XXVIII Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C) [12 October 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin Mary protect us! Reflecting on the gratitude that is easier to see in those who are far away is an invitation to review our personal relationship with God.

First Reading from the Second Book of Kings (5:14-17)

This Sunday's reading begins at the moment when General Naaman, apparently as docile as a lamb, immerses himself in the waters of the Jordan, on the orders of the prophet Elisha; but we are missing the beginning of the story: let me tell it to you. Naaman is a Syrian general highly esteemed by the king of Aram (present-day Damascus). Obviously, for the people of Israel, he is a foreigner and at times even an enemy, and above all, being a pagan, he does not belong to the chosen people. Even more serious: he is a leper, which means that soon everyone will avoid him, and for him it is a real curse. Fortunately for him, his wife has an Israelite slave girl who tells her mistress, 'There is a great prophet in Samaria who could surely heal Naaman'. The mistress tells her husband Naaman, who tells the king of Aram: the prophet of Samaria can heal me. And since Naaman is in great favour, the king writes a letter of introduction to the king of Samaria recommending Naaman, who is afflicted with leprosy, to go to the prophet Elisha. The king of Israel does not know that the prophet Elisha can heal him; on the contrary, he is in a panic because he thinks that the king of Syria is looking for a pretext to wage war on him. Elisha hears about this and asks Naaman to come. Naaman arrives with his entire entourage and luggage full of gifts for the healer. In reality, only a servant opens the door slightly and simply tells him that his master orders him to immerse himself seven times in the Jordan to be purified. Naaman finds this offensive and wonders what is the point of immersing himself in the Jordan when there are rivers in Syria that are much more beautiful than the Jordan. Enraged, he sets off again for Damascus, but fortunately his servants say to him: 'Did you expect the prophet to ask you to do extraordinary things to heal you, and you would have done them? Now he is asking you to do something ordinary, so why can't you do it? Naaman allows himself to be persuaded, and this is where today's reading begins. Naaman obeys a simple order by immersing himself seven times in the Jordan and is healed. It seems simple to us, but for a great general of a foreign army, this obedience is not simple at all! The rest of the text demonstrates this. Naaman is healed and returns to Elisha to tell him two things. The first: 'Now I know that there is no God in all the earth except in Israel', and he adds that when he returns to his country, he will offer sacrifices to him. The author of this passage takes the opportunity to say to the Jews: you have had the protection of the one God for centuries, and now you see that God is also for foreigners, while you continue to be tempted by idolatry. This foreigner, on the other hand, quickly understood where his healing came from. Naaman also tells Elisha that he wants to give him a gift to thank him, but the prophet refuses emphatically: God's gifts cannot be bought. Finally, why does Naaman want to take some soil from Israel with him? He explains that he does not want to offer burnt offerings and sacrifices to other gods, but only to the God of Israel. This shows that, at the time of the prophet Elisha, all the peoples neighbouring Israel believed that the gods reigned over specific territories and, in order to offer sacrifices to the God of Israel, Naaman believed he had to take with him some soil from the land over which this God reigned.

Responsorial Psalm (97/98, 1-4)

