to understand that the Lord does not impose a Covenant based on obeying, but on Resembling!

Of course, the other "great ones" were also asleep. Who knows what they were dreaming of... then lost they all look for a Jesus according to Moses and Elijah (Mt 17:8; Mk 9:8-10; Lk 9:36).

In the culture of the time, the new observant and disruptive Prince was expected during the Feast of Booths.

He would inaugurate the rule of the chosen people over all the nations of the earth (Zech 14:16-19); in practice, the Golden Age.

In Judaism, the Feast of Tents commemorated the 'mirabilia Dei' of the Exodus [Lk 9:31: here, the new and personalised deliverance from the land of bondage] celebrating the prospects of victory.

But the Kingdom of the Lord is not an empire to be enjoyed, prodigious and immediate - otherwise taking care not to do too much harm, that is, keeping a safe distance.

No smooth-running life proposal. Rather, change of face and cosmos.

Unexpected development and passage, which, however, convinces the soul: it invites introspection and acknowledgement - thus completing us and making us wince (with perfect virtue).

To build the Church of God, there are no shortcuts, no numbing points of safety, and there to sit quietly and cultivate consensus - sheltered from wounds, or blind to other relationships.

The experience of glory is 'sub contraria specie': in the kingship that pushes down.

But in parsimony it makes us discover awe-inspiring metamorphoses - so close to our roots.

Elijah, John, Jesus: Evolution of the Sense of Community

Curved trajectory, and the model that is not the "sphere"

(Mt 17:10-13)

The experience of "the Mount" - the so-called Transfiguration - is followed by the episode of Elijah and John [cf. Mt 17:10-13 and parallel Mk 9:2-13].

Jesus introduced the disciples in view but more stubborn than the others to the perception of the Metamorphosis (Mt 17:2 Greek text) of the divine Face and to an inverted idea of the expected Messiah (vv.4-7).

The experts of the sacred Scriptures believed that the return of Elijah was to anticipate and prepare for the coming of the Kingdom of God.

Since the Lord was present, the early disciples wondered about the value of that teaching.

Even in the communities of Mt and Mk, the question arose among many from Judaism about the weight of ancient doctrines in relation to Christ.

The Gospel passage is endowed with a powerful personal, Christological specificity [the redeeming, closest brother: Go'El of the blood].

To this is added a precise communitarian significance, because Jesus identifies the figure of the prophet Elijah with the Baptist.

At the time, in the Palestinian area, economic difficulties and Roman domination forced people to retreat to an individual model of life.

The problems of subsistence and social order had resulted in a crumbling of relationship life (and bonds) both in clans and in families themselves.

Clan nuclei, which had always provided assistance, support and concrete defence for the weakest and most distressed members.

Everyone expected that the coming of Elijah and the Messiah would have a positive outcome in the reconstruction of fraternal life, which had been eroded at the time.

As it was said: "to turn the hearts of the fathers back to the sons and the hearts of the sons back to the fathers" [Mal 3:22-24 announced precisely the sending of Elijah] in order to rebuild the disintegrated coexistence.

Obviously the recovery of the people's internal sense of identity was frowned upon by the system of domination. Let alone the Jesuit figure of the Calling by Name, which would have opened the people's pious life wide to a thousand possibilities.

John had forcefully preached a rethinking of the idea of conquered freedom (the crossing of the Jordan), the rearrangement of established religious ideas (conversion and forgiveness of sins in real life, outside the Temple) and social justice.

Having an evolved project of reform in solidarity (Lk 3:7-14), in practice it was the Baptizer himself who had already fulfilled the mission of the awaited Elijah [Mt 17:10-12; Mk 9:11-13].

For this reason he had been taken out of the way: he could reassemble a whole people of outcasts - outcasts both from the circle of power and of the verticist, accommodating, servile, and collaborationist religiosity.

A watertight compartmentalised devotion, which allowed absolutely no 'remembrance' of themselves, nor of the old communitarian social order, prone to sharing.

In short, the system of things, interests, hierarchies, forced to take root in that unsatisfactory configuration. But here is Jesus, who does not bend.

Whoever has the courage to embark on a journey of biblical spirituality and Exodus learns that everyone has a different way of going out and being in the world.

So, is there a wise balance between respect for self, context, and others?

Jesus is presented by Mt to his communities as the One who wanted to continue the work of Kingdom building.

With one fundamental difference: with respect to the bearing of ethno-religious conceptions, the Master does not propose to all a kind of ideology of the body, which ends up depersonalising the eccentric gifts of the weak - those unpredictable to an established mentality, but which trace a future.

In the climate of a consolidated clan, it is not infrequently those without weight and those who know only abysses (and not summits) who come as if driven to the assent of a reassuring conformation of ideas - instead of a dynamic one - and a forge of wider acceptance.

Those who know no peaks but only poverty, precisely in times of crisis are the first to be invited by adverse circumstances to darken their view of the future.

