don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Samaritan woman, weary at the well. Or Jesus, fresh Spring within reach. Assent Faith, Bridal Faith, Faith Trigger, Faith Astonishment

Second Sunday in Lent

Second Lent Sunday (year A) [1st March 2026]

*First Reading from the Book of Genesis (12:1-4)

The few lines we have just read constitute the first act of the entire adventure of our faith: the faith of the Jews, then, in chronological order, of Christians and Muslims. We are in the second millennium BC. Abram* lived in Chaldea, that is, in Iraq, and more precisely in the extreme south-east of Iraq, in the city of UR, in the Euphrates valley, near the Persian Gulf. He lived with his wife Sarai, his father Terah, his brothers (Nahor and Aran) and his nephew Lot. Abram was seventy-five years old, his wife Sarai sixty-five; they had no children and, given their age, would never have any. One day, his old father, Terah, set out on the road with Abram, Sarai and his nephew Lot. The caravan travelled up the Euphrates valley from the south-east to the north-west with the intention of then descending towards the land of Canaan. There was a shorter route, of course, connecting the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, but it crossed a huge desert. Terah and Abram preferred to travel along the 'Fertile Crescent', which lives up to its name. The last stop in the north-west is called Harran. It is there that old Terah dies. And it is above all there that, for the first time, about 4000 years ago, around 1850 BC, God spoke to Abram.

"Leave your land," says our liturgical translation, but it omits the first two words, probably to avoid excessive interpretations, which have not always been avoided. In fact, in Hebrew, the first two words are "You, go!" Grammatically, they mean nothing else. It is a personal appeal, a setting aside: it is a true story of vocation. And it is to this simple invitation that Abram responded. It is often translated as "Go for yourself," but this is already an over-interpretation of faith. "Go for yourself": we must be aware that we are moving away from the literal meaning of the text and entering into an interpretation, a spiritual commentary. It is Rashi, the great 11th-century Jewish commentator (in Troyes in Champagne), who translates "Go for yourself, for your own good and for your happiness". In fact, this is what Abram will experience in the course of the days. If God calls man, it is for man's own good, not for anything else! God's merciful plan for humanity is contained in these two little words: 'for you'. God already reveals himself as the one who desires the good of man, of all men**; if there is one thing to remember, it is this! 'Go for yourself': a believer is someone who knows that, whatever happens, God is leading him towards his fulfilment, towards his happiness. So here are God's first words to Abram, the words that set off his whole adventure... and ours! Go, leave your country, your family and your father's house, and go to the land that I will show you. And what follows are only promises: I will make you a great nation, I will bless you, I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing... All the families of the earth shall be blessed in you. Abram is torn from his natural destiny, chosen, elected by God, invested with a universal vocation. Abram, for the moment, is a nomad, perhaps rich, but unknown, and he has no children; his wife Sarai is well past childbearing age. Yet it is he whom God chooses to become the father of a great people. This is what that 'for you' meant earlier: God promises him everything that, at that time, constitutes a man's happiness: numerous descendants and God's blessing. But this happiness promised to Abram is not only for him: in the Bible, no vocation, no calling is ever for the selfish interest of the one who is called. This is one of the criteria of an authentic vocation: every vocation is always for a mission in the service of others. Here is this phrase: 'In you all the families of the earth shall be blessed'. It means at least two things: first, your success will be such that you will be taken as an example: when people want to wish someone happiness, they will say, 'May you be as happy as Abram'. Second, this 'in you' can mean through you; and then it means 'through you, I, God, will bless all the families of the earth'. God's plan for happiness passes through Abram, but it surpasses him, it overflows him; it concerns all humanity: 'In you, through you, all the families of the earth will be blessed'. Throughout the history of Israel, the Bible will remain faithful to this first discovery: Abraham and his descendants are the chosen people, chosen by God but for the benefit of all humanity, from the first day, from the first word to Abraham. The fact remains that other nations are free not to enter into this blessing; this is the meaning of the seemingly curious phrase: "I will bless those who bless you, and those who curse you I will curse" (12:3). It is a way of expressing our freedom: anyone who wishes to do so can share in the blessing promised to Abram, but no one is obliged to accept it! The time for the great departure has come; the text is extraordinary in its sobriety: it simply says, "Abram departed as the Lord had commanded him" (12:4), and Lot went with him. One cannot be more laconic! This departure, at the simple call of God, is the most beautiful proof of faith; four thousand years later, we can say that our faith finds its source in that of Abraham; and if our whole lives are illuminated by faith, it is thanks to him! And all human history becomes the place of the fulfilment of God's promises to Abraham: a slow, progressive fulfilment, but certain and sure.

Notes: *At the beginning of this great adventure, the man we call Abraham was still called only Abram; later, after years of pilgrimage, he would receive from God the new name by which we know him: Abraham, which means 'father of multitudes'.

**This 'for you' should not be understood as exclusive, even if it was not immediately understood at first. Only after a long discovery of God's Covenant were believers able to access the full truth: God's plan concerns not only Abraham and his descendants, but all of humanity. This is what we call the universality of God's plan. This discovery dates back to the Exile in Babylon in the 6th century BC.

Addition: At another point in Abraham's life, when he offers Isaac as a sacrifice, God uses the same expression, "Go," to give him the strength to face the trial, reminding him of the journey he has already made. The Letter to the Hebrews takes Abraham's departure to explain what faith is (cf. Heb 11:8-12).

*Responsorial Psalm (32/33)

The word 'love' appears three times in these few verses, and this insistence responds very well to the first reading: Abraham is the first in all human history to discover that God is love and that he has plans for the happiness of humanity. However, it was necessary to believe in this extraordinary revelation. And Abraham believed, he agreed to trust in the words of the future that God announced to him. An old man without children, yet he would have had every reason to doubt this incredible promise from God. God says to him: Leave your country... I will make you a great nation. And the text of Genesis concludes that Abram left as the Lord had told him.

This is a beautiful example for us at the beginning of Lent: we should believe in all circumstances that God has plans for our happiness. This was precisely the meaning of the phrase pronounced over us on Ash Wednesday: "Repent and believe in the Gospel." To convert means to believe once and for all that the Newness is that God is Love. Jeremiah said on behalf of God: 'I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope' (Jer 29:11). Thus, the first two Sundays of Lent invite us to make a choice: on the first Sunday, we read in the book of Genesis the story of Adam: the man who suspects God in the face of a prohibition (not to eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil), imagining that God might even be jealous! These are the insinuations of the serpent, which means poison. For this second Sunday of Lent, however, we read the story of Abraham, the believer. A little further on, the book of Genesis says of him: Abram believed in the Lord, who counted him as righteous. And, to help us follow the same path as Abraham, this psalm suggests words of trust: 'The eye of the Lord is on those who fear him, on those who hope in his love to deliver them from death'. At the beginning, we read: 'The earth is full of love...' and then the expression 'those who fear him' is explained in the next line: 'those who hope in his love', so far from fear, quite the opposite! The temptation is to want to be free and do whatever we want... to obey only ourselves. All this comes from experience, and that is why the chosen people can say: 'the eye of the Lord is on those who fear him, on those who hope in his love' because God has watched over them like a father over his children. When it says that he frees them from death, it is not talking about biological death. We must remember that at the time this psalm was composed, individual death was not considered a tragedy; what mattered was the survival of the people in the certainty that God would keep his people alive. At all times, and especially in times of trial, God accompanies his people and delivers them from death. The reference to times of famine is certainly an allusion to the manna that God sent during the Exodus, when hunger became threatening. All the people can bear witness to this care of God in every age; and when we sing "The word of the Lord is upright, and all his work is done in faithfulness," we are simply repeating the name of the merciful and faithful God who revealed himself to Moses (Ex 34:6). The conclusion is a prayer of trust: "May your love be upon us, Lord, as we hope in you" is an invitation to believers to offer themselves to this love.

