don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Jesus' initiative and state of life

1. What is most important in the old and new forms of 'consecrated life' is that in them one discerns the fundamental conformity to the will of Christ, the institutor of the evangelical counsels and, in this sense, the founder of religious life and of every similar state of consecration. As the Second Vatican Council says, the evangelical counsels are "founded on the words and examples of the Lord" (Lumen Gentium, 43).

There has been no shortage of those who have questioned this foundation by considering consecrated life as a purely human institution, born of the initiative of Christians who wished to live the Gospel ideal more deeply. Now it is true that Jesus did not directly found any of the religious communities that gradually developed in the Church, nor did He determine particular forms of consecrated life. But what He willed and instituted is the state of consecrated life, in its general value and in its essential elements. There is no historical evidence to explain this state by a later human initiative, nor is it easily conceivable that consecrated life - which has played such a great role in the development of holiness and the mission of the Church - did not proceed from a founding will of Christ. If we explore the Gospel accounts well, we discover that this will appears in a very clear way.

2. It appears from the Gospel that from the very beginning of his public life Jesus calls men to follow him. This call is not necessarily expressed in words: it can simply result from the attraction exercised by Jesus' personality on those he meets, as in the case of the first two disciples, according to the account in John's Gospel. Already disciples of John the Baptist, Andrew and his companion (who seems to be the evangelist himself) are fascinated and almost gripped by the one who is presented to them as 'the lamb of God'; and they immediately set out to follow Jesus, before he has even spoken a word to them. When Jesus asks, "What do you seek?", they respond with another question: "Master, where do you dwell?". Then they receive the invitation that will change their lives: "Come and see" (cf. Jn 1:38-39).

But generally the most characteristic expression of the call is the word: "Follow me" (Mt 8:22; 9:9; 19:21; Mk 2:14; 10:21; Lk 9:59; 18:22; Jn 1:43; 21:19). It manifests the initiative of Jesus. Before then, those who wished to embrace the teaching of a master chose the one whose discipleship they wished to become. Jesus, on the other hand, with that word: 'Follow me', shows that it is he who chooses those whom he wants to have as companions and disciples. Indeed, he will say to the Apostles: "You did not choose me, but I chose you" (Jn 15:16).

In this initiative of Jesus appears a sovereign will, but also an intense love. The account of the call addressed to the rich young man reveals this love. We read there that when the young man declares that he has kept the commandments of the law from an early age, Jesus, "gazing at him, loved him" (Mk 10:21). This penetrating gaze, filled with love, accompanies the invitation: "Go, sell what you have and give to the poor and you will have treasure in Heaven, then come and follow me" (Ibid). This divine and human love of Jesus, so ardent as to be recalled by a witness to the scene, is what is repeated in every call to total self-giving in the consecrated life. As I wrote in the Apostolic Exhortation Redemptionis donum, "in it is reflected the eternal love of the Father, who 'so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life' (Jn 3:16)" (John Paul II, Redemptionis donum, no. 3).

3. Again according to the testimony of the Gospel, the call to follow Jesus involves very wide-ranging demands: the account of the invitation to the rich young man emphasises the renunciation of material goods; in other cases the renunciation of the family is more explicitly emphasised (cf. Lk 9:59-60). Generally speaking; following Jesus means renouncing everything to join him and accompany him on the paths of his mission. And the renunciation to which the Apostles consented, as Peter declares: "Behold, we have left everything and followed you" (Mt 19, 27). Precisely in his reply to Peter Jesus indicates the renunciation of human goods as a fundamental element of his following (cf. Mt 19:29). It is clear from the Old Testament that God asked his people to follow him through the observance of the commandments, but without ever making such radical demands. Jesus manifests his divine sovereignty by demanding instead an absolute dedication to him, even to the point of total detachment from earthly goods and affections.

4. Note, however, that while formulating the new demands included in the call to follow him, Jesus presents them to the free choice of those he calls. They are not precepts, but invitations or "advice". The love with which Jesus addresses the call to him, does not deprive the rich young man of the power of free decision, as shown by his refusal to follow him because of the preference given to the goods he possesses. The evangelist Mark notes that he "went away sorrowful, for he had many possessions" (Mk 10:22). Jesus does not condemn him for this. But in his turn he observes not without a certain affliction that it is difficult for the rich to enter the kingdom of heaven, and that only God can work certain detachments, certain inner liberations, that allow one to respond to the call (cf. Mk 10:23-27).

5. On the other hand, Jesus assures that the renunciations required by the call to follow him obtain their reward, a "heavenly treasure", that is, an abundance of spiritual goods. He even promises eternal life in the century to come, and a hundredfold in this century (cf. Matthew 19:29). This hundredfold refers to a higher quality of life, to a higher happiness.

Experience teaches that the consecrated life, according to Jesus' design, is a profoundly happy life. This happiness is commensurate with fidelity to Jesus' plan. It does not preclude the fact that, again according to Mark's mention of persecution in the same episode (Mk 10:30), the "hundredfold" does not dispense from association with the cross of Christ.

6. Jesus also called women to follow him. An account in the Gospels says that a group of women accompanied Jesus, and that these women were numerous (cf. Lk 8:1-3; Mt 27:55; Mk 15:40-41). This was a great novelty in relation to Judaic customs: only the innovative will of Jesus, which included the promotion and to some extent the liberation of women, can explain the fact. No account of any woman's vocation has reached us from the Gospels; but the presence of numerous women with the Twelve with Jesus presupposes his call, his choice, whether silent or expressed.

In fact, Jesus shows that the state of consecrated life, consisting in following him, is not necessarily linked to a destination to the priestly ministry, and that this state concerns both women and men, each in his own field and with the function assigned by the divine call. In the group of women who followed Jesus, one can discern the announcement and indeed the initial nucleus of the immense number of women who will commit themselves to religious life or other forms of consecrated life, throughout the centuries of the Church, up to the present day. This applies to the "consecrated women", but also to so many of our sisters who follow in new forms the authentic example of the co-workers of Jesus: e.g. as lay "volunteers" in so many works of the apostolate, in so many ministries and offices of the Church.

7. Let us conclude this catechesis by recognising that Jesus, in calling men and women to abandon everything to follow him, inaugurated a state of life that would gradually develop in his Church, in the various forms of consecrated life, concretised in religious life, or even - for those chosen by God - in the priesthood. From Gospel times to the present day, the founding will of Christ has continued to operate, expressed in that beautiful and most holy invitation addressed to so many souls: "Follow me!"

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 12 October 1994]

Fulfilment of the Promises: He is the Good News. And the Time of Salvation

The Gospel today presents to us the beginning of Jesus’ preaching ministry in Galilee. St Mark stresses that Jesus began to preach “after John [the Baptist] was arrested” (1:14). Precisely at the moment in which the prophetic voice of the Baptist, who proclaimed the coming of the Kingdom of God, was silenced by Herod, Jesus begins to travel the roads of his land to bring to all, especially the poor, “the gospel of God” (cf. ibid.). The proclamation of Jesus is like that of John, with the essential difference that Jesus no longer points to another who must come: Jesus is Himself the fulfilment of those promises; He Himself is the “good news” to believe in, to receive and to communicate to all men and women of every time that they too may entrust their life to Him. Jesus Christ in his person is the Word living and working in history: whoever hears and follows Him may enter the Kingdom of God.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 25 January 2015].

The Gospel passage [...] (cf. Mk 1:14-20) shows us, so to speak, the “passing of the baton” from John the Baptist to Jesus. John was His precursor; he prepared the terrain for Him and he prepared the way for Him: Jesus can now begin his mission and announce the salvation by now present; He was the salvation. His preaching is summarized in these words: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent, and believe in the gospel” (v. 15). Simply. Jesus did not mince words. It is a message that invites us to reflect on two essential themes: time and conversion.