The wretched remain the ones who are unable to look in another direction and move, charting a different destiny - precisely because of tares external to them: cultural, of tradition, of income, or 'spiritual'.

All recognisable boxes, perhaps not alarming at times, but far removed from our nature.

And right away: with the condemnation at hand [for lack of homologation].

Sentence that wants to clip the wings, annihilate the hidden and secret atmosphere that truly belongs to personal uniqueness, and lead us all - even exasperatedly.

The Lord proposes an assembly life of character, but not stubborn or targetted - not careless ... as in the extent to which it is forced to go in the same old course as always. Or in the same direction as the chieftains.

Christ wants a more luxuriant collaboration that makes good use of resources (internal and otherwise) and differences.

Arrangement for the unprecedented: so that, for example, falls or inexorable tensions are not camouflaged - on the contrary, they become opportunities, unknown and unthinkable but very fruitful for life.

Here even crises become important, indeed fundamental, in order to evolve the quality of being together - in the richness of the "polyhedron" that as Pope Francis writes "reflects the confluence of all the partialities that in it maintain their originality" [Evangelii Gaudium no. 236].

Without regenerating oneself, only by repeating and tracing collective modalities - from the sphere model (ibid.) - or from others, that is, from nomenclature, not personally re-elaborated or valorised, one does not grow; one does not move towards one's own unrepeatable mission.

One does not fill the lacerating sense of emptiness.

By attempting to manipulate characters and personalities to guide them to 'how they should be', one is not at ease with oneself or even side by side. The perception of esteem and adequacy is not conveyed to the many different ones, nor is the sense of benevolence - let alone joie de vivre.

Curved or trial-and-error trajectories suit the Father's perspective, and our unrepeatable growth.

Difference between religiosity and Faith.

To internalise and live the message:

When in your life has your sense of community grown in a sincere way and not constrained by circumstances?

How do you contribute in a convinced way to concrete fraternity - sometimes prophetic and critical (like John and Jesus)? Or have you remained with the fundamentalist zeal of Elijah and the uniting but purist zeal of the precursors of the Lord Jesus?

In all the Synoptics, the passage of the Metamorphosis of Glory is followed by the episode of the healing of the epileptic boy [in Matthew precisely after the issue of the Return of Elijah that Mark includes]. A theme that the other evangelists draw precisely from Mk 9:14-29. Let us go directly to that source, which is very instructive in order to grasp and specify the profound meaning of the subject and the essential common proposal, introduced by the Authors in the catechesis of the so-called "Transfiguration":

Faith, Prayer of attention, Healings: no holds barred

(Mk 9:14-29)

How do we adjust to powerlessness in the face of the dramas of humanity? Even in the journey of Faith, at a certain point in our journey we perceive an irrepressible need to transform ourselves.

We want to realise our being more fully, and to do good, even to others. It is an innate urge.

The need for life does not arise from reasoning: it arises spontaneously, so that new situations, other parts of us, emerge.

Change is a law of nature, of every Seed.

Such motion 'calls' to us from the depths of our Core, so that we come to change balances, convictions, ways of going about things that have had their day.

This vocation can be answered by making ourselves available, in order to discover different points of view. Even external ones, but starting from the discovery of a kind of 'new self' that actually lay in the shadows of our virtues.

Energies that we had not yet allowed to breathe.

Conversely, we may instinctively oppose this process, due to various fears, and then every affair becomes difficult; like an obstacle course.

Finally, in our itinerary of transformation we often encounter opposition from others, who may appear more experienced than us...

They appear to be experts and veterans, yet they too are 'frightened' by the fact that we do not intend to stop at the post already dictated.

In any case, the drive for change will not let go.

We will take new actions, express different opinions, show opposite sides of the personality; we will leave more room for the life wave.

No more compromises, even if others may doubt that we have become 'tortuous'.

In short, what power does the coming of the choice of Faith have in life, even amidst people's disbelief?

And - as in the Gospel passage - in the incapable scepticism [of the apostles themselves, who would be the first ones to manifest their depth]?

Even today, some old 'characters' and guides are falling by the wayside, displaced by the new onset of awareness, or by changing enigmas, and different units of measurement.

The old 'form' no longer satisfies. On the contrary, it produces malaise. But there is around - precisely - a whole system of expectations, even 'spiritual', or at least rather conformist 'religious' ones.

What is the point, if even we priests are no longer reassuring? And what does God think?

The messianicity of Christ and Salvation itself belong to the sphere of Faith and Prayer.

They are the realms of intimate listening, acute perception, trusting spousal acceptance, and liberating drive.

The Master himself - fluid and concrete - did not immerse himself in the system of rigid social [mutual] expectations of his time, and decided to step out of the 'group'.

On this point, Jesus rails against the mediocrity and peak-less action - all predictable - of his own (vv.18-19) and is forced to start again from scratch (vv.28-29).

Of course, perhaps the others also lack creative Faith without inflection and turbulence, but at least they recognise it (v.24) and with extreme reserve wish to be helped, well before becoming teachers of others (v.14).

