Argentino Quintavalle

Argentino Quintavalle è studioso biblico ed esperto in Protestantesimo e Giudaismo. Autore del libro “Apocalisse - commento esegetico” (disponibile su Amazon) e specializzato in catechesi per protestanti che desiderano tornare nella Chiesa Cattolica.

Second Lent Sunday (year A) [Mt 17:1-9]

Matthew 17:3 And behold, Moses and Elijah appeared to them, conversing with him.

Matthew 17:4 Then Peter spoke up and said to Jesus, 'Lord, it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will make three tents here, one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.'

Matthew 17:5 While he was still speaking, a bright cloud overshadowed them, and behold, a voice from the cloud said, 'This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.'

Matthew 17:6 When the disciples heard this, they fell on their faces and were very much afraid.

Matthew 17:7 But Jesus came and touched them, saying, 'Get up and do not be afraid.

Matthew 17:8 When they looked up, they saw no one but Jesus alone.

Matthew 17:9 As they were coming down the mountain, Jesus commanded them, "Tell no one about this vision until the Son of Man has been raised from the dead."

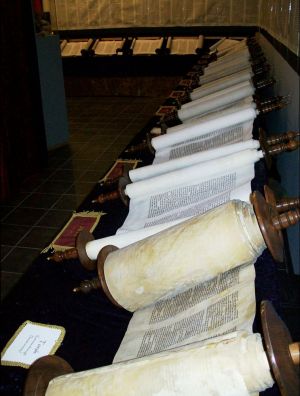

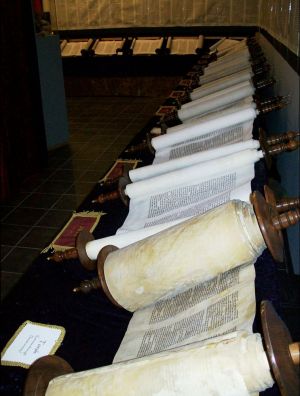

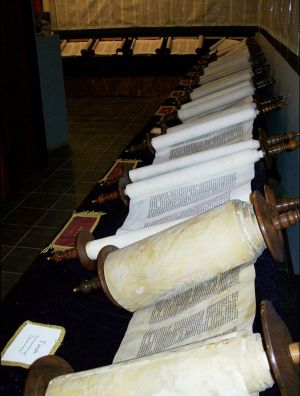

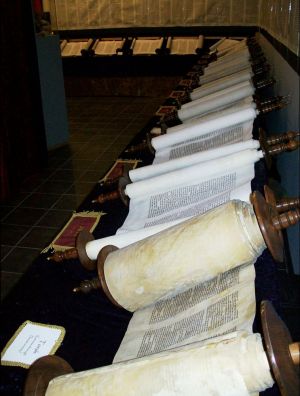

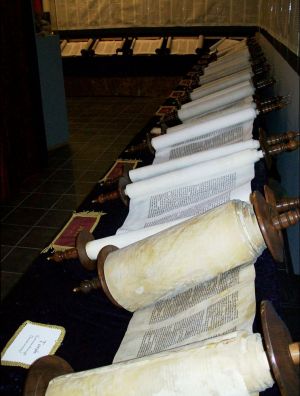

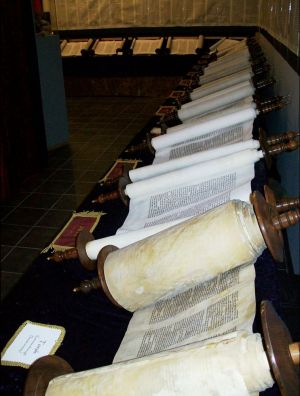

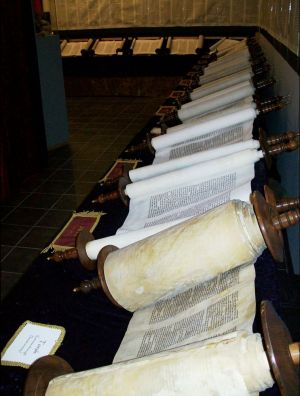

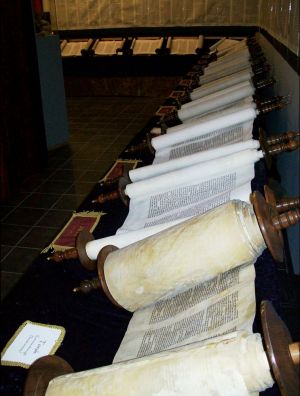

Next to Jesus, transfigured and shining with the same light as God, two Old Testament figures of great importance suddenly and unexpectedly appear: Moses and Elijah. The first is the one God chose to free his people from oppression in Egypt and lead them to the land promised to the Patriarchs. Moses is the one who spoke with God face to face, revealing the familiarity that existed between the two. Moses is the one who received the Torah directly from God and revealed it to the people. He was an intercessor, the intermediary of the covenant between God and Israel. Elijah, on the other hand, was the one who opposed the betrayals of the people and their rulers and, defying the wrath of Queen Jezebel and the claims of the priests of Baal, sought to assert God's lordship among the people, putting his own life at risk.

The presence of these characters is also due to the fact that Jesus said in chapter 5 of the Gospel: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets", that is, Jesus did not come to destroy the promises of the Old Testament, contained in the law and the prophets, but to bring them to fulfilment, to completeness. With their presence, Moses and Elijah bear witness to Jesus and show that He is the end to which both the law and the prophets were ordained. These are also the two figures who spoke with God in the Old Testament. Just as Moses and Elijah spoke with God, now they speak with Jesus and him alone. It is not said that Jesus speaks with them, but that they speak with Jesus; it is they who converge on Jesus and not vice versa. There is, therefore, no dialogue. Elijah and Moses, the whole revelation given by God to the fathers, speak with Jesus.

The scene is charged with symbolism and meaning. Matthew included it to convey the new significance of the figure of Jesus in relation to the symbolic figures of the Old Testament. Jesus is not an addition to Moses and Elijah, he is not an extension of them, but their point of convergence. In a certain sense, they define the meaning of his mission and his being: like Moses, Jesus was sent to Israel and to all humanity to free it from the slavery of sin and lead it back to the Father. At the same time, he also acts as a mediator between God and men, a sort of pontiff, connecting humanity to God in a secure and definitive covenant between God and men that will never fail. Similar to Elijah, the prophet who spent his life and put it at risk to reaffirm the worship of God among his people, Jesus also came to restore the Father's will among men, to reveal its demands and to urge them to return to God. Moses and Elijah, therefore, were paradigmatic, typical figures who foreshadowed in themselves the essential traits of the figure of Jesus, in whom they converge and find their fulfilment.

Verse 4 denounces an error of perspective into which Judeo-Christianity will fall: considering Jesus a great figure, a prominent prophet, an important messiah, but one who did not differ from his Old Testament predecessors, represented by Moses and Elijah, but rather was linked to them. Peter, in fact, has Jesus, Moses and Elijah before him and, without any distinction, proposes three tents for them, one for each of them, all three on an equal footing. It is as if Peter, and with him Jewish Christianity, still could not grasp the novelty contained in the mystery of Jesus, whom he places on the same level as Moses and Elijah and associates with them.

With verse 5, we reach the heart of the story, which aims to emphasise Jesus' divine sonship and, therefore, his own divinity. The revelation reaches its climax here, as God himself is now involved in the matter, his presence evoked by two theophanic elements: the cloud and the voice. The first closely recalls the 'shekinah', the glorious presence of Yahweh, while the second is linked to the first and indicates the revelation of God.

The brightness of the cloud contrasts with the verb epeskíasen, 'overshadowed', 'darkened'. It is astonishing how a cloud glowing with divine light can darken and overshadow. In reality, this play on words speaks of revelation and new understanding. What this cloud obscures, in fact, are Jesus, Moses and Elijah, whom Peter had placed on an equal footing, without noting their substantial difference. It is this error, which redefines Jesus along the lines of the Old Testament, bringing him back into it, that is, so to speak, overshadowed, hidden; while within the divine light, the true mystery underlying the person of Jesus is revealed.

The Church has nothing more to take from Moses or Elijah, except those parts that are compatible with the message of Jesus. The evangelist does not say that the Old Testament should be discarded, but that Jesus becomes the norm for interpreting the Old Testament. This is a warning that is more relevant than ever, because there have always been groups that are tempted to emphasise certain norms of the Old Testament and integrate them into the Christian community.

The passage ends (v. 9) with the disciples returning to normal daily life: they come down from the mountain, and it is during this return that Jesus orders them to remain silent about the vision. He forbids them to speak of it before the resurrection, because only then will they understand what the transfiguration is: it is a foretaste of the resurrection. In the meantime, they will allow the mystery they have intuited to mature within them.

It is therefore necessary to wait for the appointed time for Jesus to be understood in his entirety, and this time will only come after Jesus has been glorified ('risen from the dead'). Only then will the meaning of his being, his divinity and his messiahship become clear. Only then will the Scriptures be understood and acquire new meaning; only then, in the Risen One, will the Law and the Prophets find their fulfilment. The mystery must now be shrouded in the silence of an imperfect understanding, which can be intuited but not yet fully grasped. While waiting for the mystery to be fulfilled, silence is necessary so that the mystery is not trivialised or rejected.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All Generations Will Call Me Blessed

Catholics and Protestants Compared – In Defence of the Faith

The Church and Israel According to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

First Sunday in Lent (Year A)

(Mt 4:1-1)

Matthew 4:1 Then Jesus was led by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.

Matthew 4:2 After fasting forty days and forty nights, he was hungry.

Matthew 4:3 The tempter came to him and said, 'If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become bread.'

Matthew 4:4 But he answered, 'It is written:

Man shall not live by bread alone,

but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.'

Jesus is led by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. One may wonder, why would the Spirit lead someone into a dangerous situation? There is no doubt here that it is the Holy Spirit who pushes Jesus to confront the devil, and thus all the false expectations of the time regarding the figure of the Messiah, which we now understand were diabolical expectations.

The Greek term for temptation is 'peirazō', which mainly means 'to test, to examine', but also 'to tempt' in the moral sense of soliciting evil. The verb can be translated as both testing and tempting. When it is God who performs the action, then we have the sense of testing, because it is something that serves the growth and maturity of the person, so that the person can make a serious assessment of their own life. It is something positive. Even in the Gospels we find that Jesus sometimes tests his disciples to see if they have understood his teachings. When, on the other hand, this verb has Satan as its subject, then we are talking about tempting, about putting the person in a dangerous situation in order to distract them from their duty. In our text, the devil tries to distract Jesus from his messianic task.

'Devil' in Greek means divider, separator, and its Hebrew equivalent, 'satan', means 'adversary'. He is the enemy and adversary of man, who wants to hinder Jesus and also every man on his journey with God. It is like saying: I want to continue on this path, but at a certain point the path is blocked; this is Satan, the devil, someone who wants to lead me astray.

Jesus was led into the desert, west of Jericho, on the Mount of Quarantine. But it is not the geographical location that is important here. The desert represents the place of trial. It is the place where the people of Israel could demonstrate their fidelity to God, or their infidelity; it was the place where man had to verify his choices. It is the place where we can discover the truth, because the real struggle is not so much against someone else, but within ourselves. We can say that the desert is an existential situation for everyone. We find truth only in the desert, because as long as there is someone close to us, we can always say: it was him, it's his fault. But if we are alone, we can only see the evils that are within us. So we need to know how to create the desert, the silence, to go into the truth and not be afraid of the truth. The desert is the place of searching, of journeying, and it is here that we find the devil, that is, the divider, the split, we find evil. This is precisely where the Spirit leads us! We think that the spiritual life is something privileged, but it is exactly the opposite, it leads us into reality, it leads us into temptation, into trial, into doubt, into the difficulty of discerning, of deciding, into struggle.

The verb peiraō (to tempt) also means 'to learn from experience', 'to experience', 'to try', so it is through temptation that man passes through evil, and thus becomes experienced, gains experience. And temptation is suffered by those who have made the right choice. If someone is stealing and is tempted to stop, that is not called temptation, but good inspiration! So we must consider trial and temptation as a place where, if one chooses good, one encounters evil. That is why it is the Spirit who drives us into the desert, that is, it is the Spirit of God himself who drives me to make a choice, to seek clarity, to seek truth.

At the end of forty days and forty nights, Jesus is hungry. This hunger should be interpreted as a state of need. The devil always uses every need to tempt man. Even in families, it is much easier to argue when there are needs than when things are going well, precisely because the devil has the opportunity to get in the way.

"The tempter then approached him." Here the name is changed; we are not talking about the devil but about the tempter. It is an expression used only by Matthew, because the verb "to tempt" is the typical verb that the evangelist will use when speaking of the Pharisees, the high priests and the Sadducees when they go to Jesus to tempt him. They are the ones who carry out the temptations of Jesus. For this reason, the evangelist changes the name and presents Satan as the tempter, to remind us that it will be others acting on behalf of the devil who will tempt Jesus.

The first temptation begins with the proposal: if you are the Son of God, say that these stones become bread. The temptation can be read in different ways: Take advantage of your position for your own good, make these stones satisfy your hunger. If you can do it, do it.