In this text of Mark the Evangelist, time is to be understood as the duration of the history of salvation worked by God; therefore, the time “fulfilled” is that in which this salvific action reaches its pinnacle, full realization: it is the historical moment in which God sent his Son into the world and his Kingdom was rendered more “close” than ever. The time of salvation was fulfilled because Jesus arrived. However, salvation is not automatic; salvation is a gift of love and as such, it is offered to human freedom. Always, when we speak of love, we speak of freedom: love without freedom is not love; it may be interest, it may be fear, many things, but love is always free, and being free it calls for a freely given response: it calls for our conversion. Thus, it means changing mentality — this is conversion, changing mentality — and changing life: no longer following the examples of the world but those of God, who is Jesus; following Jesus; “doing” as Jesus had done, and as Jesus taught us. It is a decisive change of view and attitude. In fact, sin — above all the sin of worldliness which is like air, it permeates everything — brought about a mentality that tends toward the affirmation of oneself against others and against God. This is curious... What is your identity? And so often we hear that one’s identity is expressed in terms of “opposition”. It is difficult to express one’s identity in the worldly spirit, in positive terms and in those of salvation: it is against oneself, against others and against God. And for this purpose it does not hesitate — the mentality of sin, the worldly mentality — to use deceit and violence. Deceit and violence. We see what happens with deceit and violence: greed, desire for power and not service, war, exploitation of people... This is the mentality of deceit that definitely has its origins in the father of deceit, the great pretender, the devil. He is the father of lies, as Jesus defines him.

All this is opposed by the message of Jesus, who invites us to recognize ourselves as in need of God and his grace; to have a balanced attitude with regard to earthly goods; to be welcoming and humble toward everyone; to know and fulfil ourselves in the encounter with and service of others. For each one of us the time in which we are able to receive redemption is brief: it is the duration of our life in this world. It is brief. Perhaps it seems long... I remember that I went to administer the Sacraments, the Anointing of the Sick, to a very good elderly man, very good, and in that moment, before receiving the Eucharist and the Anointing of the Sick, he said this phrase to me: “My life flew by”. This is how we, the elderly, feel, that life has passed away. It passes away. And life is a gift of God’s infinite love, but it is also the time to prove our love for him. For this reason every moment, every instant of our existence is precious time to love God and to love our neighbour, and thereby enter into eternal life.

The history of our life has two rhythms: one, measurable, made of hours, days, years; the other, composed of the seasons of our development: birth, childhood, adolescence, maturity, old age, death. Every period, every phase has its own value, and can be a privileged moment of encounter with the Lord. Faith helps us to discover the spiritual significance of these periods: each one of them contains a particular call of the Lord, to which we can give a positive or negative response. In the Gospel we see how Simon, Andrew, James and John responded: they were mature men; they had their work as fishermen, they had their family life... Yet, when Jesus passed and called to them, “immediately they left their nets and followed him” (Mk 1:18).

Dear brothers and sisters, let us be attentive and not let Jesus pass by without welcoming him. Saint Augustine said “I am afraid of God when he passes by”. Afraid of what? Of not recognizing him, of not seeing him, not welcoming him.

May the Virgin Mary help us live each day, each moment as the time of salvation, when the Lord passes and calls us to follow him, each according to his or her life. And may she help us to convert from the mentality of the world, that of worldly reveries that are fireworks, to that of love and service.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 24 January 2021]

Loving one’s limits: between Faith and religion

The muddy condition of the Jordan and the human dimension of Jesus

(Mt 3:13-17; Mk 1:7-11; Lk 3:21-22; Jn 1:30-34)

The Jordan River was never navigable; it simply marked a border. In the mentality of time, between the land of others and the sacred realm of freedom; and here is the concrete distinction of the Incarnation.

Let us outline some considerations that recover the meaning of this historical fact - which for us can be like a ‘sun’ inside - with which the liturgy completes the path of Christmas time.

Jesus was in search, eager to sift, to learn.

It may seem incredible to us, but he recognized himself ignorant, in need of evolving - not of becoming “better” and stronger, but of ‘looking inside’ things - and move the gaze elsewhere.

In that strongly engaged but overly serious environment he understood definitively who the Subject of the spiritual journey is: the divine Life, which draws us into the experience of happiness, of authentic and solid love.

The Kingdom cannot be prepared and even set up [it would become a projection, a conditioned reflection, an outer tower, like Babel] - rather, it must be Welcomed. Because it Comes.

The results that appeal to our genius and muscles, at first they are unnerving, then they become frustrating; lastly they block the growth of the innate universe, because they turn off the novelties, obfuscate the Source of being and enthusiasm.

The religious man who does not make the leap of the Faith, stagnates in the depressing finding of the difference between expected results and concrete facts.

Paradoxically, he focuses the streets on himself, but doesn’t lays his eye ‘on’ his essence. He obeys - perhaps - but doesn’t listen.

Having lost the even relational sense of his unrepeatable Unicum - he measures all his inability to perceive, elaborate, realize, those designs that guide his dreams and resources to fullness.

He loses all his energy by making induced, contrived, off-scale resolutions, wich make him supposing and acidic - simply because those artifact targets dry him down: they do not concern him.

Meanwhile, the "perfect" and stressful discipline that imposes to himself, as if he were the Protagonist, takes away from him the joy of meeting his superior talents and fully experiencing what reality provides.

Perhaps he does not extract from his own ‘mine’ (entirely at hand) those abilities that realize the personal Mission.

He does not even notice it - all caught by absolutely derived or conforming ideas and disciplines, able only to dismantle his peaks and rarity.

Always with a look on the past, or on the common [even glamorous] thinking of the authorities, of others, of the surrounding environment - and what is believed "should be", according to established and damping ethicalisms.

Finally, the discrepancy between what to wich one has given so much [without perhaps ever understanding what God is really calling to] and what has been achieved, destroys the exceptionality.

It weakens Hope itself, triggering an inexorable sadness, or the useless individual and ecclesial routine.

Adult Jesus who lets himself be immersed in the waters of the Jordan is icon of a proposal that sublimates the conspicuously murky swamps of our condition.

Not only by seeing the possibilities, but even making them ‘cheerful’: so in all the oriental icons, which accentuate their elegant volutes.

How can our Lord stand beside an indistinct crowd of sinners and skids, seeking redemption?

Jesus noticed: in each one of them surfaced a talent. And we are at the lowest point on earth - 400 meters below sea level.

This is precisely the leap in quality that discriminates against a simple-minded religiosity [even cloaked in great things] and the growth of Faith.

The Son reveals divine life, which is manifested ceaselessly ‘friend’. Face of God that does not destroy but approaches, to bring out the stifled possibilities.

He doesn’t crush, humiliating our inclinations, and adding unbearable burdens. He’s not the King of submissive and fatigued persons.

He enters a reality also made of mud, but that prepares our developments, and desires to grow - producing paths often interrupted, but finally the unexpected Flower.

In this way we learn to love our limits and the many slimy conditions: they remind us of the Jordan.

Earth needs Light, but Light needs ‘earth’. They are expression of the New Covenant.

[Baptism of the Lord; homily. For a perhaps more fussy and characteristic biblical relief, cf. the extended comment, at the bottom of the site: www.duevie.art]

Wanting to live within one's limits: the possibility of reinventing oneself, in Happy waters

The muddy condition of the Jordan and the human dimension of Jesus

(Mt 3:13-17; Mk 1:7-11; Lk 3:21-22; Jn 1:30-34)

The river Jordan was never navigable; it simply marked a border.

In the mentality of the time, between other people's land and the sacred sphere of freedom: here a concrete boundary of the "Incarnation".

Let us try to explore this in more detail.

Popular preaching on the subject of the Baptism of the Lord was burdened with a bark of clichés [here and there perhaps insuperable] that prevented any maturation of widespread beliefs, which were still stagnant.

In this way, Jesus has hastily found himself placed behind the clouds, and today it is difficult to explain what he has in common with our life, which is often raw, conditioned by fatigue, trial and error, and research.

Although fundamental for the fruitful interiorization of a journey that moves away from generically (sometimes authentically) devotional banalities, from the ambo and in catechesis we are still forced to dribble the true meaning of the event.

Indeed, the Baptism of the Lord has created embarrassment and interpretative confusion since the first generations of believers.

Let us deal with a few considerations that recover the meaning of this historical fact - for us, it could be like a sunshine inside - with which the liturgy completes the journey of the Christmas season.

Jesus, in search of and eager to sift through the best teaching of his time, enters the school of the Baptist as a pupil.

For this reason he is baptised by John - and through this rite of entry, joined with other ordinary followers.

It may seem incredible, but the Master and Lord recognised himself as curious, imperfect, ignorant, incomplete; in need of evolution. Not to become 'better' and stronger, but to learn to look otherwise.

In that highly committed but serious, edgy, often one-sided environment, He understood the true greatness of Revelation.

In short, the Subject of the spiritual journey is divine Life, with all its bearing, which providentially pours forth and moves varied situations.

It comes to broaden horizons; not to bind us to particular ways of understanding and wanting.

We already know: it is not the ego that thinks and plans that can draw us into the experience of integral, all-embracing Happiness; of authentic, solid love.

The Kingdom is anything but: Complete. It is inclusive of what the sterilised, or fashionable, and common opinion does not 'like'.

It offers an earthly energy that is as valuable as the ideal, heavenly one.

Heaven cannot be prepared or even set up: it would become a projection, a conditioned reflex, an external tower like Babel.

Rather, one must welcome it, host it within oneself.

Then another kind of asceticism opens up, with fewer expectations of "perfection". A path that disconcerts, and that the divine impulse within us - concrete - demands of us.

We will know the Joy of Living, we will feel it flowing within; only then will we be fulfilled.

Marrying the shadow side, which will become our Perfume.

Achievements that rely on genius and muscle, first unnerving, then frustrating; then blocking the growth of the innate universe.

Artifices external to the soul extinguish personally inspired novelty, the very Source of being and enthusiasm.

Indeed, the one-sided religious man remains in malaise; he withers, because he does not take the spousal, creative leap of the adventure of Faith.

He becomes a photograph or a photocopy.

Then it stagnates in the depressing realisation of the difference between expected results and concrete facts.

Paradoxically, it centres the ways on itself - but does not rest its gaze 'in' its essence.

It obeys perhaps, but does not listen. Thus it allows itself to be vampirised by mannerisms and epidermal stylistic features.

Having lost the sense, also relational, of its unrepeatable Unicum - it measures all its inability to perceive, elaborate, realise mysterious designs that guide dreams and resources to fullness.

He loses all energy by making induced resolutions, full of artifice; out of scale.

He gives himself goals that make him opinionated, sour, formal, external - simply because those overarching goals do not concern him.

Meanwhile, the perfect, stressful discipline he imposes on himself, as if he were the Protagonist, takes away the joy of encountering superior talents.

He will always miss the thrill of living intensely what (fuller) reality offers.

Thus he does not extract from his own Mine all at hand those abilities that realise the personal Mission.

He does not even realise it - caught up in hyperbolic ideas and great disciplines that are absolutely derivative, paradoxically trivial [which can finally only dismantle its peaks and rarity].

He always has his eye on the past or on fashions; on the common thought, that of the situation, of the authorities, of others, of the environment he frequents, of the surroundings - which he tarnishes, or deviates.

And it places the focus only on what is normally considered 'should be' - according to established, dampening ethics, or utopias à la page, disembodied.

Inside the vortex of insuperable models, he never understands what God is really calling him to, even in disturbances.

Finally, every discrepancy between what is given and what is obtained destroys the atypicality of Hope itself, triggering an inexorable sadness, or the useless individual and ecclesial trance.

The adult Jesus who allows himself to be immersed in the waters of the Jordan is an icon of a proposal that enhances the conspicuously murky swamps of our condition.

The Lord not only grasps the possibilities, but even makes the waters cheerful [so in all oriental icons, which accentuate elegant volutes].

But the question remains. How can our Lord come alongside an indistinct crowd of sinners and stragglers seeking redemption?

In each of them Jesus saw a talent emerge.

And we are at the lowest point on earth - 400 metres below sea level.

It is precisely this leap of quality that distinguishes sophisticated idealism or simplistic religiosity - even cloaked in great things - from any quest for Faith.

The Son reveals divine Life, which bursts forth shattering expectations.

It unceasingly manifests itself as a friend. Unconscious face that does not destroy but draws near, to bring out the stifled possibilities.

Because God does not crush, he does not humiliate our hidden inclinations and resources, nor does he add unbearable burdens.

He is not a King of the submissive and weary.

He enters into a muddy reality, for it is filled with points of tension.

Thus he prepares our developments, and desires to grow - producing paths though interrupted, but finally the unexpected flower.

Now, at last, it is possible for each one to respond in a simple way to the spousal invitation: 'Do you want to unite your life to Mine?

Only that which is dehumanising does not concern our eternal side.

Any divine Gift passes through the 'flesh': the condition of the person as he is, even in the concreteness of his minimal or insecure actions.

The genuine rawness of our investigation of the true, the good and the beautiful passes - as in Jesus - through paths to be corrected over time, trial and error.

There is nothing wrong with that: only diamonds do not sprout.

Even Leonardo Da Vinci wrote that 'all our convictions begin with feelings. Not from crystalline, self-contained thoughts, but from a weaker language.

We are then introduced to a constant Exodus spirituality, which, however, is oriented towards the freedom of the Promised Land, the Home that is truly ours.

It is here - we perceive within - the outpouring of the intrinsic Centre, the personal Core, the founding Eros that calls.

Presence that detests the cage of patterns, approaching the rare, unusual (nothing grandiose) Irrepeatability that we are.

In all of this, awakening interest, and real, passionate life, which is not 'immune', nor definitive.

I mean, it happens even with God, to make a mistake.

We get back up, because that humus nourishes - and in the varied experience lurks - an opportunity, a knowledge, a skill, a greater authenticity: an added value.

The Father's call remains foreign both to the usual ideas of the verticism of objectives, and to adult mechanisms of purification - not aimed at ordinary existence (typical of philosophical or moralistic asceticism).

So the Baptism in Spirit is a Light - for us an inner increase, a sublimation of self-awareness and one's goal.

No longer a pale goal, only adjusted to roles, procedures, positions that the person does not feel are their own.

The very "rending of the heavens" no longer sealed by a (severe) distance or cultural paradigm, speaks of a now uninterrupted and growing Communication of the divine with human nature.

Exploring we can err, in both senses.

But far worse is to feel dull and unmotivated, and to act according to fixed nomenclatures and concatenations, i.e. by calculation.

In fact, in ancient religious culture, perfection and unworthiness are incomprehensible.

Conversely, in Christ we return to the moment of Creation, where "the olive tree" tells of a harmony rebuilt precisely on the limits of sin.

Gen 8:21: "I will curse no more, for the instinct of the human heart is inclined to evil from adolescence".

Here is the Dove, the new symbol of the Spirit.

A clear figure and virtue of concert, of recovery, which animates the believer - who is no longer called to titanic efforts, nor obliged to reproduce futile clamour that he does not want and does not belong to him.

Ancient kingdoms expressed and aroused the aggressive energy of beasts.

The authentic woman and man, on the other hand, are the revolutionaries of caress, of kindness granted even to their own and others' limits.

Faithful, not of the sphere but of the polyhedron: no longer the hard and safe ones, planted on trivial self-celebratory euphorias.

In the school of the great Precursor, Jesus had noticed the proliferation of coruscating and 'spiritual' frictions that arose between (the Baptist's) pupils - who competed to set up the Kingdom.

Having assessed the vacuous coldness and the danger of homologation - the new Rabbi definitely understands that the worst disease of people is not having humanising impulses.

Impulses that are perhaps ill-tempered, certainly, but that predispose not to Exodus, but to a sort of climb in predictable stages, with perpetual pause; at room-temperature.

Here, no shady side becomes new wealth for all.

For this reason, on "the Mount" we proclaim no commanded "No" that denies our ardours - but rather, Beatitudes.

They open breath and all existence. Even of the uncertain.

In short, not yet knowing who we are and where we are going means the possibility of reinventing ourselves.

Thus we learn to love our limitations and the many limiting conditions: they remind us of the Jordan.

The earth needs Light, but the Light needs the earth. They are an expression of the New Covenant.

To internalise and live the message:

Have you ever met a wise spiritual companion who, instead of rushing you into his or her solution, teaches you to love your limits, knowing that sooner or later they will surprise and astound both you and him or her?

A new beginning, and how to remain in the Father's favour

According to the account of the Evangelist Matthew (3:13-17), Jesus came from Galilee to the River Jordan to be baptized by John; indeed people were flocking from all over Palestine to hear the preaching of this great Prophet and the proclamation of the coming of the Kingdom of God and to receive Baptism, that is, to submit to that sign of penance which calls for conversion from sin.

Although it was called “Baptism” it did not have the sacramental value of the rite we are celebrating today; as you well know, it was actually with his death and Resurrection that Jesus instituted the sacraments and caused the Church to be born. What John administered was a penitential act, a gesture of humility to God that invited a new beginning: by immersing themselves in the water, penitents recognized that they had sinned, begged God for purification from their sins and were asked to change wrong behaviour, dying in the water, as it were, and rising from it to new life.

For this reason, when John the Baptist saw Jesus who had come to be baptized queuing with sinners he was amazed; recognizing him as the Messiah, the Holy One of God, the One who is without sin, John expressed his consternation: he, the Baptist, would himself have liked to be baptized by Jesus. But Jesus urged him not to put up any resistance, to agree to do this act, to do what is fitting “to fulfil all righteousness”.

With these words Jesus showed that he had come into the world to do the will of the One who had sent him, to carry out all that the Father would ask of him. It was in order to obey the Father that he accepted to be made man. This act reveals, first of all, who Jesus is: he is the Son of God, true God as the Father; he is the One who “humbled himself” to make himself one of us, the One who was made man and who accepted to humble himself unto death on a cross (cf. Phil 2:7).

The Baptism of Jesus, which we are commemorating today, fits into this logic of humility and solidarity: it is the action of the One who wanted to make himself one of us in everything and who truly joined the line of sinners; he, who knew no sin, let himself be treated as a sinner (cf. 2 Cor 5:21), to take upon his shoulders the burden of the sin of all humanity, including our own sin. He is the “servant” of Yahweh of whom the Prophet Isaiah spoke in the First Reading (cf. 42:1). His humility is dictated by the desire to establish full communion with humanity, by the desire to bring about true solidarity with man and with his human condition.

Jesus’ action anticipates the Cross, his acceptance of death for man’s sins. This act of abasement, by which Jesus wanted to comply totally with the loving plan of the Father and to conform himself with us, expresses the full harmony of will and intentions that exists between the Persons of the Most Holy Trinity. For this act of love, the Spirit of God revealed himself and descended to alight upon Jesus as a dove, and at that moment the love which unites Jesus to the Father was witnessed to all who were present at the Baptism by a voice from Heaven that everyone heard.

The Father reveals openly to human beings, to us, the profound communion that binds him to the Son: the voice that resounds from on high testifies that Jesus is obedient to the Father in all things and that this obedience is an expression of the love that unites them to each other.

Therefore the Father delights in Jesus, for he recognizes in the Son’s behaviour the wish to obey his will in all things: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased” (Mt 3:17). And these words of the Father also allude, in advance, to the victory of the Resurrection and tell us how we must live in order to please the Father, by behaving like Jesus.

[Pope Benedict, homily in the Sistine Chapel, 9 January 2011]

Call to intimate union with divine life

"You are my beloved Son; in You I am well pleased".

2. The ceremony, which on this typical Sunday of the liturgical cycle we are about to perform, calls to our mind certain truths of essential importance in Christian doctrine.

First of all, it recalls the episode - read in today's Gospel - of the Baptism of Jesus, who wished to include himself, as a penitent, among the followers of John the Baptist in order to receive water baptism from him. Such a rite was a sign of penitence; but Jesus wanted to subject himself to it, to show openly that he accepted the religious message of the people of Israel, expressed in a conclusive way by the last of the Prophets. From Abraham to Moses, to Elijah, to Isaiah, through all the Prophets, up to John the Baptist, along the mysterious and dramatic "history of salvation" the "word of God" had walked with the Jewish people, until it led to the arcane voice from heaven that on Jesus, baptised by John, said: "You are my beloved Son; in you I am well pleased" (Lk 3:22). In Jesus, the Messiah awaited by the chosen people, the definitive transition from the Old to the New Testament took place, and John the Baptist was its austere and enlightened witness.

But today's Liturgy also and above all emphasises the value of the new Baptism, instituted by Jesus. John the Baptist, announcing the coming of the Messiah, said: 'One is coming who will baptise you in the Holy Spirit and fire'. Jesus, initiating the new 'economy' of salvation, tells the Apostles: 'All power in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Mt 28:18-19). This is the new and definitive Baptism, which eliminates from the soul the "original sin", inherent in human nature fallen through the rejection of love by the first two rational creatures, and restores to the soul the "sanctifying grace", that is, participation in the very life of the Holy Trinity. Every time Baptism is conferred, an amazing and marvellous event takes place; the rite is simple, but the meaning is sublime! The fire of God's creative and redeeming love burns and destroys sin and takes possession of the soul, which becomes the dwelling place of the Most High! The Evangelist St John affirms that Jesus has given us the power to become children of God, because from God we have been begotten (cf. Jn 1:12-13); and St Paul speaks repeatedly of our greatness and dignity as members of the Body of Christ (Col 2:19; Eph 3:11. 17. 19-22; 4:12).

3. Baptism is a supernatural gift, a radical transformation of human nature, the insertion of the soul into the very life of God, the concrete and personal realisation of the Redemption, and therefore consequently commits the baptised person to live in a new way, namely following Christ. It has never been easy to live as a Christian and even less so in modern society. The Church is happy to welcome these newly-baptised children; but she wants the parents, godparents and godmothers, and also the entire community, to take on the serious duties of good example, correct teaching and authentic Christian formation, so that the child in the gradual development of his or her existence may be faithful to his or her baptismal commitments.

4. St Augustine, recalling in the Confessions the episode of his Baptism, writes: 'In those days, all filled with extraordinary sweetness, I was not satisfied with considering the depth of your counsel for the salvation of the human race' (St Augustine, Confessiones, IX, ch. VI). This immense interior joy I also heartily wish for you and for your children, now and for ever, while I invoke the propitiatory intercession of Most Holy Mary, so that by her help the light and candour of Baptism, which these little ones now receive, may shine in them throughout their lives.

[Pope John Paul II, homily January 1983]

Dear Brothers and Sisters!

1. Today's liturgical feast of the Baptism of the Lord closes the Christmas season, which we observed this year with exceptional fervour and participation. Indeed, the Great Jubilee began on the Holy Night with the opening of the Holy Door in St Peter's.

This Christmas season has offered us a new occasion to recall the "fact" that occurred 20 centuries ago and definitively changed the course of history: Jesus' birth in Bethlehem.

In recalling Jesus' birth, we celebrated the great mystery of Redemption, to which we pay particular attention throughout the course of the Jubilee. The Son of God became man so that man could be raised to the dignity of God's adoptive son.

2. Today's feast of the Baptism of the Lord reminds us of this intimate union with the divine life.

[Pope John Paul II, Angelus 9 January 2000]

Justice of the Servant

This year’s liturgy offers us the event of the Baptism of Jesus according to the Gospel of Matthew (cf. 3:13-17). The Evangelist describes the dialogue between Jesus who asks to be baptized and John the Baptist who wants to prevent him and observes: “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” (v. 14). This decision by Jesus surprises the Baptist: in fact the Messiah does not need to be purified; indeed he is the one who purifies. But God is Holy. His ways are not ours and Jesus is God’s path, an unpredictable path. Let us remember that God is the God of surprises.

John had stated that there was an abyssal, unbridgeable difference between him and Jesus. I am not worthy to carry his sandals (cf. Mt 3:11), he had said. But the Son of God came precisely to fill this gap between man and God. If Jesus is completely on God’s side, he is also completely on the side of mankind and he reunites what was divided. This is why he answers John: “Let it be so now; for thus it is fitting for us to fulfil all righteousness” (v. 15). The Messiah asks to be baptized so that all righteousness be fulfilled, that God’s design which passes through filial obedience and solidarity with fragile and sinful mankind, be fulfilled. It is the path of humility and of God’s complete closeness to his children.

The prophet Isaiah also announces the righteousness of the Servant of God who fulfills his mission in the world with a style that is opposed to the worldly spirit. “He will not cry or lift up his voice, or make it heard on the street; a bruised reed he will not break, and a dimly burning wick he will not quench” (42:2-3). It is the attitude of meekness — the attitude of simplicity, of respect, of moderation and of hiddeness that is still asked today of the Lord’s disciples. How many — it is sad to say — how many of the Lord’s disciples boast that they are disciples of the Lord. Those who boast are not good disciples of the Lord. The good disciple is humble, meek, one who does good unobtrusively. In missionary work, the Christian community is called to approach others always offering and not imposing, bearing witness, sharing the concrete life of the people.

As soon as Jesus was baptized in the River Jordan, the heavens were opened and the Holy Spirit alighted on him like a dove, as a voice from heaven said: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased” (Mt 3:17). We rediscover our own Baptism in the Feast of the Baptism. Just as Jesus is the Beloved Son of the Father, we too, reborn by water and the Holy Spirit, know we are loved children — the Father loves us all! —, the object of God’s satisfaction, brothers and sisters of many brothers and sisters, assigned with a great mission to bear witness and proclaim the Father’s boundless love to all mankind.

This Feast of the Baptism of Jesus reminds us of our own Baptism. We too were reborn in Baptism. In Baptism the Holy Spirit came down to remain within us. This is why it is important to know the date of our Baptism. We know our date of birth, but we do not always know the date of our Baptism. Certainly some of you do not know it.... Homework to do: when you return [home] ask: when was I baptized? When was I baptized? And celebrate the date of your Baptism in your heart, every year. Do it. This also does justice to the Lord who was so kind to us.

May Mary Most Holy help us to increasingly understand the gift of Baptism and to live it consistently in everyday situations.

[Pope Francis, Angelus, 12 January 2020]

Baptism of the Lord: by trial and error, like us

The platform that makes the breakthrough

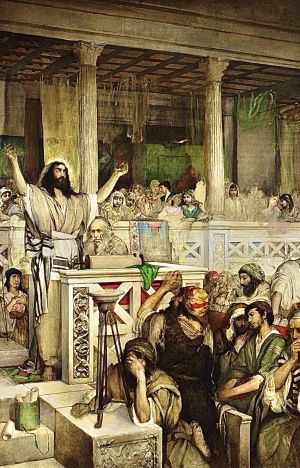

In the Synagogue and from the precipice

(Lc 4:14-22)

In ancient Israel, the patriarchal family, clan and community were the basis of social coexistence.

They ensured the transmission of the nation identity and provided protection for the afflicted.

But at the time of Jesus, Galilee was subject to the segregation dictated by Herod's policies, and suffered from the oppression of official religiosity.

The political and economic situation forced people to retreat into material and individual problems or those of small family.

A situation that was leading the least protected sections of the population to collapse.

Instead, Jesus wants to return to the Father's Dream: the ineradicable one of Fraternity, the only seal to salvation history.

Thus, according to Lk the first time Jesus enters a synagogue he makes a mess.

He does not go to pray, but to Teach what the Grace of God is [the one not weakened by chicanery or false instructions] in the real existence of people.

He chose a passage that reflected the situation of his people, oppressed by the power of the rulers, who were making the weak suffer confusion and poverty.

But his First Reading disregards the liturgical calendar.

He then dares to preach in his own way and personalizes the passage from Isaiah, from which he allows himself to censor the verse announcing God's “vengeance”.

So neither does He proclaim the expected passage of the Law.

Moreover, for the Son of God, the Spirit is not revealed in the extraordinary phenomena of the cosmos, but in the Year of Grace [«a year acceptable to the Lord»: v.19].

Is it possible that the divine likeness could manifest itself in a man who is considerate towards the less fortunate, who disregards official customs, does not believe in retaliation, and displays forms of uncontrolled spontaneity?

It is a reminder to us.

Like the Master, instead of reasoning with induced thoughts and being sequestered by the heaviness of rejections and fears, in Him we begin to think with the empathic codes of our Calling, which breaks through.

The unrepeatable and wide-ranging Vision-Relation (v.18a) - without reduction - then becomes strategic, because it possesses within itself the appeal of the radical essence, and all the resources to solve the real problems.

To listen to the proclamation of the Gospels (v.18b) is to listen to the echo of oneself and the people considered insignificant: intimate and fraternal choice.

And to be in it without the dead leaves of one-sidedness - by wandering freely in that same Appeal; not neglecting precious parts of oneself, nor amputating eccentricities, or the intuition proper to the subaltern classes.

In this way, we remain in the instinct to be and do happy, without ever allowing ourselves to be imprisoned by the craving for security on the side: a stagnant quest.

The Kingdom in the Spirit (cf. vv.14.18) knows what we need. It has ceased to be a goal of mere future.

It is the surprise that Christ arouses in us through his Dream, around his proposal with an extra gear.

The Lord does not neglect us: He extinguishes accusatory brooding and creatively redesigns.

He gives birth again and motivates, recovers dispersions and reinforces the plot.

It is divine because it is personal and social, the new Energy, empowered to create the authentic man.

This is the platform that works the breakthrough.

[Weekday Liturgy, January 10]

Jesus in the synagogue. Two Names of God

Lk 4:24-30 (16-37)

Jesus' transgressions and ours (reinforcing the plot)

(Lk 4:14-22)

"The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, therefore he has anointed me to proclaim the Good News to the poor" (Lk 4:18).

In ancient Israel, the patriarchal family, clan and community were the basis of social coexistence.

They guaranteed the transmission of the identity of the people and provided protection for the afflicted.

Defending the clan was also a concrete way of confirming the First Covenant.

But at the time of Jesus, Galilee suffered both the segregation dictated by Herod Antipas' policy and the oppression of official religiosity.

The ruler's spineless collaborationism had increased the number of homeless and unemployed.

The political and economic situation forced people to retreat into material and individual problems or those of a small family.

At one time, the identity glue of clan and community guaranteed a (domestic) character of a nation of solidarity, expressed in the defence and relief given to the less well-off of the people.

Now, this fraternal bond was weakened, a little congealed, almost contradicted - also due to the strict attitude of the religious authorities, fundamentalist and lovers of a saccharine purism, opposed to mixing with the less well-off classes.

The [written and oral] Law ended up being used not to favour the welcoming of the marginalised and needy, but to accentuate detachment and ghettoisation.

Situations that were leading to the collapse of the least protected sections of the population.

In short, traditional devotion - loving the alliance between throne and altar - instead of strengthening the sense of community was being used to accentuate hierarchies; as a weapon to legitimise a whole mentality of exclusions (and confirm the imperial logic of divide and rule).

Instead, Jesus wants to return to the Father's Dream: the ineliminable one of fraternity, the only seal to salvation history.

That is why his non-avoidable criterion was to link the Word of God to the life of the people, and in this way overcome divisions.

Thus, according to Lk, the first time Jesus enters a synagogue he messes up.

He does not go there to pray, but to teach what God's Grace (undefiled by chicanery and false teachings) is in the real existence of people.