*Second reading from the second letter of St Paul the Apostle to Timothy (1:8b-10)

Paul is in prison in Rome, he knows that he will soon be executed, and here he gives his last recommendations to Timothy: "My dear son, with the strength of God, suffer with me for the Gospel." This suffering is the persecution that is inevitable for a true disciple of Christ, as Jesus had said (cf. Mk 8:34-35). Both at the beginning and at the end of the passage, there is a reference to the Gospel, which is presented as an inclusion. In the middle, framed by these two identical references, Paul explains what this Gospel is. He uses the word Gospel in its etymological sense of good news, just as Jesus himself said at the beginning of his preaching in Galilee: "Repent and believe in the Gospel, the Good News" means that Christian preaching is the proclamation that the kingdom of God has finally been inaugurated. For Paul, it is in the central sentence of our text that we discover what the Gospel consists of: ultimately, it can be summed up in a few words: God has saved us through Jesus Christ. *"God saved us": it is a past tense, something that has been accomplished; but at the same time, in order for people to enter into this salvation, it is necessary that the Gospel be proclaimed to them. It is therefore truly a holy vocation that has been entrusted to us: "God saved us and called us to a holy vocation" (1:9). It is a holy vocation because it is entrusted to us by God who is holy; it is a holy vocation because it involves proclaiming God's plan; it is a holy vocation because God's plan needs our collaboration: each of us must play our part, as Paul says. But the expression "holy vocation" also means something else: God's plan for us, for humanity, is so great that it fully deserves this name. The particular vocation of the apostles is part of this universal vocation of humanity.

*"God has saved us": in the Bible, the verb "to save" always means "to liberate". It took a long and gradual discovery of this reality on the part of the people of the Covenant: God wants man to be free and intervenes incessantly to free us from every form of slavery. There are many types of slavery: political slavery, such as servitude in Egypt or exile in Babylon; and each time Israel recognised God's work in its liberation; social slavery, and the Law of Moses, as the prophets never cease to call for the conversion of hearts so that every person may live in dignity and freedom; religious slavery, which is even more insidious. The prophets never ceased to transmit this will of God to see humanity finally freed from all its chains. Paul says that Jesus has freed us even from death: Jesus "has conquered death and brought life and immortality to light through the gospel" (1:10). Paul affirms this

as he prepares to be executed. Jesus himself died, and we too will all die. Jesus, therefore, is not speaking of biological death. What victory is he referring to then? Jesus, filled with the Holy Spirit, gives us his own life, which we can share spiritually, and which nothing can destroy, not even biological death. His Resurrection is proof that biological death cannot destroy it, so for us biological death will be nothing more than a passage towards the light that never sets: in the funeral liturgy we say: "Life is not taken away, but transformed". If biological death is part of our physical constitution, made of dust – as the book of Genesis says – it cannot separate us from Jesus Christ (cf. Rom 8:39). In us there is a relationship with God that nothing, not even biological death, can destroy: this is what St John calls 'eternal life'.

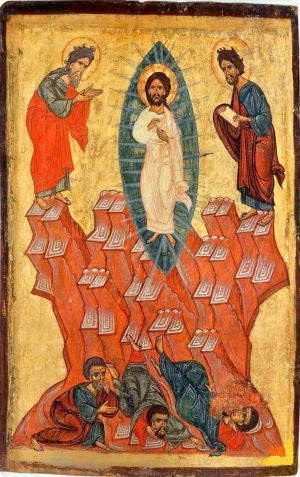

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (17:1-9)

"Jesus took Peter, James and John with him": once again we are faced with the mystery of God's choices. It was to Peter that Jesus had said shortly before, in Caesarea: "You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the powers of death will not prevail against it" (Mt 16:18). But Peter is accompanied by two brothers, James and John, the two sons of Zebedee. "And Jesus led them up a high mountain, apart": on a high mountain Moses had received the Revelation of the God of the Covenant and the tablets of the Law; that Law which was to progressively educate the people of the Covenant to live in the love of God and of their brothers and sisters. On the same mountain, Elijah had received the revelation of the God of tenderness in the gentle breeze... Moses and Elijah, the two pillars of the Old Testament... On the high mountain of the Transfiguration, Peter, James and John, the pillars of the Church, receive the revelation of the God of tenderness incarnate in Jesus: "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased". And this revelation is granted to them to strengthen their faith before the storm of the Passion. Peter will write about it later (cf. 2 Pt 1:16-18).

The expression "my beloved Son: listen to him" designates Jesus as the Messiah: to Jewish ears, this simple phrase is a triple allusion to the Old Testament, because it recalls three very different texts, but ones that are well present in everyone's memory; all the more so because the expectation was intense at the time of Jesus' coming and hypotheses were multiplying: we have proof of this in the numerous questions addressed to Jesus in the Gospels. "Son" was the title usually given to kings, and the Messiah was expected to have the characteristics of a king descended from David, who would finally reign on the throne of Jerusalem, which had been without a king for a long time. The beloved, in whom I am well pleased, evoked a completely different context: it refers to the "Songs of the Servant" in the book of Isaiah; it meant that Jesus is the Messiah, no longer in the manner of a king, but of a Servant, in the sense of Isaiah (Is 42:1). 'Listen to him' meant something else: that Jesus is the Messiah-Prophet in the sense that Moses, in the Book of Deuteronomy, had announced to the people: 'The Lord your God will raise up for you, from among your own brothers, a prophet like me; you shall listen to him' (Dt 18:15). ' "Let us make three tents": this phrase of Peter suggests that the episode of the Transfiguration may have taken place during the Feast of Tabernacles, or at least in a climate linked to it, a feast celebrated in memory of the crossing of the desert during the Exodus and the Covenant made with God, in the fervent experience that the prophets would later call the betrothal of the people to the God of tenderness and fidelity. During this feast, people lived in huts for eight days, waiting and imploring a new manifestation of God that would be fulfilled with the coming of the Messiah. On the Mount of Transfiguration, the three apostles suddenly find themselves faced with this revelation of the mystery of Jesus: it is not surprising that they are seized with the fear that grips every man before the manifestation of the holy God. nor is it surprising that Jesus raises them up and reassures them: the Old Testament had already revealed to the people of the Covenant that the most holy God is the God who is close to man and that fear is not appropriate. But the revelation of the mystery of the Messiah, in all its dimensions, is not yet within everyone's reach; Jesus orders them not to tell anyone for the time being, before the Son of Man has risen from the dead. By saying this last sentence, Jesus confirms the revelation that the three disciples have just received: he is truly the Messiah whom the prophet Daniel saw in the form of a man, coming on the clouds of heaven (cf. Dan 7:13-14). Daniel himself presents the Son of Man not as a solitary individual, but as a people, whom he calls "the people of the Most High". The fulfilment is even more beautiful than the promise: in Jesus, Man-God, it is the whole of humanity that will receive this eternal kingship and be eternally transfigured. But Jesus said clearly: Tell no one anything before the Resurrection. Only after Jesus' Resurrection will the apostles be able to bear witness to it.

+Giovanni D'Ercole

Against the tide Transfiguration

Faith and Metamorphosis

(Mk 9:2-13)

In biblical language, the experience of «the Mount» is an icon of the Encounter between God and man. Yes, for us it’s like “losing our minds”, but in a very practical way - not at all visionary.

The Master imposes it on the three eminent figures of the first communities, not because he considers them the chosen ones, but the exact opposite: he realizes that it’s his captains who need verification.

The synoptic Gospels do not speak of Transfiguration any, but of «Metamorphosis» [Greek text of Mk 9:2 and Mt 17:2]: a passing under a different ‘form’.

In particular, Lk 9:29 emphasizes that «the appearance of his face became ‘other’». Not because of a paroxysmal state.

It sounds crazy, but the hieratic magnificence of the Eternal One is revealed against the tide: in the image of the humble servant.

The experience of divine Glory is unsustainable for the eminent disciples - not in reference to physical flashes of light.

As in Oriental icons, they find themselves face to earth [Mt 17:6 - in ancient Eastern culture it meant precisely: "defeated" in their aspirations] and frightened. Fearful of being they too called to the gift of self (Mk 9:6; Mt 17:6; Lk 9:34-36).

The vertigo of the experience of God was not what they cultivated and wanted.

The dazzling light to which the passage refers (Mk 9:3; Mt 17:2.5; Lk 9:29) is that of a Revelation that opens our eyes to the "impossible" identity of the Son.

He was popularly expected as resembling David, powerful sovereign, able to assure the people a quick and easy well-being.

He’s ‘revealed’ in a reversal: the Glory of God is Communion in simplicity, which qualifies us everyone.

The ‘shape’ of the "boss" is that of the attendant, who has the freedom to step down in altitude to put the least at ease: the humanly defeated one!

Peter elbows more than others to have his say. As usual, he wants to emerge and reiterate ancient ideas, but he reveals himself as the most ridiculous of all (Mk 9:6; Lk 9:33): he’s ranting.

For him [again!] at the centre of the triptych remains Moses (Mk 9:5; Mt 17:4; Lk 9:33).

With the help of prophecies animated by fiery zeal [Elijah], according to Simon, Jesus would be one of the many who makes others practise the legalistic tradition.

At foundatiion remain the Commandments, not the Beatitudes.

The first of the apostles just does not want to understand that the Lord doesn’t impose a Covenant based on obeying, but on Resembling!

Of course, the other "great ones" were also half asleep. Who knows what they were dreaming of... then bewildered, they all look for a Jesus according to Moses and Elijah (Mk 9:8-10; Mt 17:8; Lk 9:36).

In the culture of the time, the new, observant and disruptive Prince was expected during the Feast of Huts.

He would inaugurate the rule of the chosen people over all the nations of the earth (Zk 14:16-19); in practice, the golden age.

In Judaism, the Feast of Booths commemorated the ‘Mirabilia Dei’ of the Exodus [Lk 9:31: here, the new and personalised liberation from the land of slavery] and looked to the future by celebrating the prospects of victory for the protagonist ethnicity.

But the Kingdom of the Lord is not an empire affected by prodigious and immediate verticalism.

To build the Church of God there are no shortcuts, no numb safety points, and there sitting quiet - at a safe distance - by raving about accolades.

[2nd Sunday in Lent, Transfiguration of the Lord]

Against the current Transfiguration: Faith and Metamorphosis

(Mt 17:1-9; Mk 9:2-13; Lk 9:28-36)

"The mountain - Tabor like Sinai - is the place of closeness with God. It is the elevated space, compared to everyday existence, where one can breathe the pure air of creation. It is the place of prayer, where one can be in the presence of the Lord, like Moses and like Elijah, who appear next to the transfigured Jesus and speak with Him of the "exodus" that awaits Him in Jerusalem, that is, of His Passover. The Transfiguration is an event of prayer: by praying, Jesus immerses himself in God, unites himself intimately with Him, adheres with his own human will to the Father's will of love, and thus light invades Him and the truth of His being appears visibly: He is God, Light from Light. Jesus' robe also becomes white and blazing. This brings to mind Baptism, the white robe worn by the neophytes. He who is reborn in Baptism is clothed with light, anticipating the heavenly existence, which Revelation represents with the symbol of the white garments (cf. Rev 7:9, 13). Here is the crucial point: the transfiguration is an anticipation of the resurrection, but this presupposes death. Jesus manifests his glory to the Apostles, so that they have the strength to face the scandal of the cross, and understand that it is necessary to go through many tribulations to reach the Kingdom of God. The voice of the Father, resounding from on high, proclaims Jesus his beloved Son as at the Baptism in the Jordan, adding: "Listen to him" (Mt 17:5). To enter eternal life, one must listen to Jesus, follow him on the way of the cross, carrying in one's heart like him the hope of the resurrection. "Spe salvi", saved in hope. Today we can say: 'Transfigured in hope'" [Pope Benedict].

In biblical language, the experience of "the Mount" is an icon of the encounter between God and man. It is like losing one's mind, but in a very practical way - not at all visionary.

The Master imposes it on the three eminent figures of the first communities, not because he considers them to be the chosen ones, but the exact opposite: he realises that it is his captains who need verification.

The Synoptic Gospels do not speak of transfiguration at all, but of "Metamorphosis" [Greek text of Mt 17:2 and Mk 9:2]: passage in a different form.

In particular Lk 9:29 emphasises that "the appearance of his face became other" [Greek text]. Not because of a paroxysmal state.

It sounds crazy, but the hieratic magnificence of the Eternal reveals itself against the grain: in the image of the resigned henchman.

The experience of divine glory is unbearable for the eminent disciples - not in reference to physical flashes of light.

As in oriental icons, they find themselves face down on the ground. "And hearing the disciples fell on their faces and were greatly seized with fear" (Mt 17:6).

In the culture of the ancient East it meant precisely: 'defeated' in their aspirations - and afraid. Afraid that they too would be called to the gift of self: Mt 17:6; Mk 9:6; Lk 9:34-36.

The vertigo of experiencing God was not what they cultivated and wanted.

The dazzling glimmer referred to in the passage (Mt 17:2.5; Mk 9:3; Lk 9:29) is that of a Revelation that opens one's eyes to the "impossible" identity of the Son.

He was popularly expected to resemble David, a powerful ruler, able to ensure the people's easy and ready welfare.

He reveals himself in reverse. A glaring manifestation of God is: Communion in simplicity, which qualifies us all.

The form of the 'leader' is that of the caretaker, who has the freedom to step down to make the least comfortable: the humanly defeated!

Peter struggles more than others to have his say. As usual, he wants to emerge and reiterate old ideas, but he reveals himself as the most ridiculous of all (Mk 9:6; Lk 9:33): he rambles.

For him [again!] at the centre of the triptych remains Moses (Mt 17:4; Mk 9:5; Lk 9:33).

With the help of prophecies animated by fiery zeal [Elijah], according to Simon Jesus would be one of many who would have the legalistic tradition practised.

The Commandments, not the Beatitudes, remain the foundation.

The first of the apostles just doesn't want to understand that the Lord does not impose a Covenant based on obeying, but on Resembling!

Of course, the other "great ones" were also asleep. Who knows what they were dreaming of... then lost they all look for a Jesus according to Moses and Elijah (Mt 17:8; Mk 9:8-10; Lk 9:36).

In the culture of the time, the new observant and disruptive Prince was expected during the Feast of Booths.

He would inaugurate the rule of the chosen people over all the nations of the earth (Zech 14:16-19); in practice, the Golden Age.

In Judaism, the Feast of Tents commemorated the 'mirabilia Dei' of the Exodus [Lk 9:31: here, the new and personalised deliverance from the land of bondage] celebrating the prospects of victory.

But the Kingdom of the Lord is not an empire to be enjoyed, prodigious and immediate - otherwise taking care not to do too much harm, that is, keeping a safe distance.

No smooth-running life proposal. Rather, change of face and cosmos.

Unexpected development and passage, which, however, convinces the soul: it invites introspection and acknowledgement - thus completing us and making us wince (with perfect virtue).

To build the Church of God, there are no shortcuts, no numbing points of safety, and there to sit quietly and cultivate consensus - sheltered from wounds, or blind to other relationships.

The experience of glory is 'sub contraria specie': in the kingship that pushes down.

But in parsimony it makes us discover awe-inspiring metamorphoses - so close to our roots.

Elijah, John, Jesus: Evolution of the Sense of Community

Curved trajectory, and the model that is not the "sphere"

(Mt 17:10-13)

The experience of "the Mount" - the so-called Transfiguration - is followed by the episode of Elijah and John [cf. Mt 17:10-13 and parallel Mk 9:2-13].

Jesus introduced the disciples in view but more stubborn than the others to the perception of the Metamorphosis (Mt 17:2 Greek text) of the divine Face and to an inverted idea of the expected Messiah (vv.4-7).

The experts of the sacred Scriptures believed that the return of Elijah was to anticipate and prepare for the coming of the Kingdom of God.

Since the Lord was present, the early disciples wondered about the value of that teaching.

Even in the communities of Mt and Mk, the question arose among many from Judaism about the weight of ancient doctrines in relation to Christ.

The Gospel passage is endowed with a powerful personal, Christological specificity [the redeeming, closest brother: Go'El of the blood].

To this is added a precise communitarian significance, because Jesus identifies the figure of the prophet Elijah with the Baptist.

At the time, in the Palestinian area, economic difficulties and Roman domination forced people to retreat to an individual model of life.

The problems of subsistence and social order had resulted in a crumbling of relationship life (and bonds) both in clans and in families themselves.

Clan nuclei, which had always provided assistance, support and concrete defence for the weakest and most distressed members.

Everyone expected that the coming of Elijah and the Messiah would have a positive outcome in the reconstruction of fraternal life, which had been eroded at the time.

As it was said: "to turn the hearts of the fathers back to the sons and the hearts of the sons back to the fathers" [Mal 3:22-24 announced precisely the sending of Elijah] in order to rebuild the disintegrated coexistence.

Obviously the recovery of the people's internal sense of identity was frowned upon by the system of domination. Let alone the Jesuit figure of the Calling by Name, which would have opened the people's pious life wide to a thousand possibilities.

John had forcefully preached a rethinking of the idea of conquered freedom (the crossing of the Jordan), the rearrangement of established religious ideas (conversion and forgiveness of sins in real life, outside the Temple) and social justice.

Having an evolved project of reform in solidarity (Lk 3:7-14), in practice it was the Baptizer himself who had already fulfilled the mission of the awaited Elijah [Mt 17:10-12; Mk 9:11-13].

For this reason he had been taken out of the way: he could reassemble a whole people of outcasts - outcasts both from the circle of power and of the verticist, accommodating, servile, and collaborationist religiosity.

A watertight compartmentalised devotion, which allowed absolutely no 'remembrance' of themselves, nor of the old communitarian social order, prone to sharing.

In short, the system of things, interests, hierarchies, forced to take root in that unsatisfactory configuration. But here is Jesus, who does not bend.

Whoever has the courage to embark on a journey of biblical spirituality and Exodus learns that everyone has a different way of going out and being in the world.

So, is there a wise balance between respect for self, context, and others?

Jesus is presented by Mt to his communities as the One who wanted to continue the work of Kingdom building.

With one fundamental difference: with respect to the bearing of ethno-religious conceptions, the Master does not propose to all a kind of ideology of the body, which ends up depersonalising the eccentric gifts of the weak - those unpredictable to an established mentality, but which trace a future.

In the climate of a consolidated clan, it is not infrequently those without weight and those who know only abysses (and not summits) who come as if driven to the assent of a reassuring conformation of ideas - instead of a dynamic one - and a forge of wider acceptance.

Those who know no peaks but only poverty, precisely in times of crisis are the first to be invited by adverse circumstances to darken their view of the future.

The wretched remain the ones who are unable to look in another direction and move, charting a different destiny - precisely because of tares external to them: cultural, of tradition, of income, or 'spiritual'.

All recognisable boxes, perhaps not alarming at times, but far removed from our nature.

And right away: with the condemnation at hand [for lack of homologation].

Sentence that wants to clip the wings, annihilate the hidden and secret atmosphere that truly belongs to personal uniqueness, and lead us all - even exasperatedly.

The Lord proposes an assembly life of character, but not stubborn or targetted - not careless ... as in the extent to which it is forced to go in the same old course as always. Or in the same direction as the chieftains.

Christ wants a more luxuriant collaboration that makes good use of resources (internal and otherwise) and differences.

Arrangement for the unprecedented: so that, for example, falls or inexorable tensions are not camouflaged - on the contrary, they become opportunities, unknown and unthinkable but very fruitful for life.

Here even crises become important, indeed fundamental, in order to evolve the quality of being together - in the richness of the "polyhedron" that as Pope Francis writes "reflects the confluence of all the partialities that in it maintain their originality" [Evangelii Gaudium no. 236].

Without regenerating oneself, only by repeating and tracing collective modalities - from the sphere model (ibid.) - or from others, that is, from nomenclature, not personally re-elaborated or valorised, one does not grow; one does not move towards one's own unrepeatable mission.

One does not fill the lacerating sense of emptiness.

By attempting to manipulate characters and personalities to guide them to 'how they should be', one is not at ease with oneself or even side by side. The perception of esteem and adequacy is not conveyed to the many different ones, nor is the sense of benevolence - let alone joie de vivre.

Curved or trial-and-error trajectories suit the Father's perspective, and our unrepeatable growth.

Difference between religiosity and Faith.

To internalise and live the message:

When in your life has your sense of community grown in a sincere way and not constrained by circumstances?

How do you contribute in a convinced way to concrete fraternity - sometimes prophetic and critical (like John and Jesus)? Or have you remained with the fundamentalist zeal of Elijah and the uniting but purist zeal of the precursors of the Lord Jesus?

In all the Synoptics, the passage of the Metamorphosis of Glory is followed by the episode of the healing of the epileptic boy [in Matthew precisely after the issue of the Return of Elijah that Mark includes]. A theme that the other evangelists draw precisely from Mk 9:14-29. Let us go directly to that source, which is very instructive in order to grasp and specify the profound meaning of the subject and the essential common proposal, introduced by the Authors in the catechesis of the so-called "Transfiguration":

Faith, Prayer of attention, Healings: no holds barred

(Mk 9:14-29)

How do we adjust to powerlessness in the face of the dramas of humanity? Even in the journey of Faith, at a certain point in our journey we perceive an irrepressible need to transform ourselves.

We want to realise our being more fully, and to do good, even to others. It is an innate urge.

The need for life does not arise from reasoning: it arises spontaneously, so that new situations, other parts of us, emerge.

Change is a law of nature, of every Seed.

Such motion 'calls' to us from the depths of our Core, so that we come to change balances, convictions, ways of going about things that have had their day.

This vocation can be answered by making ourselves available, in order to discover different points of view. Even external ones, but starting from the discovery of a kind of 'new self' that actually lay in the shadows of our virtues.

Energies that we had not yet allowed to breathe.

Conversely, we may instinctively oppose this process, due to various fears, and then every affair becomes difficult; like an obstacle course.

Finally, in our itinerary of transformation we often encounter opposition from others, who may appear more experienced than us...

They appear to be experts and veterans, yet they too are 'frightened' by the fact that we do not intend to stop at the post already dictated.

In any case, the drive for change will not let go.

We will take new actions, express different opinions, show opposite sides of the personality; we will leave more room for the life wave.

No more compromises, even if others may doubt that we have become 'tortuous'.

In short, what power does the coming of the choice of Faith have in life, even amidst people's disbelief?

And - as in the Gospel passage - in the incapable scepticism [of the apostles themselves, who would be the first ones to manifest their depth]?

Even today, some old 'characters' and guides are falling by the wayside, displaced by the new onset of awareness, or by changing enigmas, and different units of measurement.

The old 'form' no longer satisfies. On the contrary, it produces malaise. But there is around - precisely - a whole system of expectations, even 'spiritual', or at least rather conformist 'religious' ones.

What is the point, if even we priests are no longer reassuring? And what does God think?

The messianicity of Christ and Salvation itself belong to the sphere of Faith and Prayer.

They are the realms of intimate listening, acute perception, trusting spousal acceptance, and liberating drive.

The Master himself - fluid and concrete - did not immerse himself in the system of rigid social [mutual] expectations of his time, and decided to step out of the 'group'.

On this point, Jesus rails against the mediocrity and peak-less action - all predictable - of his own (vv.18-19) and is forced to start again from scratch (vv.28-29).

Of course, perhaps the others also lack creative Faith without inflection and turbulence, but at least they recognise it (v.24) and with extreme reserve wish to be helped, well before becoming teachers of others (v.14).

Sometimes the very intimates of the true Master, perhaps still poorly versed in the great signs of God, seek only the hosanna of roles, and consent in the spectacular.

So much so that "having entered into His house", that is, into His Church (v.28), He must begin again to do basic catechism [perhaps pre-catechism, precisely to His leaders].

Without wanting to concede to the crowds any outside festivals, as the 'intimates' would probably have done.

The passage is structured along the lines of the early catechumenal liturgies.

The Lord wants people enslaved by normal thinking, power ideology and false religion to be brought to Him (v.19) and demands the Faith of those who lead them (vv.23-24).

The beginner goes through a life overhaul that "contorts" and "brings one to the ground".

This is because one can be plagued by dirigiste, unwise, covertly manipulative - despite being ineffective and underneath insecure - 'spiritual' guides.

Then it is a real heartbreak to discover that from childhood (v.21) we have been governed by a mortifying model - made up of easy classifications, which however do not realise, but dehumanise.

Perhaps we too have been conditioned by unwise directors.

And it was only through arduous, harrowing experiences that we discovered that precisely what we had been taught as sublime - and capable of assuring us communion with God - was, on the contrary, the primary cause of detachment from Him, and from a more harmonious and fuller personal and ecclesial existence.

In order to be liberated and rise to new life (v.27), the candidate of the path of Faith passes as if through a death - a sort of baptismal immersion, which drowns his old [de facto] paganising formation.

At the time of Mk many spoke of the expulsion of demons.

In the typology of the new baptism, the community of Rome wanted to express the goal of the Glad Tidings of the Gospels: to help people rise up - freeing themselves from the conditioning fears of evil.

That is not the real power.

In the passage, the child's deafness and muteness indicate the lack of the 'Word' that becomes an 'event' - unceasing, growing life, capable of transforming the marked, standard fate of 'earth'.

A lack that exists both among the bewildered people and - unfortunately - first and foremost among the disciples, sick of protagonism and one-sidedness.

The young man's very behaviour (vv.18.20.26) traces the existential modes of people subjugated by invincible forces, because they are self-destructive - therefore in the grip of obsessive, unrelenting lacerations.

Contrary to the quintessence of personal character.

It is a precisely heart-rending situation: that of those who discover they have been deceived by a religiosity of all-too-common convictions - with the epidermic, persuasive trick of herd or mass directions.

The coming of the Kingdom of God already meant the coming of an 'internal' power stronger than the Roman army itself, whose legions were used precisely to maintain situations of civil oppression, even religious fear.

Even today, a no-holds-barred struggle rages between the drives that induce deep-seated illnesses [like something that has taken hold of us] and the presence of the Messiah.

The two opposite poles cannot stand each other; they spark.

But the solution is not to amaze the crowds, nor is it to attempt to remake things that finally return to sacralising the status quo.

Thus, it sometimes seems that we are in no condition to initiate genuine healing processes (v.18b).

Yet evil does not give way by miracle and clamour, nor by man's force or insistence, but by attunement and Gift (v.29). From internal power-events.

Here is the space of prayer-listening.

Prayer brings one out of the confines and puts one in contact with other energies and surprises that one was not aware of: innate virtues and Grace, which allow one to see every situation with other, liberated eyes.

For solutions that solve real problems, from within, we constantly need not conformist rules, but a new reading.

Here is the dissymmetrical gaze.

Says the Tao Tê Ching (i): 'The Tao [way of conduct] that can be said is not the Eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the Eternal Name'. Master Wang Pi comments: 'An effable Tao indicates a practice.

Our life is not about the initiative of what we are already able to set up and practice - or interpret, design and predict (vv.14-19) - but about Attention (v.29).

The "mountain" to be moved [parallel v. Mt 17:20 - cf. Mt 19:20ff; Mk 10:20ff; Lk 18:21ff] is not outside, but within us.

In this way, the conformist idea that discourages us, or all obstacles (instead of harming us) will be precious opportunities for growth.

We will be at the centre of the reality of Incarnation.

To internalise and live the message:

How do you live your conflicts? What is your experience of healing?