With the necessary exceptions, all temptations are always for the good. None of us does evil because it is evil, but because it seems good to us. Except for those few times - or many times - when we do it out of weakness, when we know it is evil but cannot do otherwise, the serious mistakes are those we make for the good. May God free us from the evil we can do thinking it is good! They are like the just wars of Anglo-Zionist memory: they never end, precisely because they are just! So we must be careful when we act for the sake of good: it is very dangerous! We must not act for the sake of good, we must do what is good. We can be diabolical for the sake of good!

Another interpretation of the temptation is as follows: Jesus is urged to use his authority as the Son of God to bring about a turning point in the history of his people or, if you will, to listen to the messianic expectations of Israel, which was awaiting a political-military and religious messiah, a liberator and restorer of Israel's greatness. From this perspective, the first temptation is that of economic messianism: that is, to think of bringing about the messianic era through earthly economic well-being. In other words, Jesus is tempted to turn stones into bread in order to perform a prodigious act in the eyes of humanity: if he is the Son of God, he will be able to solve the problem of world hunger and be recognised and acclaimed as a benefactor. Fyodor Dostoevsky's reinterpretation of this temptation in "The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor" is very interesting: "Do you see these stones in the bare, scorched desert? Turn them into bread, and humanity will follow you like a docile and grateful flock."

The first temptation can also be read as a false alternative: either bread or the word. While we say: yes, the word of God is beautiful, but now there is real life, I have to think about this and that. This is a great evil, because if the word of God has nothing to do with real life, God does not exist. In reality, the first thing is the word of God that orders my way of relating to things, and therefore my real life, my bread. In response to the tempter, Jesus reminds him that it is in fidelity to the word of God that man can find the true meaning of his existence.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

6th Sunday in Ordinary Time (year A)

(Mt 5:17-37)

Matthew 5:19 Whoever breaks one of these least commandments and teaches others to do so will be called least in the kingdom of heaven. But whoever practises and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven.

This verse presents a parallelism characteristic of the Hebrew rhetorical style, which here contrasts transgression with observance, the least with the greatest, or, if you will, the relative with the whole, highlighting how the smallest of the commandments can make those who do not observe it small, thus demonstrating the great spiritual power of a commandment considered small by human sophistry, but nevertheless great because it reflects and expresses the will of God, which must always be carried out.

Note how this sentence of Jesus unfolds in two moments which, although radically opposed to each other, nevertheless find their common point of reconnection in the verb 'to teach'. To be minimal or great, it is not enough to 'transgress' or 'observe', but there must also be teaching. It is, therefore, the way of behaving and relating within the community, understood here as the place of the kingdom of heaven, that makes one small or great within it.

A simple personal violation of the commandment is not enough to be degraded, but it must also be accompanied by teaching in that sense. Personal violation in itself does not seem to be serious enough to condemn the person ipso facto, perhaps because such violation is considered the result of human weakness; but when the error is transmitted through specific teaching, then it becomes ingrained and there is a clear desire to spread it, which therefore becomes a stumbling block for others. Similarly, scrupulously observing the commandments in one's private life is of no benefit if it is not accompanied by public witness, for the lamp must always be placed on the candlestick so that it may give light to all those in the house.

In Israel, in fact, observance or violation of the Law was never considered a private matter, even though it personally engaged every single Israelite in its practice. The Sinaitic covenant was a covenant made with the people, and its violation was always understood primarily as a collective fault, which was always followed by collective punishment. Evidence of this can be found in the Babylonian exile and, even earlier, in the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians. Throughout the history of Israel, God never speaks to individuals, but only to the people or their legitimate representatives. For this reason, teaching is what qualifies violation or observance, establishing the respective position of each member within the kingdom of heaven, of which the new community is a sacrament.

What are the minimum commandments? There is some confusion about this. Are they all the precepts of the Law? But if we look at what the evangelists have handed down to us about Jesus, we see, for example, that Jesus did not observe the laws of purity concerning lepers (he touched them). When Jesus speaks of repudiation, he speaks differently from Moses; he saves an adulteress from stoning. On some occasions, he did not observe the most important law, that of the Sabbath, at least according to the Pharisaic interpretation, and so on.

We must therefore understand Jesus' words bearing in mind that these minimal commandments are none other than those he has just proclaimed from the Mount through the image of the Beatitudes. Why are they considered minimal? Why this expression? It is what Jesus will declare to those who want to follow him: "My yoke is easy and my burden is not heavy". In this sense, we can interpret the minimal commandments. It is true that putting the message into practice involves commitments, and that these commitments are often demanding, but they are never crushing commitments, as the Law was for all those who tried to put it into practice.

Jesus, speaking of the Beatitudes as the minimum commandments, is telling us that although observance involves a commitment, it is not a commitment that cannot be carried out, like a kind of yoke placed on the neck that prevents one from walking. Those in the community who betray the message – the commandments of the Beatitudes – and teach others to do the same will be considered the least in the kingdom of heaven; but those who practise and teach them will be considered great.

The two categories, the contrast between least and greatest, do not refer to a hierarchy, as if there were first- and second-class Christians in the kingdom or community. Rather, it is a way of speaking according to Semitic language: to be least means to be excluded from a reality; to be greatest means to be part of that reality. Jesus says that those who betray the spirit of the Beatitudes, those who do not live according to this teaching, had better give up; they cannot feel part of the community of the kingdom, they exclude themselves. On the contrary, full participation in the kingdom belongs to those who will put it into practice and teach others to do so.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

5th Sunday in Ordinary Time (year A)

(Mt 5:13-16)

Matthew 5:15 Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bushel, but on a lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house.

Matthew 5:16 In the same way, let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven.

Jesus says: when you light a lamp, you cannot put it under a container, that would be absurd, but you place it on a candlestick so that it can give light to all those in the house. This is the task of the disciples, who by putting the message of the Beatitudes into practice can render a vital service to the world. Believers are defined as light and lamps. The meaning is identical, since the lamp has to do with light that illuminates, but their illumination is different. As light, the community is in reference to the world and must make itself visible among men like a city set on a hill; while individual believers, defined in their intra-community relationships, are called to be lamps for 'all those in the house'.

The light, therefore, must shine both inside and outside the community. The light that illuminates men must start from within the community and then radiate out to everyone. It is a light that flows from the very heart of every believer, rooted in the risen Christ, which permeates the entire community and then spreads out into the world. Only if every single believer shines with the light of the Risen One will the community be illuminated and become a light for the world. Light does not change reality; light makes reality visible.

In fact, the immediate consequence of light is precisely seeing: "so that they may see" (v. 16), that is, noticing something new that has been born among men - God's very action among them - which they must see through "your good works". These good works of the believer closely recall the refrain of creation: "And God saw that it was good" . The good works accomplished by the believer are parallel to God's creation. It is significant that God's creative act begins precisely with light (Gen 1:3), and in this context of light, the entire creation is then placed. Thus, the accomplishment of good works by the disciple becomes the new dimension into which humanity is called to enter. Indeed, it is precisely these good works that become the cause of a new humanity that praises God: "glorify your Father who is in heaven." Giving glory is a somewhat abstract expression. To explain it simply, we can say: love translated into works. When people want to give glory to God, all they have to do is translate the love they experience into concrete gestures towards others. The purpose of these works is that people may recognise God, and feeling loved, may discover in their own lives that there is a God who is Father, who manifests this love.

The verb 'doxazō', translated as 'give glory', will later be presented by Jesus when speaking to the Pharisees who want 'to be praised by men' (Mt 6:2), who want to be glorified by their own works; this is true idolatry. If, in doing my works, my good works, I do not seek the glory of God, but seek my own glory, I replace God and want to be the centre of attention, the subject that attracts applause and praise. If works have this negative aspect, we no longer have the light that shines.

The light of the Christian is his new life lived among men. A life made up of truth and charity, mercy and forgiveness. The diversity of life makes the difference, and this difference is transformed into the giving of glory to God. Today, it is precisely this difference that is lacking. If the difference does not exist, it is a sign that the works of the Christian are not of light.

Faith is not 'proved' but 'shown', simply, not through a demonstration, which is an intellectual fact, which may even smack of dialectics: convincing the other person. Faith is shown: the relationship you have with God and with others shines, makes you understand, makes you feel, communicates. Then the Father who is in heaven is glorified.

Our responsibility as Christians is great in every respect.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(Mt 5:1-12a)

Matthew 5:3 «Blessed are the poor in spirit,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven».

"Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven." Thus begins the first beatitude, the most important one, because it is placed first by Matthew. Let us first note the word 'blessed'. If we were to say to a poor person, 'blessed are you who are poor', we would be insulting them. We usually say, 'blessed are the rich'. Jesus' beatitudes are the exact opposite of what we think; they are words that radically overturn all earthly criteria. There is a truly subversive force in the beatitudes.

There is an imbalance of power between wealth and poverty, to the detriment of the poor, who are crushed by the greed and pride of the rich. In Jesus' message, poverty acquires a new dignity, unknown until then. Jesus came to restore dignity to humanity. In fact, for Jesus, it is necessary to free oneself from attachment to earthly goods in order to fully embrace his cause, which leads man to a higher and more fulfilled level of life. But this first level of material poverty is not enough. For Jesus, a further step is needed: to strip oneself of one's own way of thinking and seeing things, in order to take on that of God; it is necessary to place oneself on God's side and see things from his perspective.

There is a qualitative leap: from material poverty to inner poverty. Material poverty is not enough to inherit the kingdom, but must be rooted in the very heart of man. This is why Matthew says, 'Blessed are the poor in spirit'. Literally, poor in spirit can mean lacking in spirit, but Jesus cannot proclaim someone who is lacking in spirit to be happy.

The expression poor in spirit comes from Isaiah 66:2, whose Hebrew text says: 'ānî ûnekēh rûaḥ, 'This is the one I will look upon: the one who is poor and contrite in spirit'. The term 'ānî (poor) is related to 'ānāw (humble). In the LXX, it is often rendered as ptōchòs, which indicates the poverty of the beggar, forced to lower himself, to bow down, that is, to humble himself in order to survive. This conception of poverty will establish itself as a positive value especially after the Babylonian exile. The poor come to designate the humble, pious, God-fearing man. The 'ānāwîm, who turn to God in prayer and with faith, are poor people who belong to the lowest social classes. Despised and oppressed, they place their trust and security in God. They look to him alone for protection and help, with an inner attitude of humility and filial dependence.

Therefore, blessed poverty does not refer to a social situation, but rather implies trust in divine protection; it primarily refers to a spiritual attitude towards God. The poor in spirit are those who consider themselves beggars before God, who know that they cannot force the coming of the kingdom of heaven, but that it must be God who grants it to them.

Blessedness is now; it does not need to wait for the end of time. The verb in the phrase 'the kingdom of heaven is theirs' is in the present tense. That is, the kingdom is already theirs. And the kingdom of God is wealth. It is the realisation of the new world. Already now. The kingdom of heaven is not simply the afterlife. You suffer here, but you will be fine in the afterlife. No, the kingdom of heaven is God reigning over his own. Jesus does not say that the kingdom of heaven 'will be' theirs, he does not make a promise for the future, but says that it 'is' theirs, in the present.

Another thing should also be noted: Jesus does not speak in the singular, but in the plural. Jesus came to change human society. For this reason, it is not so much the gesture of the individual that is needed, but rather a community that radically changes its way of acting. This is the importance of the Church as a community.

To summarise, the poor are indeed those who lack riches, but 'in spirit' is added to show that it is not poverty itself that is acceptable to God, but that poverty which involves a detachment of the heart from worldly things, because those who are attached to worldly things are not willing to share them with their brothers and sisters. The poor in spirit are naturally also those who bear their poverty with patience, and all those who do not place their happiness in the accumulation of treasures. Jesus thus destroys the Jewish idea of a messianic kingdom founded on earthly power, and shows how detachment from riches is the first condition for sharing in the kingdom of heaven.

I understand that these words are difficult to understand and to live by: may the Lord grant us this. All the other beatitudes spring from the first. All the other seven beatitudes are nothing more than variations on the theme of poverty.

For example: 'Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted'. Here too there is the present beatitude: now you are blessed. Not because you are afflicted, but because you are comforted, just as the poor are blessed not because they are poor, but because the kingdom is theirs. The Lord comforts the afflicted. Comfort is a characteristic of God who does not leave the afflicted alone. The afflicted are those who suffer on earth because of human injustice. Every injustice always generates affliction. The greater the injustice, the greater the affliction.

It is interesting that blessedness is now in the present, but consolation is in the future. So what is there between the present and the future? There is the path to consolation. The positive meaning of history is that we will pass from affliction to consolation. On this path, the afflicted must live their affliction in holiness. Affliction is lived in holiness in only one way: by offering it to the Lord as a gift for the salvation of the world. Looking at Christ crucified, everyone can know who the truly afflicted are. Looking at Christ risen, everyone knows the greatness of God's consolations.

Let us look at it from another point of view. Have you ever seen a cheerful person being consoled? I never have! If he is cheerful, how can he be consoled? Divine bliss is a consolation for those who are afflicted, not for those who are cheerful. For there to be consolation, the person being consoled must be afflicted.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All Generations Will Call Me Blessed

Catholics and Protestants Compared – In Defence of the Faith

The Church and Israel According to St. Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(Mt 4:12-23)

Matthew 4:13 And leaving Nazareth, he came and dwelt in Capernaum, by the sea, in the territory of Zebulun and Naphtali,

Matthew 4:14 so that what had been said through the prophet Isaiah might be fulfilled:

Matthew 4:15 The land of Zebulun and the land of Naphtali,

on the road by the sea, beyond the Jordan,

Galilee of the Gentiles;

Matthew 4:16 the people who sat in darkness

have seen a great light;

on those who sat in the land and shadow of death

a light has dawned.

Matthew 4:17 From then on Jesus began to preach, saying, "Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand."

Verse 13 gives us the geography within which Jesus moves:

· leaving Nazareth;

· he came to live in Capernaum;

· by the sea;

· in the territory of Zebulun and Naphtali.

This geographical precision has a dual purpose: narrative and theological. Nazareth is the place of silence, where Jesus spent most of his life. We know very little about him during this period. The Son of God spends thirty years in an anonymous village. Doing what? Learning the craft of living, like every man, experiencing the days, the nights, the toil, the sweat, the heat, the cold, the joy: all the normal things of life. If he had not lived those thirty years, his incarnation would have made no sense. He lived our life in its everydayness; he truly took our life upon himself.

Leaving Nazareth, enclosed by hills and isolated, for Capernaum, a bustling town on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, located in a strategic place of considerable commercial and military importance, along the 'via maris', which connects Syria with Egypt, a crossroads of peoples, means turning over a new leaf, coming out into the open, giving a new direction to one's life. It was, therefore, an ideal place to proclaim the kingdom. It was from here that Jesus began his missionary activity. Capernaum became Jesus' second home. Most of Matthew's Gospel takes place here, in the town of Capernaum.

Leaving Nazareth for Capernaum, from the point of view of the narrative, means making a clear break between before and after and preparing the reader for something new that is about to happen. In fact, the meticulous geographical description of the place suggests that Matthew had other intentions than simply giving us the address of Jesus' new residence. In fact, he immediately tells us that this happens 'so that what had been said through the prophet might be fulfilled'. Therefore, what is happening here is not dictated by chance, but is following the evolution of a precise plan in action, which obeys the logic of a pre-established divine plan.

Jesus not only moves according to a pre-established plan, but is its fulfilment. Capernaum, in Galilee of the Gentiles, is a place halfway between Israel and the pagans. And since salvation is for both Israel and the pagans, this area, a mixture of Jews and pagans, is the most suitable place for the proclamation of the Gospel.

The people are immersed in darkness. Man makes darkness and death his home. It is precisely to this darkness that a great light is given. All of Jesus' activity is seen as light that dispels darkness. Light is the beginning of life (it is God's first creative act); light makes things what they are; without light, there is nothing. Salvation consists in enlightenment, that is, in opening our eyes to reality as God has given it to us and living accordingly.

Matthew reports a fact that was undoubtedly a surprise, if not a scandal, to the religious expectations of the time. In fact, it was logical to expect that the messianic announcement would come from the heart of Judaism, that is, from Jerusalem, but instead it came from a peripheral region, generally despised and considered contaminated by the pagan presence. Placed by Matthew in this geographical setting, Jesus gives a universal and revolutionary colour to his mission, announcing from the outset his departure from the traditional way of expecting salvation.

"From then on Jesus began to preach and say" (v. 17). Thus begins the activity of Jesus, who in reality does not begin to 'preach', but to proclaim, 'kēryssein', as the Greek text says. The difference between preaching and proclaiming is significant. Preaching is that tedious thing (for those who listen). Proclaiming, on the other hand, is publicly announcing a fact (which is quite different). A proclamation does not explain, it is an announcement of something. Proclamation is public. What does Jesus proclaim? The need for conversion.

He says something disruptive: 'metanoeite', an imperative that goes beyond a simple invitation to conversion. We could translate the term 'metanoeite' as 'change your way of thinking; reorient your thinking'. It is a matter of radically changing man, his inner self, and from there it must translate into a way of life conformed to God's requirements. The regeneration of man, therefore, must start from the level of being, and then be implemented on the level of action and living.

The need for this change lies in the fact that the kingdom of heaven is near. The kingdom of heaven is the kingdom of light. The kingdom of the prince of this world, on the other hand, is the kingdom of darkness. We must convert because Jesus came to establish the kingdom of light among us, and we can only enter this kingdom by abandoning the kingdom of the prince of this world. Conversion is the abandonment of the darkness of our minds and the complete surrender to the light that comes from the word of Christ. To those who were waiting for the kingdom of heaven, Jesus announces this good news: the kingdom of heaven is near. If it is near, prepare yourselves to enter it, and you enter through the narrow gate of conversion.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All Generations Will Call Me Blessed

Catholics and Protestants Compared – In Defence of the Faith

The Church and Israel According to St. Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(1 Corinthians 1:1-3)

1 Corinthians 1:1 Paul, called to be an apostle of Jesus Christ by the will of God, and brother Sosthenes,

1 Corinthians 1:2 to the Church of God which is at Corinth, to those who have been sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints together with all those who in every place call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, our Lord and theirs:

The sender and recipients of the letter to the Corinthians are indicated in a particularly solemn manner, which makes the beginning of this letter very important from a theological point of view. Paul is not doing something on his own initiative; no, he says he is 'called' by 'the will of God' to do what? To be an 'apostle of Christ', that is, an envoy of Christ. Paul represents Christ. This new life of his, that is, being an apostle of Jesus Christ, does not come from him but is by the will of God. God called him personally. That is why the Church must be apostolic, that is, founded on the testimony of the apostles. This is very important, because when someone comes to me and says, 'Look, there is someone who has had a revelation and has founded a new church,' let him keep his revelation and his church!

In other words, we need the historical testimony that goes back to those who saw Jesus. Our faith is not based on personal visions. Nor is it based on personal ideas or new theories, but on historical fact. First of all, the history of Israel, which culminates in Jesus, who is the ultimate revelation of God, and the apostles bear witness to this, that is, the apostles were sent to proclaim Jesus, and this tradition has been handed down to us. This is why the Church is essentially apostolic, not only for the past, but also for the future. The transmission continues. This is how Christianity has been transmitted. Paul is not alone in doing this; he is together with his brother Sosthenes. One is never alone; it is never a personal endeavour.

Paul addresses the 'church of God that is in Corinth'. There are not churches, but 'the church'. There are several communities where the church is present. Corinth is the local expression of a universal reality. The word church, from the Greek verb ekkaléō, from which the noun ekklēsia means to call out, that is, Christians are called out. From what and why? Called out to leave worldly categories, logic and philosophy of life. Called out to become aware of the truth. In other words, called out to be "sanctified in Christ Jesus" (v. 2). The "place" where sanctification takes place is Christ. We are sanctified in him. In him we become branches of his vine. Christ is the lifeblood of our sanctification. This is the new Christian consciousness that calls us out from others and then sends us to others, as if it were a paradox. So we are not called out to say that we do not care about others and go our own way, no! We are called out to make others understand too.

Holy means separate, that is, different. Diversity is the fact that we live in God's mercy. While the world lives in calculation, selfishness, self-interest, profit, under the domination of the slavery of fear of death, because they feel they are nobody's children and therefore must manage their lives as best they can, we, on the other hand, know that our lives are in the hands of God, who is our Father, who loved us, saved us, gave his Son for us, and our death is our encounter with Him. This is the radical holiness that makes us live differently.

The meaning of our life, then, is to become saints, that is, to become like Christ. Without having ideas of omnipotence: Christ died on the cross. We are called to develop all the power of grace and truth inherent in the Word of the Gospel. The Corinthians, says Paul, are saints by 'calling', that is, by divine initiative they have been chosen to believe and to be part of the people of God. The original text does not say 'called to be saints', but 'called saints'. Called to be saints gives the text an ethical meaning (will I succeed in becoming a saint?). Instead, the text wants to express an action of God: called saints; saints bear this name not because they have been good, but because they have been sanctified by God. The Church is holy as a community of people who benefit from divine action and vocation.

It is interesting, then, that this holiness is not a private matter, but we are called together with all those who in every place have received the same call. Not with those we choose, but 'with all' those who are 'in every place'. The vocation to holiness belongs to everyone together. Together we must strive for holiness, each with the other. Loneliness is not for Christians. This is the foundation of the catholicity of the Church, which is open. My fraternity is open, but if I do not live as a brother and begin to step on the toes of those on my right and left, what kind of Christian fraternity am I living? I realise fraternity first and foremost with the brothers I have not chosen. Those who do not love the brother they have not chosen love no one.

And what do those called to be saints do? "They call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ." Election is no longer only for the people of Israel, but for all those who call upon the name of the Lord in every place. This is a beautiful definition of a Christian: one who calls upon the name of the Lord Jesus Christ. Invocation is not simply a formal act, but something existential, vital, that is, a reference of life to Him. He is the one who gives meaning and significance to my existence. This then translates into practice with the liturgical acclamation to Christ, glorified as Lord of the Christian community and of the world.

In ancient times, invoking the name meant having a relationship, entering into communion with that person. A Christian is one who is in communion with Jesus as his Lord, as the one who loved me and gave himself for me. He loves me and I respond with my love, and this makes me like Him: a son. For this reason, invoking the name of Jesus is synonymous with salvation, not because of something magical, but because if I enter into communion with Him who is the Son, I become a son, and through Him I am in communion with the Father and with my brothers and sisters.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(Mt 3:13-17)

Matthew 3:13 At that time Jesus came from Galilee to the Jordan to be baptised by John.

Matthew 3:14 But John tried to prevent him, saying, 'I need to be baptised by you, and yet you come to me?

Matthew 3:15 But Jesus said to him, 'Let it be so now, for thus it is fitting for us to fulfil all righteousness.' Then John consented.

Matthew 3:16 As soon as Jesus was baptised, he came up out of the water, and behold, the heavens were opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and coming upon him.

Matthew 3:17 And behold, a voice from heaven said, 'This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased'.

After John had prepared the people with his words, awakening in everyone the expectation of the Messiah, Jesus reached the place where John was baptising, near the Jordan. He went to John to be baptised by him. We too find ourselves at the Jordan, because the text does not literally say that Jesus 'went', but that Jesus 'comes' (Greek paraginetai) to the Jordan. It assumes that we are there. We have listened to John's preaching, we have gone to the Jordan. To do what? To recognise ourselves as sinners.

And what does Jesus come to do? He comes to be baptised. He comes to be immersed, to go deep into human reality. This is the key to understanding the whole Gospel, where every passage shows how God enters our lives.

The Jordan is the river through which the Israelites entered the Promised Land. Therefore, it was right that Christ should be baptised in the Jordan, rather than in the Sea of Galilee or somewhere else.

We know that John's baptism is a baptism of water for conversion. The water that bathed the body was a sign of purification following repentance and confession of sins. Jesus is without sin. He does not need conversion. He has no guilt to repent of, nor any sin to confess. What use is baptism to him? None. This is John's thinking, and that is why he opposed it and prevented him from being baptised. Indeed, it is not right according to our criteria of justice. But Jesus will say that this is precisely how God's justice is fulfilled. Jesus does not baptise anyone; he does not baptise us, but we are baptised in him. That is, he did not come to put us under water; he came to go under water with us, and we are baptised in him in his death, that is, in his love for us. But if he is not baptised, that is, if he does not give his life for us, we cannot be baptised.

John does not know why Jesus asks to be baptised, and Jesus does not explain the reasons for his request. He refers John to the justice that must be done. All justice would be fulfilled in Jesus' submission to the rite of baptism. Jesus almost asks his permission to be baptised: 'let it be done', that is, allow it, grant it 'for now, because it is fitting'. It is good that I be baptised, it is fitting, it is necessary, because in this way 'all righteousness' is fulfilled, the will of God. 'For now' it is right that Jesus should accept the most humble position. It is precisely in this solidarity of the Son with mankind that God's will for the whole world is fulfilled. This is how God's plan is fulfilled. Therefore, Jesus' baptism, his death, is the fulfilment of all God's justice, for the cross is his judgement. His judgement is to give his life for all mankind, and he gives it in the Son.

It is difficult for us to understand that all justice is fulfilled in the fact that Jesus is in solidarity with us. The whole of Scripture is fulfilled in the fact that the Son was counted among the evildoers. John was right to be scandalised! We are not scandalised because we probably cannot understand how the Just One can be considered an evildoer and a sinner. By allowing himself to be baptised by John, it is as if Jesus stripped himself of his will. There is a will of the Father that he must fulfil. In baptism, Jesus surrenders his will to the Father, strips himself of his will, and officially accepts the mission of being the Messiah of God, and also accepts to fulfil the mission always and only in full observance of the Father's will.

Jesus immersed in water is a figure of Jesus dead on the cross; his lowering, but followed by his rising up. And behold, Jesus "came up out of the water". The adverb used by Matthew, euthys (immediately, right away), is very interesting, indicating the immediacy of what follows. This means that the evangelist wanted to tell us that not much time passed between Jesus' descent into the water and his ascent, but that it was almost immediate or at least rapid (Jesus seems to splash out). Jesus does not remain in the water, symbol of his own death, but comes out of it, where the Father's response from heaven awaits him. 'The heavens opened'. The sky is a symbol of God. The earth is joined with the sky in this scene, and in fact the Spirit of God descends. The heavens opening: this tells us of God's irruption into human history. God communicates with humanity.

Jesus is the one through whom the Father visits and encounters human beings. Jesus, therefore, is the historical place of encounter between God and human beings. The salvation of humanity therefore rests on the baptised man Jesus. In Matthew's Gospel, Jesus' mission begins and ends with the theme of baptism. If Jesus' first act is to undergo baptism, his last words will be an invitation to his disciples: "Go and baptise all peoples". Baptism opens and closes Jesus' activity. The sending of the apostles to baptise is an invitation to make God known to all humanity, the God whom they have experienced and known, and whom they have made known to us.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All Generations Will Call Me Blessed

Catholics and Protestants Compared – In Defence of the Faith

The Church and Israel According to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(John 1:1-18)

John 1:1 In the beginning was the Word,

and the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.

John 1:12 But to all who did receive him,

he gave them the right to become children of God:

to those who believe in his name,

John 1:13 who were born, not of blood,

nor of the will of the flesh,

nor of the will of man,

but of God.

"... to those who believe in his name" (v. 12). Significant is that "in" rendered in Greek as "eis", a particle of motion to a place. It expresses a movement oriented towards, imprinting on belief the dynamic proper to life, understood as a journey in Christ and for Christ. Believing in his name, therefore, means not only accepting, but orienting and conforming one's life to Christ. Only under these conditions can one obtain the "power," that is, the ability, to become children of God. Faith, therefore, enables one to acquire the capacity for divine sonship, because believing is walking towards Christ, growing in him. Only under these conditions does the believer "become" a child of God, that is, pass from a human condition to a divine one. A 'becoming' that is an evolutionary and transformative process, 'from ... to', which commits the believer's life, understood as a continuous becoming, significantly expressed in the particle 'eis'.

Verse 13 explains where the generation of God's sons comes from. Divine sonship does not depend on man: a) 'not of blood'; b) 'nor of the will of the flesh'; c) 'nor of the will of man'. Flesh, blood and man are three terms that are only apparently synonymous with each other; in reality, they indicate three types of people.

The first expression 'not of blood' in Greek is rendered in the plural ('ouk ex haimátōn', not of bloods). For Jews, blood is the seat of life; indeed, it is sometimes identified with life itself. This blood is always referred to in the singular. However, if blood flows from the body due to a wound or female menstruation, it is referred to in the plural, i.e. 'bloods'. These two aspects, wound and menstruation, refer respectively to circumcision, through which the child was incorporated into the people of Israel and thereby made heir to the divine promise, and to the generative capacity of women. Neither of these two types of blood is capable of giving divine sonship. While the blood that flows from the wound of circumcision is understandable, that of female menstruation is less clear, so let us pause for a moment to make it easier to understand. The use of the plural form of blood in this context, referring to the generation of divine sonship, recalls the generative capacity of women, which in the Jewish world was considered the sure element of Jewishness. A true Jew was someone born of a Jewish mother. Therefore, to say that the true sons of God do not come 'from the blood' was to say that it is not the Jewish people who generate them, neither through their women nor, even less so, through circumcision. This expression, 'ouk ex haimátōn', therefore, refers to the Jewish people and excludes their ability to generate true divine sonship. The true sons of God are not generated by Moses or by the Law. The denial of these two types of blood in terms of their generative capacity for the divine assigns this capacity to another blood and another flesh, those of Jesus.

The second expression, 'nor from the will of the flesh', closely recalls the state of conjugality between man and woman. That 'will', far from indicating a lustful desire, indicates the planning ability of man and woman, their capacity to determine their own future according to their own plans and designs. Divine sonship, therefore, does not even depend on the will of the spouses, understood in their innate generative capacity, which makes them fruitful and similar to God, the generator of life.

The third expression, 'nor from the will of man', captures man in his capacity for self-determination. The term used here to refer to man is not 'ánthrōpos', which means man in a generic sense and has its Latin equivalent in 'homo', but 'anēr', which contains within itself the meaning of man par excellence and has its Latin parallel in 'vir'. Therefore, even from this human excellence, made in the image and likeness of God, true divine sonship will not come forth. Thus, with the human realm in its three different facets excluded, only the divine realm remains, introduced by an adversative "but": "but they were begotten by God".

True divine sonship has its origin and roots exclusively in God. No human merit can boast divine generative capacity. Through faith and acceptance of the Word, the transition from fleshly nature to divine nature is effected in man. It is in this transition that lies the surprising novelty of the Christian in the face of the non-Christian.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

(Mt 1:18-24)

Matthew 1:19 Joseph her husband, being a just man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, resolved to divorce her quietly.

When we read this verse, we feel entitled to enter Joseph's mind, take his place and reflect our own thoughts, conjectures and fantasies in the text.

Joseph is defined here as a 'just man', dikaios; and this verse expresses Joseph's drama, which is the drama of every just person. What exactly does this righteousness allude to? Certainly not to the fact that he decided not to expose Mary to any judgement, with possible tragic consequences for her; nor to the fact that he wanted to repudiate her secretly, since Joseph was already 'righteous' before these things happened. The "righteous" person, biblically speaking, is one who faithfully practises the Torah. The Jewish religion, in fact, is the religion of orthopraxy, the correct execution of what God commands, without first wanting to understand. God's commandment is a will that must simply be carried out. The righteous person, therefore, is one who knows how to conform and faithfully carry out what the Torah commands. Yet in this case, Joseph does not apply the Torah, which would require repudiation, divorce, and possibly stoning.

So in what sense is Joseph righteous? According to one interpretation, 'righteous' should be understood in the sense of 'good': Joseph has his suspicions, but he is a 'good' man, he has a 'good heart', he will not make a scene and will separate from Mary in silence. But dikaios never has the meaning of 'good'.

In reality, 'righteous' must have the typical meaning given to it by Matthew, that is, acceptance of God's plan, however disconcerting it may be. Joseph, being a righteous man, from the height of his righteousness thinks only of what is good, but not of his own good, rather that of Mary. And what is good for Mary? It is not to repudiate her publicly. This would have exposed Mary, at the very least, to the ridicule of the people. The good, therefore, consists in quietly and silently leaving Mary's life. This means 'dismissing her in secret'. He would have withdrawn without anyone knowing anything. The 'just' man is the one who respectfully withdraws before God's intervention.

'He did not want to repudiate her' translates the Greek verb 'deigmatìsai', a very rare verb. Therefore, there are divergent translations and interpretations: 'he did not want to expose her to infamy'; 'he did not want to publicly disgrace her'; 'he did not want to expose her to public ridicule', all versions that seem to imply that Joseph considered Mary guilty. The question is whether this rare Greek verb should have a pejorative meaning or not. In one of his writings, the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea observes that "deigmatisai" simply means "to make known", "to bring to light". Something that is unknown and is subsequently revealed may be good or bad, edifying or shameful; but the word itself means 'to expose, or to propose as an example', 'to appear', 'to show'. So Joseph does not want to expose the fact, he does not want to make it appear, he does not want to show it publicly.

