1. In the Gospels we find another fact that attests to Jesus' consciousness of possessing divine authority, and the persuasion that the evangelists and the early Christian community had of this authority. In fact, the Synoptics agree in saying that Jesus' listeners "were amazed at his teaching, because he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes" (Mk 1:22; Mt 7:29; Lk 4:32). This is valuable information that Mark gives us from the very beginning of his Gospel. It attests to the fact that the people had immediately grasped the difference between Christ's teaching and that of the Israelite scribes, and not only in the manner, but in the very substance: the scribes based their teaching on the text of the Mosaic Law, of which they were the interpreters and commentators; Jesus did not at all follow the method of a "teacher" or a "commentator" of the ancient Law, but behaved like a legislator and, ultimately, like one who had authority over the Law. Note: the listeners were well aware that this was the divine Law, given by Moses by virtue of power that God himself had granted him as his representative and mediator with the people of Israel.

The evangelists and the early Christian community who reflected on that observation of the listeners about Jesus' teaching, realised even better its full significance, because they could compare it with the whole of Christ's subsequent ministry. For the Synoptics and their readers, it was therefore logical to move from the affirmation of a power over the Mosaic Law and the entire Old Testament to that of the presence of a divine authority in Christ. And not only as in an Envoy or Legate of God as it had been in the case of Moses: Christ, by attributing to himself the power to authoritatively complete and interpret or even give in a new way the Law of God, showed his consciousness of being "equal to God" (cf. Phil 2:6).

2. That Christ's power over the Law involves divine authority is shown by the fact that he does not create another Law by abolishing the old one: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have not come to abolish but to fulfil" (Mt 5:17). It is clear that God could not "abolish" the Law that he himself gave. He can instead - as Jesus Christ does - clarify its full meaning, make its proper sense understood, correct the false interpretations and arbitrary applications, to which the people and their own teachers and leaders, yielding to the weaknesses and limitations of the human condition, have bent it.

This is why Jesus announces, proclaims and demands a "righteousness" superior to that of the scribes and Pharisees (cf. Mt 5:20), the "righteousness" that God Himself has proposed and demands with the faithful observance of the Law in order to the "kingdom of heaven". The Son of Man thus acts as a God who re-establishes what God has willed and placed once and for all.

3. For of the Law of God he first of all proclaims: "Verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass away, not one iota or one sign of the law shall pass away, and all things shall be fulfilled" (Matt 5:18). It is a drastic statement, with which Jesus wants to affirm both the substantial immutability of the Mosaic Law and the messianic fulfilment it receives in his word. It is about a "fullness" of the Old Law, which he, teaching "as one who has authority" over the Law, shows to be manifested above all in love of God and neighbour. "On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets" (Mt 22:40). It is a "fulfilment" corresponding to the "spirit" of the Law, which already transpires from the "letter" of the Old Testament, which Jesus grasps, synthesises, and proposes with the authority of one who is Lord also of the Law. The precepts of love, and also of the faith that generates hope in the messianic work, which he adds to the ancient Law, making its content explicit and developing its hidden virtues, are also a fulfilment.

His life is a model of this fulfilment, so that Jesus can say to his disciples not only and not so much: Follow my Law, but: Follow me, imitate me, walk in the light that comes from me.

4. The Sermon on the Mount, as recorded by Matthew, is the place in the New Testament where one sees Jesus clearly affirmed and decisively exercised the power over the Law that Israel received from God as the cornerstone of the covenant. It is there that, after having declared the perennial value of the Law and the duty to observe it (Mt 5:18-19), Jesus goes on to affirm the need for a "justice" superior to "that of the scribes and Pharisees", that is, an observance of the Law animated by the new evangelical spirit of charity and sincerity.

The concrete examples are well known. The first consists in the victory over wrath, resentment, and malice that easily lurk in the human heart, even when one can exhibit an outward observance of the Mosaic precepts, including the one not to kill: "You have heard that it was said to the ancients, 'You shall not kill; whoever kills shall be brought into judgment. But I say to you, whoever is angry with his brother shall be brought into judgment" (Mt 5:21-22). The same thing applies to anyone who offends another with insulting words, with jokes and mockery. It is the condemnation of every yielding to the instinct of aversion, which potentially is already an act of injury and even of killing, at least spiritually, because it violates the economy of love in human relations and hurts others, and to this condemnation Jesus intends to counterpose the Law of charity that purifies and reorders man down to the innermost feelings and movements of his spirit. Jesus makes fidelity to this Law an indispensable condition of religious practice itself: "If therefore you present your offering at the altar and there you remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar, and go first to be reconciled with your brother and then return to offer your gift" (Mt 5:23-24). Since it is a law of love, it is even irrelevant who it is that has something against the other in his heart: the love preached by Jesus equals and unifies all in wanting good, in establishing or restoring harmony in relations with one's neighbour, even in cases of disputes and legal proceedings (cf. Mt 5:25).

5. Another example of perfecting the Law is that of the sixth commandment of the Decalogue, in which Moses forbade adultery. In hyperbolic and even paradoxical language, designed to draw the attention and shake the mood of his listeners, Jesus announces. "You have heard that it was said, Do not commit adultery, but I say to you . . ." (Mt 5:27); and he also condemns impure looks and desires, while recommending the flight from opportunities, the courage of mortification, the subordination of all acts and behaviour to the demands of the salvation of the soul and of the whole man (cf. Mt 5:29-30).

This case is related in a certain way to another one that Jesus immediately addresses: "It was also said: Whoever repudiates his wife, let him give her the act of repudiation; but I say to you . . ." and declares forfeited the concession made by the ancient Law to the people of Israel "because of the hardness of their hearts" (cf. Mt 19:8), prohibiting also this form of violation of the law of love in harmony with the re-establishment of the indissolubility of marriage (cf. Mt 19:9).

6. With the same procedure, Jesus contrasts the ancient prohibition of perjury with that of not swearing at all (Mt 5, 33-38), and the reason that emerges quite clearly is still founded in love: one must not be incredulous or distrustful of one's neighbour, when he is habitually frank and loyal, and rather one must on the one hand and on the other follow this fundamental law of speech and action: "Let your language be yes, if it is yes; no, if it is no. The more is from the evil one" (Mt 5:37).

7. And again: "You have heard that it was said, 'An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth; but I say to you, do not oppose the evil one...'" (Mt 5:38-39), and in metaphorical language Jesus teaches to turn the other cheek, to surrender not only one's tunic but also one's cloak, not to respond violently to the anguish of others, and above all: "Give to those who ask you and to those who seek a loan from you do not turn your back" (Mt 5:42). Radical exclusion of the law of retribution in the personal life of the disciple of Jesus, whatever the duty of society to defend its members from wrongdoers and to punish those guilty of violating the rights of citizens and the state itself.

8. And here is the ultimate refinement, in which all the others find their dynamic centre: "You have heard that it was said, 'You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy; but I say to you, love your enemies and pray for your persecutors, that you may be children of your heavenly Father, who makes his sun rise on the wicked and on the good, and makes it rain on the just and on the unjust . . ." (Mt 5:43-45). To the vulgar interpretation of the ancient Law that identified the neighbour with the Israelite and indeed with the pious Israelite, Jesus opposes the authentic interpretation of God's commandment and adds to it the religious dimension of the reference to the clement and merciful heavenly Father, who benefits all and is therefore the supreme exemplar of universal love.

Indeed, Jesus concludes: "Be... perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect" (Mt 5:48). He demands of his followers the perfection of love. The new law he brings has its synthesis in love. This love will make man overcome the classic friend-enemy opposition in his relations with others, and will tend from within hearts to translate into corresponding forms of social and political solidarity, even institutionalised. The irradiation of the 'new commandment' of Jesus will therefore be very broad in history.

9. At this point, we would particularly like to note that in the important passages of the "Sermon on the Mount", the contrast is repeated: "You have heard that it was said . . . But I say to you"; and this is not to "abolish" the divine Law of the old covenant, but to indicate its "perfect fulfilment", according to the meaning intended by God the Lawgiver, which Jesus illuminates with a new light and explains in all its fulfilling value of new life and generator of new history: and he does so by attributing to himself an authority that is that of God the Lawgiver. It can be said that in that expression repeated six times: I say to you, there resounds the echo of that self-definition of God, which Jesus also attributed to himself: "I am" (cf. Jn 8:58).

10. Finally, one must recall the answer that Jesus gave to the Pharisees, who reproached his disciples for plucking the ears of grain from the fields full of wheat in order to eat them on the Sabbath, thus violating the Mosaic law. Jesus first cites to them the example of David and his companions who did not hesitate to eat the "offering loaves" to feed themselves, and that of the priests who on the Sabbath day did not observe the law of rest because they performed their duties in the temple. Then he concludes with two peremptory statements, unheard of for the Pharisees: "Now I say to you that there is something greater here than the temple . . .", and: "The Son of Man is Lord even of the Sabbath" (Mt 12:6.8; cf. Mk 2:27-28). These are statements that clearly reveal the consciousness Jesus had of his divine authority. Calling himself "one above the temple" was a quite clear allusion to his divine transcendence. Then proclaiming himself "lord of the Sabbath", i.e. of a Law given by God himself to Israel, was an open proclamation of his authority as the head of the messianic kingdom and promulgator of the new Law. It was therefore not a matter of mere derogations from the Mosaic Law, admitted even by the rabbis in very restricted cases, but of a reintegration, a completion and a renewal that Jesus enunciates as eternal: "Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away" (Mt 24:35). What comes from God is eternal, as God is eternal.

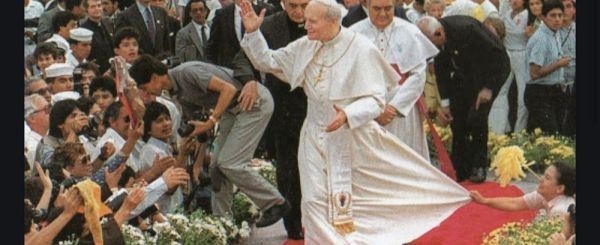

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 14 October 1987]