don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Christmas Day

Christmas Day 2025 [Midnight Mass]

May God bless you and may the Virgin Mary protect us. Best wishes for this holy Christmas Day of Christ. I offer for your consideration a commentary on the biblical texts of the midnight and daytime Masses.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (9:1-6)

To understand Isaiah's message in this text, one must read this verse, the last of chapter 8, which directly precedes it: 'God humbled the land of Zebulun and Naphtali in the past, but in the future he will glorify the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the nations' (v. 23). The text does not allow us to establish the date of its writing with precision, but we know two things with certainty: the political situation to which it refers, even if the text may have been written later. And we also know the meaning of the prophetic word, which seeks to revive the hope of the people. At the time evoked, the people were divided into two kingdoms: in the north, Israel, with its capital at Samaria, politically unstable; in the south, the kingdom of Judah, with its capital at Jerusalem, the legitimate heir to the Davidic dynasty. Isaiah preached in the South, but the places mentioned (Zebulun, Naphtali, Galilee, the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan) belong to the North. These areas – Galilee, the way of the sea, Transjordan – suffered a particular fate between 732 and 721 BC. In 732, the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III annexed these regions. In 721, the entire northern kingdom fell. Hence the image of 'the people walking in darkness', perhaps referring to the columns of deportees. To this defeated people, Isaiah announces a radical reversal: God will bring forth a light in the very regions that have been humiliated. Why do these promises also concern the South? Jerusalem is not indifferent to what is happening in the North: because the Assyrian threat also hangs over it; because the schism is experienced as a wound and there is hope for the reunification of the people under the house of David. The advent of a new king, the words of Isaiah ("A great light has risen...") belonged to the ritual of the sacred royal: every new king was compared to a dawn that brings hope for peace and unity. Isaiah therefore announces: the birth of a king ("A child is born for us..."), called "Prince of Peace", destined to restore strength to the Davidic dynasty and reunite the people. This certainty comes from faith in the faithful God, who cannot betray his promises. The prophecy invites us not to forget God's works: Moses reminded us, 'Be careful not to forget'. Isaiah said to Ahaz, 'Unless you believe, you will not be established' (Isaiah 7:9). The promised victory will be "like the day of Midian" (Judges 7): God's victory achieved through a small faithful remnant with Gideon. The central message is "Do not be afraid: God will not abandon the house of David." Today we could say: Do not be afraid, little flock, God does not abandon his plan of love for humanity, and light is believed in the night. Historical context: When Isaiah announces these promises, King Ahaz has just sacrificed his son to idols out of fear of war, undermining the very lineage of David. But God, faithful to his promises, announces a new heir who will restore the line of David: hope is not cancelled out by human sin.

Most important elements. +The context: Assyrian annexations (732–721 BC) devastating the northern regions. +Isaiah's words are a prophecy of hope for a people in darkness.

+The announcement is linked to the sacred royal line: the birth of a new Davidic king. +The promise concerns unity, peace and God's faithfulness to his covenant with David. +Victory will be God's work, like Gideon's victory. +Even Ahaz's sin does not nullify God's plan: God remains faithful.

*Responsorial Psalm (95/96)

The liturgy offers only a few verses from Psalm 95/96, but the entire psalm is filled with a thrill of joy and exultation. Yet it was composed in a historical period that was not at all exciting: what vibrates is not human enthusiasm, but the faith that hopes, that hope that anticipates what is not yet possessed. The psalm projects us to the end of time, to the blessed day when all peoples will recognise the Lord as the one God and place their trust in him. The image is grandiose: we are in the Temple of Jerusalem. The esplanade is filled with an endless multitude of people, gathered 'from the ends of the earth'. Everyone sings in unison: 'The Lord reigns!' It is no longer Israel's acclamation for an earthly king, but the cry of all humanity recognising the King of the world. And it is not only humanity that acclaims: the earth trembles, the seas roar, the countryside and even the trees of the forests dance. The whole of creation recognises its Creator, while man has often taken centuries to do so. The psalm also contains a criticism of idolatry: 'the gods of the nations are nothing'. Over the centuries, the prophets have fought the temptation to rely on false gods and false securities. The psalm reminds us that only the Lord is the true God, the One who 'made the heavens'. The reason why all peoples now flock to Jerusalem is that the good news has finally reached the whole world. And this was possible because Israel proclaimed it every day, recounting the works of God: the liberation from Egypt, the daily liberations from many forms of slavery, the most serious danger: believing in false values that do not save. Israel has received the immense privilege of knowing the one God, as the Shema proclaims: "The Lord is one."

But it has received this privilege in order to proclaim it: "You have been given to see, so that you may know... and make it known." Thanks to this proclamation, the good news has reached "the ends of the earth" and all peoples gather in the "house of the Father." . The psalm anticipates this final scene and, while waiting for it to come true, Israel sings it to renew its faith, revive its hope and find the strength to continue the mission entrusted to it.

