But that victory opened, for John Paul II, another front, no less important and no less heartfelt, in which indeed he lavished enormous energy and which he made the subject of constant pastoral and doctrinal reminders. It is the fear, for him rather an awareness, that after the end of communism, a combination of democracy and cultural relativism, the fruit of a consumerist and materialist society, could be born in the countries of successful capitalism. In John Paul II's largely prophetic analysis, this alliance would produce a tragic loss of identity due to secularisation and the disappearance of the religious dimension from the conscience of individuals and the collective behaviour of civil societies.

In his most committed social encyclical, the Centesimus Annus of 1 May 1991, it is very clear that the mixture of freedom without truth appeared explosive and fatal to Pope Wojtyla. From this awareness arose or sharpened in him a tenacious mistrust of modernity, its pressure, its demands, its secularist mechanisms and automatisms. And this diffidence strengthened in him the decisive rejection of the compromises that modernity requires or imposes on the believer, especially on that believer who had thought of accepting the logic of modernity, as the Second Vatican Council and, after the Council, many of those clergy and believers who demanded a more democratic, more liberal Church, more in tune with the times.

But being in tune with modern times was not a siren call for John Paul II. To the danger of relativism he opposed Christianity as a strong thought, truth as an antidote to scepticism, faith as a defence against nihilism, as shown by two documents that not a little divided consciences and not a little brought the Pope the accusation of dogmatism or conservatism or pre-conciliar restoration. One is the encyclical Redemptoris missio of 7 December 1990, which speaks of "Jesus Christ the only saviour", the other is the Declaration Dominus Iesus of 6 August 2000, which declares "contrary to the faith of the Church the thesis regarding the limited, incomplete and imperfect character of the revelation of Jesus Christ".

Also from the fear of the alliance between democracy and relativism came Pope Wojtyla's intransigent positions on two fundamental issues.

The first issue is that of identity, in particular European identity, which John Paul II never stopped tracing back to its Christian roots and for whose recognition, even formal, within the new constitution of Europe he fought without retreat. In the face of the Europe of markets and rights, he claimed the Europe of values and spirit, that of the apostles Peter and Paul, and of the saints and martyrs Cyril and Methodius, who carried out the same work of Christianisation in the East of the continent that the former brought to the West. It was the Europe of the 'two lungs', the Europe spiritually unified and not just politically enlarged.

The second issue is that of the recognition of the dignity of the person in any manifestation and phase of existence, from which sprang his firm and unhesitating condemnation of every form of disrespect for man, from abortion to euthanasia, from contraception to artificial insemination, from genetic experimentation to embryo research. John Paul II, the same one who had asked 'pardon' for the Church's errors in the Galileo case, but who had never embraced the scientist principle of the complete autonomy of scientific research, rejected the idea and practice of the limitlessness of the boundaries of bioethics, which instead must stop where it clashes with respect for human life and dignity. The battle against cultural relativism also marks a moment of tension or rethinking in the work of John Paul II. He had been the initiator of the inter-religious dialogue project, the aim of which was to unite the three great monotheistic religions under the common banner of spirituality in order to enhance their points of contact and strengthen their mission. But this very dialogue, by its very logic, risked running the risk of cultural relativism.

The problem is well known and terribly intricate. Dialogue assumes that the truth of one can be exchanged or corrected for the truth of the other. Therefore, dialogue rejects absoluteness and admits reciprocity of positions. But, then, if dialogue is practised, how can Christ be said to be the only truth and therefore the absolute truth? And conversely, if Christ is the only truth, on what basis, beyond that of personal respect for the interlocutors, is dialogue possible?

Right in the midst of rampant relativism, John Paul II was faced with this distressing dilemma. He could not reject interreligious dialogue, which was part of his conception and action, and he could not run the risk that this dialogue would shake the foundations of the Christian faith.

The fight against cultural relativism marked another tension in the work of John Paul II, especially in recent years, when global changes have accelerated dramatically and the evil of a new totalitarianism, that of Islamic fundamentalism responsible for 9/11, has again loomed in history. In the face of this tragic event and its consequences, Pope Wojtyla chose the strong position of taking sides on the front of peace and also pacifism, against war and resolutely against the hypothesis of a clash of civilisations. This was also a tension, because to affirm the good and bring peace it is sometimes necessary to fight against evil, as John Paul II knew first hand, he son of a martyred land, a constant victim of aggression and oppression, the last of which were the Nazis and the Communists.

I have spoken of tensions, others have said of contradictions and taken critical, even harshly critical positions in the face of what seemed to be the 'closures' of John Paul II. But for those who understand the meaning of faith, criticism is definitely out of place. Contradiction is the spirit of the Gospel, it is the essence of Christianity, which is in the world in order to give the world a meaning that is outside the world, which lives the historical condition in order to redeem it, not to accommodate or lie down in it. The theological and pastoral problems provoked by these tensions, always essential and never avoidable, will be the heritage and the challenge of whoever succeeds John Paul II. With history back in motion, evil returning, and a new demand for religious identity pressing in, he will need firm and clear vision, firmness and gentleness, tenacity and openness. Those same qualities to which Pope Wojtyla was a tireless witness during his 27 years of pontificate.

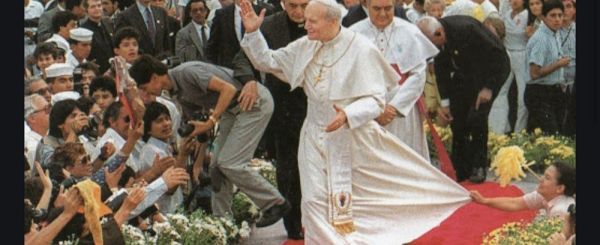

[Pope John Paul II, Address to the Senate 5 April 2005; website commentary]