God bless us and may the Virgin protect us!

3rd Sunday in Lent (year C) [23 March 2025]

*First Reading from the book of Exodus (3:1-8a.10.13-15)

This text has a fundamental importance for the faith of Israel and also for us because for the first time mankind discovers that it is loved by God, a God who sees, hears and knows our sufferings. Never could man have come so far if God Himself had not decided to reveal Himself, and it is precisely from His autonomous revelation that Israel's faith, and consequently ours, was born. We must grasp the strength of this biblical text, which unfortunately the liturgical translation renders weakly. When we read: "I have seen the misery of my people", the Hebrew text is much more insistent, so it would be more correct to translate it this way, hearing the voice God: "indeed I have seen, yes, I have seen" the misery of my people in Egypt. A real misery as seen in the story of the Hebrew people who emigrated centuries earlier due to a famine, and while things were going well at first, then as their numbers grew, just as Moses was born the Egyptians began to worry. They kept the Hebrews as cheap labour, but wanted to prevent their population growth by having every male infant killed by the midwives. Moses was saved because he was adopted by Pharaoh's daughter and grew up in his court, but could not forget his origins, constantly torn between his adoptive family and his blood brothers, who were reduced to helplessness and revolt. Until one day he killed an Egyptian who was using violence towards a Jew, but the next day, intervening between two quarrelling Jews, they told him not to interfere, which meant that they did not recognise his responsibility for leading a rebellion against the Pharaoh while Pharaoh had decided to punish him for the murder of the Egyptian. Moses was forced, in order to avoid revenge, to flee to the Sinai desert, where he took as his wife a Midianite, Sipporah, daughter of Jethro, and today's text starts from here. While shepherding his father-in-law's flock, one day he arrived across the desert at the mountain of God, Horeb, where he met God who entrusted him with a great mission. Beware! Moses felt the misery of his brothers and had risked his life for them by killing an Egyptian, but he had to recognise his powerlessness, so he fled, marginalised by his blood brothers who recognised no authority in him. He is therefore a humanly bankrupt man who approaches a strange burning bush and from here his story changes completely. I close with two reflections. The first: Moses encounters the transcendent God and at the same time the near God. Transcendent because one can only approach him with fear and respect, but also the near God, who sees the misery of his people and raises up a deliverer. We grasp God's holiness and man's deep respect for his presence in these expressions: 'the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire from the midst of a bush'. To indicate God's presence, the periphrasis: "the Angel of the Lord" is used, which is a respectful way of speaking of God, as are the words: "Come no closer! Take off your sandals from your feet, for the place on which you stand is holy ground"; and finally "Moses then covered his face, because he was afraid to look towards God". God, however, is revealed as the God who is close to man, the one who stoops to his suffering. The second reflection concerns the way God intervenes: he sees man's suffering, acts and sends Moses. God calls a co-worker, but for the deliverance to take place, the one who is called must accept to respond, and the one who suffers must accept to be saved.

*Responsorial Psalm (102 (103), 1-2, 3-4, 6-7, 8.11)

In the first reading, the account of the burning bush from the book of Exodus chapter 3, God reveals his Name: 'I am' ... that is, 'with you' in the depths of your suffering. Almost echoing this, the responsorial psalm proclaims: 'Merciful and gracious is the Lord, slow to anger and great in love'. The two formulations of the Mystery of God: 'I am' and 'Merciful and gracious' complement each other. In the episode of the burning bush, the expression 'I am' or 'I am who I am' should not be taken as the definition of a philosophical concept. The repetition of the verb 'I am' is an idiomatic form of the Hebrew language that serves to express intensity, and God begins by recalling the long history of the Covenant with the Fathers: 'I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob' to express his faithfulness to his people through the ages. Then he wanted to manifest his compassion for humiliated Israel, enslaved in Egypt, and only then does he reveal his Name 'I am'. Moses' first discovery at Sinai was precisely the intense presence of God in the heart of human despair: 'I have seen,' said God, 'yes, I have seen the misery of my people in Egypt, and I have heard their cries under the beatings of the overseers. Yes, I know his sufferings. I have come down to deliver them..." Moses retained such a profound memory that he drew from it the incredible energy that transformed him from a lonely man, exiled and rejected by all, into the tireless leader and liberator of his people. However, when Israel remembers this unprecedented adventure, it knows very well that its first liberator is God, while Moses is only its instrument. Moses' 'Here I am' (like that of Abraham, and of so many others later) is the answer that allows God to bring about the liberation of humanity. And, henceforth, when one says "The Lord" - translation of the four letters (YHVH) of God's name - one evokes God's liberating presence. To better understand the mystery of God's presence, we need to go back to the account of the burning bush: the bush burned with fire, but was not consumed (cf. Ex 3:2). God reveals himself in two ways: through this vision as through the word that proclaims his Name. Confronted with the flame that burns a bush without consuming it, Moses is invited to understand that God, comparable to a fire, is in the midst of his people (the bush) as a presence that does not consume or destroy the people; Moses veiled his face and understood that one should not be afraid. Thus came the vocation of Israel, the place chosen by the Lord to manifest his presence and, from then on, the chosen people will testify that God is among men and there is nothing to fear. The responsorial psalm proclaims this: "Merciful and gracious is the Lord", that is, tenderness and mercy, echoing another revelation of God to Moses (Ex 34:6), and the two merge into a single truth. The psalm continues: 'The Lord does just things, he defends the rights of all the oppressed. He made known to Moses his ways, his works to the children of Israel". God is the same from everlasting to everlasting: he is in our midst, a flame, a fire of tenderness and mercy, and Israel is called to bear witness to this in the world that needs such a message because it suffers if such a fire does not burn there. Hence the preaching of the prophets who always highlight two aspects of Israel's vocation: to proclaim one's faith by revealing the truth of which one is the bearer, and to act in the image of one's Lord, that is, working in justice in defence of the oppressed. All the prophets struggled against idolatry because a people who have experienced the presence of the God who sees their suffering cannot put their trust in idols of wood or stone and at the same time must defend the rights of the oppressed, as Isaiah says: "The fasting that pleases me...is to share your bread with the hungry, to take in the homeless poor, to clothe the naked, not to turn your back on your fellow man" (Is 58:6-7).

