don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Salt and Light: Beautiful Works. Vocation and salt gone mad

4th Sunday in O.T.

Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time (year A) [1 February 2026]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. Rereading and meditating on the Beatitudes in Matthew's Gospel is always an invitation to rediscover the heart of the Gospel faith and to have the courage to live it faithfully.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Zephaniah (2:3; 3:12-13)

The Book of Zephaniah is striking for its sharp contrasts: on the one hand, there are terrible threats against Jerusalem, with the prophet appearing very angry; on the other hand, there are encouragements and promises of a happy future, always directed at the city. The question is: to whom are the threats addressed and to whom the encouragement? Historically, we are in the 7th century BC, in the kingdom of Judah, the southern kingdom. The young king Josiah ascends the throne at the age of eight, after the assassination of his father, in very turbulent times. The Assyrian empire, with its capital at Nineveh, is expanding, and local kings often prefer to surrender to avoid destruction: Jerusalem becomes a vassal of Nineveh. The prophets, however, firmly support the freedom of the chosen people: asking for an alliance with an earthly king means not trusting in the King of heaven. Accepting Assyrian protection was not only a political act, but also entailed the cultural and religious influence of the ruler, with the risk of idolatry and the loss of Israel's mission. Zephaniah denounced all this and prophesied punishment: 'I will raise my hand against Judah and against all the inhabitants of Jerusalem... on the day of the Lord's wrath' (Zephaniah 1:4-6), a text reminiscent of the famous Dies Irae. Seek the Lord, all you humble of the land. Alongside the threats, Zephaniah addresses a message of comfort to the "humble of the land" (in Hebrew anawim, the bowed down), who are law-abiding and righteous, and therefore protected from the Day of the Lord's wrath: God himself is with them. It is the day when creation will be renewed and evil destroyed. The message is not for others, but for each one of us: we are all called to conversion, to become "the humble of the land," the "Remnant of Israel" that the previous prophets had announced. God, who is faithful, will always save at least a small group that has remained faithful. It will be this small remnant, poor and humble, that will carry on the mission of the chosen people: to reveal God's plan to the world. Being humble means recognising one's own limitations (humus) and trusting totally in God. Thus, God's judgement is not against people, but against the evil that corrupts. The small faithful remnant will be the leaven in the world, preserving the true identity of the people and the divine mission. God's wrath strikes only evil, never the innocent. Zephaniah also criticises the adoption of Assyrian customs, such as foreign clothing (Zeph 1:8): it was not just fashion, but a sign of imitation of the pagans, a risk of losing identity and faith.

*Responsorial Psalm (145/146)

Here we have three verses from the Psalm as an inventory of the beneficiaries of God's mercy: the oppressed, the hungry, the chained, the blind, the afflicted, the strangers, the widows and the orphans—all those whom men ignore or despise. The Israelites know these situations because they have experienced them: oppression in Egypt, then in Babylon. The Psalm was written after the return from the Babylonian exile, perhaps for the dedication of the rebuilt Temple. Liberation from evil and oppression is perceived as proof of God's faithfulness to the covenant: "The Lord brings justice to the oppressed, the Lord frees those in chains." God also provides for material needs: during the Exodus, he fed the people with manna and quails. Gradually, God reveals himself to the blind, lifts up the afflicted and guides the people towards justice: 'God loves the righteous'. The Psalm is therefore a song of gratitude: "The Lord brings justice to the oppressed / gives bread to the hungry / frees those in chains / opens the eyes of the blind / lifts up those who are afflicted / loves the righteous / protects the stranger / supports widows and orphans. The Lord is your God forever." The insistence on the name Lord (7 times) recalls the sacred Tetragrammaton YHVH, revealed to Moses at the burning bush, symbol of God's constant and liberating presence. "The Lord is your God forever," the final phrase recalls the Covenant: "You shall be my people, and I will be your God." The Psalm looks to the future, strengthening the hope of the people. The name of God Ehiè asher ehiè (I am who I am / I will be who I will be) emphasises his eternal presence. Repeating this Psalm serves to recognise God's work and to guide conduct: if God has acted in this way towards Israel, the people must behave in the same way towards others, especially the excluded. The Law of Israel provided rules to protect widows, orphans, and foreigners, so that the people would be free and respectful of the freedom of others. The prophets judged fidelity to the Covenant mainly on the basis of attitude towards the poor and oppressed: the fight against idolatry, the promotion of justice and mercy, as in Hos 6:6 (I desire mercy, not sacrifice) and Mic 6:8 (Act justly, love mercy, walk humbly with God). Sirach also reminds us: 'The tears of the widow flow down the face of God' (Si 35:18), emphasising that those who are close to God must feel compassion for those who suffer.

*Second Reading from the First Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Corinthians (1:26-31).

It would seem to be the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector: the world is 'turned upside down'. Those who appear wise in the eyes of men, as Paul points out, are not considered worthy before God. This does not mean that Paul despises wisdom: since the time of King Solomon, it has been a virtue sought after in prayer, and Isaiah presents it as a gift of the Spirit of God: 'The Spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him, the spirit of wisdom and discernment...' The Bible distinguishes between two types of wisdom: the wisdom of men and the wisdom of God. What seems reasonable in the eyes of men may be far from God's plan, and what is wise in the eyes of God may appear foolish to men. Our logic is human, God's is the logic of love: the folly of divine love, as Paul says, surpasses all human reasoning. This is why the life and death of Christ may seem scandalous. Isaiah says it clearly: "My thoughts are not your thoughts, and your ways are not my ways" (Is 55:8). This distance between human and divine thought is such that Jesus goes so far as to rebuke Peter: "Get behind me, Satan! You are not thinking according to God, but according to men" (Mt 16:23). God is the "All-Other": the hierarchy of human values is overturned before him. Often in the history of the Covenant, God chooses the least: think of David, the youngest of Jesse's sons, or the people of Israel, "the least of all" (Deut 7:7; Deut 9:6). God's choices are gratuitous, independent of human merit. True wisdom, divine wisdom, is a gift from We cannot understand God with our own strength: everything we know about Him is revealed to us by Him. Paul reminds the Corinthians that all knowledge of God is a gift: "In him you have received every spiritual blessing... you are not lacking in any spiritual gift" (1 Cor 1:4-7). The gift of knowledge of God is not a reason for pride, but for gratitude. As Jeremiah says: "Let not the wise man boast of his wisdom... but of having the intelligence to know me, the Lord" (Jer 9:22-23). Paul applies these principles to the Corinthians: in the eyes of the world, they were neither wise, nor powerful, nor noble. Yet God calls them, creating his Church out of their poverty and weakness. Their 'nobility' is Baptism. Corinth becomes an example of God's surprising initiative, recreating the world according to his logic, inviting men not to boast before God, but to give him glory for his love.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (5:1-12a)

I pause to reflect on the beatitude that may seem most difficult: 'Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted' (Mt 5:4). It is not a question of rejoicing in mourning itself, nor of considering suffering as good fortune. Jesus himself devoted much of his life to comforting, healing and encouraging people: Matthew reminds us that 'Jesus proclaimed the Good News of the Kingdom and healed every disease and infirmity among the people' (Mt 4:23). The tears Jesus speaks of are, rather, tears of repentance and tears of compassion. Think of St Peter, who wept bitterly after his denial, finding consolation in God's mercy. Or remember the vision of the prophet Ezekiel: on the last day, God "will mark with a cross on the forehead those who groan and lament over the abominations that are committed" (Ezekiel 9:4). These words of Jesus were addressed to his Jewish contemporaries, who were accustomed to the preaching of the prophets. For us, understanding them means rereading the Old Testament. As the prophet Zephaniah invites us: 'Seek the Lord, all you humble of the earth' (Zeph 2:3). And the psalm sings: “I have asked one thing of the Lord: to dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life” (Ps 145/146:5). These are the true “poor in spirit,” those who entrust themselves completely to God, like the tax collector in the parable: aware of their sins, they open themselves to the Lord’s salvation. Jesus assures us that those who seek God with all their heart will be heard: "Seek and you will find; knock and it will be opened to you" (Mt 7:7). And the prophets call those whose hearts are turned solely to God "pure". The Beatitudes, therefore, are Good News: it is not power, knowledge or wealth that leads us to the Kingdom, but gentleness, mercy and justice. As Jesus says to his disciples: " I am sending you out like lambs among wolves” (Lk 10:3). Each beatitude points to a path towards the Kingdom: each “Blessed” is an invitation, an encouragement: it is as if it were saying, “take courage, you are on the right path”. Our weaknesses become fertile ground for God’s presence: poverty of heart, tears, hunger for justice, persecution. Paul reminds us: “Let the one who boasts, boast in the Lord” (1 Cor 1:31). Finally, let us remember that Jesus is the perfect model: poor in heart, gentle, merciful, compassionate, just and persecuted, always grateful to the Father. His life teaches us to look at ourselves and others through the eyes of God, and to discover the Kingdom where we least expect it.

St Augustine writes in his commentary on this beatitude: "Blessed, says the Lord, are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. He does not refer to bodily sadness, but to the sorrow of the heart for sins and the desire to convert to God" (Enarrationes in Psalmos, 30:5).

+Giovanni D'Ercole

3rd Sunday in O.T.

Third Sunday in Ordinary Time (Year A) [25 January 2026]

May God bless us and may the Virgin Mary protect us! Today marks the end of the week of prayer for Christian unity. The word of God offers food for thought, especially the second reading (which recounts the situation of the community in Corinth with divisions due to the presence of various preachers).

