Today, 25 March, we are in the heart of the Jubilee contemplating the mystery of the Annunciation and Incarnation of the Word. It used to be a predominantly Marian feast, as it still appears in many popular religious traditions. With the liturgical reform, it was highlighted as an important Christological solemnity that immerses us in the heart of the Incarnation of the eternal Word: God becoming man for our salvation. The presence of Mary - The Annunciation - as the one who with her 'yes' made the mystery of our salvation possible, the miracle of the Incarnation, always remains strong; and she invites each one of us to unite our 'yes' to hers, aware that only in humility is the human heart capable of responding to God's call.

IV Sunday in Lent (year C) [30 March 2025]

*First Reading From the book of Joshua (5, 9a 10- 12)

Moses did not enter the promised land because he died on Mount Nebo, at the Dead Sea, on the side that today corresponds to the Jordanian shore. It was therefore not he who introduced the people of Israel into Palestine, but his servant and successor Joshua. The whole book of Joshua recounts the entry of the people into the promised land, starting with the crossing of the Jordan since the tribes of Israel entered Palestine from the east. The aim of the writer of this book is quite clear: if the author recalls God's work for Israel, it is to exhort the people to faithfulness. Within the few lines of today's text lies a real sermon that is divided into two teachings: firstly, we must never forget that God has delivered the people from Egypt; and secondly, if he has delivered them, it is to give them this land as he promised our fathers. We receive everything from God, but when we forget this, we put ourselves in dead-end situations. This is why the text draws continuous parallels between leaving Egypt, life in the desert and entering Canaan. For example, in chapter 3 of the book of Joshua, the crossing of the Jordan is solemnly recounted as a repetition of the Red Sea miracle. In this Sunday's text, the author insists on the Passover: "they celebrated the Passover, on the fourteenth day of the month, in the evening". Just as the celebration of the Passover had marked the exit from Egypt and the Red Sea miracle, the Passover now follows the entry into the promised land and the Jordan miracle. These are intentional parallels by which the author wants to say that, from the beginning to the end of this incredible adventure, it is the same God who acts to free his people, in view of the promised land. The book of Joshua comes immediately after Deuteronomy. "Joshua" is not his name, but the nickname given to him by Moses: at first, he was simply called "Hoshéa", "Hosea" meaning "He saves" and the new name, "Joshua" ("Yeoshoua") contains the name of God to indicate more explicitly that only God saves. Joshua after all understood that he alone cannot deliver his people. The second part of today's text is surprising because on the surface it speaks only of food, but there is much more: "On the day after the Passover, they ate the produce of that land: unleavened and toasted wheat. And from the next day, as they had eaten, the manna ceased. The Israelites had no more manna: that year they ate the fruits of the land of Canaan." This change of food suggests a weaning: a new page is turned, a new life begins and the desert period with its difficulties, recriminations and even miraculous solutions ends. Now Israel, having arrived in the God-given land, will no longer be nomads, but a sedentary people of farmers feeding on the products of the soil; an adult people responsible for its own subsistence. Having the means to provide for themselves, God does not replace them because he has great respect for their freedom. However, this people will not forget the manna and will retain the lesson: just as the Lord provided in the desert, so Israel must become solicitous towards those who for various reasons are in need. It is clearly stated in the Book of Deuteronomy: God has taught us to feed the poor by sending down bread from heaven for the children of Israel, and now it is up to us to do the same (cf. Deut.34:6). Finally, the crossing of the Jordan and the entry into the promised land, the land of freedom, helps us to better understand Jesus' baptism in the Jordan, which will become the sign of the new entry into the true land of freedom.

*Responsorial Psalm (33 (34) 2-3, 4-5, 6-7)

