1. We profess our faith in the central truth of the messianic mission of Jesus Christ: he is the redeemer of the world through his death on the cross. We profess it in the words of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, according to which Jesus 'was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, died and was buried'. In professing this faith, we also commemorate Christ's death as a historical event, which, like his life, is known to us from reliable and authoritative historical sources. Based on these same sources we can and will also know and understand the historical circumstances of that death, which we believe was "the price" of man's redemption for all time.

2. And first of all: how did the death of Jesus of Nazareth come about? How do we explain the fact that he was put to death by the representatives of his nation, who handed him over to the Roman 'procurator', whose name, transmitted from the Gospels, also appears in the Symbols of Faith? For now, let us try to gather the circumstances, which 'humanly' explain the death of Jesus. The evangelist Mark, describing Jesus' trial before Pontius Pilate, notes that he had been 'delivered up for envy' and that Pilate was aware of this fact: 'He knew . . . that the high priests had delivered him up for envy' (Mk 15:10). Let us ask ourselves: why this envy? We can find its roots in resentment not only for what Jesus taught, but for the way he did it. If, according to Mark, he taught "as one having authority, and not as the scribes" (Mk 1:22), this circumstance must have shown him in the eyes of the latter as a "threat" to their own prestige.

3. In fact, we know that already the beginning of Jesus' teaching in his hometown leads to conflict. The thirty-year-old Nazarene, in fact, when speaking in the synagogue, points to himself as the one on whom the announcement of the Messiah, pronounced by Isaiah, is fulfilled. This provokes astonishment and later indignation in the hearers, so that they want to throw him down from the mountain 'on which their city was situated' . . . "but he passed by among them and went away" (Lk 4:29-30).

4. This incident is only the beginning: it is the first sign of subsequent hostilities. Let us recall the main ones. When Jesus makes it clear that he has the power to forgive sins, the scribes see this as blasphemy, because only God has such power (cf. Mk 2:6). When he performs the miracles on the Sabbath, asserting that "the Son of Man is Lord of the Sabbath" (Mt 12:8), the reaction is similar to the previous one. And it is already then that the intention to kill Jesus transpires (cf. Mk 3:6): "They sought . . . to kill him: because he not only violated the Sabbath, but called God his Father, making himself equal with God" (Jn 5:18). What else could the words "Verily, verily, I say unto you, before Abraham was I Am" mean? (Jn 8:58). The listeners knew what that designation meant: "I Am". So again Jesus runs the risk of stoning. This time, however, he ". . . he hid himself and went out of the temple" (Jn 8:59).

5. The event that ultimately precipitated the situation and led to the decision to let Jesus die was the resurrection of Lazarus in Bethany. The Gospel of John lets us know that at the next meeting of the Sanhedrin it was noted: 'This man performs many signs. If we let him do this, everyone will believe in him and the Romans will come and destroy our holy place and our nation". Faced with these predictions and fears Caiaphas, the high priest, pronounced this sentence: 'Better that one man should die for the people and not the whole nation perish' (Jn 11:47-50). The evangelist adds: 'This, however, he did not say for himself, but being high priest he prophesied that Jesus should die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but also to gather together the children of God who were scattered'. And he concludes: "From that day therefore they decided to kill him" (John 11: 51-53).

John lets us know in this way a twofold aspect of Caiaphas' stance. From a human point of view, which more accurately could be said to be opportunistic, it was an attempt to justify the decision to eliminate a man deemed politically dangerous, without worrying about his innocence. From a higher point of view, made his own and noted by the evangelist, Caiaphas' words, regardless of his intentions, had an authentically prophetic content, concerning the mystery of Christ's death according to God's saving plan.

6. Here we consider the human unfolding of events. At that meeting of the Sanhedrin, the decision was made to kill Jesus of Nazareth. They took advantage of his presence in Jerusalem during the Passover festivities.Judas, one of the twelve, betrayed Jesus for thirty silver coins, pointing to the place where he could be arrested. Once taken, Jesus was brought before the sanhedrin. To the high priest's essential question: "I beseech thee by the living God, that he may tell us whether thou art the Christ, the Son of God", Jesus gave the great answer: "Thou hast said it" (Matt 26:63-64; cf. Mk 14:62; Lk 22:70). In this declaration the Sanhedrin saw blatant blasphemy, and ruled that Jesus was "guilty of death!" (Mk 14:64).

7. However, the sanhedrin could not carry out the sentence without the consent of the Roman procurator. And Pilate is personally convinced that Jesus is innocent, and he makes this clear several times. After uncertainly resisting the pressure of the Sanhedrin, he finally relents for fear of risking Caesar's disapproval, all the more so since the crowd, stirred up by the proponents of Jesus' elimination, now also demands his crucifixion. "Crucifige eum!" And so Jesus is condemned to death by crucifixion.

8. Historically responsible for this death are the men indicated in the Gospels, at least in part, by name. Jesus himself declares this when he says to Pilate during the trial: "He who delivered me into your hands has a greater guilt" (John 19:11). And in another passage; "The Son of Man goes, as it is written of him, but woe to that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed! Better for that man if he had never been born!" (Mk 14:21; Mt 26:24; Lk 22:22). Jesus alludes to the various people who, in different ways, will be the architects of his death: to Judas, to the representatives of the Sanhedrin, to Pilate, to others . . . Even Simon Peter, in his speech after Pentecost, disputes the killing of Jesus to the leaders of the Sanhedrin: "You nailed him to the cross by the hands of ungodly men and killed him" (Acts 2:23).

9. However, one cannot extend this imputation beyond the circle of the truly responsible persons. We read in a document of the Second Vatican Council: 'If Jewish authorities with their followers worked for the death of Christ, nevertheless what was committed during his passion cannot be imputed either indiscriminately to all the Jews then living, or (even less) to the Jews of our time' (Nostra Aetate, 4).

When it comes to assessing the responsibility of consciences, we cannot forget Christ's words on the cross: "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do" (Lk 23:34). We find an echo of those words in another speech by Peter after Pentecost: "Now, brothers, I know that you acted in ignorance, as did your leaders" (Acts 3:17). What a sense of reserve before the mystery of the human conscience, even in the case of the greatest crime committed in history, the killing of Christ!

10. Following the example of Jesus and Peter, even though it is difficult to deny the responsibility of those men who deliberately caused Christ's death, we too will look at things in the light of God's eternal plan, which required his beloved Son to offer himself as a victim for the sins of all men. In this higher perspective we realise that we are all, by reason of our sins, responsible for Christ's death on the cross: all, insofar as through sin we have contributed to Christ dying for us as a victim of atonement. Jesus' words can also be understood in this sense: "The Son of Man is about to be delivered into the hands of men, and they will kill him, but on the third day he will rise" (Matthew 17: 22).

11. The cross of Christ is thus for all a realistic reminder of the fact expressed by the Apostle John in the words: "The blood of Jesus, his Son, cleanses us from all sin. If we say that we are without sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us" (1 John 1: 7-8). The cross of Christ does not cease to be for each of us this merciful and at the same time severe call to acknowledge and confess our guilt. It is a call to live in truth.

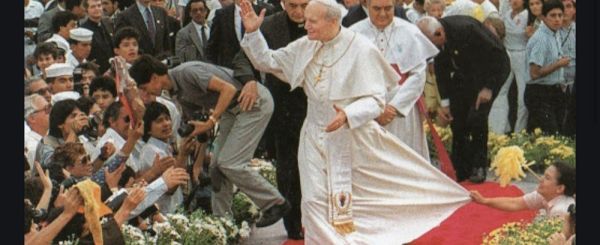

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 28 September 1988]