He chooses a passage that precisely reflects the situation of the people of Galilee, oppressed by the power of the rulers, who were making the weak suffer confusion and poverty.

But his first Reading does not take into account the liturgical calendar.

Then he dares to preach in his own way and personalising the passage from Isaiah, from which he allows himself to censor the verse announcing God's vengeance.

Then he does not even proclaim the expected passage of the Law.

And he poses as if he were the master of the place of worship - in fact he is: the Risen One who 'sits' is teaching his [still Judaizing] people.

Moreover - we understand from the tone of the Gospel passage - for the Son of God the Spirit is not revealed in the extraordinary phenomena of the cosmos, but in the Year of Grace ("a year acceptable to the Lord": v.19).

It is divine because it is personal and social, the new energy that creates the authentic man.

This is the platform that works the turning point.

It becomes an engine, a motive and context, for a transformation of the soul and of relationships - at that time weighed down by servility, even theological [of merits].

In a warp of vital relationships, the better understanding of the Gift becomes a springboard for a harmonious future of liberation and justice.

Christ believes that the Father's Kingdom arises by making the present, then mired in oppression, anguish and slavery, grow from within.

The Tao Tê Ching (XLVI) says: "When the Way is in force in the world, swift horses are sent to fertilise the fields".

The emancipation offered by the Spirit is addressed not to the great, but precisely to those who suffer forms of need, defect and penury: in Jesus... now all open to the jubilee figure of the new Creation.

In short, there seems to be total antagonism and unsuitability between the Lord and the practitioners of traditional religion - heavy-handed, selective, devoted to legalisms and reprisals; pyramidal, with no way out.

Obviously, both leaders and customaries ask themselves - on a ritual and venerable basis: is it possible that the divine likeness could manifest itself in a man who is considerate towards the less affluent, who disregards official customs, does not believe in reprisals, and displays forms of uncontrolled spontaneity?

This is a reminder for us. The person of authentic Faith does not allow himself to be conditioned by habitual, useless and quiet conformities.

The common thought - habituated and agreed upon but subtly competitive - becomes a backwards energy, too normal and swampy; not propulsive for the personal and social soul.If, on the other hand, we allow ourselves to be accompanied by the Dream of a super-eminent gestation from the Father, we will be animated through the regal and sacred Presence that directs us to fly over repetitions, or selections, marginalisations and fallacious recriminations.

As if we move our being into a horizon and a world of friendly relations that then acts as a magnet to reality and anticipates the future.

Like the Master and Lord, instead of reasoning with induced thoughts and allowing ourselves to be sequestered by the heaviness of rejections and fears, let us begin to think with the images of personal Vocation, with the empathic codes of our bursting Calling.

The unknown evolutionary resources that are triggered, immediately unravel a network of paths that the "locals" may not like, but avoid the perennial conflict with missionary identity and character.

The Vision-Relation (v.18a) unrepeatable and wide-meshed - without reduction - then becomes strategic, because it possesses in itself the call of the Quintessence, and all the resources to solve the real problems.

To listen to the proclamation of the Gospels (v.18b) is to listen to the echo of oneself and of the little people: an intimate and social choice.

And to be in it without the dead leaves of one-sidedness - to wander freely in that same Proclamation; not neglecting precious parts of oneself, nor amputating eccentricities, or the intuition proper to the subordinate classes.

This is to be able to manifest the quiet Root (but in its energetic state), our Character (in the lovable, non-separatist Friend) - to avoid stultifying it with another bondage.

All in the instinct to be and do happy, never allowing ourselves to be imprisoned by the lust for security on the side; stagnant pursuit.

The Kingdom in the Spirit (cf. vv.14.18) - who knows what we need - has ceased to be a goal of mere futurity.

It is the surprise that Christ arouses in us around his proposal with an extra gear.

He does not neglect us: he extinguishes accusatory brooding and creatively redesigns.

He gives birth again and motivates, recovers dispersions, and strengthens the plot.

To internalise and live the message:

How do I connect the Faith with the cultural and social situation?

What is Christ's Today with your Today, in the Spirit?

What is your form of apostolate that frees brothers and sisters from the debasement of dignity and promotes them?

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me (et vult Cubam)

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me; therefore he has anointed me and sent me forth to proclaim a glad tidings" (Lk 4:18). Every minister of God must make these words spoken by Jesus of Nazareth his own life. Therefore, as I stand here among you, I want to bring you the good news of hope in God. As a servant of the Gospel, I bring you this message of love and solidarity that Jesus Christ, with his coming, offers to people of all times. It is neither an ideology nor a new economic or political system, but a path of peace, justice and authentic freedom.

4. The ideological and economic systems that have succeeded one another in recent centuries have often emphasised confrontation as a method, since they contained in their programmes the seeds of opposition and disunity. This has deeply conditioned the conception of man and relations with others. Some of these systems also claimed to reduce religion to the merely individual sphere, stripping it of any social influence or relevance. In this sense, it is worth remembering that a modern state cannot make atheism or religion one of its political orders. The State, far from any fanaticism or extreme secularism, must promote a serene social climate and appropriate legislation that allows each person and each religious denomination to live their faith freely, express it in the spheres of public life and be able to count on sufficient means and space to offer their spiritual, moral and civic riches to the life of the nation.

On the other hand, in various places, a form of capitalist neo-liberalism is developing that subordinates the human person and conditions the development of peoples to the blind forces of the market, burdening the less favoured peoples with unbearable burdens from its centres of power. Thus it often happens that unsustainable economic programmes are imposed on nations as a condition for receiving new aid. In this way we witness, in the concert of nations, the exaggerated enrichment of a few at the price of the growing impoverishment of the many, so that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

5. Dear brothers: the Church is a teacher in humanity. Therefore, in the face of these systems, she proposes the culture of love and life, restoring to humanity the hope and transforming power of love, lived in the unity willed by Christ. This requires a path of reconciliation, dialogue and fraternal acceptance of one's neighbour, whoever they may be. This can be said of the Church's social Gospel.

The Church, in carrying out its mission, proposes to the world a new justice, the justice of the Kingdom of God (cf. Mt 6:33). On several occasions I have referred to social issues. It is necessary to keep talking about them as long as there is injustice in the world, however small it may be, since otherwise the Church would not prove faithful to the mission entrusted to her by Jesus Christ. What is at stake is man, the person in the flesh. Even if times and circumstances change, there are always people who need the voice of the Church to acknowledge their anguish, pain and misery. Those who find themselves in such situations can be assured that they will not be defrauded, for the Church is with them and the Pope embraces, with his heart and his word of encouragement, all those who suffer injustice.

(John Paul II, after being applauded at length, added)

I am not against applause, because when you applaud the Pope can rest a little.

The teachings of Jesus retain their vigour intact on the threshold of the year 2000. They are valid for all of you, my dear brothers. In the search for the justice of the Kingdom, we cannot stop in the face of difficulties and misunderstandings. If the Master's invitation to justice, service and love is accepted as Good News, then hearts are enlarged, criteria are transformed and the culture of love and life is born. This is the great change that society awaits and needs; it can only be achieved if first the conversion of each person's heart takes place as a condition for the necessary changes in the structures of society.

6. "The Spirit of the Lord has sent me to proclaim release to the captives (...) to set at liberty those who are oppressed" (Lk 4:18). The good news of Jesus must be accompanied by a proclamation of freedom, based on the solid foundation of truth: "If you remain faithful to my word, you will indeed be my disciples; you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free" (John 8:31-32). The truth Jesus refers to is not just the intellectual understanding of reality, but the truth about man and his transcendent condition, his rights and duties, his greatness and limitations. It is the same truth that Jesus proclaimed with his life, reaffirmed before Pilate and, by his silence, before Herod; it is the same truth that led him to the salvific cross and glorious resurrection.

Freedom that is not grounded in truth conditions man to such an extent that it sometimes makes him the object rather than the subject of the social, cultural, economic and political context, leaving him almost totally deprived of initiative with regard to personal development. At other times, this freedom is individualistic and, taking no account of the freedom of others, locks man into his own selfishness. The conquest of freedom in responsibility is an unavoidable task for every person. For Christians, the freedom of God's children is not only a gift and a task; its attainment also implies an invaluable witness and a genuine contribution to the liberation of the entire human race. This liberation is not reduced to social and political aspects, but reaches its fullness in the exercise of freedom of conscience, the basis and foundation of other human rights.

(Responding to the invocation raised by the crowd: "The Pope lives and wants us all to be free!", John Paul II added:)

Yes, he lives with that freedom to which Christ has set you free.

For many of today's political and economic systems, the greatest challenge continues to be to combine freedom and social justice, freedom and solidarity, without any of them being relegated to a lower level. In this sense, the Social Doctrine of the Church constitutes an effort of reflection and a proposal that seeks to enlighten and reconcile the relationship between the inalienable rights of every man and social needs, so that the person may fulfil his deepest aspirations and his own integral realisation according to his condition as a child of God and citizen. Consequently, the Catholic laity must contribute to this realisation through the application of the Church's social teachings in the various environments, open to all people of good will.

7. In the Gospel proclaimed today, justice appears intimately linked to truth. This is also observed in the lucid thinking of the Fathers of the Fatherland. The Servant of God Father Félix Varela, animated by Christian faith and fidelity to his priestly ministry, sowed in the hearts of the Cuban people the seeds of justice and freedom that he dreamed of seeing germinate in a free and independent Cuba.José Martí's doctrine of love among all people has profoundly evangelical roots, thus overcoming the false conflict between faith in God and love and service to the homeland. Martí writes: 'Pure, unselfish, persecuted, martyred, poetic and simple, the religion of the Nazarene has seduced all honest men... Every people needs to be religious. It must be so not only in its essence, but also for its utility.... A non-religious people is doomed to die, for nothing in it nourishes virtue. Human injustice despises it; it is necessary for heavenly justice to guarantee it'.

As you know, Cuba possesses a Christian soul, and this has led it to have a universal vocation. Called to overcome its isolation, it must open up to the world, and the world must draw closer to Cuba, to its people, to its children, who undoubtedly represent its greatest wealth. The time has come to take the new paths that the times of renewal in which we live demand, as we approach the Third Millennium of the Christian era!

8. Dear brothers: God has blessed this people with authentic formators of the national conscience, clear and firm exponents of the Christian faith, which is the most valid support of virtue and love. Today the Bishops, together with priests, consecrated men and women and the lay faithful, strive to build bridges to bring minds and hearts closer together, propitiating and consolidating peace, preparing the civilisation of love and justice. I am here among you as a messenger of truth and hope. That is why I wish to repeat my call to allow yourselves to be enlightened by Jesus Christ, to accept without reserve the splendour of his truth, so that all may follow the path of unity through love and solidarity, avoiding exclusion, isolation and confrontation, which are contrary to the will of the God-Love.

May the Holy Spirit enlighten with his gifts all those who have different responsibilities towards this people, whom I hold in my heart. May the "Virgen de la Caridad de El Cobre", Queen of Cuba, obtain for her children the gifts of peace, progress and happiness.

This wind today is very significant, because the wind symbolises the Holy Spirit. "Spiritus spirat ubi vult, Spiritus vult spirare in Cuba". The last words are in Latin because Cuba also belongs to the Latin tradition. Latin America, Latin Cuba, Latin language! "Spiritus spirat ubi vult et vult Cubam'. Goodbye.

(John Paul II, homily "José Martí" Square Havana 25 January 1998)

Person, extemporaneity, synagogues

Two Names of God

(Lk 4:21-30)

Today's Gospel - taken from the fourth chapter of St Luke - is a continuation of last Sunday's Gospel. We find ourselves again in the synagogue of Nazareth, the town where Jesus grew up and where everyone knew him and his family. Now, after a period of absence, He has returned in a new way: during the Sabbath liturgy, He reads a prophecy from Isaiah about the Messiah and announces its fulfilment, implying that the word refers to Him, that Isaiah has spoken of Him. This fact provokes the bewilderment of the Nazarenes: on the one hand, "all bore witness to him and were amazed at the words of grace that came out of his mouth" (Lk 4:22); St Mark reports that many said: "Where do these things come from him? And what wisdom is this that has been given him?" (6:2). On the other hand, however, his countrymen know him all too well: 'He is one like us', they say, 'His pretension can only be presumption' (cf. The Infancy of Jesus, 11). "Is not this the son of Joseph?" (Lk 4:22), as if to say: a carpenter from Nazareth, what aspirations can he have?

Precisely knowing this closure, which confirms the proverb "no prophet is welcome in his own country", Jesus addresses the people in the synagogue with words that sound like a provocation. He mentions two miracles performed by the great prophets Elijah and Elisha in favour of non-Israelites, to show that sometimes there is more faith outside Israel. At that point the reaction is unanimous: everyone gets up and throws him out, and even tries to throw him off a cliff, but he calmly sovereignly passes through the angry people and leaves. At this point the question arises: why did Jesus want to provoke this rupture? At first, the people admired him, and perhaps he could have obtained some consensus... But this is precisely the point: Jesus did not come to seek the consensus of men, but - as he will say at the end to Pilate - to "bear witness to the truth" (Jn 18:37). The true prophet does not obey anyone other than God and puts himself at the service of the truth, ready to pay for it himself. It is true that Jesus is the prophet of love, but love has its own truth. Indeed, love and truth are two names of the same reality, two names of God. In today's liturgy, these words of St Paul also resonate: "Charity ... does not boast, is not puffed up with pride, is not disrespectful, does not seek its own interest, is not angry, does not take account of evil received, does not rejoice in injustice but rejoices in the truth" (1 Cor 13:4-6). Believing in God means renouncing one's prejudices and accepting the concrete face in which He revealed Himself: the man Jesus of Nazareth. And this way also leads to recognising and serving Him in others.

In this, Mary's attitude is illuminating. Who more than she was familiar with the humanity of Jesus? But she was never as scandalised by it as the people of Nazareth. She kept the mystery in her heart and knew how to welcome it again and again, on the path of faith, until the night of the Cross and the full light of the Resurrection. May Mary also help us to tread this path with fidelity and joy.

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 3 February 2013].

Jesus is annoying and generates suspicion in those who love external schemes, because he proclaims only Jubilee, instead of harsh confrontation and vengeance.

In the synagogue his village is puzzled by this overly understanding love - just what we need.

The place of worship is where believers have been brought up backwards!

Their grumpy character is the unripe fruit of a hammering religiosity, which denies the right to express ideas and feelings.

The 'synagogal' code has produced fake believers, conditioned by a disharmonious and split personality.

Even today and from an early age, this intimate laceration manifests itself in the over-controlling of openness to others.

Consequence: an accentuation of youthful uncertainty - under which who knows what smoulders - and a rigid character as adults.

In short, religious hammering that does not make the leap of faith blocks us, prevents us from understanding, and pollutes our whole life.

Even in Jesus' time, archaic teaching exacerbated nationalism, the very perception of trauma or violation, and paradoxically the very caged situations from which one wanted to get out.

Exclusive spirituality: it is empty - crude or sophisticated.

Selective thinking is the worst disease of worldviews - which are then always telling us how we should be.

So in concrete life, not a few believers prefer to have friends without conformist blindness or the same bonds of belonging.

On closer inspection, even the most devout lay realities manifest a pronounced and strange dichotomy of relationships - tribal and otherwise.

Pope Francis expressed it crisply:

"It is a scandal that of people who go to church, who are there every day and then live hating others and speaking ill of people: it is better to live as an atheist than to give a counter-witness to being a Christian".

The real world awakens and stimulates flexibility of standards, it does not inculcate some old-fashioned, hypnosis-like truism.

Today's global reality helps to blunt the edges of conventicle [which have their regurgitations, in terms of seduction and sucking].

In the face of such beliefs and illusions, the Prophet marks distance; he works to spread awareness, not reassuring images - nor disembodied ideas.

But the critical heralds violently irritate the crowd of regulars, who suddenly turn from curiosity to vengeful indignation.

As in the village, so - we read in a watermark - in the Holy City [Mount Zion] from which they immediately want to throw you down (Lk 4:29).

Wherever there is talk of a real person and eternal dreams: his, not others'.

In the hostility that surrounds them, the Lord's intimates openly challenge normalised beliefs, acquired from the environment and not reworked.

For them, it is not only the calculated analogy to a petty outline that counts. They see other goals and do not just want to 'get there'.

If they are overwhelmed, they leave behind them that trail of intuition that will sooner or later make both harmful clansmen and useless opportunists reflect.

Thus, in Friends and Brothers it is the Risen One himself who escapes. And he resumes the path, crossing those who want to do him in (v. 30) for reasons of self-interest or neighbourhood advantage.

At all times, the witnesses make one think: they do not seek compliments and pleasant results, but recover the opposite sides and accept the happiness of others.

They know that Oneness must run its course: it will be wealth for all, and on this point they do not let themselves be inhibited by nomenclature.

Though surrounded by the envious and deadly hatred of cunning idiots and established synagogues, they proclaim Love in Truth - neither burine hoaxes (approved as empty) nor ulterior motives (solid utility).

In fact, without milking and shearing the uninformed, such missionaries give impetus to the courage and growth of others, to the autonomy of choices.

All this, by fostering the coexistence of the invisible and despised; in an atmosphere of understanding and spontaneity.They love the luxuriance of life, so they discriminate between religion and Faith: they do not stand as repeaters of doctrines, prescriptions, customs.

Based on the Father's personal experience, the inspired faithful value different approaches, creating an unknown esteem.

They confront young sectarian monsters [the Pontiff would say], old marpions and their fences, with an open face, advocating new attitudes - different ways of relating to God.

Not to add proselytes and consider themselves indispensable.

Even though 'at home' (v. 24) they are inconvenient characters for the ratified mentality, the none-Prophets make Jesus' personalism survive, wrenching it from those who want it dormant and sequestered.

Like Him, at the risk of unpopularity and without begging for approval.

With the scars of what is gone, for a new Journey.

To internalise and live the message:

In the 'homeland' are you considered a local child, or a prophet? A ratified character, or uncomfortable? In fashion, or unpopular?

Is your testimony transgressive or conformist? Does it make Jesus' personalism survive, wrenching it from those who want it dormant and sequestered?

God wants faith, they want miracles: God for their own benefit

Last Sunday, the liturgy had proposed to us the episode in the synagogue of Nazareth, where Jesus reads a passage from the prophet Isaiah and at the end reveals that those words are fulfilled "today", in Him. Jesus presents Himself as the one on whom the Spirit of the Lord has rested, the Holy Spirit who consecrated Him and sent Him to fulfil the mission of salvation on behalf of humanity. Today's Gospel (cf. Lk 4:21-30) is the continuation of that story and shows us the amazement of his fellow citizens at seeing that one of their countrymen, "the son of Joseph" (v. 22), claims to be the Christ, the Father's envoy.

Jesus, with his ability to penetrate minds and hearts, immediately understands what his countrymen think. They think that, since He is one of them, He must prove this strange "claim" of His by performing miracles there, in Nazareth, as He did in the neighbouring countries (cf. v. 23). But Jesus does not want and cannot accept this logic, because it does not correspond to God's plan: God wants faith, they want miracles, signs; God wants to save everyone, and they want a Messiah for their own benefit. And to explain God's logic, Jesus brings the example of two great ancient prophets: Elijah and Elisha, whom God had sent to heal and save people who were not Jewish, from other peoples, but who had trusted his word.

Faced with this invitation to open their hearts to the gratuitousness and universality of salvation, the citizens of Nazareth rebel, and even assume an aggressive attitude, which degenerates to the point that "they got up and drove him out of the city and led him to the edge of the mountain [...], to throw him down" (v. 29). The admiration of the first moment turned into an aggression, a rebellion against Him.

And this Gospel shows us that Jesus' public ministry begins with a rejection and a threat of death, paradoxically precisely from his fellow citizens. Jesus, in living the mission entrusted to him by the Father, knows well that he must face fatigue, rejection, persecution and defeat. A price that, yesterday as today, authentic prophecy is called upon to pay. The harsh rejection, however, does not discourage Jesus, nor does it stop the journey and the fruitfulness of his prophetic action. He goes on his way (cf. v. 30), trusting in the Father's love.

Even today, the world needs to see in the Lord's disciples prophets, that is, people who are courageous and persevering in responding to the Christian vocation. People who follow the 'thrust' of the Holy Spirit, who sends them to announce hope and salvation to the poor and excluded; people who follow the logic of faith and not of miracles; people dedicated to the service of all, without privileges and exclusions. In short: people who are open to accepting the Father's will within themselves and are committed to faithfully witnessing it to others.

Let us pray to Mary Most Holy, that we may grow and walk in the same apostolic ardour for the Kingdom of God that animated Jesus' mission.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 3 February 2019].

Liberation from quietism and automatic mentality

(Lk 4:31-37)

In the third Gospel, the first signs of the Lord are the quiet escape from the threats of death (agitated by his people!) and the healing of the possessed.

In such a way of narrating the story of Jesus, Lk indicates the priorities that his communities were living: first of all, there was a need to suspend the intimate struggles, inculcated by the Judaizing tradition and its 'knowing how to be in the world'.

In the stubborn and conformist village of Nazareth, the Master is unable to communicate his newness, and is forced to change residence.

He does not resign himself, on the contrary: Capernaum was at the crossroads of important roads, which facilitated contacts and dissemination.Among people from all walks of life, the Son of God wanted to create a consciousness that was highly critical of the homologated doctrines of religious leaders.

He did not mechanically quote the - modest - teachings of the authorities, but started from his own life experience and living relationship with the Father.

He did not seek support, neither for safe living nor for the proclamation - thus he created clear minds and an unusual quiver.

In this way, he suspended in souls the usual doubts of conscience, the usual battles inoculated by the customary-doctrinal-moral cloak, and his inner lacerations.

In a transparent and totally non-artificial manner, Christ [in his] still escapes evil and struggles against the plagiarising, reductive forces of our personality.

In the mentality of automatisms devoid of personal faith, it seemed at the time that one almost had to submit to the powers of external conviction.

All this to avoid being marginalised by the 'nation' [and by 'groups' regulated on conformity].

This also applies to us.

The duty to participate in collective rituals - here the Sabbath in the synagogue - risks dampening the intimate nostalgia for "ourselves" that provides nourishment for vocational exceptionality.

Originality in the history of salvation which, on the contrary, we could become, without the ball and chain of certain rules of quiet living, to the minimum - rhythm of customary social moments and symbolic days [sometimes emptied of meaning].

(All in the scruffy, mechanical ways that we know by heart, and no longer want, because we feel they do not make us reach a higher level).

The Master in us still faces the power that reduces people to the condition of ease without originality: a grey, perpetual trance allergic to differences.

Apathy that produces swamps and early camps, where no one protests but neither is surprised.

In the Gospel, the person who suddenly sparks sparks was always a quiet assembly-goer, who wearily dragged his spiritual life in small, colourless circles, lacking in breadth and rhythm.

But the Word of the Lord has a real charge in it: the power of the bliss of living, of creating, of loving in truth - which does not hate eccentric characteristics.

Where such a call comes, all the demons you don't expect are unmasked and leap out of their lairs [previously simulated, agreed upon, artificially homologated].

He who meets Christ is toppled from his abject seat, sitting upright; he sees his certainties thrown to the wind

Reversal that allows hidden or repressed facets to play their part - even if they are not 'as they should be'.

In short, the Gospel invites us to embrace all that is in us, as it is, unmitigated; multiplying our energies - for within lurks the best of our Call to personal Mission.