XXX Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C) [26 October 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. Another lesson on prayer from Jesus in the Gospel, and what a lesson!

First Reading from the Book of Sirach (35:15b-17, 20-22a)

'God does not judge by appearances' (Sir 35) The book of Sirach, written by Ben Sira around 180 BC in Jerusalem, was born in a time of peace and cultural openness under Greek rule. However, this apparent serenity hides a risk: contact between Jewish and Greek culture threatens the purity of the faith, and Ben Sira intends to transmit the religious heritage of Israel in its integrity. The Jewish faith, in fact, is not a theory, but an experience of covenant with the living God, discovered progressively through his works. God is not a human idea, but a surprising revelation, because 'God is God and not a man' (Hos 11:9). The central text affirms that God does not judge according to appearances: while men look at the outside, God looks at the heart. He hears the prayer of the poor, the oppressed, the orphan and the widow, and – in a wonderful image – 'the widow's tears run down God's cheeks', a sign of his mercy that vibrates with compassion. Ben Sira teaches that true prayer arises from precariousness: when man discovers himself to be poor and without support, his heart truly opens to God. Precarity and prayer are of the same family: only those who recognise their weakness pray sincerely. Finally, the sage warns that it is not outward sacrifices that please God, but a pure heart disposed to do good: What pleases the Lord above all is that we keep away from evil. The Lord is a just judge, who does not show partiality, but looks at the truth of the heart. In summary, Ben Sira reminds us that God does not judge by appearances but by the heart, that authentic prayer arises from poverty, and that divine mercy is manifested in his compassionate closeness to the little ones and the humble.

Responsorial Psalm (33/34:2-3, 16, 18, 19, 23)

Here is another alphabetical psalm, i.e., each verse follows the order of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. This indicates that true wisdom consists in trusting in God in everything, from A to Z. The text echoes the first reading from Sirach, which encouraged the Jews of the second century to maintain the purity of their faith in the face of the seductions of Greek culture. The central theme is the discovery of a God who is close to human beings, especially those who suffer: "The Lord is close to the brokenhearted." This is one of the greatest revelations of the Bible: God is not a distant or jealous being, but a Father who loves and shares in human suffering. Ben Sira poetically said that "our tears flow down God's cheeks": an image of his tender and compassionate mercy. This revelation is rooted in the journey of Israel. In the time of Moses, pagan peoples imagined rival and envious gods. Genesis corrects this view, showing that suspicion of God is a poison, symbolised by the serpent. Through the prophets, Israel gradually came to understand that God is a Father who accompanies, liberates and consoles, the 'God-with-us' (Emmanuel). The burning bush (Ex 3) is the foundation of this faith: 'I have seen the misery of my people, I have heard their cry, I know their sufferings'. Here God reveals himself as the One who sees, listens and acts. He does not remain a spectator, but inspires Moses and his children with the strength to liberate, transforming suffering into hope and commitment. The psalm reflects this experience: after undergoing trials, the people proclaim their praise: "I will bless the Lord at all times" because they have experienced a God who listens, liberates, watches over, saves and redeems. The name "YHWH," the "Lord," indicates precisely the constant presence of God alongside his people. Finally, the text teaches that in times of trial it is not only permissible but necessary to cry out to God: He is attentive to our cry and responds, not always by eliminating suffering, but by making himself present, reawakening trust, and giving us the strength to face evil. In summary, the psalm and the reflection that accompanies it give us three certainties: God is close to those who suffer and hears the cry of the poor. His presence does not take away the pain, but illuminates it and transforms it into hope. True faith comes from trust in this God who sees, hears, frees and accompanies man at all times.