In the first reading, Naaman, a Syrian general and therefore a pagan, is healed by the prophet Elisha and, thanks to this, discovers the God of Israel. Naaman is therefore perfectly suited to sing this psalm, which speaks of God's love both for the pagans, whom the Bible calls the nations (or peoples), and for Israel. 'The Lord has made known his salvation, he has revealed his justice in the sight of the nations' (v. 2) and immediately afterwards (v. 3): 'He has remembered his love, his faithfulness to the house of Israel', which is the consecrated expression to remember the election of Israel, the completely privileged relationship that binds this small people to the God of the universe. The simple words "his faithfulness" and "his love" are a reference to the Covenant: it is through these words that, in the desert, God made himself known to the people he chose. The phrase "God of love and faithfulness" indicates that Israel is the chosen people, but the previous phrase reminds us that if Israel has been chosen, it is not to enjoy the privilege selfishly, not to consider itself the only child, but to behave as an older brother, and its role is to proclaim God's love for all people, so as to gradually integrate all humanity into the Covenant. In this psalm, this certainty even marks the composition of the text; if you look more closely, you will notice the inclusion of verses 2 and 3. I would remind you that inclusion is a literary device often found in the Bible. It is a bit like a box in a newspaper or magazine; obviously, the purpose is to highlight the text written inside the box. In the Bible, it works the same way: the central text is highlighted, framed by two identical phrases, one before and one after. Here, the central phrase speaks of Israel, the chosen people, and is framed by two phrases that speak of the nations: the first phrase, 'The Lord has made known his salvation, he has revealed his righteousness in the sight of the nations', and the second concerns Israel: "He has remembered his love, his faithfulness to the house of Israel" and the third: "All the ends of the earth have seen the victory of our God". Here the term "the nations" does not appear but is replaced by the expression "all the ends of the earth". This means that the election of Israel is central, but we must not forget that it must radiate to all humanity. A second emphasis of this psalm is the very marked proclamation of God's kingship. For example, in the Temple of Jerusalem they sing: "Acclaim the Lord, all the earth, acclaim your king." This psalm is a cry of victory, the cry that rises on the battlefield after triumph, the teru'ah in honour of the victor. The victory of God, referred to here, is twofold: first, it is the victory of liberation from Egypt, and second, it is the victory expected at the end of time, God's definitive victory over all the forces of evil. Even then, God was acclaimed as the new king was once acclaimed on the day of his coronation, with cries of victory to the sound of trumpets, horns and the applause of the crowd. But while with the kings of the earth there was always disappointment, this time we know that we will not be disappointed; that is why this time the teru'ah must be particularly vibrant! Christians acclaim God with even greater force, because they have seen the king of the world with their own eyes: since the Incarnation of the Son, they know and affirm, against all apparent evidence to the contrary, that the Kingdom of God, that is, of love, has already begun.

Second Reading from the Second Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to Timothy (2:8-13)

The hymn "Remember Jesus Christ, risen from the dead; he is our salvation, our eternal glory" is found in its original context in the Second Letter to Timothy, where Paul writes: "Remember Jesus Christ, descendant of David". In the Jewish milieu, it was essential to affirm that Jesus was truly of the lineage of David in order to be recognised as the Messiah. Paul adds: 'He was raised from the dead: this is my Gospel'. The question is radical: either Jesus rose from the dead, or he did not. Paul, initially convinced that it was an invention, had tried to prevent the spread of this proclamation. But after his experience on the road to Damascus, he saw the Risen One and became his witness. Jesus is the conqueror of death and evil, and with him a new world is born, in which believers must participate with their whole lives. For this reason, Paul consecrates himself to proclaiming the Gospel and invites Timothy to do the same, preparing him for opposition and encouraging him to fight the good fight with courage, gentleness and trust in the Spirit he has received. The resurrection is the heart of the Christian faith. While for many Jews the resurrection of the flesh was credible, for the Greeks it was difficult to accept, as shown by the failure of Paul's preaching in Athens. Precisely because of his proclamation of the resurrection, Paul was imprisoned several times: "Christ has been raised from the dead; this is my Gospel. For his sake I suffer, even to the point of being chained like a criminal." Timothy, too, Paul warns, will have to suffer for the Gospel. Paul's chains do not stop the truth: 'I am in chains, but the Word of God is not in chains'. Jesus himself had said that if they remain silent, the stones will cry out, because nothing can stop the truth. Paul adds that he endures everything for the elect, so that they too may obtain the salvation that is in Christ Jesus, with eternal glory. Here the opening hymn echoes and probably follows an ancient baptismal hymn introduced with the formula: "Here is a word worthy of faith: If we died with him, we will live with him; if we persevere, we will reign with him." It is the mystery of Baptism, already explained in Romans 6: with it we are immersed in the death and resurrection of Christ, united with him in an inseparable way. Passion, death and resurrection constitute a single event that inaugurated a new era for humanity. The last sentences highlight the tension between human freedom and God's faithfulness because if we deny him, he too will deny us: God respects our conscious rejection. If we lack faith, he remains faithful, because he cannot deny himself, since God always remains faithful even in the face of our frailty.

