14. Jesus enters into the concrete and historical situation of women, a situation which is weighed down by the inheritance of sin. One of the ways in which this inheritance is expressed is habitual discrimination against women in favour of men. This inheritance is rooted within women too. From this point of view the episode of the woman "caught in adultery" (cf. Jn 8:3-11) is particularly eloquent. In the end Jesus says to her: "Do not sin again", but first he evokes an awareness of sin in the men who accuse her in order to stone her, thereby revealing his profound capacity to see human consciences and actions in their true light. Jesus seems to say to the accusers: Is not this woman, for all her sin, above all a confirmation of your own transgressions, of your "male" injustice, your misdeeds?

This truth is valid for the whole human race. The episode recorded in the Gospel of John is repeated in countless similar situations in every period of history. A woman is left alone, exposed to public opinion with "her sin", while behind "her" sin there lurks a man - a sinner, guilty "of the other's sin", indeed equally responsible for it. And yet his sin escapes notice, it is passed over in silence: he does not appear to be responsible for "the others's sin"! Sometimes, forgetting his own sin, he even makes himself the accuser, as in the case described. How often, in a similar way, the woman pays for her own sin (maybe it is she, in some cases, who is guilty of the "others's sin" - the sin of the man), but she alone pays and she pays all alone! How often is she abandoned with her pregnancy, when the man, the child's father, is unwilling to accept responsibility for it? And besides the many "unwed mothers" in our society, we also must consider all those who, as a result of various pressures, even on the part of the guilty man, very often "get rid of" the child before it is born. "They get rid of it": but at what price? Public opinion today tries in various ways to "abolish" the evil of this sin. Normally a woman's conscience does not let her forget that she has taken the life of her own child, for she cannot destroy that readiness to accept life which marks her "ethos" from the "beginning".

The attitude of Jesus in the episode described in John 8:3-11 is significant. This is one of the few instances in which his power - the power of truth - is so clearly manifested with regard to human consciences. Jesus is calm, collected and thoughtful. As in the conversation with the Pharisees (cf. Mt 19:3-9), is Jesus not aware of being in contact with the mystery of the "beginning", when man was created male and female, and the woman was entrusted to the man with her feminine distinctiveness, and with her potential for motherhood? The man was also entrusted by the Creator to the woman - they were entrusted to each other as persons made in the image and likeness of God himself. This entrusting is the test of love, spousal love. In order to become "a sincere gift" to one another, each of them has to feel responsible for the gift. This test is meant for both of them - man and woman - from the "beginning". After original sin, contrary forces are at work in man and woman as a result of the threefold concupiscence, the "stimulus of sin". They act from deep within the human being. Thus Jesus will say in the Sermon on the Mount: "Every one who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart" (Mt 5:28). These words, addressed directly to man, show the fundamental truth of his responsibility vis-a-vis woman: her dignity, her motherhood, her vocation. But indirectly these words concern the woman. Christ did everything possible to ensure that - in the context of the customs and social relationships of that time - women would find in his teaching and actions their own subjectivity and dignity. On the basis of the eternal "unity of the two", this dignity directly depends on woman herself, as a subject responsible for herself, and at the same time it is "given as a task" to man. Christ logically appeals to man's responsibility. In the present meditation on women's dignity and vocation, it is necessary that we refer to the context which we find in the Gospel. The dignity and the vocation of women - as well as those of men - find their eternal source in the heart of God. And in the temporal conditions of human existence, they are closely connected with the "unity of the two". Consequently each man must look within himself to see whether she who was entrusted to him as a sister in humanity, as a spouse, has not become in his heart an object of adultery; to see whether she who, in different ways, is the cosubject of his existence in the world, has not become for him an "object": an object of pleasure, of exploitation.

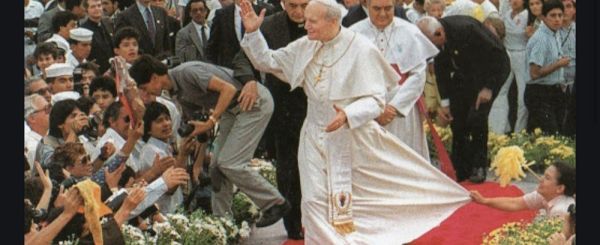

[Pope John Paul II, Mulieris Dignitatem]