Second Reading from the Second Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to Timothy (4:6-8, 16-18)

"The good fight" (2 Tim 4:6-18). The text presents St Paul's last spiritual testament, written while he was in prison in Rome, aware that he would soon be executed. The letters to Timothy, although perhaps composed or completed by a disciple, contain his authentic words of farewell, imbued with faith and serenity. Paul describes his imminent death with the Greek verb analuein, which means 'to untie the ropes', 'to weigh anchor', 'to dismantle the tent': images that evoke the departure for a new journey, the one towards eternity. Looking back, the apostle takes stock of his life using the sporting metaphor of running and fighting: "I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith." Like an athlete who never gives up, Paul has reached the finish line and knows that he will receive the "crown of righteousness," the reward promised to all the faithful. He does not boast about himself, because this crown is not a personal privilege, but a gift offered to all those who have lovingly desired the manifestation of Christ. The 'just judge', God, does not look at appearances but at the heart — as Sirach taught — and will give glory not only to Paul, but to all those who live in the hope of the Lord's coming. The apostle's life was a constant race towards the glorious manifestation of Christ, the horizon of his faith and his service. He recognises that the strength to persevere does not come from him, but from God himself: 'The Lord gave me strength, so that I might fulfil the proclamation of the gospel and all nations might hear it'. This divine strength sustained his mission, enabling him to proclaim Christ until the end. Paul explains that Christian life is not a competition, but a shared race, in which each person is called to run at their own pace, with the same ardent desire for the coming of Christ. In his letter to Titus, he defined Christians as those who “wait for the blessed hope and the appearing of the glory of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ” — words that the liturgy repeats every day at Mass. In his hour of trial, Paul also confesses the loneliness of the apostle: The first time I made my defence, no one came to my support, but all deserted me. May it not be held against them (v. 16) . Like Jesus on the cross and Stephen at the moment of his stoning, he forgives and transforms abandonment into an experience of intimate communion with the Lord, who becomes his only strength and consolation. Paul is the poor man of whom Ben Sira speaks, the one whom God listens to and consoles, the one whose tears flow down God's cheeks. His final words reveal the hope that overcomes death: "So I was delivered from the lion's mouth. The Lord will deliver me from all evil and bring me safely into heaven, and save me in his kingdom" (vv. 17-18). He does not speak of physical deliverance - he knows that death is imminent - but of spiritual deliverance from the greatest danger: losing faith, ceasing to fight. The Lord has kept him faithful and given him perseverance until the end. For Paul, death is not defeat, but a passage to glory. It is the birth into true life, the entrance into the Kingdom where he will sing forever: 'To him be glory for ever and ever. Amen.'

In summary: The text presents Paul as a model of the believer who is faithful to the end. He experiences death as a departure towards God, not as an end. He looks at life as a race sustained by grace. He recognises that strength and perseverance come from the Lord. He understands that the reward is promised to all who desire the coming of Christ. He forgives those who abandon him and finds God's presence in solitude and weakness. He sees death as a passage into the glory of the Kingdom. Paul's "good fight" thus becomes the struggle of every Christian: to remain faithful in trials, to the point of running the last stretch with our gaze fixed on Christ, the source of strength, peace and hope.

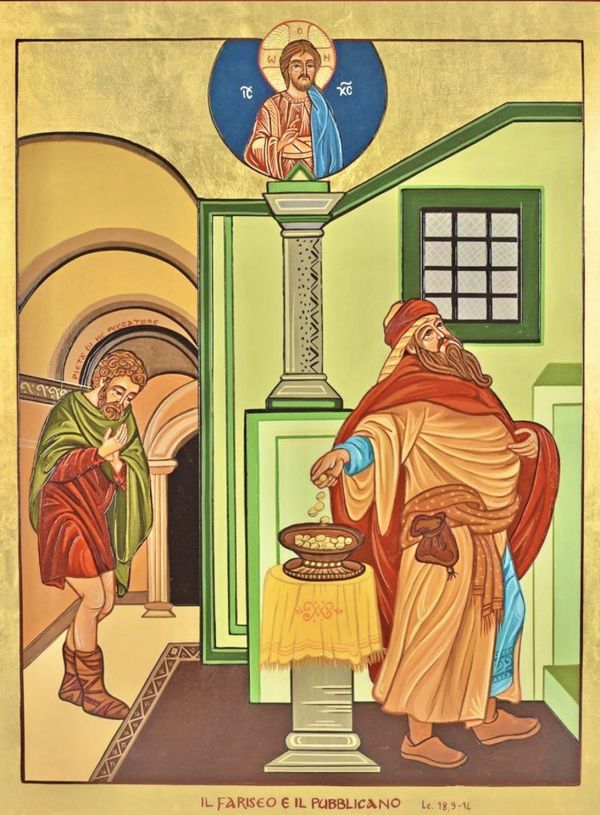

*From the Gospel according to Luke (18:9-14)

A small preliminary observation before entering into the text: Luke clearly tells us that this is a parable... so we must not imagine that all the Pharisees or all the tax collectors of Jesus' time were like those described here. No Pharisee or tax collector perfectly matched this portrait: Jesus actually presents us with two very typical and simplified inner attitudes to highlight the moral of the story. He wants us to reflect on our own attitude, because we will probably recognise ourselves now in one, now in the other, depending on the day. Let us move on to the parable: last Sunday, Luke already offered us a teaching on prayer; the parable of the widow and the unjust judge taught us to pray without ever becoming discouraged. Today, however, it is a tax collector who is offered as an example. What relationship, one might ask, can there be between a poor widow and a rich tax collector? It is certainly not the bank account that is at issue, but the disposition of the heart. The widow is poor and forced to humble herself before a judge who ignores her; the tax collector, perhaps wealthy, bears the burden of a bad reputation, which is another form of poverty. Tax collectors were unpopular, and often not without reason: they lived in a period of Roman occupation and worked in the service of the occupiers. They were considered 'collaborators'. In addition, they dealt with a sensitive issue in every age: taxes. Rome set the amount due, and the tax collectors advanced it, then received full powers to recover it from their fellow citizens... often with a large profit margin. When Zacchaeus promises Jesus to repay four times as much to those he has defrauded, the suspicion is confirmed. Therefore, when the tax collector in the parable does not dare to raise his eyes to heaven and beats his breast saying, 'O God, have mercy on me, a sinner', perhaps he is only telling the plain truth. Being true before God, recognising one's own fragility: this is true prayer. It is this sincerity that makes him 'righteous' on his return home, says Jesus. The Pharisees, on the other hand, enjoyed an excellent reputation: their scrupulous fidelity to the Law, fasting twice a week (more than the Law required!), regular almsgiving, all expressed their desire to please God. And everything the Pharisee says in his prayer is true: he invents nothing. But, in reality, he does not pray. He contemplates himself. He looks at himself with complacency: he needs nothing, asks for nothing. He takes stock of his merits — and he has many! — but God does not think in terms of merit: his love is free, and all he asks is that we trust him. Let us imagine a journalist at the exit of the Temple interviewing the two men: Sir, what did you expect from God when you entered the Temple? Yes, I expected something. And did you receive it? Yes, and even more. And you, Mr Pharisee? No, I received nothing... A moment of silence, then he adds: But I didn't expect anything, after all. The concluding sentence of the parable sums it all up: "Whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted." Jesus does not want to present God as a moral accountant who distributes rewards and punishments. He states a profound truth: those who exalt themselves, that is, those who believe themselves to be greater than they are, like the Pharisee, close their hearts and look down on others. But those who believe themselves to be superior lose the richness of others and isolate themselves from God, who never forces the door of the heart. We remain as we were, with our human 'righteousness', so different from the divine. On the contrary, those who humble themselves, who recognise themselves as small and poor, see superiority in others and can draw on their wealth. As St Paul says: 'Consider others superior to yourselves.' And this is true: every person we meet has something we do not have. This perspective opens the heart and allows God to fill us with his gift. It is not a question of an inferiority complex, but of the truth of the heart. It is precisely when we recognise that we are not 'brilliant' that the great adventure with God can begin. Ultimately, this parable is a magnificent illustration of the first beatitude: 'Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven'.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole