don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Ash Wednesday [18 February 2026]

May God bless us and the Virgin protect us! I am now sending the texts for Ash Wednesday and Wednesday those for Sunday.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Joel (2:12-18)

'Return to the Lord with all your heart'. The book of the prophet Joel is one of the shortest in the Old Testament: it has only seventy-three verses, divided into four chapters, and is generally dated around 600 BC, shortly before the Exile to Babylon. Three major themes are constantly interwoven in this writing: the announcement of terrible scourges, real or symbolic; the urgent call to fasting and conversion; and finally, the proclamation of the salvation that God grants to his people. It is above all the second theme, that of conversion, which the liturgy proposes at the beginning of the Lenten journey. The invitation to conversion opens solemnly with the typical formula of the prophets: "The word of the Lord." It draws attention and asks us to take seriously what follows. And what follows is a decisive word: "Return". It is the fundamental verb of biblical penitential language. God invites his people to return to him, while the people, in turn, implore God to "return", that is, to grant forgiveness and mercy. This return to God must be expressed through fasting, tears and mourning: traditional signs of penance. However, the prophets, and Joel in particular, warn against the risk of stopping at outward appearances. For this reason, the prophet strongly affirms: "Rend your hearts and not your garments". Authentic conversion is not a matter of visible rituals, but a profound change of heart. Joel thus follows in the great prophetic tradition inaugurated by Isaiah, who denounced empty and formal worship, incapable of transforming life: God rejects solemn feasts and multiplied prayers when hands remain stained with injustice. What He asks for is a true purification of the heart and actions, the abandonment of evil and a concrete commitment to good and justice. The same message is expressed in a particularly intense way in Psalm 50/51, which defines true conversion as a "broken and humbled heart". In the light of Ezekiel, this image takes on an even deeper meaning: it is necessary for the heart of stone to be broken so that a heart of flesh may finally be born, capable of listening to God and living according to his will. When Joel calls for hearts to be torn, he means precisely this radical transformation of the human being. Conversion, in Joel's view, aims to obtain God's forgiveness and avert deserved punishment. The prophet reminds us that the Lord is 'tender and merciful, slow to anger and rich in love' and leaves open a hope: perhaps God will retrace his steps, renounce punishment and save his people from humiliation before the nations. But the final announcement exceeds all expectations: forgiveness is not only possible, it has already been granted. The liturgical translation speaks of a God who is 'moved' by his people, but the Hebrew text is even stronger: 'The Lord burns with zeal for his land and has compassion on his people'. This is not a cold or distant pity, but a passionate and faithful love. It remains to be discovered in biblical revelation that this mercy is not reserved for Israel alone. The book of Jonah shows this in a surprising way, recounting the conversion of Nineveh, the pagan city: faced with the fasting and change of life of its inhabitants, God renounces the punishment he had announced. The message is clear: the Lord "burns with zeal" for all people, even those who seem distant or unworthy.

This truth will find its definitive expression in the New Testament, when St Paul affirms that God has manifested his love in a radical way: Christ died for us while we were still sinners (Rom 5:8).

*Responsorial Psalm (50/51)

"Have mercy on me, O God, in your love; in your great mercy blot out my guilt. Wash me clean of my guilt, purify me from my sin." The people of Israel are gathered in the Temple in Jerusalem for a great penitential celebration. They recognise themselves as sinners, but they also know God's inexhaustible mercy. And, after all, if they gather to ask for forgiveness, it is precisely because they know in advance that forgiveness has already been granted. This was the great discovery of King David, who had brought his beautiful neighbour Bathsheba (the wife of an officer, Uriah, who was at war at the time) to his palace and slept with her, and she became pregnant. Some time later, Bathsheba let David know that she was expecting his child. At that point, David arranged for the death of her betrayed husband on the battlefield, so that he could definitively take possession of the woman and the child she was carrying. Now, and this is where God's unexpectedness comes in, when the prophet Nathan went to David, he did not first try to extract a confession of repentance from him; instead, he began by reminding him of all the gifts he had received from God and announcing his forgiveness, even before David had had time to make the slightest admission of guilt (cf. 2 Sam 12). In essence, he said to him, 'Look at all that God has given you... and know that he is ready to give you anything else you want!'. Israel has always been able to verify that God is truly a merciful and compassionate Lord, slow to anger, rich in faithful love, according to the revelation made to Moses in the desert (Ex 34:6). The prophets also reiterated this message, and the verses of the psalm we have heard are imbued with the discoveries of Isaiah and Ezekiel. Isaiah, for example, has God say: "I, even I, am he who blots out your transgressions for my own sake, and I will not remember your sins" (Isaiah 43:25). The proclamation of God's gratuitous forgiveness sometimes surprises us: it seems too good to be true; to some it even seems unfair. If everything is forgivable, what is the point of making an effort? It is to forget too quickly that all of us, without exception, need God's mercy: so let us not complain about it! And let us not be surprised if God surprises us, because, as Isaiah says, "God's thoughts are not our thoughts". And in forgiving, Isaiah points out, God surprises us more than anything else. Faced with the ever-renewed proclamation of God's mercy, the people of Israel recognise themselves as sinners. The confession is not detailed, as it never is in the penitential psalms, but the essential is said in this supplication: Have mercy on me, O God, in your love, in your great mercy, blot out my sin... And God, who is all mercy, expects nothing more than this simple recognition of our poverty. After all, the word 'mercy' has the same root as the word 'alms': literally, we are beggars before God. At this point, we have two things left to do.

Simply give thanks for this forgiveness that is continually given. When Israel turns to God, it always acknowledges the goodness with which He has filled it since the beginning of its history, and this shows that the most important prayer in a penitential celebration is the acknowledgement of God's gifts and forgiveness: we must begin by contemplating Him; only then, this contemplation, revealing the gap between Him and us, allows us to recognise ourselves as sinners: we confess God's love together with our sin. Then the song of gratitude will flow spontaneously from our lips when God opens our hearts. "Lord, open my lips, and my mouth shall proclaim your praise" (Psalm 50/51). Praise and thanksgiving can only arise in us if God opens our hearts and our lips. The second thing God expects of us is to forgive in turn, without delay or conditions... and that is quite a programme.