*Second reading from the First Letter of St Paul to the Corinthians (10:1-6.10-12)

In order to warn the community of Corinth, as it is important what he is about to say, Paul starts like this: "I do not want you to be ignorant, brothers", he then recalls what happened during the exit from Egypt and ends with "therefore, whoever thinks he is standing, watch that he does not fall", i.e. do not overestimate yourselves as no one is safe from temptation. In the first chapters of the letter, the Apostle warned the Christians of Corinth of the many risks of corruption and immorality, inviting them to be humble. He proposed to them a rereading of the entire history of the people of Israel during the Exodus: a history where God's gifts were not lacking, but man's fickleness always emerges. God promised Moses to be the faithful God, present to his people on the difficult journey towards freedom, through the Sinai desert, but in return on many occasions the people betrayed their Covenant. The Apostle retraces the stages narrated in the book of Exodus, from the departure from Egypt before the crossing of the Red Sea, when the Lord himself had taken over the leadership of operations by marching at their head by day in a pillar of cloud, to show them the way, and by night with a pillar of fire (cf. Ex 13:21-22). From the first encampment, however, the people seeing the Egyptians behind them were afraid and rebelled against Moses: "Perhaps because there were no graves in Egypt, you led us to die in the desert? What have you done to us, bringing us out of Egypt? ... Leave us alone, we want to serve the Egyptians. It is better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the desert!" (cf. Ex 14:10-11). And this will be repeated with every difficulty because the path to freedom is full of obstacles and the temptation to fall back into the old slavery is constant. Paul conveys this message to the Corinthians: Christ has set you free, but you are often tempted to fall back into the old errors and you do not realise that these behaviours make you slaves. The path of Christ seems difficult to you, but trust him: he alone is the true deliverer. Even at the crossing of the Red Sea, in a situation that was humanly desperate, God intervened (cf. Ex 14:19) and the people were able to cross it because the waters opened up to let them pass: "The Lord all night long drove the sea with a strong east wind, making it dry; the waters parted" (Ex 14:21). The trials will continue and, on many occasions, the Israelites will return to regret the security of slavery in Egypt. They will complain and rebel instead of trusting in the knowledge that God will always intervene. The episode that best highlights this crisis is when in the desert the people began to really suffer thirst and began to protest, accusing Moses and, through him, God himself: "Why did you bring us up from Egypt? To make us and our children and our cattle die of thirst?" (Ex 17:3). It was then that Moses struck the Rock and water gushed out of it and gave that place the name Massa e Meriba, which means "Trial and Dispute", because the children of Israel had disputed the Lord (Ex 17:7). The problems of the Corinthians, of course, are not the same, but there are other "Egypts" and other forms of slavery: for these new Christians there are choices to be made in the name of their baptism, there are behaviours that can no longer be maintained. And these choices sometimes become painful. Let us think of the demands of the catechumenate that entailed real renunciations of certain behaviours, certain relationships and sometimes even a trade; renunciations that can only be accepted when one places all one's trust in Jesus Christ. In the mixed and particularly permissive society of Corinth, maintaining Christian behaviour required courage, but Paul emphasises, what seems folly to men is true wisdom in the eyes of God. It is no coincidence that, during Lent, the Church invites us to meditate on this text of Paul's, which reminds us how demanding we must be with ourselves in order not to fall into old slavery, and instead how much renewed trust must be placed in God at all times.

*From the Gospel according to St Luke (13:1-9)

In this Sunday's gospel, we find the account of two facts of crime, Jesus' commentary with the parable of the fig tree, and their juxtaposition is surprising, though certainly the evangelist intentionally proposes it to us. Therefore, it is precisely the parable that can help us understand the meaning of what Jesus means about the two news events.

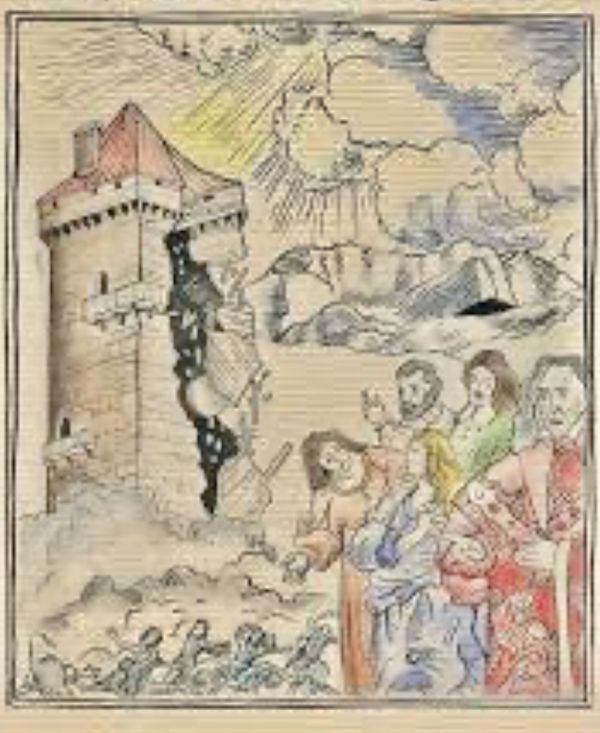

The first concerns a massacre of Galilean pilgrims who had come to Jerusalem to offer a sacrifice in the Temple. These events were not unusual at the time since Pilate's cruelty was known and pilgrims were often accused of being opponents of Roman power. In truth, the majority of the Jewish people hardly tolerated the occupation of the Romans and it was precisely from Galilee, at the time of Jesus' birth, that the revolt of Judas the Galilean had started. The second news event, the collapse of the tower of Siloe with 18 victims, was a tragedy like many others. From Jesus' words we can guess the question that the disciples had on their lips and that we often hear repeated even today: 'What did they do wrong to deserve this divine punishment? This is the great question about suffering, which to this day is an unsolved problem. In the Bible, the book of Job poses the problem in the most dramatic way and the three friends - Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar - try to explain his suffering through the principle of retributive justice, according to which suffering is a punishment for sin and therefore Job must have committed some hidden fault that justifies his afflictions. However, Job declares himself innocent and rejects these explanations. At the end of the book, God intervenes and rebukes Job's friends for speaking incorrectly about him, instead representing Job's sincerity in his search for answers. The theme of suffering is a complex one, and God, who recognises all human attempts to interpret pain as ineffective because the control of events eludes human intelligence, invites man to maintain his trust in God in every difficulty, even the most dramatic. Faced with the horror of the massacre of the Galileans and the collapse of the tower of Siloe, Jesus is categorical: there is no direct link between suffering and sin so those Galileans were no more sinners than the others, nor were the eighteen people crushed by the tower of Siloe more guilty than the other inhabitants of Jerusalem. But then, starting from these two events, he invites the disciples to true conversion, indeed he insists on the urgency of conversion, echoing the appeals of the prophets such as Amos, Isaiah and many others. This is followed by the parable of the fig tree, which softens the apparent harshness of his words because it shows that God's thoughts are very different from those of men and shows us the face of a patient and merciful God. For us, a barren fig tree that uselessly exploits the soil must be cut down, that is, someone who does evil must be punished at once and even eliminated, but not so thinks our God who, on the contrary, affirms: "As I live - oracle of the Lord God - I take no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but in his conversion, that he may live" (Ez 33:11). Jesus does not primarily ask us to change our behaviour, but to urgently change the image of a God who punishes. On the contrary, precisely in the face of evil, the Lord is "merciful and pitiful", as this Sunday's Psalm says: merciful, that is, bent over our miseries, and the conversion that awaits us is to entrust ourselves to his infinite and patient mercy. In short, taking up the conclusions of the book of Job, Jesus invites us not to try to explain suffering with sin and other theories as it is a mystery, but to keep our trust in God in spite of everything. And when he says: "unless you are converted, you will all perish in the same way" he means that humanity is heading for ruin when it loses trust in God. Like Israel in the wilderness, whose adventure Paul recalls in the second reading, we too are challenged to always choose whether to trust or to be suspicious of God. However, we must know that his plan is always in our favour and if it changes our heart (that is conversion), it will also change the face of the world.

+Giovanni D’Ercole