Overcoming that "something of disbelief",

and "putting the flesh on the fire"

Miracles still exist today. But to enable the Lord to perform them there is a need for courageous prayer, capable of overcoming that "something of unbelief" that dwells in the heart of every man, even if he is a man of faith. A prayer especially for those who suffer from wars, persecutions and every other drama that shakes society today. But prayer must "put flesh on the fire", that is, involve our person and commit our whole life, to overcome unbelief [...].

Returning to the Gospel episode, the Holy Father reproposed the question of the disciples who had not been able to drive out the evil spirit from the young man: "But why could we not drive it out? This kind of demons, Jesus explained, cannot be driven out in any way except by prayer". And the boy's father "said: I believe Lord, help my unbelief". His was "a strong prayer; and this prayer, humble and strong, enables Jesus to perform the miracle. Prayer to ask for an extraordinary action,' the Pontiff explained, 'must be a prayer that involves all of us, as if we were committing our whole life to it. In prayer we must put meat on the fire'.

The Pontiff then recounted an episode that happened in Argentina: "I remember something that happened three years ago in the sanctuary of Luján. A seven-year-old girl had fallen ill, but the doctors could not find a solution. She was getting worse and worse, until one evening, the doctors said there was nothing more they could do and that she only had a few hours to live. "The father, who was an electrician, a man of faith, became like mad. And driven by that madness he took the bus and went to the sanctuary of Luján, two and a half hours by bus, seventy kilometres away. He arrived at nine in the evening and found everything closed. And he began to pray with his hands clinging to the iron gate. He was praying and crying. So he stayed the whole night. This man was fighting with God. He was really struggling with God for the healing of his maiden. Then at six in the morning he went to the terminal and took the bus. He arrived at the hospital at nine o'clock, more or less. He found his wife crying and thought the worst: what happened? I don't understand. What happened? The doctors came, his wife told him, and they said the fever is gone, she's breathing well, there's nothing.... They will only keep her another two days. But they don't understand what has happened. And this,' the Pope commented, 'still happens. There are miracles. But prayer is needed! A courageous prayer, one that struggles to reach that miracle, not those prayers out of courtesy: Ah, I will pray for you! Then a Pater Noster, an Ave Maria and I forget. No! It takes courageous prayer, like that of Abraham who wrestled with the Lord to save the city; like that of Moses who prayed with his hands up and tired praying to the Lord; like that of so many people who have faith and with faith pray, pray".

Prayer works miracles, "but," Pope Francis concluded, "we must believe it. I think we can make a beautiful prayer, not a prayer out of courtesy, but a prayer with the heart, and say to Him today throughout the day: I believe Lord! Help my unbelief. We all have unbelief in our hearts. Let us say to the Lord: I believe, I believe! You can! Help my unbelief. And when we are asked to pray for so many people who suffer in wars, in their plight as refugees, in all these dramas we pray, but with our hearts, and we say: Lord, do. I believe, Lord. But help my unbelief".

[Pope Francis, St. Martha, in L'Osservatore Romano 20-21/05/2013].

The Mount. Structure of Christian Life

Today, the Second Sunday of Lent, as we continue on the penitential journey, the liturgy invites us, after presenting the Gospel of Jesus' temptations in the desert last week, to reflect on the extraordinary event of the Transfiguration on the mountain. Considered together, these episodes anticipate the Paschal Mystery: Jesus' struggle with the tempter preludes the great final duel of the Passion, while the light of his transfigured Body anticipates the glory of the Resurrection. On the one hand, we see Jesus, fully man, sharing with us even temptation; on the other, we contemplate him as the Son of God who divinizes our humanity. Thus, we could say that these two Sundays serve as pillars on which to build the entire structure of Lent until Easter, and indeed, the entire structure of Christian life, which consists essentially in paschal dynamism: from death to life.

The mountain - Mount Tabor, like Sinai - is the place of nearness to God. Compared with daily life it is the lofty space in which to breathe the pure air of creation. It is the place of prayer in which to stand in the Lord's presence like Moses and Elijah, who appeared beside the transfigured Jesus and spoke to him of the "exodus" that awaited him in Jerusalem, that is, his Pasch. The Transfiguration is a prayer event: in praying, Jesus is immersed in God, closely united to him, adhering with his own human will to the loving will of the Father, and thus light invades him and appears visibly as the truth of his being: he is God, Light of Light. Even Jesus' raiment becomes dazzling white. This is reminiscent of the white garment worn by neophytes. Those who are reborn in Baptism are clothed in light, anticipating heavenly existence (cf. Rev 7: 9, 13). This is the crucial point: the Transfiguration is an anticipation of the Resurrection, but this presupposes death. Jesus expresses his glory to the Apostles so that they may have the strength to face the scandal of the Cross and understand that it is necessary to pass through many tribulations in order to reach the Kingdom of God. The Father's voice, which resounds from on high, proclaims Jesus his beloved Son as he did at the Baptism in the Jordan, adding: "Listen to him" (Mt 17: 5). To enter eternal life requires listening to Jesus, following him on the way of the Cross, carrying in our heart like him the hope of the Resurrection. "Spe salvi", saved in hope. Today we can say: "Transfigured in hope".

Turning now in prayer to Mary, let us recognize in her the human creature transfigured within by Christ's grace and entrust ourselves to her guidance, to walk joyfully on our path through Lent.

[Pope Benedict, Angelus, 17 February 2008]

This is also the Way of his intimates

The mystery of the Transfiguration takes place at a very precise moment in Christ's preaching of his mission, when he begins to confide to his disciples that he must "go up to Jerusalem and suffer much ... and be killed and rise again on the third day" (Mt 16:21). With reluctance they accept the first announcement of the passion and the divine Master, before repeating and confirming it, wants to give them proof of his total rootedness in the will of the Father so that before the scandal of the cross they will not succumb. The passion and death will in fact be the way by which the heavenly Father will lead "the beloved Son", raised from the dead, to glory. This will henceforth also be the way of his disciples. No one will come to the light except through the cross, symbol of the sufferings that afflict human existence. The cross is thus transformed into an instrument of atonement for the sins of all humanity. United with his Lord in love, the disciple participates in his redemptive passion.

[Pope John Paul II, homily 7 March 1993]

For the gift

The Gospel of this second Sunday of Lent (cf. Mt 17:1-9), presents to us the account of the Transfiguration of Jesus. He takes Peter, James and John with him up a high mountain, symbol of closeness to God, to open them to a fuller understanding of the mystery of his Person, that must suffer, die and then rise again. Indeed, Jesus had begun to speak to them of the suffering, death and Resurrection that awaited him, but they were unable to accept this prospect. Therefore, once they reached the summit of the mountain, Jesus immersed himself in prayer and was transfigured before the three disciples: “his face”, says the Gospel, “shone like the sun, and his clothes became white as light” (v. 2).

Through the wondrous event of the Transfiguration, the three disciples are called to recognize in Jesus the Son of God shining with glory. Thus, they advance in their knowledge of their Master, realizing that the human aspect does not express all his reality; in their eyes the otherworldly and divine dimension of Jesus is revealed. And from on High there resounds a voice that says: “This is my beloved Son.... Listen to him” (v. 5). It is the heavenly Father who confirms the “investiture” — let us call it that — that Jesus already received on the day of his Baptism in the Jordan and invites the disciples to listen to him and to follow him.

It must be emphasized that, from among the group of the Twelve, Jesus chose to take James, John and Peter with him up the mountain. He reserved for them the privilege of witnessing the Transfiguration. But why did he select these three? Because they are the holiest? No. Yet, at the hour of trial, Peter will deny him; and the two brothers James and John will ask for the foremost places in his Kingdom (cf. Mt 20:20-23). However Jesus does not choose according to our criteria, but according to his plan of love. Jesus’ love is without measure: it is love, and he chooses with that plan of love. It is a free, unconditional choice, a free initiative, a divine friendship that asks for nothing in return. And just as he called those three disciples, so today too he calls some to be close to him, to be able to bear witness. To be witnesses to Jesus is a gift we have not deserved; we may feel inadequate but we cannot back out with the excuse of our incapacity.

We have not been on Mount Tabor, we have not seen with our own eyes the face of Jesus shining like the sun. However, we too were given the Word of Salvation, faith was given to us, and we have experienced the joy of meeting Jesus in different ways. Jesus also says to us: “Rise, and have no fear” (Mt 17:7). In this world, marked by selfishness and greed, the light of God is obscured by the worries of everyday life. We often say: I do not have time to pray, I am unable to carry out a service in the parish, to respond to the requests of others.... But we must not forget that the Baptism and Confirmation we have received has made us witnesses, not because of our ability, but as a result of the gift of the Spirit.

In the favourable time of Lent, may the Virgin Mary obtain for us that docility to the Spirit which is indispensable for setting out resolutely on the path of conversion.

[Pope Francis, Angelus, 8 March 2020]

Perfection: going all the way. And new Birth

Between intimate struggle and not opposing the evil one

(Mt 5:43-48)

Jesus proclaims that our heart is not made for closed horizons, where incompatibilities are accentuated.

He forbids exclusions, and with it resentments, communication difficulties.

In us there is something more than every facet of opportunism, and instinct to retort blow by blow... to even the score... or close oneself in one's own exemplary group.

In Latin perfĭcĕre means to complete, to lead to perfection, to do completely.

We understand: here it’s essential to introduce other energies; letting mysterious virtues act... between the deepest spaces that belong to us, and the mystery of events.

Otherwise we would assimilate an external integrity model, which doesn’t flow from the Source of being and doesn’t correspond to us in essence.

Within the paradigms of perfection, the captive Uniqueness would no longer know where to go.

Diamonds seem perfect - but nothing is born of them: God's ‘perfect’ ones are those who go ‘all the way’.

Jesus doesn’t want the existence of Faith to be marked by the usual hard extrinsic struggle - made up of intimate lacerations.

There are differences; however He orders to subvert the customs of ancient wisdom and divisions (acceptable or not, friend or foe, near or far, pure and impure, sacred and profane).

The Kingdom of God, that is the community of sons - this sprout of an alternative society - is radically different because it starts from the Seed, not from external gestures; nor does it use sweeteners, to conceal the intimate confrontation.

Events spontaneously regenerate, outside and even within us; useless to force.

The growth and destination continues and will become magnificent, also thanks to the mockery and constraints set up in an adverse way.

Surrendering, giving in, putting down the armor, will make room for new joys.

Fighting what appear to be “adversaries” confuses the soul: it is precisely the stumbles on the intended path that open up and ignite the living space - normally too narrow, suffocated by obligations.

Subtle awareness and perfection that distinguishes the authentic new man in the Spirit from the barker who ignores the things of the Father and seeks laboured shortcuts, by passing favours and 'bribes' in order to immediately settle his business with God and neighbour.

Loving the enemy who [draws us out and] makes us Perfect:

If others are not as we have dreamed of, it’s fortunate: the doors slammed in the face and their goad are preparing us many other joys.

The adventure of extreme Faith is for a wounding Beauty and an abnormal, prominent Happiness.

The ‘win-or-lose’ alternative is false: one must get out of it.

Here, only those who know to wait will find their Way.

To internalize and live the message:

What awareness or purpose do you propose in involving time, perception, listening, kindness? Appear different from your disposition, to please others? Get accepted? Or become perfectly yourself, and wait for the developments that are brewing?

[Saturday 1st wk. in Lent, February 28, 2026]

Perfection: going all the way. And new Birth

Between intimate struggle and not opposing the evil one

(Mt 5:43-48)

In his first encyclical Pope Benedict wrote:

"With the centrality of love, the Christian faith has taken up what was the core of the faith of Israel and at the same time has given this core a new depth and breadth. The believing Israelite, in fact, prays every day with the words of the Book of Deuteronomy, in which he knows that the centre of his existence is enclosed: Listen, Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength' (6:4-5). Jesus united the commandment of love of God with the commandment of love of neighbour, contained in the Book of Leviticus: "You shall love your neighbour as yourself" (19:18; cf. Mk 12:29-31), making it a single precept. Since God loved us first (cf. 1 John 4:10), love is now no longer just a "commandment", but is the response to the gift of love, with which God comes to us.

In a world where the name of God is sometimes linked to vengeance or even the duty of hatred and violence, this is a message of great relevance and very concrete meaning" [Deus Caritas est, n.1].

The "victory-or-defeat" alternative is false: we must come out of it

Jesus proclaims that our heart is not made for closed horizons, where incompatibilities are accentuated.

He forbids exclusion, and with it resentments, difficulties in communication.

There is something more in us than any facet of opportunism, and the instinct to strike back blow after blow... to even the score... even to close oneself within one's own exemplary group.

In Latin perfĭcĕre means to fulfil, to complete, to lead to perfection, to do completely.

We understand it: here it is indispensable to introduce other energies; to let mysterious virtues act... between the deepest spaces that belong to us, and the mystery of events.

How for us to reach the summit of the Mount of the Beatitudes. For a new Birth, a new Beginning.

Impossible, if we do not allow an innate, primordial Wisdom to develop - magmatic, yet far more intact and inapposite.

Venturing away from one's enclosure - even out of the worldly chorus - may not make one original, but it does begin to cure our eccentric exceptionalism.

Otherwise we would assimilate an external model of integrity, which does not spring from the Source of being and does not correspond to us in essence.

Within the paradigms of perfection, the captive uniqueness would no longer know where to go. It would go round in circles believing it would climb [in religion, as on a spiral staircase, which leads to nothing: a typical mechanism of ascetic forms].

In the exasperation of models outside ourselves, we subject the soul to the style of (even ecclesiastical) celebrities.

The anxiety produced by the narrowness of charisma, of champions, of roles lacking deep harmony, will then be ready to attack us; it will present itself around the corner as an invincible adversary.

Perfect seem like diamonds - from which, however, nothing is born: God's perfect are those who go all the way.

The Tao says: 'If you want to be given everything, give up everything'.

"Everything" also means the image we are accustomed to present to others, to be liked at any cost. One has to come out of it.

A transgressive Jesus meets the Wisdom of all times, even the natural one - absolutely not conformist.

He does not want the existence of Faith to be marked by the usual hard extrinsic struggle [typical of the 'spiritual' mentality] made of intimate lacerations.

Even today - unfortunately - in many believing realities, one is still trained in the idea of the inevitable opposition between instincts to life and decent standards.

The Lord glosses over the addictive idea of devout toil, and does so by daring to supplement the ancient Scripture, almost correcting the roots of the civil and venerable identity of the people, identified in the Torah.

Several times and in succession he suggests modifying the sacred and unappealable treasure of the Law: 'It was said [...] Now I say to you'.

The differences are there, yet Jesus commands to subvert the customs of ancient wisdom, the divisions involved: acceptable or not, friends or foes, near or far, pure and impure, sacred and profane; so on.

The Kingdom of God, that is, the community of children - this offshoot of an alternative society - is radically different because it starts from the Seed, not from outward gestures; nor does it use sweeteners, to conceal the intimate clash.

It is not 'new' as the latest of wiles or inventions to be set up.... But because it supplants the whole world of one-sided artifices.

In this way: souls must take the pace of things, to grasp the very rhythm of God, who wisely creates.

Events regenerate spontaneously, outside and even within us; it is useless to force them.

The growth and destination remains and will become magnificent, even through the mockery and constraints set up against it - by the most blatant and insincere exhibitionists, or by those who seem close.

Surrendering, giving in, laying down the armour, will make room for new joys.

Fighting the 'allergists' confuses the soul: it is precisely the stumbling on the intended path that opens and ignites the vital space - normally too narrow, suffocated by obligations.

In the Tao Tê Ching we read: 'If you want to obtain something, you must first allow it to be given to others'.

The blossoming will follow the natural nature of the children: it will be without any effort or recitation of volitional, overburdened holiness (sympathetic or otherwise).

Subtle awareness and Perfection that distinguishes the authentic new man in the Spirit from the barker who ignores the things of the Father and seeks laboured shortcuts, passing favours and 'bribes' in order to immediately settle his affairs with God and neighbour.

Love the enemy who [draws us out and] makes us Perfect:

If others are not as we dreamed, it is fortunate: the doors slammed in our faces and their stinging are preparing other joys for us.

The adventure of extreme Faith is for a Beauty that wounds and an abnormal, prominent Happiness.

Here, only those who know how to wait find their Way.

To internalise and live the message:

What awareness or purpose do you set yourself in engaging time, perception, listening, kindness?

To appear different from your nature, to please others? To make yourself accepted?

Or be perfectly yourself, and wait for the developments that are brewing?

New beginning

“You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy”, we read in the Book of Leviticus (19:1). With these words and with the consequent precepts the Lord invited the People whom he had chosen to be faithful to the Covenant with him, to walk on his path; and he founded social legislation on the commandment “you shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Lev 19:18).

Then if we listen to Jesus in whom God took a mortal body to make himself close to every human being and reveal his infinite love for us, we find that same call, that same audacious objective. Indeed, the Lord says: “You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48).

But who could become perfect? Our perfection is living humbly as children of God, doing his will in practice. St Cyprian wrote: “that the godly discipline might respond to God, the Father, that in the honour and praise of living, God may be glorified in man (De zelo et livore [On jealousy and envy], 15: CCL 3a, 83).

How can we imitate Jesus? He said: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in Heaven” (Mt 5:44-45). Anyone who welcomes the Lord into his life and loves him with all his heart is capable of a new beginning. He succeeds in doing God’s will: to bring about a new form of existence enlivened by love and destined for eternity.

The Apostle Paul added: “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” (I Cor 3:16). If we are truly aware of this reality and our life is profoundly shaped by it, then our witness becomes clear, eloquent and effective. A medieval author wrote: “When the whole of man’s being is, so to speak, mingled with God’s love, the splendour of his soul is also reflected in his external aspect” (John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, XXX: PG 88, 1157 B), in the totality of life.

“Love is an excellent thing”, we read in the book the Imitation of Christ. “It makes every difficulty easy, and bears all wrongs with equanimity…. Love tends upward; it will not be held down by anything low… love is born of God and cannot rest except in God” (III, V, 3).

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 20 February 2011]

Path of Lent, learning a little more how to “ascend” with prayer and listen to Jesus and to “descend” with brotherly love, proclaiming Jesus (Pope Francis)

Itinerario della Quaresima, imparando un po’ di più a “salire” con la preghiera e ascoltare Gesù e a “scendere” con la carità fraterna, annunciando Gesù (Papa Francesco)

Anyone who welcomes the Lord into his life and loves him with all his heart is capable of a new beginning. He succeeds in doing God’s will: to bring about a new form of existence enlivened by love and destined for eternity (Pope Benedict)

Chi accoglie il Signore nella propria vita e lo ama con tutto il cuore è capace di un nuovo inizio. Riesce a compiere la volontà di Dio: realizzare una nuova forma di esistenza animata dall’amore e destinata all’eternità (Papa Benedetto)

You ought not, however, to be satisfied merely with knocking and seeking: to understand the things of God, what is absolutely necessary is oratio. For this reason, the Saviour told us not only: ‘Seek and you will find’, and ‘Knock and it shall be opened to you’, but also added, ‘Ask and you shall receive’ [Verbum Domini n.86; cit. Origen, Letter to Gregory]

Non ti devi però accontentare di bussare e di cercare: per comprendere le cose di Dio ti è assolutamente necessaria l’oratio. Proprio per esortarci ad essa il Salvatore ci ha detto non soltanto: “Cercate e troverete”, e “Bussate e vi sarà aperto”, ma ha aggiunto: “Chiedete e riceverete” [Verbum Domini n.86; cit. Origene, Lettera a Gregorio]

In the crucified Jesus, a kind of transformation and concentration of the signs occurs: he himself is the “sign of God” (John Paul II)

In Gesù crocifisso avviene come una trasformazione e concentrazione dei segni: è Lui stesso il "segno di Dio" (Giovanni Paolo II)

Only through Christ can we converse with God the Father as children, otherwise it is not possible, but in communion with the Son we can also say, as he did, “Abba”. In communion with Christ we can know God as our true Father. For this reason Christian prayer consists in looking constantly at Christ and in an ever new way, speaking to him, being with him in silence, listening to him, acting and suffering with him (Pope Benedict)

Solo in Cristo possiamo dialogare con Dio Padre come figli, altrimenti non è possibile, ma in comunione col Figlio possiamo anche dire noi come ha detto Lui: «Abbà». In comunione con Cristo possiamo conoscere Dio come Padre vero. Per questo la preghiera cristiana consiste nel guardare costantemente e in maniera sempre nuova a Cristo, parlare con Lui, stare in silenzio con Lui, ascoltarlo, agire e soffrire con Lui (Papa Benedetto)

In today’s Gospel passage, Jesus identifies himself not only with the king-shepherd, but also with the lost sheep, we can speak of a “double identity”: the king-shepherd, Jesus identifies also with the sheep: that is, with the least and most needy of his brothers and sisters […] And let us return home only with this phrase: “I was present there. Thank you!”. Or: “You forgot about me” (Pope Francis)

Nella pagina evangelica di oggi, Gesù si identifica non solo col re-pastore, ma anche con le pecore perdute. Potremmo parlare come di una “doppia identità”: il re-pastore, Gesù, si identifica anche con le pecore, cioè con i fratelli più piccoli e bisognosi […] E torniamo a casa soltanto con questa frase: “Io ero presente lì. Grazie!” oppure: “Ti sei scordato di me” (Papa Francesco)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.