*Second reading from the second letter of St Paul to the Corinthians (5:20-6:2)

"Be reconciled to God," says Paul; but reconciliation implies that there is a quarrel: what quarrel is it? The men of the Old Testament discovered that God is not at odds with man. Psalm 102/103, for example, states: The Lord does not always contend, nor does he keep his anger forever; he does not treat us according to our sins, nor repay us according to our iniquities... Isaiah also invites the wicked to abandon their ways, the unrighteous to abandon their thoughts; return to the Lord, who will have compassion on you, to our God, who forgives abundantly (Is 55:7). And the book of Wisdom adds: 'You have mercy on all because you can do all things, and you turn away your gaze from the sins of men to lead them to repentance... You spare them all, because they are yours, Lord, who loves life... Your dominion over all makes you use clemency towards all' (Wisdom 11:23; 12:16). The men of the Bible experienced this, beginning with David. God knew that he had blood on his hands (after the killing of Uriah, Bathsheba's husband, 2 Sam 12), yet he sent the prophet Nathan to tell him in essence: "Everything you have, I have given you, and if that is not enough, I am ready to give you everything else you desire." God also knew that Solomon owed his throne to the elimination of his rivals, yet he listened to his prayer at Gibeon and granted it far beyond what the young king had dared to ask (1 Kings 3). Furthermore, God's very name — the Merciful One — means that he loves us even more when we are miserable. God, therefore, is not at odds with man; yet Paul speaks of reconciliation, because man has always been at odds with God. The text of Genesis (Genesis 2-3) attributes the accusatory phrase to the serpent: "God knows that on the day you eat of it, your eyes will be opened and you will be like gods, knowing good and evil" (Gen 3:4). In other words, man suspects that God is jealous and does not want his good. But since that voice is not natural to man (it is the serpent's), he can be healed of this suspicion. This is what Paul says: "It is God himself who calls you; we urge you in the name of Christ: be reconciled to God." And what did God do to remove this quarrel, this suspicion, from our hearts? He who knew no sin, God made him sin for us: Jesus knew no sin even for a moment, he was never at odds with the Father. Paul adds: 'He became obedient' (Phil 2:8), that is, trusting even through suffering and death. He sought to communicate to men this trust and the revelation of a God who is only love, forgiveness, and help for the little ones. Paradoxically, it was precisely for this reason that he was considered blasphemous, placed among sinners and executed as a cursed man (Deut 21:23). The darkness of men fell upon him, and God allowed it because it was the only way to make us realise how far his "zeal for his people" can go, as the prophet Joel says. Jesus suffered in the flesh the sin of men, their violence, their hatred, their rejection of a God of love. On the face of the crucified Christ, we contemplate the horror of human sin, but also God's gentleness and forgiveness. From this contemplation can come our conversion, our 'justification', as Paul says. They will look upon him whom they have pierced (cf. Zechariah 12:10; John 19:37). To discover in Jesus, who forgives his executioners, the very image of God means to enter into the reconciliation offered by God. We are left with the task of proclaiming this to the world: 'We are ambassadors for Christ', says Paul, considering himself sent on mission to his brothers and sisters. It is up to us to continue this mission, and this is probably the meaning of Paul's final quotation: "For it is written in Scripture: 'At the favourable time I answered you, on the day of salvation I helped you.'" Paul here takes up a phrase from Isaiah, who exhorted the Babylonian exiles to proclaim that the hour of God's salvation had come. In turn, Christ entrusted to the Church the task of proclaiming the forgiveness of sins to the world.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (6:1-6, 16-18)

Here we have two short excerpts from the Sermon on the Mount, which occupies chapters 5-7 of St Matthew; the entire sermon is built around its central core, the Lord's Prayer (6:9-13), which gives meaning to everything else. The recommendations we read today are not just moral advice: they concern the very meaning of faith. All our actions are rooted in the discovery that God is Father. Thus, prayer, almsgiving and fasting become paths to bring us closer to God the Father: fasting means learning to go out of ourselves, praying means centring ourselves on God, giving alms means centring ourselves on our brothers and sisters. Three times Jesus repeats similar, almost polemical formulations: Do not be like those who flaunt their piety.... It is important to remember how significant religious manifestations were in Jewish society at the time, with the inevitable risk of attributing too much value to outward gestures; and probably even prominent figures did not escape this! Matthew sometimes reports Jesus' rebukes to those who focused more on the length of their fringes than on mercy and faithfulness (Mt 23:5f). Here, however, Jesus invites his disciples to a truth operation: If you want to live as righteous people, avoid acting in front of others to be admired. Righteousness was the great concern of believers: and if Jesus mentions the pursuit of righteousness twice in the Beatitudes, it is because that term, that thirst, was familiar to his listeners: "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied" (5:6); "Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven" (5:10). True biblical justice consists in harmony with God's plan, not in the accumulation of practices, however noble they may seem. The famous phrase from Genesis — Abraham believed in the Lord, and it was credited to him as righteousness (Gen 15:6) — teaches us that justice is first and foremost righteousness, as in a musical instrument, a deep harmony with God's will.

The three practices — prayer, fasting, almsgiving — are paths to righteousness.

Prayer: let God guide us according to his plan: "Hallowed be thy name, thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven." We wait for Him to teach us the true needs of the Kingdom. Jesus precedes the teaching of the Our Father with this recommendation: "When you pray, do not do as the pagans do... your Father knows what you need before you ask him (6:7-8).

Fasting: by ceasing to pursue what we believe is necessary for our happiness, which risks absorbing us more and more, we learn freedom and recognise true priorities; Man does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God (Mt 4:4).

Almsgiving: The word almsgiving comes from the same family as eleison: to give alms means to open one's heart to mercy. God wants the good of all his children; justice, understood as harmony with Him, inevitably includes a dimension of social justice. The parable of the Last Judgement (Mt 25:31-46) confirms this: "Come, blessed of my Father... for I was hungry and you gave me food... and the righteous will enter into eternal life." The behaviours that Jesus condemns — do not be like those who show off — are the opposite: they keep man centred on himself, closing his heart to the transforming action of the Spirit.

+Giovanni D'Ercole

(Lk 9:22-25)

Yesterday we underlined how the worm of vanity in the search for the esteem leads to hypocrisy and ostentation.

We ask ourselves: what makes the Father intimate? Carrying the Cross - in the sense of being a devoted and obedient child? Is it necessary to give up living, accepting the various evils?

No, communion with God follows from a freely assumed commitment. That scaffold is not a requirement of the Father who would like to be ‘compensated’ at least by someone.

There are not many ways to choose from, but only two: victory or gift, and every moment is a time of decision.

Templates are no longer needed.

A comparison between the parallel texts in Greek (for example) of Mk 8:34; Mt 10:38; Lk 9:23 and 14:27 [Jn 12:26] makes us understand the meaning of «taking up» or «lifting up the cross» for a disciple who relives Christ and expands him in human history.

God doesn’t give any cross, nor are his sons called to "bear" it or even "offer it"! The Cross must be actively ‘taken’, because the friend of Jesus puts honor at stake.

Its vital wave reaches complete gift also under the profile of public consideration.

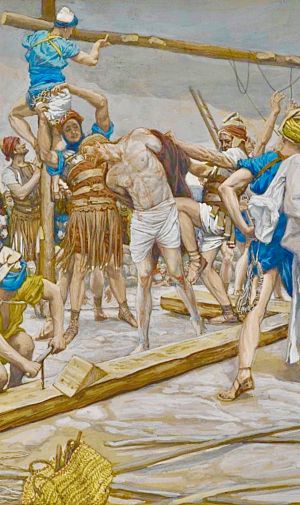

After the court sentence, the condemned man had to lift the horizontal arm of the gallows on his shoulders.

It was the most heartbreaking moment, because of maximum loneliness and perception of failure.