The Gospel shows the beginning of Jesus' preaching with his disciples, who will accompany him all the way to Jerusalem.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (8:23b - 9:3)

At the time of Isaiah, the kingdom of Israel was divided into two: the North (Israel, capital Samaria) and the South (Judah, capital Jerusalem), the latter being legitimate as heir to the dynasty of David. Isaiah preaches in Jerusalem but speaks mainly of places in the North, such as Zebulun, Naphtali, Galilee and Transjordan, territories that were conquered by the Assyrian Empire between 732 and 721 BC. The prophet announces that God will transform the situation: the regions that were initially humiliated will be honoured, as a sign of liberation and rebirth. These promises also concern the south, because geographical proximity means that threats to one area weigh on the other, and because the south hopes for future reunification under its own leadership. Isaiah describes the birth of a king, associating his coming with royal coronation formulas: 'A child has been born to us, a son has been given to us' (Isaiah 9:5-6). This is the young Hezekiah, associated with the reign of his father, King Ahaz, and considered the 'prince of peace'. The prophet's certainty is based on God's faithfulness: even in trials and oppression, God will never abandon the dynasty of David. The promised victory recalls that of Gideon over the Midianites: even with few resources, faith in God leads to liberation. The final message is one of hope: do not be afraid, God does not abandon his plan of love for humanity, even in the darkest moments.

*Responsorial Psalm (26/(27)

"The Lord is my light and my salvation" is not just an individual expression: it reflects the invincible trust of the people of Israel in God, in every circumstance of life, from joys to difficulties. The psalm uses concrete images to tell the collective story of Israel, a frequent procedure in the Psalms called clothing: the people are compared to a sick person healed by God, to an innocent person unjustly condemned, to an abandoned child or to a besieged king. Behind these individual images, we recognise specific historical situations: external threats, sieges of cities and internal crises of the kingdom, such as the attack of the Amalekites in the desert, the kings of Samaria and Damascus against Ahaz, or the famous siege of Jerusalem by Sennacherib. The people can react like David, a normal and sinful man, but steadfast in his faith, or like Ahaz, who gives in to panic and loses his trust in God. In any case, the psalm shows that collective faith is nourished by trust in God and the memory of his works. Another key image is that of the Levite, servant of the Temple: just as the Levites serve God daily, so the whole people of Israel is consecrated to the service of the Lord and belongs to him. Finally, the psalm ends with a promise of hope: 'I am sure that I shall see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living'; trust is rooted in the memory of God's actions and translates into courage and active hope: 'Hope in the Lord, be strong, strengthen your heart and hope in the Lord'. This hope is like the "memory of the future," that is, the certainty that God will intervene even in the darkest circumstances. The psalm is therefore very suitable for funeral celebrations, because it reinvigorates the faith and hope of the faithful even in times of sorrow, reminding them that God never abandons His people and always supports those who trust in Him.

*Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Corinthians (1:10-13, 17)

The port of Corinth, due to its strategic position between two seas and its lively trade, was a true crossroads of cultures, ideas and peoples. This explains why newly converted Christians reacted in different ways to the teachings of preachers: each traveller brought testimonies of the Christian faith according to his own experience, and the Corinthians were very sensitive, perhaps too sensitive, to beautiful words and persuasive arguments. In this context, divisions arose in the community: some referred to Paul, others to Apollos, others to Peter, and finally a group called themselves 'of Christ'. Paul not only condemns wrong behaviour, but sees in this phenomenon the risk of compromising the very meaning of baptism. Apollos, a Jew from Alexandria, is an emblematic example: an intellectual, well-versed in the Scriptures, eloquent and fervent, he was baptised only by John and perfected by Priscilla and Aquila in Ephesus. When he arrived in Corinth, he was very successful, but he never sought to become a personal leader and, in order not to fuel divisions, he then moved to Ephesus. This episode shows how passion and skills should not become a source of division, but should be put at the service of the community. Paul reminds the Corinthians of the truth of baptism: to be baptised means to belong to Christ, not to a human preacher. Baptism is a real and definitive union with Christ, who acts through the sacrament: as the Second Vatican Council says, 'when the priest baptises, it is Christ who baptises'. Paul also emphasises that preaching should not be based on eloquence or persuasive arguments, because the cross of Christ and love are not imposed by the force of words, but are lived and witnessed. The image of grafting clarifies this point well: what is important is the result – union with Christ – not who administered the baptism. What matters is fidelity to the message and love of Christ, not rhetorical skill or personal prestige. Ultimately, Paul's message to the Corinthians is universal and relevant: the unity of the Christian community is based on a common faith in Christ, not on leaders or human eloquence, and the true greatness of the Church lies in its spiritual cohesion, founded on baptism and belonging to Christ.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (4:12-23)

We are in chapter 4 of Matthew's Gospel. In the previous three chapters, Matthew has presented us with: first, a long genealogy that places Jesus in the history of his people, particularly in the lineage of David; then, the angel's announcement to Joseph: "Behold, the Virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and his name shall be called Emmanuel, which means God with us," a quotation from Isaiah, with the clarification that all this happened so that what the Lord had said through the prophet might be fulfilled, emphasising that the promises are finally fulfilled and the Messiah has arrived. The subsequent episodes reiterate this message of fulfilment: the visit of the Magi, the flight into Egypt, the massacre of the children of Bethlehem, the return from Egypt and the settlement in Nazareth, the preaching of John the Baptist, the baptism of Jesus and the Temptations. All these stories are full of biblical quotations and allusions. Now we are ready to listen to today's text, which is also rich in references: from the outset, Matthew quotes Isaiah to show the importance of Jesus' settlement in Capernaum. Capernaum is located in Galilee, on the shores of Lake Tiberias. Matthew specifies that it belongs to the territories of Zebulun and Naphtali: ancient names, no longer in common use, linked to Isaiah's promise that these once-humiliated lands would be illuminated by the glory of Galilee, 'the crossroads of the Gentiles' (Isaiah 8:23). The prophet continues: "The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light," a formula reminiscent of the sacred ritual of the coronation of a king, symbolising a new era. Matthew applies these words to the arrival of Jesus: the true King of the world has come; light has dawned on Israel and on humanity. Galilee, the crossroads of nations, becomes an open door to the world, from which the Messiah will spread salvation. Furthermore, Matthew already foreshadows future events: Jesus heads for Galilee after the arrest of John the Baptist, showing that Christ's life will be marked by persecution, but also by the final victory over evil: from every obstacle, God will bring forth good. Upon arriving in Capernaum, Matthew uses the expression "From then on," which is unique in the Gospel along with another in chapter 16, signalling a major turning point. Here it indicates the beginning of public preaching: "Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven is near." The other reference in chapter 16 will concern the passion and resurrection. This episode marks the transition from the time of promise to the time of fulfilment. The Kingdom is present, not only in words but in action: "Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the gospel of the Kingdom and healing every kind of disease and infirmity among the people." Isaiah's prophecy is fully realised: the Kingdom of God is among us. To spread this Good News, Jesus chooses witnesses, ordinary men, to join him in his mission of salvation. He calls them "fishers of men", that is, those who save from drowning, a symbol of their task of salvation. Thus the apostles become participants in the Saviour's mission.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Contrasting Presentation: Blessing of unlikely Stars

God hostage, or different view of danger

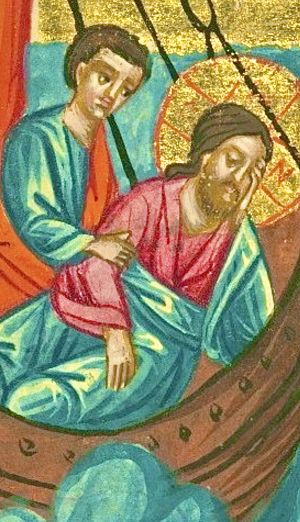

(Mk 4:35-41)

The whole Gospel of Mk is an articulated answer to the question: ‘who is Jesus?’ (v.41). His direction of travel seems to the wrong direction, and brazenly breaks the rules accepted by all.

While the disciples caressed nationalist desires, the Master begins to make it clear that He is not the vulgarly awaited Messiah, restorer of the late empire of David [or the Caesars, in succession struggle under the eyes of Mk’s Roman community: Galba, Oton, Vitellius, Vespasian].

The Kingdom of God is open to all humanity, which in those times of turmoil - torn apart by the civil war after Nero’s follies - sought security, hospitality, points of reference.

Everyone could find a home and shelter there (v.32b).

But some remained insensitive to an overly broad idea of Fraternity. The young Rabbi's proposal displaced them.

The teaching and call imposed on Jesus' intimates is to pass to the other shore (v.35), that is, not to hold back for oneself.

The Father's riches had to be communicated to the pagans.

Yet some “veterans” did not want to know about ‘risky disproportions’. They were calibrated on habits of common religiosity, and a circumscribed ideology of power.

So to exorcise the danger of the mission, they were already trying to take the Master hostage (v.36).

From the very beginning, the resistance to the divine office and the lacerating internal debate that had resulted from it, unleashed great storm in the assemblies of believers.

«And a large wind storm comes and the waves spilled into the boat, so that the boat was already filling up» (v.37).

The storm concerns the disciples, the only dismayed; not Jesus - at the stern, that is, at the helm, driving the boat [v. 38 - and on the «cushion»: it is about the Risen One].

What happens ‘inside’ is not a simple reflection of what happens "outside"! This is the mistake to be corrected.

From the peace of the divine condition that dominates chaos (v.39) the Lord draws attention and reproaches the apostles, accusing them of not having «Faith» (v.40).

In short, are we confused, embarrassed, and is the chaos of the schemes raging? Paradoxically, we are on the right path of the Exodus - but we must not get caught up in fear.

Emotionally relevant situations make sense, carry a meaningful appeal, introduce a different introspection, the decisive change; a new 'Genesis'.

Trial in fact activates souls in the most effective way, because it disengages us from the idea of stability, and brings us into contact with dormant energies, initiating the ‘new dialogue with events’.

In Him, we are therefore imbued with a different vision of danger.

Indeed, it seems that Jesus expressly wants the “dark moments” of confrontation and doubt (v.35).

Textbook expectations and the habit of setting up conformist harmonies block the flowering of what we are and hope for.

What is annoying or even ‘against’ has something decisive to tell us.

So even in the little boat of the churches (v.36) the discomfort must express itself.

Ours is an inverted, upside down, unequaled stability - uncertain, inconvenient - yet energetic, capable of reinventing itself.

It will even be excessive, but from the disruptions. And observing in others our own dark sides.

For a proposal of Tenderness without a plan, not corresponding; wich is not a relaxation area.

Love that rhymes with terrible anxiety, which however puts us in immediate contact with our deepest layers - and the ‘suburbs’!

[Saturday 3rd wk. in O.T. January 31, 2025]

God as hostage, or the different view of danger

(Mk 4:35-41)

Excita, Domine, potentiam tuam, et veni

"Excita, Domine, potentiam tuam, et veni" - with these and similar words the Church's liturgy repeatedly prays [...].

These invocations were probably formulated in the period of the decline of the Roman Empire. The disintegration of the supporting orders of law and of the basic moral attitudes, which gave them strength, caused the breaking of the banks that had hitherto protected peaceful coexistence between men. A world was passing away. Frequent natural cataclysms further increased this experience of insecurity. No force could be seen to halt this decline. All the more insistent was the invocation of God's own power: that He would come and protect men from all these threats.

"Excita, Domine, potentiam tuam, et veni". Today, too, we have many reasons to associate ourselves with this prayer [...] The world with all its new hopes and possibilities is, at the same time, distressed by the impression that the moral consensus is dissolving, a consensus without which legal and political structures do not function; consequently, the forces mobilised to defend these structures seem doomed to failure.

Excita - the prayer is reminiscent of the cry addressed to the Lord, who was sleeping in the disciples' storm-tossed boat that was close to sinking. When His powerful word had calmed the storm, He rebuked the disciples for their little faith (cf. Mt 8:26 and par.). He wanted to say: in yourselves faith has slept. He also wants to say the same thing to us. Even in us so often faith sleeps. Let us therefore pray to Him to awaken us from the sleep of a faith that has become tired and to restore to faith the power to move mountains - that is, to give right order to the things of the world.

[Pope Benedict, to the Roman Curia 20 December 2010].

The whole Gospel of Mark is an articulate answer to the question: 'who is Jesus?' (v.41).

The direction of travel imposed by Jesus on his followers seems to go against the grain, and brazenly breaks the rules accepted by all.

While the disciples were fondling nationalist desires, the Master begins to make it clear that He is not the vulgarly expected Messiah, restorer of the defunct empire of David.

[Or of the Caesars, then struggling for succession under the eyes of the Roman community of Mk: Galba, Otone, Vitellius, Vespasian].

The Kingdom of God is open to all mankind, who in those turbulent times - torn apart by the swift but bloody civil war that followed Nero's follies - sought security, welcome, points of reference.

Everyone could find home and shelter there (Mk 4:32b).

But the still Judaizing apostles and church veterans seemed averse to Christ's proposals; they remained insensitive to an overly broad idea of fraternity.

Compared to the teaching received from the fathers of the ancient tradition, the young Rabbi's proposal displaced them.

It is a problem that is still alive and very serious.

The teaching and reminder imposed on Jesus' intimates was to pass to the other shore (Mk 4:35; Lk 8:22), that is, not to keep for oneself.

The riches of the Father were to be communicated to the pagans, commonly considered unclean and infamous.

Yet his people did not want to know about risky disproportions, which would make the unpredictable action of the Son of God stand out.

They were calibrated to common religiosity customs and a circumscribed ideology of power.

So to exorcise the danger of the mission - and having to accommodate people, rework situations, welcome surprises that would agitate them [questioning them] - they attempted to take the Master hostage (v.36).

From the very beginning, the resistance to the divine commission and the resulting lacerating internal debate stirred up a great storm in the assemblies of believers.

"And behold, there came a great stirring in the sea, so that the boat was covered with waves" (Mt 8:24).

"And there came a great gale of wind, and the waves rolled into the boat, so that the boat was already filled" (Mk 4:37).

The storm affected only the disciples, the only ones dismayed; not Jesus: "but he was asleep" (Mt 8:24).

"In the stern" (Mk 4:38), that is, at the helm, leading.

And "on the pillow" (Mk 4:38): this is the Risen One - well alive although apparently absent.

What happens "inside" is not a mere reflection of what happens "outside"! This is the error to be corrected.

Such identification blocks and makes life chronic, starting with the handling of emotionally relevant situations - which have their own meaning.

They carry a meaningful appeal, they introduce a different eye and dialogue.

Even from the peace of the divine condition that dominates chaos, the Lord calls attention to and rebukes the apostles, accusing them of not having "Faith" (v.40).

Here by Faith is meant an ounce of risk of love - like a "mustard seed" (v.31) - to be brought to humanity for renewal.

In short, we are confused, embarrassed, and the chaos of schemes rages on, not excluding healthy selfishness for our destiny?

We are paradoxically on the right path of the Exodus - but we must not get caught up in fear.

In Him, we are imbued with a different view of danger.

Says the Tao Tê Ching (xxii): "The saint does not see by himself, therefore he is enlightened. Even in straits.

Indeed, it seems that Jesus expressly wanted the dark moments of confrontation and doubt for the apostles (Mk 4:35; Lk 8:22b).

This is also true for us, even if we were church leaders; otherwise there will be no cleansing from repetitive convictions.

Textbook expectations and the habit of setting up conformist harmonies block the flowering of what we are and hope for.

Especially what is annoying or even 'against' has something decisive to tell us.

Even in the little boat of the churches (Mk 4:36), discomfort must express itself:

"And He was in the stern, on the pillow, asleep. And they woke him up and said to him, "Master do you not care that we are lost?" (v.38).

"And drawing near they woke him, saying, Lord, save us, we are lost" (Mt 8:25).

All this is to revive the essence of each person and of the community itself.

To introduce the hidden or repressed change, and to activate it in the most effective way.

In every situation, it is good to be activated by contact with the hidden or primordial energies.

More than opposing frictions and conflicting external events, anxiety, impression and anguish come from the very fear of facing the normal or decisive questions of existence.

This is out of mistrust: feeling in danger perhaps only because we perceive ourselves to be intimately undeveloped, incapable of other conversation, of having the guts to discover and rework, convert, or remodel.

The fatigue of questioning ourselves and the suffering that the adventure of Faith holds, will also fade amidst the discomfort of the rough sea - which precisely does not want us to return to 'those of before'.

It is enough to disengage ourselves from the idea of stability, even religious stability, and listen to life as it is, embracing it.

Recognising it as one's own even in its crowd of bumps, bitterness, dashed hopes of harmony, sorrows...

Engaging with this flood of new emergencies, and encountering one's own profound nature.

The best vaccine against the anxieties of the adventure together with Christ on the changing waves of the unexpected, will be precisely not to avoid worries upstream - on the contrary, to go towards them and welcome them; to recognise them, to let them happen.

Even in times of global crisis, the apprehensions that seem to want to devastate us, come to us as preparatory energies of other joys that wish to break through.

The upheavals are arranging new cosmic attunements; for wonderment starting with ourselves. As a present guide, and an appeal from beyond.

Our little boat is in an inverted stability, upside down, unequal - uncertain, inconvenient - yet energetic, prickly, capable of reinventing itself.

It may even be excessive, but it is disruptive. And by observing in others their own dark sides.

For a proposal of Tenderness without a plan, not corresponding; which is not a relaxation zone.

Love that rhymes with terrible anxiety, which, however, puts us in immediate contact with our deepest layers - and peripheries!

To internalise and live the message:

On what occasions have you found easy what previously seemed impossible?

Do you ever get in the way?

Is your life the same or different - able to address and accommodate the distant or new?

Some other providence, which you ignore

"It is good not to fall, or to fall and rise again. And if you do happen to fall, it is good not to despair and not to become estranged from the love the Sovereign has for man. For if he wills, he can do mercy to our weakness. Only let us not turn away from him, let us not be distressed if we are forced by the commandments, and let us not be disheartened if we come to nothing [...].

Let us neither hurry nor retreat, but always begin again [...].

Wait for him, and he will show you mercy, either by conversion or by trials, or by some other providence that you do not know."

[Peter Damascene, Second Book, Eighth Discourse, in La Filocalia, Turin 1982, I,94].

A mixture of fear and trust, or total and pure abandonment

We have just heard the Gospel reading of the calming of the storm, which was presented with a brief but incisive passage from the Book of Job, in which God reveals himself as the Lord of the sea. Jesus rebukes the wind and orders the sea to be calm, he speaks to it as if it were identified with the power of the devil. In fact, according to what the First Reading and Psalm 107[106] tell us, in the Bible the sea is considered a threatening, chaotic and potentially destructive element which God the Creator alone can dominate, govern and calm.

Yet, there is another force a positive force that moves the world, capable of transforming and renewing creatures: the power of "Christ's love" (2 Cor 5: 14) as St Paul calls it in his Second Letter to the Corinthians not, therefore essentially a cosmic force, but rather divine, transcendent. It also acts on the cosmos but, in itself, Christ's love is "another" power and the Lord manifested this transcendent otherness in his Pasch, in the "holiness" of the "way" he chose to free us from the dominion of evil, as happened for the Exodus when he brought the Jews out of Egypt through the waters of the Red Sea. "Your way, O God, is holy", the Psalmist exclaims, "Your way was through the sea/ your path through the great waters" (Ps 77[76]: 13, 19). In the Paschal Mystery, Jesus passed through the abyss of death, because in this way God wanted to renew the universe through the death and Resurrection of his Son, who "died for all", that all might live "for him who for their sake died and was raised" (2 Cor 5: 15), and not live for their own sake alone.

The solemn gesture of calming the stormy sea was a clear sign of Christ's lordship over negative powers and induces one to think of his divinity: "Who then is this", his own Disciples asked fearfully, "that even wind and sea obey him?" (Mk 4: 41). Their faith is not yet firm, it is being formed; it is a mingling of fear and trust; on the other hand, Jesus' confidant abandonment to the Father is total and pure. This is why he could sleep during the storm, completely safe in God's arms. The time would come, however, when Jesus too would feel fear and anguish, when his hour came he was to feel the full burden of humanity's sins upon him, like a wave at high tide about to break over him. That was indeed to be a terrible tempest, not cosmic but spiritual. It was to be the final, extreme assault of evil against the Son of God.

Yet, in that hour Jesus did not doubt in the power of God the Father or in his closeness, even though he had to experience to the full the distance of hatred from love, of falsehood from the truth, of sin from grace. He experienced this drama in himself with excruciating pain, especially in Gethsemane, before his arrest, and then throughout his Passion until his death on the Cross. In that hour, Jesus on the one hand was one with the Father, fully abandoned to him; on the other, since he showed solidarity to sinners, he was as it were separated and felt abandoned by Him.

[Pope Benedict, homily 21 June 2009]

Sign of a constant Presence

The storm calmed on the Lake of Genesaret can be reread as a "sign" of Christ's constant presence in the "boat" of the Church, which many times throughout history is exposed to the fury of the winds during stormy hours. Jesus, awakened by the disciples, commands the winds and the sea to be becalmed. Then he says to them, "Why are you so fearful? Have you no faith yet?" (Mk 4:40). In this, as in other episodes, one can see Jesus' desire to inculcate in the apostles and disciples faith in his operative and protective presence even in the most stormy hours of history, in which doubt about his divine assistance could infiltrate the spirit. In fact, in Christian homiletics and spirituality, the miracle has often been interpreted as a 'sign' of Jesus' presence and a guarantee of trust in him on the part of Christians and the Church.

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 2 December 1987]

Against the tidal waves, one must look to the Lord and raise one's voice

Today’s liturgy tells the episode of the storm calmed by Jesus (Mk 4:35-41). The boat in which the disciples are crossing the lake is beaten by the wind and the waves and they fear they will sink. Jesus is with them on the boat, yet he is in the stern asleep on the cushion. Filled with fear, the disciples cry out to him: “Teacher, do you not care if we perish?” (v. 38).

And quite often we too, beaten by the trials of life, have cried out to the Lord: “Why do you remain silent and do nothing for me?”. Especially when it seems we are sinking, because love or the project in which we had laid great hopes disappears; or when we are at the mercy of unrelenting waves of anxiety; or when we feel we are drowning in problems or lost amid the sea of life, with no course and no harbour. Or even, in moments in which the strength to go forward fails us, because we have no job, or an unexpected diagnosis makes us fear for our health or that of a loved one. There are many moments when we feel we are in a storm; when we feel we are almost done in.

In these situations and in many others, we too feel suffocated by fear and, like the disciples, risk losing sight of the most important thing. In the boat, in fact, even if he is sleeping, Jesus is there, and he shares with his own all that is happening. If on the one hand his slumber surprises us, on the other, it puts us to the test. The Lord is there, present; indeed, he waits — so to speak — for us to engage him, to invoke him, to put him at the centre of what we are experiencing. His slumber causes us to wake up. Because to be disciples of Jesus, it is not enough to believe God is there, that he exists, but we must put ourselves out there with him; we must also raise our voice with him. Hear this: we must cry out to him. Prayer is often a cry: “Lord, save me!”. I was watching, on the programme “In his Image”, today, the Day of Refugees, many who come in large boats and at the moment of drowning cry out: “Save us!”. In our life too the same thing happens: “Lord, save us!”, and prayer becomes a cry.

Today we can ask ourselves: what are the winds that beat against my life? What are the waves that hinder my navigation, and put my spiritual life, my family life, even my psychological life in danger? Let us say all this to Jesus; let us tell him everything. He wants this; he wants us to grab hold of him to find shelter from the unexpected waves in life. The Gospel recounts that the disciples approach Jesus, wake him and speak to him (cf. v. 38). This is the beginning of our faith: to recognize that alone we are unable to stay afloat; that we need Jesus like sailors need the stars to find their course. Faith begins from believing that we are not enough for ourselves, from feeling in need of God. When we overcome the temptation to close ourselves off, when we overcome the false religiosity that does not want to disturb God, when we cry out to him, he can work wonders in us. It is the gentle and extraordinary power of prayer, which works miracles.

Jesus, begged by the disciples, calms the wind and waves. And he asks them a question, a question which also pertains to us: “Why are you afraid? Have you no faith?” (v. 40). The disciples were gripped with fear, because they were focused on the waves more than on looking at Jesus. And fear leads us to look at the difficulties, the awful problems, and not to look at the Lord, who many times is sleeping. It is this way for us too: how often we remain fixated on problems rather than going to the Lord and casting our concerns to him! How often we leave the Lord in a corner, at the bottom of the boat of life, to wake him only in a moment of need! Today, let us ask for the grace of a faith that never tires of seeking the Lord, of knocking at the door of his Heart. May the Virgin Mary, who in her life never stopped trusting in God, reawaken in us the basic need of entrusting ourselves to him each day.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 20 June 2021]

Blessed are the poor in spirit, because of the Holy Spirit

And quite often we too, beaten by the trials of life, have cried out to the Lord: “Why do you remain silent and do nothing for me?”. Especially when it seems we are sinking, because love or the project in which we had laid great hopes disappears (Pope Francis)

E tante volte anche noi, assaliti dalle prove della vita, abbiamo gridato al Signore: “Perché resti in silenzio e non fai nulla per me?”. Soprattutto quando ci sembra di affondare, perché l’amore o il progetto nel quale avevamo riposto grandi speranze svanisce (Papa Francesco)

The Kingdom of God grows here on earth, in the history of humanity, by virtue of an initial sowing, that is, of a foundation, which comes from God, and of a mysterious work of God himself, which continues to cultivate the Church down the centuries. The scythe of sacrifice is also present in God's action with regard to the Kingdom: the development of the Kingdom cannot be achieved without suffering (John Paul II)

Il Regno di Dio cresce qui sulla terra, nella storia dell’umanità, in virtù di una semina iniziale, cioè di una fondazione, che viene da Dio, e di un misterioso operare di Dio stesso, che continua a coltivare la Chiesa lungo i secoli. Nell’azione di Dio in ordine al Regno è presente anche la falce del sacrificio: lo sviluppo del Regno non si realizza senza sofferenza (Giovanni Paolo II)

For those who first heard Jesus, as for us, the symbol of light evokes the desire for truth and the thirst for the fullness of knowledge which are imprinted deep within every human being. When the light fades or vanishes altogether, we no longer see things as they really are. In the heart of the night we can feel frightened and insecure, and we impatiently await the coming of the light of dawn. Dear young people, it is up to you to be the watchmen of the morning (cf. Is 21:11-12) who announce the coming of the sun who is the Risen Christ! (John Paul II)

Per quanti da principio ascoltarono Gesù, come anche per noi, il simbolo della luce evoca il desiderio di verità e la sete di giungere alla pienezza della conoscenza, impressi nell'intimo di ogni essere umano. Quando la luce va scemando o scompare del tutto, non si riesce più a distinguere la realtà circostante. Nel cuore della notte ci si può sentire intimoriti ed insicuri, e si attende allora con impazienza l'arrivo della luce dell'aurora. Cari giovani, tocca a voi essere le sentinelle del mattino (cfr Is 21, 11-12) che annunciano l'avvento del sole che è Cristo risorto! (Giovanni Paolo II)

Christ compares himself to the sower and explains that the seed is the word (cf. Mk 4: 14); those who hear it, accept it and bear fruit (cf. Mk 4: 20) take part in the Kingdom of God, that is, they live under his lordship. They remain in the world, but are no longer of the world. They bear within them a seed of eternity a principle of transformation [Pope Benedict]

Cristo si paragona al seminatore e spiega che il seme è la Parola (cfr Mc 4,14): coloro che l’ascoltano, l’accolgono e portano frutto (cfr Mc 4,20) fanno parte del Regno di Dio, cioè vivono sotto la sua signoria; rimangono nel mondo, ma non sono più del mondo; portano in sé un germe di eternità, un principio di trasformazione [Papa Benedetto]

In one of his most celebrated sermons, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux “recreates”, as it were, the scene where God and humanity wait for Mary to say “yes”. Turning to her he begs: “[…] Arise, run, open up! Arise with faith, run with your devotion, open up with your consent!” [Pope Benedict]

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.