"He decided to dismiss her" translates the Greek "apolysai", which refers to the meaning of "free", "dissolve", "acquit". So it can simply mean "to set free", "to let go", but it can also have the meaning of "to dissolve, to break the bonds of marriage". According to some, it could therefore mean 'to repudiate', 'to divorce'. In this case, it should be interpreted as if Joseph wanted to give Mary a certificate of repudiation to submit to the court in order to obtain a divorce. But this is a hard-line interpretation. Technically speaking, the word can only mean 'to divorce' with a certain amount of stretching. But since divorce is a public act, performed before witnesses, and here the verb is accompanied by the adverb 'lathra' ('secretly, covertly'), a public act cannot be performed in secret.

Alternative translation: "Joseph, her husband, who was just and did not want to expose her, decided to separate from her in secret." If we read the verse from this perspective, its tone changes completely. Joseph could not say in public what Mary had revealed to him in confidence; he had to keep it in his heart as a precious secret. But what was he to do? Filled with religious awe at the mystery that had taken place in Mary, his wife, Joseph saw no other way out at that moment than to withdraw discreetly. Thus, the very idea of a denunciation vanished completely. The perspective was radically reversed. Full of respect for Mary, in whom the Holy Spirit had accomplished such great things, Joseph was ready to surrender her totally to God.

Other interpretations start from assumptions such as that Joseph had not been informed of Mary's virginal conception. Being righteous, he could not in conscience live with a sinner, in contrast to the law of the Lord. This is the traditional hypothesis, but it does not take into account the Christological and non-historiographical intent of the evangelist. Therefore, two opposing directions are possible in the interpretation: one severe and the other more moderate, which leaves the way open to a favourable explanation.

We must open ourselves to something much greater than we can imagine. The very virgin conception of Mary must be experienced by every believer, that is, being willing to accept something infinite. Only in this way can we receive God's gift. Why did Mary conceive the Word of God? Simply because, being humble and knowing that she did not deserve it, she did not say, 'I do not deserve it, so I reject it'; but being humble, she said, 'I receive it as a gift'.

The humble desire God, while the proud desire something they can do themselves. Paradoxically, it would be the proud person who is right because he knows his limits, his duties, his obligations; since he is right, he stops there: I know myself, I know my limits and I stop. And Joseph reasons in this way. This thing is too big for me, it is not for me, so I remain outside God's gift. It would be like going to work for an hour and being given five million; you say: no, that's not right. So it is with grace: it requires humility to accept it.

Let us think if Mary, when the angel said to her, 'The Lord is with you, you will conceive a son', Mary had replied: perhaps you are mistaken, I am not worthy, go to someone else. We often say that! It means that the Word is not rooted in us, because of our sense of unworthiness that does not come from God. God does not give us a sense of unworthiness, He gives us a sense of humility and welcomes us so that we can welcome the gift. So we enter into the Gospel with this openness of heart to welcome the impossible, because the gift that God gives us is impossible, it is Himself.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

Anyone who welcomes the Lord into his life and loves him with all his heart is capable of a new beginning. He succeeds in doing God’s will: to bring about a new form of existence enlivened by love and destined for eternity (Pope Benedict)

Chi accoglie il Signore nella propria vita e lo ama con tutto il cuore è capace di un nuovo inizio. Riesce a compiere la volontà di Dio: realizzare una nuova forma di esistenza animata dall’amore e destinata all’eternità (Papa Benedetto)

You ought not, however, to be satisfied merely with knocking and seeking: to understand the things of God, what is absolutely necessary is oratio. For this reason, the Saviour told us not only: ‘Seek and you will find’, and ‘Knock and it shall be opened to you’, but also added, ‘Ask and you shall receive’ [Verbum Domini n.86; cit. Origen, Letter to Gregory]

Non ti devi però accontentare di bussare e di cercare: per comprendere le cose di Dio ti è assolutamente necessaria l’oratio. Proprio per esortarci ad essa il Salvatore ci ha detto non soltanto: “Cercate e troverete”, e “Bussate e vi sarà aperto”, ma ha aggiunto: “Chiedete e riceverete” [Verbum Domini n.86; cit. Origene, Lettera a Gregorio]

In the crucified Jesus, a kind of transformation and concentration of the signs occurs: he himself is the “sign of God” (John Paul II)

In Gesù crocifisso avviene come una trasformazione e concentrazione dei segni: è Lui stesso il "segno di Dio" (Giovanni Paolo II)

Only through Christ can we converse with God the Father as children, otherwise it is not possible, but in communion with the Son we can also say, as he did, “Abba”. In communion with Christ we can know God as our true Father. For this reason Christian prayer consists in looking constantly at Christ and in an ever new way, speaking to him, being with him in silence, listening to him, acting and suffering with him (Pope Benedict)

Solo in Cristo possiamo dialogare con Dio Padre come figli, altrimenti non è possibile, ma in comunione col Figlio possiamo anche dire noi come ha detto Lui: «Abbà». In comunione con Cristo possiamo conoscere Dio come Padre vero. Per questo la preghiera cristiana consiste nel guardare costantemente e in maniera sempre nuova a Cristo, parlare con Lui, stare in silenzio con Lui, ascoltarlo, agire e soffrire con Lui (Papa Benedetto)

In today’s Gospel passage, Jesus identifies himself not only with the king-shepherd, but also with the lost sheep, we can speak of a “double identity”: the king-shepherd, Jesus identifies also with the sheep: that is, with the least and most needy of his brothers and sisters […] And let us return home only with this phrase: “I was present there. Thank you!”. Or: “You forgot about me” (Pope Francis)

Nella pagina evangelica di oggi, Gesù si identifica non solo col re-pastore, ma anche con le pecore perdute. Potremmo parlare come di una “doppia identità”: il re-pastore, Gesù, si identifica anche con le pecore, cioè con i fratelli più piccoli e bisognosi […] E torniamo a casa soltanto con questa frase: “Io ero presente lì. Grazie!” oppure: “Ti sei scordato di me” (Papa Francesco)

Thus, in the figure of Matthew, the Gospels present to us a true and proper paradox: those who seem to be the farthest from holiness can even become a model of the acceptance of God's mercy and offer a glimpse of its marvellous effects in their own lives (Pope Benedict))

Nella figura di Matteo, dunque, i Vangeli ci propongono un vero e proprio paradosso: chi è apparentemente più lontano dalla santità può diventare persino un modello (Papa Benedetto)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.