Thus the unfortunate and already shamed person had to proceed to the place of the crucifixion by passing between the crowd who, for religious duty, mocked and beat up the wretch, considered cursed by God.

Jesus doesn’t propose the Cross to us in the running sense of a necessary endurance of the inevitable setbacks of life which through asceticism chisels souls more capable of sketching [today we say: ‘resilient’].

Compared to the usual proposals of healthy discipline - external and internal - equal for all and useful only to keep the situation good, the young Rabbi is on the other hand suggesting a much more radical behavior.

The Lord proposes an asceticism totally different from that of religions - even overturned.

The believer must give up ‘reputation’. It’s the essential and decisive starting point of the person of Faith.

Those who are tied to their good names, roles, to the character to be played, to the job description, to the level acquired, will never resemble the Son.

Neither will those who do not expand the tribal dimension of the "family” interest.

From the earliest times, the announcement of the authentic Messiah created divisions: the ‘sword of his Person’ separated the story of each one from the world of values of the clan to which they belong or from the idea of respectability, even national.

The same thing happens today where someone proclaims the Gospel as it is, and attempts to renew the jammed mechanisms of the institutional, customary configuration.

In doing so, taking on the Cross of consequent mockery.

The separation and very clear cut with the criteria of greatness and success is for the new Unity, persecuted: the one that acts as a crossroads of Truth without duplicity.

Trying for believing.

It seems a meaningless dream, but this is what unites the Church to her Lord.

A crucifying path, where one gains what is lost - first of all in consideration.

[Thursday after the Ashes, February 19, 2026]

(Lk 9:22-25)

Yesterday we emphasised how the worm of vanity in the pursuit of others' esteem leads to hypocrisy and ostentation.

Today, too, the Word - a solemn and pressing call to a decisive choice - invites totality; to live Lent with uprightness, not exhibiting too much external ceremony.

We ask ourselves: What makes one intimate with the Father? Carrying the Cross - in the sense of being a devoted and obedient son? Is it necessary to renounce life, accepting the various evils?

No, communion with God follows from a freely made commitment. That scaffold is not a requirement of the Father who would like to be at least compensated by someone.

And no fatalism: it is not a matter of enduring life's inevitable setbacks.

It is not this that unites, it is not coping that binds the people of God who recognise themselves in the Crucified One.

There are not many paths to choose from, but only two: victory and revenge, or perception and gift.

Every moment is a time of decision. Models are no longer needed.

Man's authenticity is not his greatness, but fidelity in the love that he realises.

Such empathy and can place us on paths of persecution and derision, instead of accommodating or blatant results (on the safe and immediate).

But true humanity no longer needs to ascend, to transcend the limits of matter [dualist mysticism].

Nor do we need to identify ourselves - almost sacramentally - with the forces of deep but depersonalising cosmic processes [mystery religions].

We are not called to perfect ourselves through the observance of a law or traditions down to the minutiae [phariseeism].

Nor is our vocation to religiously escape the abyss of the world's misery, in the hope of a goal approaching to solve everything [Apocalypticism].

The Lord's Anointed was expected as sovereign, priest, thaumaturge, warrior, judge, prophet...

Jesus ascending Calvary is quite another paradigm: a different way of being and an entirely different Way.

To the title of Messiah, Luke prefers that of "Son of Man" (v.22): an expression with which the Master actually designated himself.

The Son of Man is the true and full development of the divine plan on humanity.

Incredibly, He does not feel hindered by frequenters of bad places, rather by the habitués of the sacred precincts.

In the Gospels, the growth and humanisation of the people is not thwarted by sinners, but by those who would have the ministry of making the Face of God known to all.

Therefore, the character of the apostle is not identified with celebrities and social figures. Conversely, with the life of Jesus of Nazareth - the public rebel against official authorities, and condemned.

Here, moving downwards, we meet God.

That of the cross was in fact the torture imposed on marginalised criminals. In this lies the 'denial of self' (v.23), which unfortunately in the history of spirituality has undergone very bad interpretations.

The believer is not recognised by heroic and magnificent deeds, or asceticism; nor by excellence and visibility of office, or charisma and credit, weight and prestige - but by social choice, which brings discredit to one's reputation.

The missionary is not singled out because of extraordinary qualities, but because of smallness.

He who only appreciates great things - even astounding and blatant from a "spiritual" point of view - loves strength. And they do not build the new kingdom.

A comparison of the parallel texts in the Greek language (e.g.) of Mk 8:34; Mt 10:38; Lk 9:23 and 14:27 [Jn 12:26] gives insight into the meaning of "taking up" or "lifting up the cross" for a disciple who relives Christ and expands Him in human history.

God does not give any cross, nor are children called to "bear" it, or even "offer" it!

The Cross is to be actively taken up, for the friend of Jesus stakes his honour on it.

The eminent and crystal-clear Source, the intimate life-wave of its founding Eros, allows the total gift to be attained even under the trait of public consideration.

After the court sentence, the condemned man had to carry the horizontal arm of the gallows on his shoulders.

It was the most harrowing moment, because it was one of utmost loneliness and perceived failure.

The hapless and already shamed man proceeded to the place of execution passing between two wings of the crowd who, out of religious duty, mocked and battered the wretch - deemed cursed by God.

Jesus does not propose the Cross in the corrupt sense of a necessary endurance of life's inevitable adversities, which then through asceticism chisels out souls more capable of sketching... [today we say: resilient].

Compared to the usual tirades on healthy discipline - exterior and interior - the same for everyone (and useful only to keep the situation good, of privilege) Lk is conversely suggesting a much more radical behaviour.

The Lord proposes an asceticism totally different from that of the religions - even inverted.

The believer renounces reputation. It is the essential, diriment cue of the character of the Faith.

He who is tied to his good reputation, to the roles, to the character to play, to the task, to the level he has acquired, will never resemble the Lord.

Neither will he who does not dilute the tribal dimension of 'family' interest.

From the earliest times, the proclamation of the authentic Messiah created divisions: the sword of his Person separated each person's affair from the world of values of the clan to which he belonged or from the idea of respectability, even national respectability.

Today, the same thing happens where someone proclaims the Gospel as it is, and attempts to renew the jammed mechanisms of the habitual, outdated and faux-blue-blooded institution on the ground.

Carrying the cross of consequent mockery.

A clean break and cut with the criteria of greatness and success, for the new, persecuted Unity: the one that is the crossroads of Truth without duplicity.

Try it to believe.

It sounds like a meaningless dream, but this is what unites the Church to her Lord: a crucifying path, where one gains what one loses - first and foremost in consideration.

To internalise and live the message:

What changes do you feel as your Calling?

Does reputation and opinion in the community favour or block you? For what reason?

Is your 'family' closed in on itself or does it facilitate the opening of horizons?

Does this attitude of the Christians of that time apply also to us who are Christians today? Yes, it does, we too need a relationship that sustains us, that gives direction and content to our lives. We too need access to the Risen one, who sustains us through and beyond death. We need this encounter which brings us together, which gives us space for freedom, which lets us see beyond the bustle of everyday life to God’s creative love, from which we come and towards which we are travelling.

Of course, if we listen to today’s Gospel, if we listen to what the Lord is saying to us, it frightens us: “Whoever of you does not renounce all that he has and all links with his family cannot be my disciple.” We would like to object: What are you saying, Lord? Isn’t the family just what the world needs? Doesn’t it need the love of father and mother, the love between parents and children, between husband and wife? Don’t we need love for life, the joy of life? And don’t we also need people who invest in the good things of this world and build up the earth we have received, so that everyone can share in its gifts? Isn’t the development of the earth and its goods another charge laid upon us? If we listen to the Lord more closely, and above all if we listen to him in the context of everything he is saying to us, then we understand that Jesus does not demand the same from everyone. Each person has a specific task, to each is assigned a particular way of discipleship. In today’s Gospel, Jesus is speaking directly of the specific vocation of the Twelve, a vocation not shared by the many who accompanied Jesus on his journey to Jerusalem. The Twelve must first of all overcome the scandal of the Cross, and then they must be prepared truly to leave everything behind; they must be prepared to assume the seemingly absurd task of travelling to the ends of the earth and, with their minimal education, proclaiming the Gospel of Jesus Christ to a world filled with claims to erudition and with real or apparent education – and naturally also to the poor and the simple. They must themselves be prepared to suffer martyrdom in the course of their journey into the vast world, and thus to bear witness to the Gospel of the Crucified and Risen Lord. If Jesus’s words on this journey to Jerusalem, on which a great crowd accompanies him, are addressed in the first instance to the Twelve, his call naturally extends beyond the historical moment into all subsequent centuries. He calls people of all times to count exclusively on him, to leave everything else behind, so as to be totally available for him, and hence totally available for others: to create oases of selfless love in a world where so often only power and wealth seem to count for anything. Let us thank the Lord for giving us men and women in every century who have left all else behind for his sake, and have thus become radiant signs of his love. We need only think of people like Benedict and Scholastica, Francis and Clare of Assisi, Elizabeth of Hungary and Hedwig of Silesia, Ignatius of Loyola, Teresa of Avila, and in our own day, Mother Teresa and Padre Pio. With their whole lives, these people have become a living interpretation of Jesus’s teaching, which through their lives becomes close and intelligible to us. Let us ask the Lord to grant to people in our own day the courage to leave everything behind and so to be available to everyone.

Yet if we now turn once more to the Gospel, we realize that the Lord is not speaking merely of a few individuals and their specific task; the essence of what he says applies to everyone. The heart of the matter he expresses elsewhere in these words: “For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake, he will save it. For what does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses or forfeits himself?” (Lk 9:24f.). Whoever wants to keep his life just for himself will lose it. Only by giving ourselves do we receive our life. In other words: only the one who loves discovers life. And love always demands going out of oneself, it always demands leaving oneself. Anyone who looks just to himself, who wants the other only for himself, will lose both himself and the other. Without this profound losing of oneself, there is no life. The restless craving for life, so widespread among people today, leads to the barrenness of a lost life. “Whoever loses his life for my sake … ”, says the Lord: a radical letting-go of our self is only possible if in the process we end up, not by falling into the void, but into the hands of Love eternal. Only the love of God, who loses himself for us and gives himself to us, makes it possible for us also to become free, to let go, and so truly to find life. This is the heart of what the Lord wants to say to us in the seemingly hard words of this Sunday’s Gospel. With his teaching he gives us the certainty that we can build on his love, the love of the incarnate God. Recognition of this is the wisdom of which today’s reading speaks to us. Once again, we find that all the world’s learning profits us nothing unless we learn to live, unless we discover what truly matters in life.

[Pope Benedict, homily Vienna 9 September 2007]

Let us rediscover the place of the Cross in our lives and in society

We adore you O Christ and we praise you, for by your cross you have redeemed the world. Alleluia.

Dear brothers and sisters.

1. As representatives of the people of God in the Archdiocese of Halifax, Cap Breton, all of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, you are gathered in this acclamation of the liturgy with Archbishop Hayes, with the other bishops and with the Church throughout the world. The Catholic Church celebrates today the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross of Christ. As the crucified Christ is lifted up by faith into the hearts of all who believe, so he lifts up those same hearts with a hope that cannot be destroyed. For the cross is the sign of redemption, and in redemption is contained the promise of resurrection and the beginning of new life: the lifting up of human hearts.

At the beginning of my office in the See of St Peter I sought to proclaim this truth with the encyclical Redemptor Hominis. In this same truth I wish today to be united with all of you in adoration of the cross of Christ:

"Do not forget the works of God" (cf. Ps 78:7).

2. To conform ourselves to the acclamation of today's liturgy, let us carefully follow the path traced by these holy words in which the mystery of the Exaltation of the Cross is announced to us.

Firstly, in these words is contained the meaning of the Old Testament. According to St Augustine, the Old Testament contains what is fully revealed in the new. Here we have the image of the bronze serpent to which Jesus referred in his conversation with Nicodemus. The Lord himself revealed the meaning of this image by saying: "And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the son of man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life" (John 3: 14-15).

During the journey of the people of Israel from Egypt to the Promised Land - because the people complained - God sent an invasion of poisonous snakes because of which many perished. When the survivors realised their guilt, they asked Moses to intercede with God: "Pray to the Lord to drive these serpents away from us" (Nm 21:7).

Moses prayed and received this command from the Lord: "Make yourself a snake and put it on a pole. Whoever after being bitten shall look upon it and remain alive" (Nm 21:8). Moses obeyed the order. The bronze snake placed on the pole represented salvation from death for all those who were bitten by snakes.

In the book of Genesis, the serpent was the symbol of the evil spirit. But now, by a surprising inversion, the bronze serpent hoisted in the desert becomes a representation of Christ, hoisted on the cross.

The feast of the Exaltation of the Cross recalls to our minds, and in a way, makes present, the elevation of Christ on the cross. The feast is the elevation of the redeeming Christ: whoever believes in the crucified Christ will have eternal life.

The elevation of Christ on the cross constitutes the beginning of the elevation of humanity through the cross. And the ultimate fulfilment of the elevation is eternal life.

3. This Old Testament event is recalled in the central theme of St John's Gospel.

Why is the cross and the crucified Christ the door to eternal life?

Because in him - in the crucified Christ - God's love for the world, for man, is manifested in its fullness.

In the same conversation with Nicodemus Christ says: "For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. God did not send the Son into the world to judge the world but that the world might be saved through him (Jn 3:16-17).

The salvation of the Son of God through his elevation on the cross has its eternal source in love. It is the love of the Father who sends the Son; he offers his Son for the salvation of the world. At the same time it is the love of the Son who does not 'judge' the world, but sacrifices himself for love of the Father and for the salvation of the world. By giving himself to the Father through the sacrifice of the cross, he offers himself at the same time to the world: to each individual person and to the whole of humanity.

The cross contains within itself the mystery of salvation, because in the cross love is lifted up. This means the elevation of love to the highest point in world history: in the cross, love is sublimated and the cross is at the same time sublimated through love. And from the height of the cross, love descends to us. Yes: "The cross is the deepest stooping of divinity upon man. The cross is like a touch of eternal love on the most painful wounds of man's earthly existence" (Ioannis Pauli PP. II, Dives in Misericordia, 8).

4. To the Gospel of John, the liturgy of today's feast day adds the presentation made by Paul in his letter to the Philippians. The apostle speaks of an emptying of Christ through the cross; and at the same time of the elevation of Christ above all things; and this also had its beginning in the cross itself:

"Jesus Christ . . . stripped himself by assuming the condition of a servant and becoming similar to men, and having appeared in human form, he humbled himself even more by becoming obedient unto death, and death on a cross. For this reason God exalted him and gave him a name that is above every other name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue proclaim that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father" (Phil 2:6-11).

The cross is the sign of Christ's deepest humiliation. In the eyes of the people of that time, it was the sign of an infamous death. Only slaves could be punished with such a death, not free men. Christ, on the other hand, willingly accepts this death, death on the cross. Yet this death becomes the principle of the resurrection. In the resurrection, the crucified servant of Yahweh is lifted up: he is lifted up over all creation.

At the same time, the cross is also lifted up. It ceases to be the sign of an infamous death and becomes the sign of resurrection, that is, of life. Through the sign of the cross, it is not the servant or the slave who speaks, but the Lord of all creation.

5. These three elements of today's liturgy, the Old Testament, the Christological hymn of Paul and the Gospel of John, together form the great richness of the mystery of the triumph of the cross.

As we are immersed in this mystery with the Church, which throughout the world today celebrates the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, I wish to share with you, in a special way, its riches, dear brothers and sisters of the Archdiocese of Halifax, dear people of Nova Scotia, Edward Island and all of Canada.

Yes, I wish to share with you all the riches of that holy cross - which, as the banner of salvation - was planted on your soil 450 years ago. Since then the cross has triumphed in this land and, through the collaboration of thousands of Canadians, the message of deliverance and salvation of the cross has been spread to the ends of the earth.

6. At the same time I wish to pay tribute to the missionary contribution of the sons and daughters of Canada who have given their lives in this way "that the word of the Lord may spread, and be glorified as it is also among you" (2 Thess 3:1). I pay homage to the faith and love that motivated them, and to the power of the cross that gave them the strength to go forth and fulfil Christ's command: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Mt 28:20).

And in paying homage to your missionaries, I likewise pay homage to the communities throughout the world that have welcomed their message and marked their graves with the cross of Christ. The Church is grateful for the hospitality accorded them a burial place, from where they await the final exaltation of the holy cross in the glory of resurrection and eternal life.

I express deep gratitude for the zeal of the Church in Canada and I thank you for your prayers, contributions and various activities through which you support the missionary cause. In particular, I thank you for your generosity towards the Holy See's mission of helping societies.

7. Evangelization remains forever the sacred heritage of Canada, which truly has a glorious history of missionary activity at home and abroad. Evangelisation must continue to be exercised through personal commitment, preaching hope in the promises of Jesus and through the proclamation of fraternal love. It will always be connected with the planting and building of the Church and will have a profound relationship with development and freedom as an expression of human progress. At the heart of this message, however, is an explicit proclamation of salvation in Jesus Christ, that salvation brought about by the cross. Here are the words of Paul VI: "Evangelisation will always contain - even as the basis, centre and summit of its dynamism - a clear proclamation that, in Jesus Christ, the Son of God made man, dead and risen, salvation is offered to every man, as God's own gift of grace and mercy" (Pauli VI, Evangelii Nuntiandi, 27).

The Church in Canada will be itself if it proclaims among all its members, in word and deed, the exaltation of the cross, and if, at home and abroad, it is an evangelising Church.

Although these words come from me, there is another who speaks to the hearts of young people everywhere. It is the Holy Spirit himself, and it is he who presses upon each one of us, as a member of Christ, to lead us to embrace and bring the good news of God's love. But to some the Holy Spirit is proposing the command of Jesus in its specific missionary form: go and recruit disciples from all nations. Before the whole Church, I, John Paul II, once again proclaim the absolute value of the missionary vocation. And I assure all those called to ecclesiastical and religious life that our Lord Jesus Christ is ready to accept and make fruitful the special sacrifice of their lives, in celibacy, for the exaltation of the cross.

8. Today the Church, in proclaiming the Gospel, relives in a certain way the whole period that begins on Ash Wednesday, reaches its climax during Holy Week and at Easter, and continues in the following weeks until Pentecost. The feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross is like the compendium of the entire Paschal Mystery of our Lord Jesus Christ.

The cross is glorious because on it Christ has lifted himself up. Through it, Christ has elevated man. On the cross, every man is truly elevated to his full dignity, to the dignity of his ultimate end in God.

Through the cross, moreover, the power of love is revealed that elevates man, that exalts him.

Truly the whole of God's plan for the Christian life is condensed here in a wonderful way: God's plan and its meaning! Let us adhere to God's plan and its meaning! Let us rediscover the place of the cross in our lives and in our society.

Let us speak of the cross in a special way to all those who suffer, and convey its message of hope to young people. Let us continue to proclaim its saving power to the ends of the earth: "Exaltatio Crucis!": the glory of the holy cross!

Brothers and sisters: "Never forget the works of the Lord"! Amen.

[Pope John Paul II, Homily Halifax (Canada) 14 September 1984]

After concluding the dialogue with the Apostles, Jesus addressed everyone, saying: “If anyone wants to come after me, let him deny himself, take up his cross daily and follow me” (v. 23). This is not an ornamental cross or an ideological cross, but it is the cross of life, the cross of one’s duty, the cross of making sacrifices for others with love — for parents, for children, for the family, for friends, and even for enemies — the cross of being ready to be in solidarity with the poor, to strive for justice and peace. In assuming this attitude, these crosses, we always lose something. We must never forget that “whoever loses his life [for Christ] will save it” (v. 24). It is losing in order to win. Let us remember all of our brothers and sisters who still put these words of Jesus into practice today, offering their time, their work, their efforts and even their lives so as to never deny their faith in Christ. Jesus, through His Holy Spirit, gives us the strength to move forward along the path of faith and of witness: doing exactly what we believe; not saying one thing and doing another. On this path Our Lady is always near to us: let us allow her to hold our hand when we are going through the darkest and most difficult moments.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 19 June 2016]

Trumpets, bass drums and reciters, or perfect instruments

(Mt 6:1-6.16-18)

External wiles have no wisdom: they become a boomerang.

Whoever tries to shine obscures his own light. Anyone who cares about the opinion of the crowds will be a prisoner of it.

Life in the Spirit detaches itself from the practice of (accidental) things to show in order to beg for recognition.

Artificial alms:

Even show men who are starting to lack inspiration like to be considered benefactors of humanity, but their real goal is to go on stage - not the spread of a spirit of disinterest.

They intend to be recognized and acclaimed again - for this they use an absolutely flashy, exhibitionist and tacky way.

Reached the individualistic goal, despite the superficial altruism they would leave everything as it was.

It would be quite different if the left didn’t know what the right does, that is, if every gesture flourished spontaneously and in hiding rather than in overload - but let alone what a pleasure, not to let it be known.

The same orientation is valid for Prayer, much better if inapparent. The inner life is not unnatural acting.

In the Temple the sacrifices were accompanied by public formulas. To this effect, the synagogues were also considered an extension of the Temple. And at the appointed hours, prayer was also on the street.

Those who were able to recite long litanies by heart could thus flaunt their virtue and be admired.

But Dialogue with God is not performance, but essential Listening: root of renewal; principle of criteria and action.

Prayer is intimate perception and profound reading of things. Understanding and empathy that restore us to the meaning of personal life - critical moment of our growth and love for brothers.

The soul dominated by noise doesn’t grasp the guidance of the innate Friend, nor its own primary quality.

Open prayer establishes people in this intimate, secret, hidden atmosphere, which in the Spirit is intertwined with the deepest and most ancestral fibers.

Again, personal prayer is creative. It not only cancels the idea that we have made of life, pains, goals, relationships, defeats, judgments...

[The bitterness doesn’t seem to make life fly - but they invite to move our eyes].

And attentive Listening transmits a new Reading to us; pushes out of boundaries. Puts in contact with other energies and virtues.

A higher level of humanity ‘comes’ to us only in the amazement of this different advice, of an unexpected intuition, of a reality that displaces.

Principle of Liberation that lets our own deep sides meet, and reminds them, making us travel through the akin territory - which we do not yet know.

The woman and the man who gather in prayer are torn from the homologation of interpretative codes, and from the disease of the society of appearances - seated in the opinions and in the time of the minimal.

Finally the (forcibly) thoughtful and undone aspect:

Perhaps even today some use to pose in an extravagant way, showing themselves off as "alternative".

But in this way believers only walk the way of renunciations in a manner [those that God doesn’t ask for]. And to the exact opposite, making the vital wave hysterical.

Instead, we are called to be in company: with ourselves and brothers.

Even renunciation is for harmonious coexistence, without forcing that dissociate the main lines of the personality.

Here too the discernment of spirits becomes a propitious opportunity to create space for the humanizing vocation, and set the time of ambiguous noise in background.

In short, the meaning of imposing Ashes on the heads of the faithful is not one of mortification, but of New Life and revitalisation: as in ancient agricultural practices.

During the cold season, farmers accumulated ashes, and at the end of winter they scattered them on the fields to fertilise them.

Thus, the new meaning of Ashes is understood as fertile flowering.

They do not lead us to Good Friday, but to Easter Sunday.

In a time of renewed discovery of our hidden abilities, and therefore of the freedom to 'descend'.

Recovering everything and everyone to full Life.

In the living and personal Vision, already here and now, of the Risen One.

[Ash Wednesday, February 18, 2026]

Trumpets, bass drums and reciters, or perfect instruments

The faithless lower self, the thespian

Mt 6:1-6.16-18 (.19-23)

"Beware of practising your righteousness before men in order to be admired by them" (Mt 6:1). Jesus, in today's Gospel, reinterprets the three fundamental works of piety in the Mosaic Law. Almsgiving, prayer and fasting characterise the law-abiding Jew. In the course of time, these prescriptions had been marred by the rust of outward formalism, or had even mutated into a sign of superiority. Jesus highlights a common temptation in these three works of piety. When one does something good, almost instinctively the desire arises to be esteemed and admired for the good deed, that is, to have satisfaction. And this, on the one hand, encloses one in oneself, on the other hand, takes one out of oneself, because one lives projected towards what others think of us and admire in us. In re-proposing these prescriptions, the Lord Jesus does not ask for a formal respect to a law that is foreign to man, imposed by a strict legislator as a heavy burden, but invites us to rediscover these three works of piety by living them in a deeper way, not out of self-love, but out of love for God, as means on the path of conversion to Him. Almsgiving, prayer and fasting: this is the path of the divine pedagogy that accompanies us, not only in Lent, towards the encounter with the Risen Lord; a path to be travelled without ostentation, in the certainty that the heavenly Father knows how to read and see even in the secret of our hearts".

[Pope Benedict, homily 9 March 2011].

"But when you pray, enter into your room and shut your door [Is 26:20; 2 Kings 4:33] pray to your Father who is in secret" (Mt 6:6).

The Tao says: "He who attempts to shine, obscures his own Light" and "If you concern yourself with people's opinions, you will be their prisoner".

The disciples are called to a higher righteousness of intention (perfection) than the scribes and Pharisees - who performed according to appearance, public opinion, and retribution.

Jesus does not question religious practices per se, but their purpose and manner.

Aim: [among the still Judaizing veterans, from his communities in Galilee and Syria] to expose the insistents of outward fulfilment.

For shrewdness and the recitation of holiness succeed in fooling the imaginations of many... at least for a time.

But the wiles we are adept at concocting to beg for recognition do not possess the pace of Wisdom.

Fasting, penance and prayer are fundamental works, yet utterly worthless and meaningless if they are not made alive by charity and accompanied by justice.

Life in the Spirit is detached from the practice of 'spiritual' things - to show off... to deceive even oneself.

Finally, the (all incidental) artifice of holy duplicity becomes vague; sooner or later a boomerang.

At that time, the commitment to the Alms was held in high regard, but it had become general practice to announce the most important initiatives - in the synagogue and even in the streets.

For Jesus, publicity affects what belongs to us deeply [let not your left hand know what your right hand is doing] and is honourable.

Even 'devoutly' tightrope walkers, or career politicians who begin to lack the cue, like to make themselves out to be benefactors of humanity. But their real goal is to go on stage - not the spreading of a spirit of selflessness.

They intend to be recognised and acclaimed again - for this they use an absolutely showy, exhibitionist and gaudy manner.

Having reached their true goal of opportunism and individualism, despite their altruistic façade they would drop everything there.

Any convinced fulfilment would have to flourish spontaneously and hidden, instead of in overload - but just imagine what fun it would be, not to let it be known [...].

In reality, renouncing façade propaganda to promote contrary dimensions would extinguish intimate lacerations and conflicts; hidden energies would be released. A more fruitful awareness would be broadened.

The same orientation applies to Prayer, much better if inapparent. The inner life is not unnatural recitation.

Children's prayer is not reduced to a repetition of dirges, nor is it a request for favours; neither is it an exhibitionist and affected catwalk, to be considered pious, 'proper' and 'proper' people.

In the Temple, sacrifices were accompanied by public formulas. To this effect, even the synagogues were considered an extension of the Temple. And at the appointed times, prayers were also said in the streets.

Those who were able to recite long litanies from memory could thus flaunt their virtue and be admired.

But Dialogue with God is not performance, it is essential Listening: the root of renewal; distinguishing criteria and action.