From the Gospel according to Luke (17:11-19)

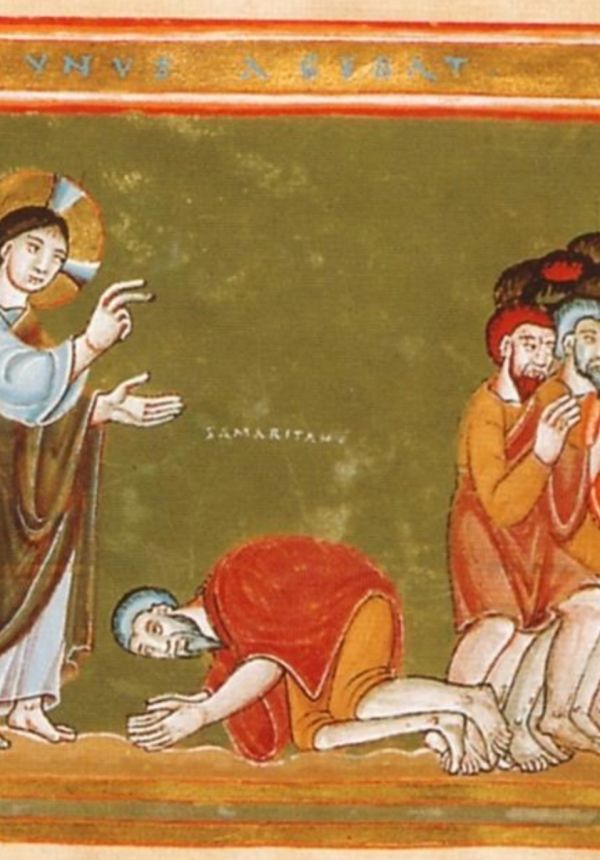

Jesus is on his way to Jerusalem, where his passion, death and resurrection await him. Luke emphasises the itinerary because what he narrates is linked to the mystery of salvation. During the journey, he meets ten lepers who, forced to remain at a distance according to the Law, cry out to him, calling him 'Master': this is a sign both of their weakness and of the trust they place in him. Unlike another episode (Lk 5:12), this time Jesus does not touch them, but only orders them to go and present themselves to the priests, a necessary step for official recognition of their healing. The order is already a promise of salvation. The story recalls the episode of Naaman and the prophet Elisha (2 Kings 5) in the first reading because as the ten set out on their journey, their leprosy disappears: their trust saves them. The disease had united them, but the healing reveals the difference in their hearts: nine Jews go to the priests, only one, a Samaritan, considered a heretic, returns. He recognises that life and healing come from God, glorifies God aloud, prostrates himself at Jesus' feet and gives him thanks: an attitude reserved for God. Thus he recognises the Messiah and understands that the true place to give glory to God is no longer the Temple in Jerusalem, but Jesus himself. His return is conversion, and Jesus proclaims it: "Get up and go; your faith has saved you." Jesus asks the other nine to account for themselves: they met the Messiah but did not recognise him, choosing to run immediately to the Temple to fulfil the Law without stopping to give thanks. The Gospel thus emphasises a recurring theme: salvation is for everyone, but often it is not those closest to God who welcome it: "He came among his own, and his own did not recognise him." Already the Old Testament affirmed the universality of salvation (cf. Ps 97/98). The first reading recalls the conversion of Naaman, a foreigner, and Jesus had rebuked Nazareth, citing the example of the Syrian who was healed while many lepers in Israel were not (Lk 4:27), arousing the anger of the synagogue. In Acts, Luke will again show the contrast between the rejection of part of Israel and the acceptance of the pagans. This question was alive in the early Christian communities: did one have to be Jewish to receive baptism, or could pagans also be accepted? The story of the converted Samaritan recalls three truths: the salvation brought by Christ through his passion, death and resurrection is for everyone; thanksgiving is often best performed by foreigners or heretics; the poor are the most open to encountering God. In conclusion, on the road to Jerusalem, that is, to salvation, Jesus leads all men who are willing to convert, whatever their origin or religion.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole