Brief Commentary on the Readings [10.11.24]

*First Reading 1 Kings 17:10-16

The prophet Elijah is far from his homeland, in Sarepta, a city on the Phoenician coast, which at the time was part of the kingdom of Sidon and not of the kingdom of Israel. We are in the 9th century B.C., King Ahab had married Queen Jezebel (around 870), thus not a daughter of Israel, but the daughter of the king of Sidon, in order to implement a policy of alliance, but exposing himself to the grave risk of apostasy, because Jezebel brought with her customs, prayers, statues and the priests of the cult of Baal, the god of fertility, rain, lightning and wind. King Ahab, a very weak person, thus ends up betraying his religion and even builds a temple to Baal. Elijah and the faithful Jews feel ashamed at the betrayal of their faith, knowing full well the first commandment: "You shall have no other gods but me!", which is the a. b. c. of the Jewish faith: God alone is God, all other idols are useless. Elijah opposes Jezebel and, in order to prove the falsity of the idols, as a severe drought was just then occurring in Israel, he launches a challenge: you hold Baal to be the god of rain, but I will prove that the God of Israel alone is the one true God, master of everything, of rain and drought. The unfolding of this challenge will take place, but today's text stops at this point. Warned by God, Elijah prophesies that there will be years of severe drought and, following a divine command, he takes refuge by the Kerith stream, east of the Jordan (1 Kings 17:3-4). The drought persists, the stream dries up and God orders him to go to the distant Sarepta where he meets a poor widow from whom, as a poor beggar, he asks for "a piece of bread". The woman confesses to him that she has no more bread, for all she has left is a handful of flour in a jar with a little oil in it; she gathers two pieces of wood to prepare a loaf for her and her son, they will eat it and then prepare to die. The prophet reminds her that God can do everything and invites her to prepare a 'little bread' for him and then she will share what is left with her son. He assures her that the God of Israel will intervene: the jar of flour will not run out and the jar of oil will not be emptied until the day the Lord makes it rain. And so it came to pass: "the jar of flour did not run out and the jar of oil did not empty". The story of the widow of Sarepta is similar to that of the widow who, as we read today in the gospel, in the Temple of Jerusalem gives God all her change, a clear example of a simple faith that deprives itself of everything and trusts in the word of the God of Israel. The message is clear: while Israel falls back into idolatry, a foreign, pagan widowed woman is rewarded by the Lord for her great faith. There is also a detail to point out: the widow heard God personally command her to provide for the prophet, and this shows that God's word resounds where and how He wills, even among the Gentiles. Jesus would refer to this episode when speaking to his countrymen in Nazareth (Lk 4:25-26). Indeed, in the late texts of the Old Testament (and the first book of Kings is part of it), pagans are often cited as an example to indicate that salvation is promised to all mankind, not being reserved to Israel alone. In short, God is solicitous towards those who trust in him, and the great lesson of this biblical episode is that the Lord's solicitude never betrays those who trust in him.

*Psalm 145 (146), 5-6a, 6c-7ab, 8bc-9a, 9b-10

With this psalm, Israel sings its history, giving thanks to God for his constant protection. "Oppressed, afflicted, hungry", the people had experienced oppression in Egypt from which they were delivered "with a strong hand and an outstretched arm" as they would later be from deportation to Babylon, and this psalm was written on their return from exile from Babylon, perhaps for the dedication of the Temple restored after its destruction in 587 BC by the troops of the king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar. Indeed, fifty years later (in 538 BC), Cyrus, king of Persia, defeated Babylon, authorised the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple, the dedication of which was celebrated with joy and fervour as we read in the book of Ezra: "The sons of Israel, the priests, the Levites and the rest of the deported did joyfully dedicate this House of God" (Ezra 6:16). A psalm therefore imbued with the joy of returning home because, once again, God has shown fidelity to the Covenant with his people of whom he is the father, the avenger, their "redeemer". Re-reading its own history, Israel can testify that God has always accompanied it in its struggle for freedom: "The LORD does justice to the oppressed, he raises up the afflicted". Israel experienced hunger, in the desert, during the Exodus and God sent manna and quails for its food: "To the hungry he gives bread" and only later did it understand that God always redeems the afflicted, heals the sick, lifts up the small and marginalised, opens the eyes of the blind and progressively reveals himself, through his prophets, to his people who seek him: "God loves the righteous". In this song, note the insistence on the name "Lord", which here translates the famous NAME of God revealed to Moses on Sinai, in the burning bush: it is the four consonants YHVH (two inhaled and two inspired) that indicate the permanent, active, liberating presence of God in the life of his people (Ex.3:13-15). Moreover, in the Bible, the expression 'your God' is a reminder of the Covenant with the chosen people: a Covenant to which the Lord has never failed, and Israel's prayer is addressed to the future, so when it evokes the past, it is to strengthen its expectation and hope. God communicated his name to Moses on Sinai in two ways. First with the unpronounceable four consonants, YHVH, which we often find in the Bible, particularly in this psalm, and which is translated as 'the Lord'. There is, however, a more elaborate formula, "Ehiè asher ehiè", which in Italian is rendered either as "Io sono chi sono", or "I will be who I will be", a way of expressing God's eternal presence alongside his people. The insistence on the future, "for ever" reinforces the commitment of the people who, with this psalm, not only recognise God's work on behalf of Israel, but also want to give themselves a course of action: if God has acted in this way towards us, we in turn must do the same, becoming the first witnesses of the Lord's love for the poor and excluded, a love that, through Israel, he intends to spread to the whole world. The Law of Moses and the Prophets was written to educate the people to progressively conform to God's mercy and, for this reason, it provided numerous rules of protection for widows, orphans, and foreigners, intending to make Israel a free people that respects the freedom of others. Finally, the prophets' appeals focus on two points (which perhaps surprise us): a fierce fight against idolatry, (as Elijah did) and appeals to justice and care for others, going so far as to make God say: "It is mercy I want, not sacrifices, the knowledge of God, not holocausts" (Hos 6:6); or again: "You have been told, O man, what is good, what the Lord requires of you: nothing but to respect right, to love faithfulness, and to walk humbly with your God" (Mi 6:8). Finally, we read in the book of Ben Sira: "The widow's tears run down the cheeks of God" (Si 35:18). For Israel, the tears of all those who suffer flow down the cheeks of God...and if we are close to God, they should flow down our cheeks too!

* Second Reading Heb. 9:24-28

The author of the letter to the Hebrews, which has been with us for a few Sundays, is addressing Christians of Jewish origin who perhaps feel nostalgia for the ancient cult, while in Christian practice there are no temples or bloody sacrifices. The author, wanting to prove that everything is now obsolete, takes up the realities and practices of the Jewish religion one by one. He speaks above all of the Temple, defined as the 'sanctuary' and points out that one thing is the true sanctuary, in which God resides, that is, heaven itself, quite another is the temple built by men, which is only a pale copy of the true sanctuary. The Jews were particularly proud, and rightly so, of the magnificent Temple of Jerusalem, but they did not forget that every human construction remains human and therefore, weak, imperfect, perishable. Moreover, no one in Israel claimed to enclose the presence of God in a temple, however immense, as the first builder of the Temple of Jerusalem, King Solomon already stated: "Could God really dwell on earth? The heavens themselves and the heavens of the heavens cannot contain you! How much less this House that I have built." (1 Kings 8:27). For Christians, the true Temple, the place where one encounters God, is not a building because the Incarnation of Christ changed everything: now the meeting place between God and man is Jesus Christ, the God made man. The Evangelist John narrates that Jesus took the liberty of driving out the money changers and cattle merchants for sacrifices from the Temple area, explaining then: "Destroy this Temple and in three days I will raise it up" and the disciples understood, after the Resurrection, that the Temple of which he spoke was his body. (Cf. Jn 2:13-21). In today's passage from the Epistle to the Hebrews the same thing is said: let us remain grafted into Jesus Christ, let us be nourished by his body, thus we are placed in the presence of God on our behalf. With his death Christ highlights the central role of the cross in the Christian mystery and a little later (Heb 10), the author will specify that Christ's death is only the culmination of a life entirely offered up and that when speaking of his sacrifice, one must mean "the sacred act that was his whole life" and not only the hours of his Passion. For the moment, the text before us speaks of Christ's Passion and his sacrifice, without any further details. It juxtaposes the sacrifice of Christ with that offered by the high priest of Israel, on the day of Yom Kippur ("Day of Forgiveness") when the high priest, entering alone into the Holy of Holies, pronounced the Holy Name (YHVH) and shed the blood of a bull (for his own sins) and that of a goat (for the sins of the people), solemnly renewing the Covenant with God. As the high priest left the Holy of Holies, the people, gathered outside, knew that their sins were forgiven. But this renewal of the Covenant was precarious, and had to be repeated every year, whereas the Covenant that Jesus Christ made with the Father in our name is perfect and final: on the Face of Christ on the cross, believers discover the true Face of God who loves his own to the end. We can no longer deceive ourselves; God is our Father because He is the Father of Jesus and in Christ we can live in the Covenant that God proposes to us: the New Covenant in Christ and there is no longer any room for fear of God's judgement because by professing "Jesus will come again to judge the living and the dead" (in our Creed), we proclaim that the word "judgement" is synonymous with salvation: "the Christ, having offered himself once to take away the sins of many, will appear a second time, no longer for sin, but for the salvation of those who wait for him" and it is right to affirm that Jesus Christ is "the high priest of the coming happiness", as the author states in ch. 9:11, a text that is proclaimed on the feast of the Body and Blood of Christ, in year B.

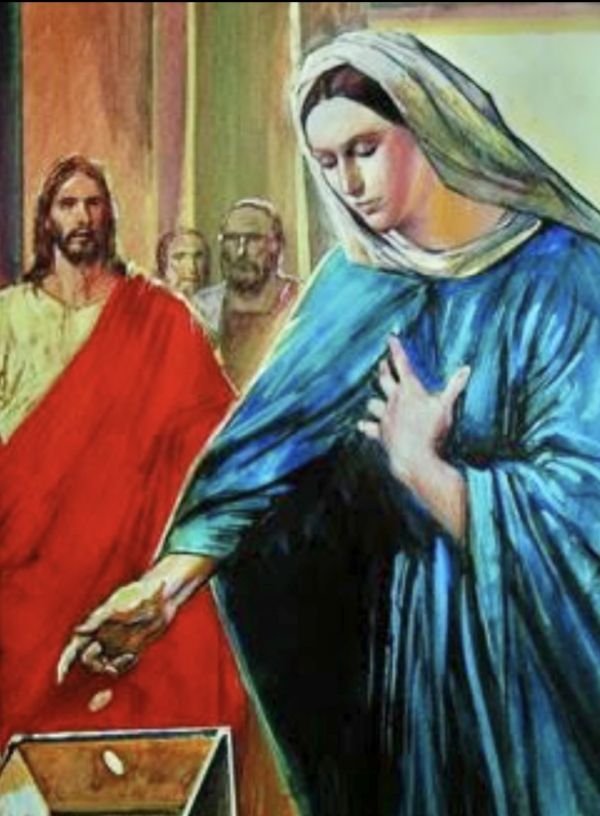

*Gospel Mark 12:38-44

"Beware of the scribes..." We are at the conclusion of the 12th chapter and are approaching the end of Mark's gospel, with the account of the Passion and Resurrection of Christ. Jesus dispenses the last advice to the apostles: He has already told them to have faith in God and "whatever you ask in prayer, have faith that you have obtained it and it will happen to you" (11:22-24). He then added: "See to it that no one deceives you" (13:5), while he now exhorts them to beware of the scribes (12:38) using the language of the prophets to stigmatise some of their attitudes without this meaning a total condemnation of their actions. At the time, the scribes were highly regarded because they commented and interpreted the Scriptures and preached, they sat in the Sanhedrin, the permanent court of Jerusalem that met in the Temple premises twice a week; they were therefore laymen who had studied the Law of Moses in specialised schools, becoming experts and some among them were called "doctors of the law" so that by respecting them, the Law itself was respected. Such respect made some people's heads swell as they demanded the first seats in the synagogues, with their backs to the Tablets of the Law and facing the public. In today's gospel, Jesus pays tribute to the scribe who had wisely replied, "You are not far from the Kingdom of God." (12:34), but adds a more general criticism by reacting to the hostility that some scribes, from the beginning of his public life, had shown him envy and jealousy. A growing distrust of Christ towards them becomes clear in Mark's gospel as their jealousy becomes hatred to the point of planning to kill Jesus after the expulsion of the merchants from the Temple. The chief priests, scribes and elders besiege him as he walks in the Temple asking him by what authority he teaches and performs miracles (11:27-28) and we will see during the passion Pilate himself realise this, as St Mark notes: "Pilate knew that the chief priests had handed him over to them out of envy" (15:10). Jesus, however, is not impressed by their hatred and rebukes them for something much more serious, namely, that they exploit their position by demanding payment from poor widows when they ask for legal advice: "They devour widows' houses and pray long to be seen. They will receive a more severe sentence" (12:40). It is at this point that a poor widow appears (12:42-43) in total destitution (12:44) because, not being entitled to her husband's inheritance, she depended on public charity. She approaches to lay down two pennies and Jesus points her out as an example to the disciples: 'Truly I say to you, this widow, so poor, has thrown more into the treasury than all others. For all have offered of their surplus. She, on the other hand, in her misery, threw into it all she had to live on" (12:43-44). The evangelist makes no comment, but it is understood that the widow's trust will be rewarded. The parallel with the widow of Sarepta is natural: just as she offered Elijah her last provisions, this widow laid down all her savings in the Temple, stripping herself of everything. Jesus invites us to reject the model of ostentation of some scribes with their thirst for honours and privileges, and exhorts us to imitate the humble and discreet generosity of the "poor widow" who leaves everything she has in the Temple. Several Church Fathers have interpreted it as a powerful symbol of humble and generous faith and genuine charity, not because she gives much but because she offers everything she has to live on, trusting God. This story, besides being a lesson in charity and trust, is also a reminder of authentic social justice, where love for God must always translate into care, help and love for the needy.