Understanding and empathy, intimate perception and profound intelligence of things restore us to the meaning of personal life - the discriminator of our growth and love for our brothers and sisters.

Why do we thirst for this knowledge, which is only grasped in its exclusive purity in a space of solitude?

Because the soul - overwhelmed with fracas - would not otherwise grasp the guidance of the innate Friend, nor its own essential quality.

There are inescapable questions, beyond the reach of our lower self, i.e. our cerebral or practical activities.

What is our Way? How do we accommodate that which has specific weight and character?

It is not worth solving problems hastily, at all costs, in a conformist or exaggerated manner.

Of course, we do not always get along with God who also wants us to flourish. What is the antidote?

Open prayer establishes people in this intimate, secret, hidden atmosphere that radically belongs to us,

In the Spirit it intertwines with the deepest, ancestral fibres - and gradually brings out the hidden path and destiny.

Personal prayer is creative.

It not only erases our idea of life, of sorrows, of goals, of relationships, of defeats, of judgements...

(Bitterness does not seem to make life fly by - but it does invite the eye to shift).

And Attention Listening gives us a new Reading; it brings us out of the confines. It puts us in touch with other energies and virtues.

A higher level of humanity comes to us only in the amazement of such different advice, of unexpected intuition; of a reality that disorients.

Principle of Liberation that allows us to encounter our own deepest sides, and reminds us of them, leading us into the kindred territory - that we do not yet know.

We must understand deeper than the action-reaction mechanisms allow, filled with distracted tension - absent from our own Calling by Name, which would give us enthusiasm.

Not infrequently, the soul itself - which detests certain outcomes that the society [also ecclesiastical] outside would like to let us live with - revolts, attacks and leads to the failure of all too normal goals.

Even the discomforts come from the simple fact that we are not on the Path of deep attunements: 'point' that bends its contractions towards us, for having chosen the broad but artificial path of compromises.

There are fundamental inclinations for everyone: it would be constructive to yield to them - and to allow ourselves to be guided.

Our complete existence is not a path mapped out by 'where we should go'.

It is appropriate not to be stubborn, and to learn to accommodate the activity of metamorphosis that wants to live; to express itself in us - to guide us and sometimes deviate from 'how we should be'.

The woman and man who gather in prayer are torn from the homologation of interpretative codes, and from the disease of the society of appearance - all sitting in the opinions and time of the minimal.

The same viewpoint for the theme of Fasting: a practice considered a manifestation of conversion to God.

But with surprise we note that Jesus' call applies especially to the religious with a forced pensive and undone air.

Not a few devotees of all creeds use to posture extravagantly - a tawdry expression of their emotional problems.

Indeed, here and there, even in youthful circles, there seems to be some regurgitation of contrived asceticism.

But in this way, believers only tread the path of mannered renunciations [those that God does not ask for], artificial ones. And for the exact opposite, making the life-wave hysterical.

Instead, we are called to be in company: with ourselves and with our brothers. Even renunciation is for the sake of harmonious coexistence, without forcing one's personality lines apart.

Here too, the discernment of spirits becomes a propitious occasion to create space for the humanising vocation.

Already the prophet Isaiah had distinguished between authentic and false fasting [Is 58], that is, not aimed at a life of justice and communion, hence at feasting and joy.

It is useless to undergo practices that do not change the heart.

Along the unspontaneous or trick-or-treat road (of plagiarism suffered or imposed of one's own mind on the soul) the lamb's bleating will sooner or later become a roaring or braying. A matter of time.

In the discernment of the spirits, it is the attitude that reveals the fiction of those who really only think only of power (in greed) and great things, precisely those of megalomaniac superiors, or the elect.

All this using poor Jesus and the little ones, or any creed whatsoever, as screens - just the opposite.

Almsgiving, fasting and prayer are attitudes, not knowable practices outside the unrepeatable language of God himself and his exceptional way of communicating with each person.

Dialogue of an eccentric, precious, ineffable, fantastic, unsurpassed uniqueness, which does not allow itself to be attracted by window-dressing externality, nor by herd-like levelling, or crassness.

Putting the time of ambiguous hubbub in the background.

"Precisely because it is great, my Way seems to be like nothing [...] I do not dare to be first in the world, so I can be chief of the perfect instruments" [Tao Tê Ching, Lxvii].

To internalise and live the message:

Is your spiritual life a time of hubbub ... or a time and fertile ground, a propitious occasion to internalise, to encounter oneself, one's essence, and God in one's brothers and sisters?

Conclusion:

Where is the ecclesial heart?

(Mt 6:19-23)

"Where your treasure is, there your heart will be" (v.21). It is not an abused personal or institutional issue, insipid; from easy ironies.

To ignore it is to give it further breathing space, making it grow out of all proportion; making it even more out of time and difficult to read (and identify its treatment).

All this, however, must be done by putting precipitation in brackets... in the spirit of broader understanding. It is understood that in order to understand each other and activate different resources, each community must go through moments of the most severe verification.

Even for denominational churches with a wide and prestigious tradition, the awareness of being losers in this respect today is indispensable for finding oneself. Overcoming the stumbling block... forwards, 'outwards'.

We read in the Encyclical "Spe Salvi" No. 2 ("Faith is Hope"):

"Hope is a central word in biblical faith - to the point that in several passages the words 'faith' and 'hope' seem interchangeable [...].

How decisive it was for the awareness of the early Christians that they had received a reliable hope as a gift, is also shown where Christian existence is compared with life before faith or with the situation of the followers of other religions [...].

Their gods had proved questionable and no hope emanated from their contradictory myths. Despite the gods, they were 'godless' and consequently found themselves in a dark world, facing a dark future. 'In nihil ab nihilo quam cito recidimus' (In nothing from nothing how soon we fall back) says an epitaph from that era [...].

It appears as a distinctive element of Christians that they have a future: it is not that they know in detail what awaits them, but they know on the whole that their life does not end in a vacuum.

Only when the future is certain as a positive reality does the present also become liveable. So we can now say: Christianity was not just 'good news' - a communication of hitherto unknown content.

In our language we would say: the Christian message was not just 'informative', but 'performative'. This means: the gospel is not just a communication of things that can be known, but a communication that produces facts and changes lives.

The dark door of time, of the future, has been thrown wide open. He who has hope lives differently; he has been given a new life'.

In the form of the Relationship, everything opens up intense life - which integrates and overcomes self-love, the thirst for domination.

This liberates from the 'old', that is, it closes a cycle of paths already set - to make us return as newborns.

The Hope that has weight dismantles the inessential; it expels the noise of thoughts that are no longer in tune with our growth, and introduces dreamy energies, a wealth of possibilities.

There will be initial resistance, but development sets in.

Hope sacrifices ballasts and activates us according to the 'divine within'. It opens the door to a new, brighter and corresponding phase.

The treasures of the earth quickly blind; likewise they pass away: suddenly. The age of global crisis throws it in our faces.

Yet, it is a necessary pain.

We understand: the new paths are not traced by goods, nor by devout memories, but by the Void, which acts as a gap to common, taken for granted, reassuring easiness.

Religiosity good for all seasons gives way to the unprecedented life of Faith.

This is where the Art of discernment and pastoral work comes in: it should know how to introduce new competitive, dissimilar energies - cosmic and personal - that prepare unprecedented, open, gratuitous syntheses.

We know this, and yet in some circles (prestigious and already wealthy) the greed to possess under the guise of necessity does not allow them to see clearly.

It happens even to long-standing consecrated persons - it is not clear why such greedy, perfunctory duplicity.

Do we still want to emerge, raising more confusions? After all, we are dissatisfied with our mediocre choices.

At the beginning of the Vocation, we felt the need for a Relationship that would bring Meaning and a Centre to our feriality...

Then we deviated, perhaps out of dissatisfaction or for reasons of calculation and convenience - and the dullness of our robbing eyes prevailed. First here and there, gradually occupying the soul.

Even in some leaders and prominent church circles, the basis of existence has become the many-zero bank account.

So... the vanity scene, the bag of commerce, the thrill of getting on the board, in various realities have supplanted real hearts - and eyes themselves.

As if to say: there is another experience of the 'divine', which is a doomsday: between one Psalm and another, better than Love becomes feeling powerful, secure and respected around.

(Do God and accumulation give different orders? No problem: let it be understood that one does it for 'his' Glory).

So much for the common good.

Not a few people are realising that counting is the most popular sport in various multi-pious companies, fantastically embellished with events and initiatives (to cover what it's worth).

And litmus test is precisely that mean-spirited scrutiny (vv.22-23) that behind dense scenes, holds back, even judges, and keeps a distance from others. With the gaze that closes the horizon of existence: the immediately at hand, and of circumstance, counts.

A seemingly superabundant belief - coincidentally without the prominence of Hope - is condemning us to the world's worst denatality rate.

The panorama of our devoutly empty villages and towns is discouraging. But one revels in one's own niche, and in the petty situation.

The important thing is that everything is epidermically adorned.

Under the peculiar bell tower that sets the pace for the usual things, many people keep 'their' (too much) to themselves, content to sacralise selfishness with the display of beautiful statues, customs, banners, colourful costumes and mannerisms.

Instead, according to the Gospels, in the attempts and paths of Faith that are not satisfied with an empty spirituality, life becomes bright with creative Love that flourishes, and puts everyone at ease.

Even the old can re-emerge in this new spirit. For there are other Heights. For what makes one intimate with God is nothing external.

The authentic Church aroused by clear 'visions' - without papier-mâché and duplicity - always reveals something portentous: fruitfulness from nullity, life from the outpouring of it, birth from apparent sterility.

A river of unimagined attunements will reconnect the reading of events and the action of believers to the work of the Spirit, without barriers.

For when normalised thinking gives way and settles down, the new advances.

The choice is now inexorable: between death and life; between longing and "darkness" (v.23), or Happiness.

The first step is to admit that one has to make a path.

To internalise and live the message:

Where is your treasure? Are your heart and your eye simple?

Have you ever experienced aspects that others judge inconclusive (from a material point of view) but which have instead paved the way for your new paths?

Ashes without mortification

In short, the meaning of imposing ashes on the heads of the faithful is not one of mortification, but of New Life and vivification: as in ancient agricultural practices.

In fact, during the cold season, farmers accumulated ashes, and at the end of winter they spread them on the fields to fertilise them.

Thus, the new meaning of ashes is understood as fruitful flowering.

They do not want to lead us to Good Friday, but to Easter Resurrection.

In a time of renewed discovery of our hidden abilities, and therefore of the freedom to 'descend'.

Recovering everything and everyone to full Life.

In the living and personal Vision, already here and now, of the Risen One.

St John Chrysostom urged: “Embellish your house with modesty and humility with the practice of prayer. Make your dwelling place shine with the light of justice; adorn its walls with good works, like a lustre of pure gold, and replace walls and precious stones with faith and supernatural magnanimity, putting prayer above all other things, high up in the gables, to give the whole complex decorum. You will thus prepare a worthy dwelling place for the Lord, you will welcome him in a splendid palace. He will grant you to transform your soul into a temple of his presence” (Pope Benedict)

San Giovanni Crisostomo esorta: “Abbellisci la tua casa di modestia e umiltà con la pratica della preghiera. Rendi splendida la tua abitazione con la luce della giustizia; orna le sue pareti con le opere buone come di una patina di oro puro e al posto dei muri e delle pietre preziose colloca la fede e la soprannaturale magnanimità, ponendo sopra ogni cosa, in alto sul fastigio, la preghiera a decoro di tutto il complesso. Così prepari per il Signore una degna dimora, così lo accogli in splendida reggia. Egli ti concederà di trasformare la tua anima in tempio della sua presenza” (Papa Benedetto)

And He continues: «Think of salvation, of what God has done for us, and choose well!». But the disciples "did not understand why the heart was hardened by this passion, by this wickedness of arguing among themselves and seeing who was guilty of that forgetfulness of the bread" (Pope Francis)

E continua: «Pensate alla salvezza, a quello che anche Dio ha fatto per noi, e scegliete bene!». Ma i discepoli «non capivano perché il cuore era indurito per questa passione, per questa malvagità di discutere fra loro e vedere chi era il colpevole di quella dimenticanza del pane» (Papa Francesco)

[Faith] is the lifelong companion that makes it possible to perceive, ever anew, the marvels that God works for us. Intent on gathering the signs of the times in the present of history […] (Pope Benedict, Porta Fidei n.15)

[La Fede] è compagna di vita che permette di percepire con sguardo sempre nuovo le meraviglie che Dio compie per noi. Intenta a cogliere i segni dei tempi nell’oggi della storia […] (Papa Benedetto, Porta Fidei n.15)

But what do this “fullness” of Christ’s Law and this “superior” justice that he demands consist in? Jesus explains it with a series of antitheses between the old commandments and his new way of propounding them (Pope Benedict)

Ma in che cosa consiste questa “pienezza” della Legge di Cristo, e questa “superiore” giustizia che Egli esige? Gesù lo spiega mediante una serie di antitesi tra i comandamenti antichi e il suo modo di riproporli (Papa Benedetto)

The Cross is the sign of the deepest humiliation of Christ. In the eyes of the people of that time it was the sign of an infamous death. Free men could not be punished with such a death, only slaves, Christ willingly accepts this death, death on the Cross. Yet this death becomes the beginning of the Resurrection. In the Resurrection the crucified Servant of Yahweh is lifted up: he is lifted up before the whole of creation (Pope John Paul II)

La croce è il segno della più profonda umiliazione di Cristo. Agli occhi del popolo di quel tempo costituiva il segno di una morte infamante. Solo gli schiavi potevano essere puniti con una morte simile, non gli uomini liberi. Cristo, invece, accetta volentieri questa morte, la morte sulla croce. Eppure questa morte diviene il principio della risurrezione. Nella risurrezione il servo crocifisso di Jahvè viene innalzato: egli viene innalzato su tutto il creato (Papa Giovanni Paolo II)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.