Sometimes the very intimates of the true Master, perhaps still poorly versed in the great signs of God, seek only the hosanna of roles, and consent in the spectacular.

So much so that "having entered into His house", that is, into His Church (v.28), He must begin again to do basic catechism [perhaps pre-catechism, precisely to His leaders].

Without wanting to concede to the crowds any outside festivals, as the 'intimates' would probably have done.

The passage is structured along the lines of the early catechumenal liturgies.

The Lord wants people enslaved by normal thinking, power ideology and false religion to be brought to Him (v.19) and demands the Faith of those who lead them (vv.23-24).

The beginner goes through a life overhaul that "contorts" and "brings one to the ground".

This is because one can be plagued by dirigiste, unwise, covertly manipulative - despite being ineffective and underneath insecure - 'spiritual' guides.

Then it is a real heartbreak to discover that from childhood (v.21) we have been governed by a mortifying model - made up of easy classifications, which however do not realise, but dehumanise.

Perhaps we too have been conditioned by unwise directors.

And it was only through arduous, harrowing experiences that we discovered that precisely what we had been taught as sublime - and capable of assuring us communion with God - was, on the contrary, the primary cause of detachment from Him, and from a more harmonious and fuller personal and ecclesial existence.

In order to be liberated and rise to new life (v.27), the candidate of the path of Faith passes as if through a death - a sort of baptismal immersion, which drowns his old [de facto] paganising formation.

At the time of Mk many spoke of the expulsion of demons.

In the typology of the new baptism, the community of Rome wanted to express the goal of the Glad Tidings of the Gospels: to help people rise up - freeing themselves from the conditioning fears of evil.

That is not the real power.

In the passage, the child's deafness and muteness indicate the lack of the 'Word' that becomes an 'event' - unceasing, growing life, capable of transforming the marked, standard fate of 'earth'.

A lack that exists both among the bewildered people and - unfortunately - first and foremost among the disciples, sick of protagonism and one-sidedness.

The young man's very behaviour (vv.18.20.26) traces the existential modes of people subjugated by invincible forces, because they are self-destructive - therefore in the grip of obsessive, unrelenting lacerations.

Contrary to the quintessence of personal character.

It is a precisely heart-rending situation: that of those who discover they have been deceived by a religiosity of all-too-common convictions - with the epidermic, persuasive trick of herd or mass directions.

The coming of the Kingdom of God already meant the coming of an 'internal' power stronger than the Roman army itself, whose legions were used precisely to maintain situations of civil oppression, even religious fear.

Even today, a no-holds-barred struggle rages between the drives that induce deep-seated illnesses [like something that has taken hold of us] and the presence of the Messiah.

The two opposite poles cannot stand each other; they spark.

But the solution is not to amaze the crowds, nor is it to attempt to remake things that finally return to sacralising the status quo.

Thus, it sometimes seems that we are in no condition to initiate genuine healing processes (v.18b).

Yet evil does not give way by miracle and clamour, nor by man's force or insistence, but by attunement and Gift (v.29). From internal power-events.

Here is the space of prayer-listening.

Prayer brings one out of the confines and puts one in contact with other energies and surprises that one was not aware of: innate virtues and Grace, which allow one to see every situation with other, liberated eyes.

For solutions that solve real problems, from within, we constantly need not conformist rules, but a new reading.

Here is the dissymmetrical gaze.

Says the Tao Tê Ching (i): 'The Tao [way of conduct] that can be said is not the Eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the Eternal Name'. Master Wang Pi comments: 'An effable Tao indicates a practice.

Our life is not about the initiative of what we are already able to set up and practice - or interpret, design and predict (vv.14-19) - but about Attention (v.29).

The "mountain" to be moved [parallel v. Mt 17:20 - cf. Mt 19:20ff; Mk 10:20ff; Lk 18:21ff] is not outside, but within us.

In this way, the conformist idea that discourages us, or all obstacles (instead of harming us) will be precious opportunities for growth.

We will be at the centre of the reality of Incarnation.

To internalise and live the message:

How do you live your conflicts? What is your experience of healing?

Overcoming that "something of disbelief",

and "putting the flesh on the fire"

Miracles still exist today. But to enable the Lord to perform them there is a need for courageous prayer, capable of overcoming that "something of unbelief" that dwells in the heart of every man, even if he is a man of faith. A prayer especially for those who suffer from wars, persecutions and every other drama that shakes society today. But prayer must "put flesh on the fire", that is, involve our person and commit our whole life, to overcome unbelief [...].

Returning to the Gospel episode, the Holy Father reproposed the question of the disciples who had not been able to drive out the evil spirit from the young man: "But why could we not drive it out? This kind of demons, Jesus explained, cannot be driven out in any way except by prayer". And the boy's father "said: I believe Lord, help my unbelief". His was "a strong prayer; and this prayer, humble and strong, enables Jesus to perform the miracle. Prayer to ask for an extraordinary action,' the Pontiff explained, 'must be a prayer that involves all of us, as if we were committing our whole life to it. In prayer we must put meat on the fire'.

The Pontiff then recounted an episode that happened in Argentina: "I remember something that happened three years ago in the sanctuary of Luján. A seven-year-old girl had fallen ill, but the doctors could not find a solution. She was getting worse and worse, until one evening, the doctors said there was nothing more they could do and that she only had a few hours to live. "The father, who was an electrician, a man of faith, became like mad. And driven by that madness he took the bus and went to the sanctuary of Luján, two and a half hours by bus, seventy kilometres away. He arrived at nine in the evening and found everything closed. And he began to pray with his hands clinging to the iron gate. He was praying and crying. So he stayed the whole night. This man was fighting with God. He was really struggling with God for the healing of his maiden. Then at six in the morning he went to the terminal and took the bus. He arrived at the hospital at nine o'clock, more or less. He found his wife crying and thought the worst: what happened? I don't understand. What happened? The doctors came, his wife told him, and they said the fever is gone, she's breathing well, there's nothing.... They will only keep her another two days. But they don't understand what has happened. And this,' the Pope commented, 'still happens. There are miracles. But prayer is needed! A courageous prayer, one that struggles to reach that miracle, not those prayers out of courtesy: Ah, I will pray for you! Then a Pater Noster, an Ave Maria and I forget. No! It takes courageous prayer, like that of Abraham who wrestled with the Lord to save the city; like that of Moses who prayed with his hands up and tired praying to the Lord; like that of so many people who have faith and with faith pray, pray".

Prayer works miracles, "but," Pope Francis concluded, "we must believe it. I think we can make a beautiful prayer, not a prayer out of courtesy, but a prayer with the heart, and say to Him today throughout the day: I believe Lord! Help my unbelief. We all have unbelief in our hearts. Let us say to the Lord: I believe, I believe! You can! Help my unbelief. And when we are asked to pray for so many people who suffer in wars, in their plight as refugees, in all these dramas we pray, but with our hearts, and we say: Lord, do. I believe, Lord. But help my unbelief".

[Pope Francis, St. Martha, in L'Osservatore Romano 20-21/05/2013].

The Mount. Structure of Christian Life

Today, the Second Sunday of Lent, as we continue on the penitential journey, the liturgy invites us, after presenting the Gospel of Jesus' temptations in the desert last week, to reflect on the extraordinary event of the Transfiguration on the mountain. Considered together, these episodes anticipate the Paschal Mystery: Jesus' struggle with the tempter preludes the great final duel of the Passion, while the light of his transfigured Body anticipates the glory of the Resurrection. On the one hand, we see Jesus, fully man, sharing with us even temptation; on the other, we contemplate him as the Son of God who divinizes our humanity. Thus, we could say that these two Sundays serve as pillars on which to build the entire structure of Lent until Easter, and indeed, the entire structure of Christian life, which consists essentially in paschal dynamism: from death to life.

The mountain - Mount Tabor, like Sinai - is the place of nearness to God. Compared with daily life it is the lofty space in which to breathe the pure air of creation. It is the place of prayer in which to stand in the Lord's presence like Moses and Elijah, who appeared beside the transfigured Jesus and spoke to him of the "exodus" that awaited him in Jerusalem, that is, his Pasch. The Transfiguration is a prayer event: in praying, Jesus is immersed in God, closely united to him, adhering with his own human will to the loving will of the Father, and thus light invades him and appears visibly as the truth of his being: he is God, Light of Light. Even Jesus' raiment becomes dazzling white. This is reminiscent of the white garment worn by neophytes. Those who are reborn in Baptism are clothed in light, anticipating heavenly existence (cf. Rev 7: 9, 13). This is the crucial point: the Transfiguration is an anticipation of the Resurrection, but this presupposes death. Jesus expresses his glory to the Apostles so that they may have the strength to face the scandal of the Cross and understand that it is necessary to pass through many tribulations in order to reach the Kingdom of God. The Father's voice, which resounds from on high, proclaims Jesus his beloved Son as he did at the Baptism in the Jordan, adding: "Listen to him" (Mt 17: 5). To enter eternal life requires listening to Jesus, following him on the way of the Cross, carrying in our heart like him the hope of the Resurrection. "Spe salvi", saved in hope. Today we can say: "Transfigured in hope".

Turning now in prayer to Mary, let us recognize in her the human creature transfigured within by Christ's grace and entrust ourselves to her guidance, to walk joyfully on our path through Lent.

[Pope Benedict, Angelus, 17 February 2008]

This is also the Way of his intimates

The mystery of the Transfiguration takes place at a very precise moment in Christ's preaching of his mission, when he begins to confide to his disciples that he must "go up to Jerusalem and suffer much ... and be killed and rise again on the third day" (Mt 16:21). With reluctance they accept the first announcement of the passion and the divine Master, before repeating and confirming it, wants to give them proof of his total rootedness in the will of the Father so that before the scandal of the cross they will not succumb. The passion and death will in fact be the way by which the heavenly Father will lead "the beloved Son", raised from the dead, to glory. This will henceforth also be the way of his disciples. No one will come to the light except through the cross, symbol of the sufferings that afflict human existence. The cross is thus transformed into an instrument of atonement for the sins of all humanity. United with his Lord in love, the disciple participates in his redemptive passion.

[Pope John Paul II, homily 7 March 1993]

For the gift

The Gospel of this second Sunday of Lent (cf. Mt 17:1-9), presents to us the account of the Transfiguration of Jesus. He takes Peter, James and John with him up a high mountain, symbol of closeness to God, to open them to a fuller understanding of the mystery of his Person, that must suffer, die and then rise again. Indeed, Jesus had begun to speak to them of the suffering, death and Resurrection that awaited him, but they were unable to accept this prospect. Therefore, once they reached the summit of the mountain, Jesus immersed himself in prayer and was transfigured before the three disciples: “his face”, says the Gospel, “shone like the sun, and his clothes became white as light” (v. 2).

Through the wondrous event of the Transfiguration, the three disciples are called to recognize in Jesus the Son of God shining with glory. Thus, they advance in their knowledge of their Master, realizing that the human aspect does not express all his reality; in their eyes the otherworldly and divine dimension of Jesus is revealed. And from on High there resounds a voice that says: “This is my beloved Son.... Listen to him” (v. 5). It is the heavenly Father who confirms the “investiture” — let us call it that — that Jesus already received on the day of his Baptism in the Jordan and invites the disciples to listen to him and to follow him.

It must be emphasized that, from among the group of the Twelve, Jesus chose to take James, John and Peter with him up the mountain. He reserved for them the privilege of witnessing the Transfiguration. But why did he select these three? Because they are the holiest? No. Yet, at the hour of trial, Peter will deny him; and the two brothers James and John will ask for the foremost places in his Kingdom (cf. Mt 20:20-23). However Jesus does not choose according to our criteria, but according to his plan of love. Jesus’ love is without measure: it is love, and he chooses with that plan of love. It is a free, unconditional choice, a free initiative, a divine friendship that asks for nothing in return. And just as he called those three disciples, so today too he calls some to be close to him, to be able to bear witness. To be witnesses to Jesus is a gift we have not deserved; we may feel inadequate but we cannot back out with the excuse of our incapacity.

We have not been on Mount Tabor, we have not seen with our own eyes the face of Jesus shining like the sun. However, we too were given the Word of Salvation, faith was given to us, and we have experienced the joy of meeting Jesus in different ways. Jesus also says to us: “Rise, and have no fear” (Mt 17:7). In this world, marked by selfishness and greed, the light of God is obscured by the worries of everyday life. We often say: I do not have time to pray, I am unable to carry out a service in the parish, to respond to the requests of others.... But we must not forget that the Baptism and Confirmation we have received has made us witnesses, not because of our ability, but as a result of the gift of the Spirit.

In the favourable time of Lent, may the Virgin Mary obtain for us that docility to the Spirit which is indispensable for setting out resolutely on the path of conversion.

[Pope Francis, Angelus, 8 March 2020]

Perfection: going all the way. And new Birth

Between intimate struggle and not opposing the evil one

(Mt 5:43-48)

Jesus proclaims that our heart is not made for closed horizons, where incompatibilities are accentuated.

He forbids exclusions, and with it resentments, communication difficulties.

In us there is something more than every facet of opportunism, and instinct to retort blow by blow... to even the score... or close oneself in one's own exemplary group.

In Latin perfĭcĕre means to complete, to lead to perfection, to do completely.

We understand: here it’s essential to introduce other energies; letting mysterious virtues act... between the deepest spaces that belong to us, and the mystery of events.

Otherwise we would assimilate an external integrity model, which doesn’t flow from the Source of being and doesn’t correspond to us in essence.

Within the paradigms of perfection, the captive Uniqueness would no longer know where to go.

Diamonds seem perfect - but nothing is born of them: God's ‘perfect’ ones are those who go ‘all the way’.

Jesus doesn’t want the existence of Faith to be marked by the usual hard extrinsic struggle - made up of intimate lacerations.

There are differences; however He orders to subvert the customs of ancient wisdom and divisions (acceptable or not, friend or foe, near or far, pure and impure, sacred and profane).

The Kingdom of God, that is the community of sons - this sprout of an alternative society - is radically different because it starts from the Seed, not from external gestures; nor does it use sweeteners, to conceal the intimate confrontation.

Events spontaneously regenerate, outside and even within us; useless to force.

The growth and destination continues and will become magnificent, also thanks to the mockery and constraints set up in an adverse way.

Surrendering, giving in, putting down the armor, will make room for new joys.

Fighting what appear to be “adversaries” confuses the soul: it is precisely the stumbles on the intended path that open up and ignite the living space - normally too narrow, suffocated by obligations.