In this psalm, as in others, each verse is constructed in two lines in dialogue and ideally it should be sung in two alternating choruses, line by line. It is composed of 22 verses corresponding to the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, in poetry called an acrostic: each letter of the alphabet is placed vertically in front of each verse, beginning with the corresponding letter in the margin. This procedure, quite frequent in psalms, indicates that we are dealing with a psalm of thanksgiving for the covenant. We could say that it is a response to the first reading from the book of Joshua, where although it tells a story, there is actually an invitation to give thanks for all that God has accomplished for Israel. The language of thanksgiving is omnipresent, as is evident in the first verses: 'I will bless the Lord at all times ... on my lips always his praise ... magnify the Lord with me ... let us exalt his name together'. The speaker is Israel, witness to the work of God: a God who responds, frees, listens, saves: "I sought the Lord: he answered me; from all fear he delivered me... this poor man cries out and the Lord listens to him: he saves him from all his anguish." This attention of God emerges in the passage from chapter 3 of Exodus, which was the first reading of last Sunday, the third of Lent i.e. the episode of the burning bush: "I have seen the misery of my people... their cry has reached me... I know their sufferings." Israel is the poor liberated by God's mercy, as we read in this psalm, and has discovered its twofold mission: firstly, to teach all the humble about faith, understood as a dialogue between God and man who cries out his distress and God hears him, liberates him and comes to his aid; secondly, to be willing to collaborate with God's work. Just as Moses and Joshua were God's instruments to deliver his people and bring them into the promised land, so Israel will be the attentive ear to the poor and the instrument of God's concern for them: 'let the poor hear and rejoice'. Israel must echo down the centuries this cry, which is an interwoven polyphony of suffering, praise and hope to alleviate all forms of poverty. It is necessary, however, to be poor in heart with the realism of recognising ourselves as small and to invoke God for help in the certainty that he accompanies us in every circumstance to help us face life's obstacles.

*Second Reading from the Second Epistle of St Paul to the Corinthians (5:17-21)

This text can be understood in two ways and everything revolves around the central phrase: "not imputing (God) to men their faults" (v.19) which can have two meanings. The first: since the beginning of the world, God has kept count of men's sins, but, in his great mercy, he agreed to wipe them out through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ and this is what is known as 'substitution', i.e. Jesus took on in our place a debt too great for us. Secondly, God has never counted the sins of men, and Christ came into the world to show us that God has always been love and forgiveness, as we read in Psalm 102 (103): "God turns away our sins from us". The whole path of biblical revelation moves us from the first hypothesis to the second, and in order to understand it better, we need to answer these three questions: Does God keep count of our sins? Can we speak of 'substitution' in the death of Christ? If God does not reckon with us and if we cannot speak of 'substitution', how should we interpret this text of Paul?

First: Does God keep count of our sins? At the beginning of the covenant history, Israel was certainly convinced of this and it is clear why. Man cannot discover God unless God himself reveals himself to him. To Abraham God does not speak of sin, but of covenant, of promise, of blessing, of descent, and never does the word 'merit' appear. "Abraham had faith in the Lord and it was credited to him as righteousness" (Gen 15:6), so faith is the only thing that counts. God does not keep track of our actions, which does not mean that we can do anything, because we are responsible for building the Kingdom. To Moses, the Lord reveals himself as merciful and forgiving, slow to anger and rich in love (cf. Ex 34:6). David, precisely on the occasion of his sin, understands that God's forgiveness precedes even our repentance and Isaiah observes that God surprises us because His thoughts are not our thoughts: He is only forgiveness for sinners (cf. Is 55:6-8). In the Old Testament, the chosen people already knew that God is tenderness and forgiveness and called him Father long before we did. The parable of Jonah, for example, was written precisely to show that God cares even for the Ninevites, Israel's historical enemies.

Second: Can one speak of 'substitution' in the death of Christ? If God does not keep count of sins and therefore we do not have a debt to pay, there is no need for Jesus to replace us. Moreover, the New Testament texts speak of solidarity, never substitution, and Jesus does not act in our place, nor is he our representative. He is the 'firstborn' as Paul says, who opens the way and walks before us. Mixed in with sinners he asked for Baptism from John and on the cross he accepted to give his life for us. He drew near to us so that we could draw near to Him.