Subtle awareness and perfection that distinguishes the authentic new man in the Spirit from the barker who ignores the things of the Father and seeks laboured shortcuts, by passing favours and 'bribes' in order to immediately settle his business with God and neighbour.

Loving the enemy who [draws us out and] makes us Perfect:

If others are not as we have dreamed of, it’s fortunate: the doors slammed in the face and their goad are preparing us many other joys.

The adventure of extreme Faith is for a wounding Beauty and an abnormal, prominent Happiness.

The ‘win-or-lose’ alternative is false: one must get out of it.

Here, only those who know to wait will find their Way.

To internalize and live the message:

What awareness or purpose do you propose in involving time, perception, listening, kindness? Appear different from your disposition, to please others? Get accepted? Or become perfectly yourself, and wait for the developments that are brewing?

[Saturday 1st wk. in Lent, February 28, 2026]

Perfection: going all the way. And new Birth

Between intimate struggle and not opposing the evil one

(Mt 5:43-48)

In his first encyclical Pope Benedict wrote:

"With the centrality of love, the Christian faith has taken up what was the core of the faith of Israel and at the same time has given this core a new depth and breadth. The believing Israelite, in fact, prays every day with the words of the Book of Deuteronomy, in which he knows that the centre of his existence is enclosed: Listen, Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength' (6:4-5). Jesus united the commandment of love of God with the commandment of love of neighbour, contained in the Book of Leviticus: "You shall love your neighbour as yourself" (19:18; cf. Mk 12:29-31), making it a single precept. Since God loved us first (cf. 1 John 4:10), love is now no longer just a "commandment", but is the response to the gift of love, with which God comes to us.

In a world where the name of God is sometimes linked to vengeance or even the duty of hatred and violence, this is a message of great relevance and very concrete meaning" [Deus Caritas est, n.1].

The "victory-or-defeat" alternative is false: we must come out of it

Jesus proclaims that our heart is not made for closed horizons, where incompatibilities are accentuated.

He forbids exclusion, and with it resentments, difficulties in communication.

There is something more in us than any facet of opportunism, and the instinct to strike back blow after blow... to even the score... even to close oneself within one's own exemplary group.

In Latin perfĭcĕre means to fulfil, to complete, to lead to perfection, to do completely.

We understand it: here it is indispensable to introduce other energies; to let mysterious virtues act... between the deepest spaces that belong to us, and the mystery of events.

How for us to reach the summit of the Mount of the Beatitudes. For a new Birth, a new Beginning.

Impossible, if we do not allow an innate, primordial Wisdom to develop - magmatic, yet far more intact and inapposite.

Venturing away from one's enclosure - even out of the worldly chorus - may not make one original, but it does begin to cure our eccentric exceptionalism.

Otherwise we would assimilate an external model of integrity, which does not spring from the Source of being and does not correspond to us in essence.

Within the paradigms of perfection, the captive uniqueness would no longer know where to go. It would go round in circles believing it would climb [in religion, as on a spiral staircase, which leads to nothing: a typical mechanism of ascetic forms].

In the exasperation of models outside ourselves, we subject the soul to the style of (even ecclesiastical) celebrities.

The anxiety produced by the narrowness of charisma, of champions, of roles lacking deep harmony, will then be ready to attack us; it will present itself around the corner as an invincible adversary.

Perfect seem like diamonds - from which, however, nothing is born: God's perfect are those who go all the way.

The Tao says: 'If you want to be given everything, give up everything'.

"Everything" also means the image we are accustomed to present to others, to be liked at any cost. One has to come out of it.

A transgressive Jesus meets the Wisdom of all times, even the natural one - absolutely not conformist.

He does not want the existence of Faith to be marked by the usual hard extrinsic struggle [typical of the 'spiritual' mentality] made of intimate lacerations.

Even today - unfortunately - in many believing realities, one is still trained in the idea of the inevitable opposition between instincts to life and decent standards.

The Lord glosses over the addictive idea of devout toil, and does so by daring to supplement the ancient Scripture, almost correcting the roots of the civil and venerable identity of the people, identified in the Torah.

Several times and in succession he suggests modifying the sacred and unappealable treasure of the Law: 'It was said [...] Now I say to you'.

The differences are there, yet Jesus commands to subvert the customs of ancient wisdom, the divisions involved: acceptable or not, friends or foes, near or far, pure and impure, sacred and profane; so on.

The Kingdom of God, that is, the community of children - this offshoot of an alternative society - is radically different because it starts from the Seed, not from outward gestures; nor does it use sweeteners, to conceal the intimate clash.

It is not 'new' as the latest of wiles or inventions to be set up.... But because it supplants the whole world of one-sided artifices.

In this way: souls must take the pace of things, to grasp the very rhythm of God, who wisely creates.

Events regenerate spontaneously, outside and even within us; it is useless to force them.

The growth and destination remains and will become magnificent, even through the mockery and constraints set up against it - by the most blatant and insincere exhibitionists, or by those who seem close.

Surrendering, giving in, laying down the armour, will make room for new joys.

Fighting the 'allergists' confuses the soul: it is precisely the stumbling on the intended path that opens and ignites the vital space - normally too narrow, suffocated by obligations.

In the Tao Tê Ching we read: 'If you want to obtain something, you must first allow it to be given to others'.

The blossoming will follow the natural nature of the children: it will be without any effort or recitation of volitional, overburdened holiness (sympathetic or otherwise).

Subtle awareness and Perfection that distinguishes the authentic new man in the Spirit from the barker who ignores the things of the Father and seeks laboured shortcuts, passing favours and 'bribes' in order to immediately settle his affairs with God and neighbour.

Love the enemy who [draws us out and] makes us Perfect:

If others are not as we dreamed, it is fortunate: the doors slammed in our faces and their stinging are preparing other joys for us.

The adventure of extreme Faith is for a Beauty that wounds and an abnormal, prominent Happiness.

Here, only those who know how to wait find their Way.

To internalise and live the message:

What awareness or purpose do you set yourself in engaging time, perception, listening, kindness?

To appear different from your nature, to please others? To make yourself accepted?

Or be perfectly yourself, and wait for the developments that are brewing?

New beginning

“You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy”, we read in the Book of Leviticus (19:1). With these words and with the consequent precepts the Lord invited the People whom he had chosen to be faithful to the Covenant with him, to walk on his path; and he founded social legislation on the commandment “you shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Lev 19:18).

Then if we listen to Jesus in whom God took a mortal body to make himself close to every human being and reveal his infinite love for us, we find that same call, that same audacious objective. Indeed, the Lord says: “You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48).

But who could become perfect? Our perfection is living humbly as children of God, doing his will in practice. St Cyprian wrote: “that the godly discipline might respond to God, the Father, that in the honour and praise of living, God may be glorified in man (De zelo et livore [On jealousy and envy], 15: CCL 3a, 83).

How can we imitate Jesus? He said: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in Heaven” (Mt 5:44-45). Anyone who welcomes the Lord into his life and loves him with all his heart is capable of a new beginning. He succeeds in doing God’s will: to bring about a new form of existence enlivened by love and destined for eternity.

The Apostle Paul added: “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” (I Cor 3:16). If we are truly aware of this reality and our life is profoundly shaped by it, then our witness becomes clear, eloquent and effective. A medieval author wrote: “When the whole of man’s being is, so to speak, mingled with God’s love, the splendour of his soul is also reflected in his external aspect” (John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, XXX: PG 88, 1157 B), in the totality of life.

“Love is an excellent thing”, we read in the book the Imitation of Christ. “It makes every difficulty easy, and bears all wrongs with equanimity…. Love tends upward; it will not be held down by anything low… love is born of God and cannot rest except in God” (III, V, 3).

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 20 February 2011]

Forgiving and Giving. Are the words of Jesus realistic?

I ask myself: are Jesus’ words realistic? Is it really possible to love like God loves and to be merciful like He is?

If we look at the history of salvation, we see that the whole of God’s revelation is an unceasing and untiring love for mankind: God is like a father or mother who loves with an unfathomable love and pours it out abundantly on every creature. Jesus’ death on the Cross is the culmination of the love story between God and man. A love so great that God alone can understand it. It is clear that, compared to this immeasurable love, our love will always be lacking. But when Jesus calls us to be merciful like the Father, he does not mean in quantity! He asks his disciples to become signs, channels, witnesses of his mercy.

The Church can be nothing other than a sacrament of God’s mercy in the world, at every time and for all of mankind. Every Christian, therefore, is called to be a witness of mercy, and this happens along the path of holiness. Let us think of the many saints who became merciful because they allowed their hearts to be filled with divine mercy. They embodied the Lord’s love, pouring it into the multiple needs of a suffering humanity. Within the flourishing of many forms of charity you can see the reflection of Christ’s merciful face.

We ask ourselves: What does it mean for disciples to be merciful? Jesus explains this with two verbs: “forgive” (Lk 6:37) and “give” (v. 38).

Mercy is expressed, first of all, in forgiveness: “Judge not, and you will not be judged; condemn not, and you will not be condemned; forgive, and you will be forgiven” (v. 37). Jesus does not intend to undermine the course of human justice, he does, however, remind his disciples that in order to have fraternal relationships they must suspend judgment and condemnation. Forgiveness, in fact, is the pillar that holds up the life of the Christian community, because it shows the gratuitousness with which God has loved us first.

The Christian must forgive! Why? Because he has been forgiven. All of us who are here today, in the Square, we have been forgiven. There is not one of us who, in our own life, has had no need of God’s forgiveness. And because we have been forgiven, we must forgive. We recite this every day in the Our Father: “Forgive us our sins; forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us”. That is, to forgive offenses, to forgive many things, because we have been forgiven of many offenses, of many sins. In this way it is easy to forgive: if God has forgiven me, why do I not forgive others? Am I greater than God? This pillar of forgiveness shows us the gratuitousness of the love of God, who loved us first. Judging and condemning a brother who sins is wrong. Not because we do not want to recognize sin, but because condemning the sinner breaks the bond of fraternity with him and spurns the mercy of God, who does not want to renounce any of his children. We do not have the power to condemn our erring brother, we are not above him: rather, we have a duty to recover the dignity of a child of the Father and to accompany him on his journey of conversion.

Jesus also indicates a second pillar to us who are his Church: “to give”. Forgiveness is the first pillar; giving is the second pillar. “Give, and it will be given to you.... For the measure you give will be the measure you get back” (v. 38). God gives far beyond our merits, but He will be even more generous with those who have been generous on earth. Jesus does not say what will happen to those who do not give, but the image of the “measure” is a warning: with the measure that we give, it is we who determine how we will be judged, how we will be loved. If we look closely, there is a coherent logic: the extent to which you receive from God, you give to your brother, and the extent to which you give to your brother, you will receive from God!

Merciful love is therefore the only way forward. We all have a great need to be a bit more merciful, to not speak ill of others, to not judge, to not “sting” others with criticism, with envy and jealousy. We must forgive, be merciful, and live our lives with love.

This love enables Jesus’ disciples to never lose the identity they received from Him, and to recognize themselves as children of the same Father. In the love that they practice in life we see reflected that Mercy that will never end (cf. 1 Cor 13:1-12). Do not forget this: mercy is a gift; forgiveness and giving. In this way, the heart expands, it grows with love. While selfishness and anger make the heart small, they make it harden like a stone. Which do you prefer? A heart of stone or a heart full of love? If you prefer a heart full of love, be merciful!

[Pope Francis, General Audience 21 September 2016]

Doing a good deed almost instinctively gives rise to the desire to be esteemed and admired for the good action, in other words to gain a reward. And on the one hand this closes us in on ourselves and on the other, it brings us out of ourselves because we live oriented to what others think of us or admire in us (Pope Benedict)

Quando si compie qualcosa di buono, quasi istintivamente nasce il desiderio di essere stimati e ammirati per la buona azione, di avere cioè una soddisfazione. E questo, da una parte rinchiude in se stessi, dall’altra porta fuori da se stessi, perché si vive proiettati verso quello che gli altri pensano di noi e ammirano in noi (Papa Benedetto)

Since God has first loved us (cf. 1 Jn 4:10), love is now no longer a mere “command”; it is the response to the gift of love with which God draws near to us [Pope Benedict]

Siccome Dio ci ha amati per primo (cfr 1 Gv 4, 10), l'amore adesso non è più solo un « comandamento », ma è la risposta al dono dell'amore, col quale Dio ci viene incontro [Papa Benedetto]

Another aspect of Lenten spirituality is what we could describe as "combative" […] where the "weapons" of penance and the "battle" against evil are mentioned. Every day, but particularly in Lent, Christians must face a struggle […] (Pope Benedict)

Un altro aspetto della spiritualità quaresimale è quello che potremmo definire "agonistico" […] là dove si parla di "armi" della penitenza e di "combattimento" contro lo spirito del male. Ogni giorno, ma particolarmente in Quaresima, il cristiano deve affrontare una lotta […] (Papa Benedetto)

Jesus wants to help his listeners take the right approach to the prescriptions of the Commandments given to Moses, urging them to be open to God who teaches us true freedom and responsibility through the Law. It is a matter of living it as an instrument of freedom (Pope Francis)

Gesù vuole aiutare i suoi ascoltatori ad avere un approccio giusto alle prescrizioni dei Comandamenti dati a Mosè, esortando ad essere disponibili a Dio che ci educa alla vera libertà e responsabilità mediante la Legge. Si tratta di viverla come uno strumento di libertà (Papa Francesco)

In the divine attitude justice is pervaded with mercy, whereas the human attitude is limited to justice. Jesus exhorts us to open ourselves with courage to the strength of forgiveness, because in life not everything can be resolved with justice. We know this (Pope Francis)

Nell’atteggiamento divino la giustizia è pervasa dalla misericordia, mentre l’atteggiamento umano si limita alla giustizia. Gesù ci esorta ad aprirci con coraggio alla forza del perdono, perché nella vita non tutto si risolve con la giustizia; lo sappiamo (Papa Francesco)

The true prophet does not obey others as he does God, and puts himself at the service of the truth, ready to pay in person. It is true that Jesus was a prophet of love, but love has a truth of its own. Indeed, love and truth are two names of the same reality, two names of God (Pope Benedict)

Il vero profeta non obbedisce ad altri che a Dio e si mette al servizio della verità, pronto a pagare di persona. E’ vero che Gesù è il profeta dell’amore, ma l’amore ha la sua verità. Anzi, amore e verità sono due nomi della stessa realtà, due nomi di Dio (Papa Benedetto)

“Give me a drink” (v. 7). Breaking every barrier, he begins a dialogue in which he reveals to the woman the mystery of living water, that is, of the Holy Spirit, God’s gift [Pope Francis]

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.