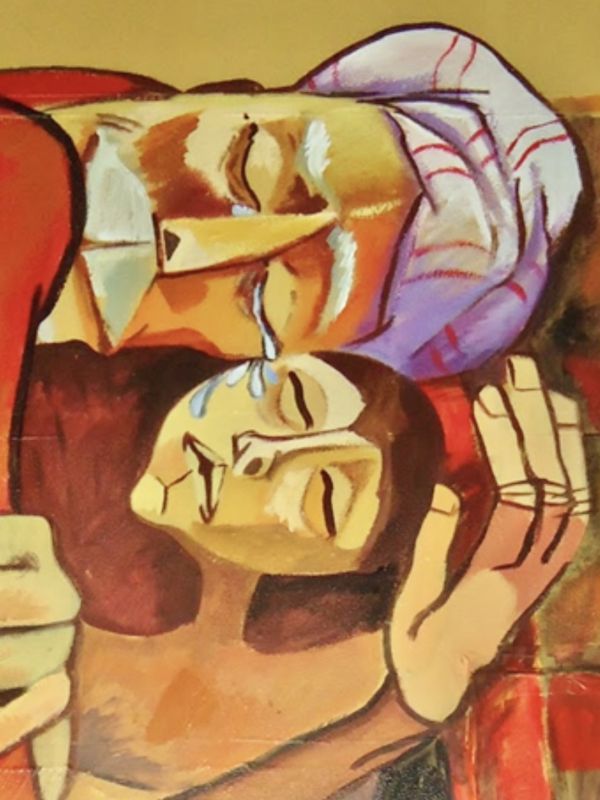

Thirdly: How then is this text of Paul's to be interpreted? First of all, God has never kept count of the sins of men, and Christ came into the world to make us understand this. When he says to Pilate: "I have come into the world to bear witness to the truth" (Jn 18:37), he affirms that his mission is to reveal the face of God who is always love and forgiveness. And when Paul writes: "...not imputing (God) to men their faults" he means to make it clear that God erases our false ideas about Him, those that portray Him as an accountant. Jesus came to show the face of God Love, but was rejected and therefore accepted to die. He had become too inconvenient for the religious authorities of the time, who thought they knew better than he did who God was, and so he died on the cross because of human pride that had turned into implacable hatred. To Philip in the Upper Room he said: "He who has seen me has seen the Father" (Jn 14:9) and even in the midst of humiliation and hatred he only uttered words of forgiveness. We understand at this point the sentence with which this passage closes: "He who knew no sin, God made him sin for our sake, that in him we might become the righteousness of God" (v. 21). On the face of Christ crucified, we contemplate to what extent the horror of our sin reaches us, but also to what extent God's forgiveness reaches us, and from this contemplation our conversion can be born: "They shall look upon him whom they have pierced", a text from the prophet Zechariah (12:10), which we find in the Fourth Gospel (Jn 19:37). Hence our vocation as ambassadors of God's love: "We beseech you in the name of Christ: be reconciled to God" (v.20).

*From the Gospel according to Luke (15:1-3. 11-32)

The interpretive key to this text is found in the very first words. St Luke writes that "all publicans and sinners came to Jesus to listen to him" while "the Pharisees and scribes murmured, saying, 'He welcomes sinners and eats with them'. The former are public sinners to be avoided, while the latter are honest people who seek to do what pleases God. In truth, the Pharisees were generally upright, pious people and faithful to the Law of Moses, shocked however by the behaviour of Jesus who does not seem to understand who he is dealing with if he even eats and mingles with sinners. God is the Holy One and for them there was a total incompatibility between God and sinners and therefore Jesus, if he was truly from God, had to avoid associating with them. This parable is intended to help one discover the true face of God who is Father. In fact, the main character in this story is God himself, the father who has two kinds of sons, both with at least one point in common, namely the way they conceive of their relationship with their father in terms of merits and accounts, even though they behave differently: the younger offends him gravely, unlike the elder, and in the end, however, acknowledges his sin: "I am no longer worthy to be called your son"; the elder, on the other hand, boasts of having always obeyed but complains that he has never even received a kid as he deserves. The Father is out of these calculations and does not want to hear about merits because he loves his children and in this relationship there is no room for calculating accounts. To the prodigal son, who had demanded 'my share of the inheritance that is due to me', he had gone far beyond the demand, as he will eventually say to both of them: all that is mine is yours. To the prodigal son who returns he does not even leave time to express any repentance, he does not demand an explanation; on the contrary, he wants to celebrate immediately, because 'this son of mine was dead and has come back to life; he was lost and has been found'. The lesson is clear: with God it is not a matter of calculations, merits, even if we struggle to eradicate this mentality, and the whole Bible, from the Old Testament onwards, shows the slow and patient pedagogy with which God seeks to make himself known as Father, ready to celebrate every time we return to him.

Two small comments to conclude:

1. In the first reading, taken from the book of Joshua, Israel is nourished by manna during the desert crossing, while here there is no manna for the son who refuses to live with his father and finds himself in an existential desert, because he has cut himself off.

2. Concerning the connection with the parable of the lost sheep, which is also found in this chapter of Luke, it is observed that the shepherd goes to look for the lost sheep and brings it back by putting it on his shoulders, while the father does not prevent the son from leaving and does not force him to return because he respects his freedom to the full.

+Giovanni D'Ercole