Most important elements: +Psalm 95/96 is a song of eschatological hope: it anticipates the day when all humanity will recognise God. +The story describes a cosmic liturgy: humanity and creation together acclaim the Lord. +Strong denunciation of idolatry: the 'gods of the nations' are nothing. +Israel has the task of proclaiming God's works and his deliverance every day. +Its vocation: to know the one God and make him known. +The psalm is sung as an anticipation of the future, to keep the faith and mission of the people alive.

*Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul to Titus (2:11-14) and for the Dawn Mass (3:4-7)

Through Baptism, we are immersed in God's grace. The Cretans had a bad reputation even before St Paul's time. A poet of the 6th century BC, Epimenides of Knossos, called them "liars by nature, evil beasts, lazy bellies". Paul quotes this phrase and adds: "This is true!". And it was precisely because he was well aware of this difficult humanity that Paul founded a Christian community, which he then entrusted to Titus to organise and lead. The Letter to Titus contains the founder's instructions to the leaders of the young Church of Crete. Many scholars believe that the letter was written towards the end of the first century, after Paul's death, but it respects his style and is faithful to his theology. In any case, the difficulties of the Cretans must still have been very much alive. The letter — very short, just three pages — contains concrete recommendations for all categories of the community: elders, young people, men, women, masters, slaves, and even those in charge, who are admonished to be blameless, hospitable, just, self-controlled, and far from violence, greed, and drunkenness. It is a long list of advice that gives an idea of how much work still needed to be done. The central theological passage of the letter—the one proclaimed in the liturgy—explains the foundation of all Christian morality, namely that new life is born from Baptism. Paul links moral advice to a decisive statement: "The grace of God has been revealed for the salvation of all." The message is this: Behave well, because God's grace has been revealed, and this means that moral change is not a human effort, but a consequence of the Incarnation. When Paul says 'grace has been revealed', he means that God became man and, through Baptism, immersed in Christ, we are reborn: saved through the washing of regeneration and renewal in the Holy Spirit (Titus 3:5). We are not saved by our own merits, but by mercy, and God asks us to be witnesses to this. God's plan is the transformation of the whole of humanity, gathered around Christ as one new man. This goal seems distant, and unbelievers consider it a utopia, but believers know and confess that it is promised by God, and therefore it is a certainty. For this reason, we live "in the hope of the blessed hope and the manifestation of the glory of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ." The words that the priest pronounces after the Our Father in the Mass echo this very expectation: 'while we await the fulfilment of the blessed hope...'. This is not an escape from reality, but an act of faith: Christ will have the last word on history. This certainty nourishes the entire liturgy, and the Church already lives as a humanity already gathered in Christ and reaching towards the future, so that when the end comes, it will be possible to say: "They rose up as one man, and that man was Jesus Christ."

Historical note: When was the Christian community of Crete born? Two hypotheses: During Paul's transfer to Rome (Acts 27), the ship stopped at "Good Harbours" in the south of the island. But the Acts do not mention the founding of a community, and Titus was not present. During a fourth missionary journey after Paul's release: his first imprisonment in Rome was probably "house arrest"; once freed, Paul would have evangelised Crete on this last journey.

Important points to remember: +The Cretans were considered difficult, but Paul founded a community there anyway. +The Letter to Titus contains concrete instructions for structuring the nascent Church. +Christian morality arises from the Incarnation and Baptism, not from mere human effort. +God saves through mercy and asks for witness, not merit. +God's plan: to reunite humanity in Christ as one new man. +The expectation of the 'blessed hope' is certainty and sustains liturgical life.

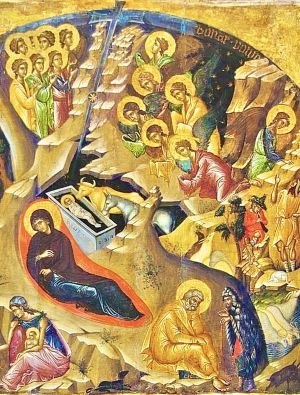

*From the Gospel according to Luke (2:1-14)

Isaiah, announcing new times to King Ahaz, speaks of the 'jealous love of the Lord' as the force capable of fulfilling the promise (Is 9:6). This conviction runs through the entire account of Jesus' birth in Luke's Gospel. The night in Bethlehem resounds with the angels' announcement: "Peace to those whom the Lord loves," which would be better said as "Peace to those whom God loves." In fact, there are no "loved and unloved people" because God loves everyone and gives his peace to all. God's entire plan is encapsulated in this phrase, which John summarises as follows: "God so loved the world that he gave his only Son" (Jn 3:16). Faced with a God who presents himself as a newborn baby, there is nothing to fear: perhaps God chose to be born in this way so that our fears of him would fall away forever. Like Isaiah in his time, the angel also announces the birth of the expected King: "Today a Saviour, Christ the Lord, is born to you in the city of David. He is the son promised in Nathan's prophecy to David (2 Sam 7): a stable lineage, a kingdom that lasts forever. This is why Luke insists on Joseph's origins: he belongs to the house of David and, for the census, he goes up to Bethlehem, a place also indicated by the prophet Micah as the homeland of the Messiah, who will be the shepherd of the people and the bringer of peace (Mic 5). The angels therefore announce "great joy" . But what is surprising is the contrast between the greatness of the Messiah's mission and the smallness , the minority of his conditions: the 'heir of all things' (Heb 1:2) is born among the poor, in the dim light of a stable; the Light of the world appears almost voluntarily hiding himself; the Word that created the world wants to learn to speak like any newborn baby. And in this light, it is not surprising that many "did not recognise him". The sign of God is not in the exceptional but in the simple and poor everyday life: it is there that the mystery of the Incarnation is revealed, and the first to recognise it are the little ones and the poor, because God, the "Merciful One", allows himself to be attracted only by our poverty. Bending down over the manger in Bethlehem, then, means learning to be like Him, because it is from this humble 'cathedra' that the almighty God communicates to us the power to become children of God (Jn 1:12).

*Final note. The firstborn, a legal term, had to be consecrated to God, and in biblical language this does not mean that other children came after Jesus, but that there were none before him. Bethlehem literally means 'house of bread'; the Bread of Life is given to the world. The titles attributed to Jesus recall those attributed to the Roman emperor venerated as 'god' and 'saviour', but the only one who can truly bear these titles is the newborn child of Bethlehem.

Key points to remember: +Isaiah and the 'jealous love of the Lord': the promise of a future king (Isaiah 9:6). +Announcement of the angels: 'Peace to men because God loves them'. +The heart of the Gospel: 'God so loved the world that he gave his only Son' (John 3:16). +The newborn child eliminates all fear of God: God chooses the way of fragility. +Fulfillment of promises +Nathan's prophecy to David (2 Sam 7). +Micah's prophecy about Bethlehem (Mic 5). +Joseph: Davidic descent. +Surprising contrast: greatness of the Messiah vs. extreme poverty of birth. +Christological titles: "Heir of all things" (Heb 1:2). "Light of the world". "Word" who becomes a child. +The sign of God is poor normality: the mystery of the Incarnation in everyday life +The poor and the little ones recognise him first. +Our vocation: to become children of God (Jn 1:12) by imitating his mercy.

St Ambrose of Milan – Brief commentary on Lk 2:1-14 “Christ is born in Bethlehem, the ‘house of bread’, so that it is understood from the beginning that He is the Bread that came down from heaven. His manger is the sign that He will be our nourishment. The angels announce peace, because where Christ is, there is true peace. And the shepherds are the first to receive the news: this means that grace is not given to the proud, but to the simple. God does not manifest himself in the palaces of the powerful, but in poverty; thus he teaches that those who want to see the glory of God must start from humility."

Christmas Day 2025 [Mass of the Day]

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (52:7-10)

The Lord comforts his people. The cry, "Break forth together into songs of joy, ruins of Jerusalem," places Isaiah's text precisely in the time of the Babylonian Exile (587 BC), when Jerusalem was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar's army. The devastated city, the deportation of the people, and the long wait for their return had led to discouragement and loss of hope. In this context, the prophet announces a decisive turning point: God has already acted. The words "Comfort, comfort my people" become a certainty that the return is imminent. Isaiah imagines two symbolic figures: the messenger, who runs to announce the good news, and the watchman, who sees the liberated people advancing from the walls of Jerusalem. In the ancient world, the messenger on foot was the only means of rapid communication, while the watchman kept vigil from the top of the walls or hills. Thus Isaiah sings of the beauty of the footsteps of those who announce peace, salvation and good news. Not only is the people saved, but the city will also be rebuilt: for this reason, even the ruins are invited to rejoice. The liberation of Israel manifests the power of God, who shows 'his holy arm'. As in the Exodus from Egypt, God intervenes forcefully to redeem his people. Isaiah uses the term 'He has redeemed Jerusalem' (Go'el): God is the closest relative who liberates, not out of self-interest, but out of love. During the exile, the people come to a fundamental discovery: the election of Israel is not an exclusive privilege, but a universal mission. God's salvation is intended for all nations, so that every people may recognise the Lord as Saviour. Re-read in the light of Christmas, this announcement finds its fulfilment: God has definitively shown his holy arm in Jesus Christ. Today, the mission of believers is that of the messenger: to announce peace, the good news, and to proclaim to the world that God reigns.

Most important elements in the text: +God (the Lord) is the true protagonist: Go'el, liberator, king who returns to Zion. + Israel, the chosen people, freed from exile, is called to a universal mission. +The messenger is the figure who announces the good news, peace and salvation. +The watchman, the one who keeps watch, recognises the signs of salvation and announces the coming of the Lord. +Jerusalem (the holy city) destroyed but destined for reconstruction; symbol of the restored people.

*Responsorial Psalm (97/98)

As always, only a few verses are proclaimed, but the commentary covers the entire psalm, whose theme is: the people of the Covenant... at the service of the Covenant of peoples. All the ends of the earth have seen the victory of our God': it is the people of Israel who speak and say 'our God', thus affirming the unique and privileged bond that unites them to the God of the universe. However, Israel has gradually come to understand that this relationship is not an exclusive possession, but a mission: to proclaim God's love to all people and to bring the whole of humanity into the Covenant. The psalm clearly expresses what can be defined as 'the two loves of God': faithful love for his chosen people, Israel; universal love for all nations, that is, for the whole of humanity. On the one hand, it proclaims that the Lord has made known his victory and his justice to the nations; on the other hand, it recalls his faithfulness and love for the house of Israel, formulas that recall the whole history of the Covenant in the desert, when God revealed himself at Sinai as a God of love and faithfulness (Ex 19-24). The election of Israel, therefore, is not a selfish privilege, but a fraternal responsibility: to be an instrument for all peoples to enter into the Covenant. As André Chouraqui stated, the people of the Covenant are called to become instruments of the Covenant of peoples. This universal openness is also emphasised by the literary structure of the psalm, constructed according to the process of 'inclusion'. The central phrase, which speaks of God's faithfulness to Israel, is framed by two statements that concern all humanity: at the beginning, the nations; at the end, the whole earth. In this way, the text shows that the election of Israel is central, but oriented towards radiating salvation to all. During the Feast of Tabernacles in Jerusalem, Israel acclaims the Lord as king, aware that it is already doing so on behalf of all humanity, anticipating the day when God will be recognised as king of the whole earth. The psalm thus insists on a second fundamental dimension: the kingship of God. The acclamation is not a simple song, but a true cry of victory (teru‘ah), similar to that which was raised on the battlefield or on the day of a king's coronation. The theme of victory returns several times: the Lord has won with his holy arm and his mighty hand, he has manifested his justice to the nations, and the whole earth has seen his victory. This victory has a twofold meaning. On the one hand, it recalls the liberation from Egypt, God's first great act of salvation, remembered in the images of his mighty arm and the wonders performed in the crossing of the sea. On the other hand, it announces the final and eschatological victory, when God will triumph definitively over every force of evil. For this reason, the acclamation is full of confidence: unlike the kings of the earth, who disappoint, God does not disappoint. Christians, in the light of the Incarnation, can proclaim with even greater force that the King of the world has already come and that the Kingdom of God, the Kingdom of love, has already begun, even if it has yet to be fully realised.

Important elements of the text: +The privileged relationship between Israel and God, +Israel's universal mission in the service of humanity. +The "two loves of God": for Israel and for all nations. +The Covenant as God's faithfulness and love in history. +The literary structure of "inclusion". +The proclamation of God's kingship and the cry of victory (teru'ah) and liturgical language. +The memory of the liberation from Egypt and the expectation of God's final victory at the end of time. +The Christian reinterpretation in the light of the Incarnation. +The reference to musical instruments of worship. + The image of God's power, which at Christmas is manifested in the fragility of a child.

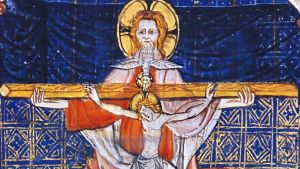

*Second Reading from the Letter to the Hebrews (1:1-6)

The statement "God spoke to the fathers through the prophets" shows that the Letter to the Hebrews is addressed to Jews who have become Christians. Israel has always believed that God revealed himself progressively to his people: since God is not accessible to man, it is He who takes the initiative to make himself known. This revelation takes place through a gradual process of teaching, similar to the education of a child, as Deuteronomy reminds us: God educates his people step by step. For this reason, in every age, God has raised up prophets, considered to be the 'mouth of God', who have spoken in a way that was understandable to their time. He has spoken 'many times and in many ways', forming his people in the hope of salvation. With Jesus Christ, however, we enter the time of fulfilment. The author of the Letter to the Hebrews distinguishes two great periods: the time before Christ and the time inaugurated by Christ. In Jesus, God's merciful plan of salvation finds its full fulfilment: the new world has already begun. After the resurrection, the early Christians gradually came to understand that Jesus of Nazareth was the expected Messiah, but in an unexpected form. Expectations were different: a Messiah-king, a Messiah-prophet, a Messiah-priest. The author affirms that Jesus is all of these together.

Jesus is the prophet par excellence: while the prophets were the voice of God, Jesus is the very Word of God, through whom everything was created. He is the reflection of the Father's glory and its perfect expression: whoever sees Him sees the Father. As a priest, Jesus re-establishes the Covenant between God and humanity. Living in perfect filial relationship with the Father, he accomplishes the purification of sins. His priesthood does not consist of external rites, but of a life totally given in love and obedience to the Father. Jesus is also the Messiah-King. The royal prophecies apply to him: he sits at the right hand of the divine Majesty and is called the Son of God, the royal title par excellence. His kingdom surpasses that of the kings of the earth: he is lord of all creation, superior even to the angels, who adore him. This implicitly affirms his divinity. To be Christ, therefore, means to be prophet, priest and king. This text also reveals the vocation of Christians: united with Christ, they share in his dignity. In baptism, believers are made participants in Christ's mission as prophet, priest and king. The fact that this passage is proclaimed at Christmas invites us to recognise all this depth in the child in the manger: He carries within himself the mystery of the Son, the King, the Priest and the Prophet, and we live in Him, with Him and for Him.

Most important elements of the text: +The progressive revelation of God. +The role of prophets in the history of Israel. +Jesus as the definitive fulfilment of revelation. +Christ, the Word of God and reflection of his glory. +Christ, priest who re-establishes the Covenant. +Christ, king, Son of God and Lord of creation. +The unity of the three functions: prophet, priest and king. +The participation of Christians in this mission through baptism

*From the Gospel according to John (1:1-18)

Creation is the fruit of love. 'In the beginning': John deliberately takes up the first word of Genesis ('Bereshit'). It does not indicate a mere chronological succession, but the origin and foundation of all things. "In the beginning was the Word": everything comes from the Word, the Word of love, from the dialogue between the Father and the Son. The Word is "turned towards God" (pros ton Theon), symbolising the attitude of dialogue: looking the other in the eye, opening oneself to encounter. Creation itself is the fruit of this dialogue of love between the Father and the Son, and man is created to live it. We are the fruit of God's love, called to a filial dialogue with Him. Human history, however, shows the rupture of this dialogue: the original sin of Adam and Eve represents distrust in God, which interrupts communion. Conversion, that is, 'turning around', allows us to reconcile dialogue with God. The future of humanity is to enter into dialogue. Christ lives this dialogue with the Father perfectly: He is humanity's 'Yes' to the Father. Through Him, we are reintroduced into the original dialogue, becoming children of God for those who believe in Him. Trust in God ("believing") is the opposite of sin: it means never doubting God's love and looking at the world through His eyes. The Incarnate Word (The Word became flesh) shows that God is present in concrete reality; we do not need to flee from the world to encounter Him. Like John the Baptist, we too are called to bear witness to this presence in our daily lives.

Main elements of the text: +Creation as the fruit of the dialogue of love between the Father and the Son: + In the beginning indicates origin and foundation, not just chronology. +The Word as the creative Word and the beginning of dialogue. +Man created to live in filial dialogue with God

and The breaking of dialogue in original sin. +Conversion as a 'half-turn' to reconcile the relationship with God. +Christ as perfect dialogue and humanity's 'Yes' to the Father. +Becoming children of God through faith. +The presence of God in concrete reality and in the flesh of the Word. +The call of believers to be witnesses of God's presence

Commenting on John's Prologue, St Augustine writes: 'The Word was not created; the Word was with God, and everything was made through Him. He is not merely a message, but the very Wisdom and Love of God who communicates himself to men." Augustine thus emphasises that creation and humanity are not an accident, but the fruit of God's eternal love, and that man is called to respond to this love in dialogue with Him.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

Contrasting Presentation: scrutinizing what is not being studied

(Mal 3:1-4 Heb 2:14-18 Lk 2:22-40)

The Lk’s Gospel passage narrates the surprising response of the Father to the prophecy of the last of the minor prophets (Mal 3,1-4).

An eloquent and peremptory manifestation of the power of the Israel’s God and the submission of those who did not fulfill the Law was expected.

Everyone imagined witnessing the triumphal entry of a boss surrounded by military leaders or angelic hosts (Mal 3:1).

Commander who would subjugate the pagan peoples, brought their goods to the ‘holy city’, guaranteed many slaves, and imposed observance.

Jesus? Here he is yes in the Temple, but defenceless and accompanied by insignificant people.

No one notices them, although at all hours the sacred place was swarming with visitors.

So it’s not enough to be a devoted person to realize the presence of the Lord. But how to break through the wall of contrary appearances?

With the help of particularly sensitive people, who want to tell us something, because they are more able to understand the Unknown.

They are those who do not set their own intentions, current dreams, habitual expectations against the creative Design of the Most High - only demanding help from God to achieve them.

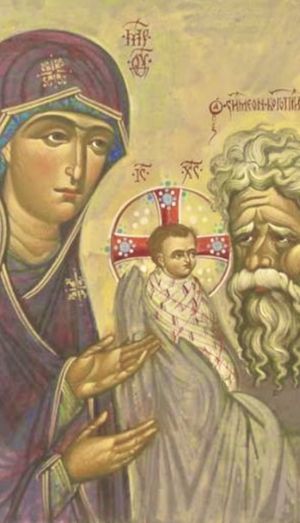

Here then rise Simeon and Anna, men and women from both inside and outside the Temple, who attempt to block the small domestic procession [Lk 2,28.38 Greek text].

The Holy Family must embark on a completely different Way - which will lead it to unforeseen growth.

Nobody should follow up legalist conventions based on culturally calibrated purisms and rites of social passage, which circumvent and block the evolutionary mechanisms brought about by surprises.

Women and men animated by the Spirit break in like ‘strangers’: they always try to prevent the "same" useless rite: it claimed to transform and reduce into son of Abraham the One who had been announced as the Son of God.

If the goal is the triumph of life, history must not prevail over Revelation. Uniqueness that manifests itself in what is happening and is proposed even dimly, now.

The ‘unveiling’ is here; not something to conquer, nor a race for “excellence”. It’s the Present that opens an arc of full existence.

Thus in Mary: the Mother, figure of that more sensitive and original remnant of Israel - compared to all the people of expectations, still sterile.

The repetitive world, therefore content with itself but now without new momentum, is challenged by a contrast (vv. 34-35).

It’s the reversal that shatters the outcome that everyone had in mind.

In the figure of «the innocent, glory of his people», resides a Light that illuminates everyone (v.32).

Spirit of childhood and simple immediacy that becomes the «redemption of Jerusalem» (v.38), that is, of the institution.

It’s another Story, an unsuspected ‘time of the soul’... that have turned the ancient root into a sapling. And the Jesse trunk in new sprout (Is 11: 1).

Young Gift, without our knowledge. But that recovers the great Desires of each - instead of the “compliant” and reduced ways, which even today in the time of the crisis lose us without posing.

[Presentation of the Lord, February 2]

[Octave of Christmas, Liturgy of December 29]

Church of the little ones

Without stopping in the middle, and without fashion. New Light

(Mal 3:1-4; Heb 2:14-18; Lk 2:22-40)

The context of Mal 3:1-4 is harrowing: the priests had reduced the temple to a bank; the professional worshippers were acting as functionaries, disregarding sincere adherence.

That Child is a reminder that God ceaselessly comes with his smoldering fire (Mal 3:2-3) not only to work a purification, an improvement, an enhancement, a mending, a mending, a parenthesis.

It does not burst in to make the same reality more current, or the identical formal and condescending contents more sympathetic. It comes to replace them.

It does not come to refine, but to open up. It comes not to affect, but to supplant. Not to bless tamed situations, but to denounce them.

Perhaps He comes to return us to the "ancient days", to the "distant years" - but not as imagined by Mal 3:4 - but to fly over the same swamp of the usual religion, the one with its head always turned back to investigate the past.

Nor does he advocate abstract, disembodied figures that distract attention; even if they were fashionable ['current' but evasive or personally oppressive, incapable of igniting reality from within].

Henceforth he manifests himself living, opening wide the doors of our sanctuary - no longer "subject to bondage for life" (Heb 2:15; Second Reading).

"For he cares not for the angels" (Heb 2:16), always available but without any instances of precisely personal impetus - without natural passions, lacking in independence - and with his brain always there, in the sacred.

The Gospel passage from Lk recounts the Father's surprising response to the predictions of fulfilment regarding the messianic prophecies.

An eloquent and peremptory manifestation of the power of the God of Israel and the submission of those who did not fulfil the Law was expected.

Everyone imagined that they would witness the triumphal entry of a leader - surrounded by military leaders or angelic hosts (Mal 3:1) - who would subjugate the pagans by bringing their possessions into the holy city, grant the chosen people many slaves, and enforce observance.

Jesus? Here he is in the Temple, but helpless; accompanied by insignificant people. No one notices them, although at all hours the holy place is swarming with visitors.

It is not enough to be pious and devout people to realise the presence of Christ - to see God himself, one's brothers, things, with the eyes of the Father.

How do we break through the wall of closed customs - how do we break through the artificial world of contrary appearances, to turn to the creative Unknown?

Lk answers: with the help of particularly sensitive people, capable of understanding the New Project.

They are those who do not set trivial intentions or current dreams against the Design of the Most High; the habitual expectations (of others) - demanding from the Lord only the help to realise them.

Here then arise Simeon and Anna (vv.25.36-38), women and men coryphaeans of the most sensitive authentic People, thanks to excellent work on the soul.

Coming both from inside and outside the Temple - such prophets attempt to block (vv.28.38 Greek text) the small family procession, still bound by Judaic conventions (vv.21-23).

Compared to cultic and legalistic stereotypes, the members of the holy family must take a different, conscious Path.

A path that will lead it to unforeseen growth, for the benefit of all.

Thus, the Tiny Holy Remnant of Spirit-animated women and men burst in (always) as if they were strangers...

People of tiny worshippers, of genuine outsiders, who even try to prevent the 'same' useless clan ritual!

A gesture that pretended - again - to transform (and reduce) into an obsequious son of Abraham the One who had been announced as the Son of God.

In short, in the figures of Simeon and Anna, Lk wants to convey to us a fundamental teaching.

If the goal is the triumph of life, past history must not take precedence over unheard-of revelation.

Divine Oneness is manifested in what happens.

The Exceptionality of the Spirit proposes itself (dimly) now.

Unexpectedness to which we are called to give full voice - and echo.

The unveiling is now.

The 'here' immediately opens an arc of full existence.

[No more repeating 'how we should be' according to customs or fathers...].

Where everything is combined, we will not find the answers that solve real problems, nor magic times - those that motivate us.

Genuine God souls are not concerned with pandering to obligations, but rather with living intensely in the present moment with the energy that shapes the future, without hesitating with the excesses of control.

Stepping out of the normality of the established way - even through labour pains (vv.34-35) - creates the space to welcome the Newness that saves.

Along the way, those thoughts and duties that no longer correspond to one's destiny will be defused, will evaporate of their own accord.

So in Mary: Mother icon of the whole Church of true expectations - cut off (v.35) from the habitual crowd.

She has laid down all dependencies.

And the Innocent One is the glory of the 'nation', in Spirit - for she comes forth!

In her unpredictable and healthy figure resides a Light that enlightens all (v.32).

A trait of childhood and simple immediacy that becomes the "redemption of Jerusalem" (v.38).

It is in fact a Light that produces conflict with officialdom, a profound Splendour destined for all time - while the astute do not want to know about losing coordinates, roles, positions.

A "sword" (v.35) that in Mother Israel will bring about lacerations between those who open themselves to the torch of the Gospel and others who vice versa.

Lk has in mind community situations, where believers in Christ are discarded by friends and families from different cultural backgrounds (Lk 12:51-53).

But the awaited and true Messiah must be delivered to the world - although those best prepared to recognise him are the members of the smallest tribe of Israel [Asher, in the figure of Anna: vv.36-38].

These are the same prophets who in life vibrated for one great Love (vv.36-37), then experienced the absence of the Beloved - until they recognised him in Christ. Rejoicing in surprise; grasping personal correspondences within themselves, in the Spirit; rejoicing, praising the Gift of God (v.38).

The passage concludes with the return to Nazareth (vv.39-40) and the note concerning Jesus' own growth "in wisdom, stature and grace" [Greek text].

Moral: we are not in this world to cling to shadows and blocks of the past, with its perennial feelings - same old moods, same prevailing thoughts, same way of doing things (even the little things).

Mechanisms and comparisons that close off our days, our whole life and the emotional space of passions - clipping the wings of testimonies that want to override the course recognised since our ancestors.

Conversely, this is precisely the great Challenge that activates the young Rebirth of the Dream of God. And launches us into the transition from religious sense to personal Faith.

Such is the only energy that awakens, arouses enthusiasm, communicates simple virtue, sweeps away the layers of dust that still cover us with conformism without intimate momentum.

The recalcitrant and collective ways of taking to the field [more or less 'moral'] point at, deviate from, overload our essence - appealing to the fear of being rejected.

To slip effortlessly into the conventions and manners of our local culture [i.e. à la page] we often risk losing the Calling by Name, the unrepeatability of the path that vibrates within and truly belongs to us.

With respect to the 'religious' guerrilla warfare that we carry on even with ourselves, we need a respite from the common forms - even devout; cultic and purist, or glamorous.

Here comes a break from the social self-image: to allow us to abandon external and toxic forms, to recover silenced energies.

And to launch ourselves into new experiences from the soul [which is not wrong] - which we want to and are called upon to espouse, with enthusiasm, without first stepping into a role.

The Expected

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

On today’s Feast we contemplate the Lord Jesus, whom Mary and Joseph bring to the Temple “to present him to the Lord” (Lk 2:22). This Gospel scene reveals the mystery of the Son of the Virgin, the consecrated One of the Father who came into the world to do his will faithfully (cf. Heb 10:5-7).

Simeon identifies him as “a light for revelation to the Gentiles” (Lk 2:32) and announces with prophetic words his supreme offering to God and his final victory (cf. Lk 2:32-35). This is the meeting point of the two Testaments, Old and New. Jesus enters the ancient temple; he who is the new Temple of God: he comes to visit his people, thus bringing to fulfilment obedience to the Law and ushering in the last times of salvation.

It is interesting to take a close look at this entrance of the Child Jesus into the solemnity of the temple, in the great comings and goings of many people, busy with their work: priests and Levites taking turns to be on duty, the numerous devout people and pilgrims anxious to encounter the Holy God of Israel. Yet none of them noticed anything. Jesus was a child like the others, a first-born son of very simple parents.

Even the priests proved incapable of recognizing the signs of the new and special presence of the Messiah and Saviour. Alone two elderly people, Simeon and Anna, discover this great newness. Led by the Holy Spirit, in this Child they find the fulfilment of their long waiting and watchfulness. They both contemplate the light of God that comes to illuminate the world and their prophetic gaze is opened to the future in the proclamation of the Messiah: “Lumen ad revelationem gentium!” (Lk 2:32). The prophetic attitude of the two elderly people contains the entire Old Covenant which expresses the joy of the encounter with the Redeemer. Upon seeing the Child, Simeon and Anna understood that he was the Awaited One.

The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple is an eloquent image of the total gift of one’s life for all those, men and women, who are called to represent “the characteristic features of Jesus — the chaste, poor and obedient one” (Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation, Vita Consecrata, n. 1) in the Church and in the world, through the evangelical counsels. For this reason Venerable John Paul II chose today’s Feast to celebrate the Annual World Day of Consecrated Life.

In this context, I would like to offer a cordial and appreciative greeting to Archbishop João Braz de Aviz, whom I recently appointed Prefect of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, along with the Secretary and the co-workers. I also greet with affection the Superiors General present and all the consecrated people.

I would like to suggest three brief thoughts for reflection on this Feast. The first: the evangelical image of the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple contains the fundamental symbol of light; the light that comes from Christ and shines on Mary and Joseph, on Simeon and Anna, and through them, on everyone. The Fathers of the Church connected this radiance with the spiritual journey. The consecrated life expresses this journey, in a special way, as “philokalia”, love of the divine beauty, a reflection of God’s divine goodness (cf. ibid., n. 19). On Christ’s Face the light of such beauty shines forth.

“The Church contemplates the transfigured face of Christ in order to be confirmed in faith and to avoid being dismayed at his disfigured face on the Cross.... she is the Bride before her Spouse, sharing in his mystery and surrounded by his light. This light shines on all the Church’s children.... But those who are called to the consecrated life have a special experience of the light which shines forth from the Incarnate Word. For the profession of the evangelical counsels makes them a kind of sign and prophetic statement for the community of the breth-ren and for the world” (ibid., n. 15).

Secondly, the evangelical image portrays the prophecy, a gift of the Holy Spirit. In contemplating the Child Jesus, Simeon and Anna foresee his destiny of death and Resurrection for the salvation of all peoples and they proclaim this mystery as universal salvation.

The consecrated life is called to bear this prophetic witness, linked to its two-fold contemplative and active approach. Indeed consecrated men and women are granted to show the primacy of God, passion for the Gospel practised as a form of life and proclaimed to the poor and the lowliest of the earth.

“Because of this pre-eminence nothing can come before personal love of Christ and of the poor in whom he lives.... True prophecy is born of God, from friendship with him, from attentive listening to his word in the different circumstances of history” (ibid., n. 84).

In this way the consecrated life in its daily experience on the roads of humanity, displays the Gospel and the Kingdom, already present and active.

Thirdly, the evangelical image of the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple demonstrates the wisdom of Simeon and Anna, the wisdom of a life completely dedicated to the search for God’s Face, for his signs, for his will; a life dedicated to listening to and proclaiming his word. “Faciem tuam, Domine, requiram: ‘Your face, Lord, do I seek’ (Ps 27 [26]:8).... Consecrated life in the world and in the Church is a visible sign of this search for the face of the Lord and of the ways that lead to the Lord (cf. Jn 14:8) .... The consecrated person, therefore, gives witness to the task, at once joyful and laborious, of the diligent search for the divine will” (cf. Congregation for the Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, Instruction The Service of Authority and Obedience. Faciem tuam, Domine, requiram [2008], n. 1).

Dear brothers and sisters, may you be assiduous listeners to the word, because all wisdom concerning life comes from the word of the Lord! May you seek the word, through lectio divina, since consecrated life “is born from hearing the word of God and embracing the Gospel as its rule of life. A life devoted to following Christ in his chastity, poverty and obedience thus becomes a living ‘exegesis’ of God’s word. The Holy Spirit, in whom the Bible was written, is the same Spirit who illumines the word of God with new light for the Founders and Foundresses. Every charism and every Rule springs from it and seeks to be an expression of it, thus opening up new pathways of Christian living marked by the radicalism of the Gospel” (Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Verbum Domini, n. 83).

Today, especially in the more developed societies, we live in a condition often marked by a radical plurality, by the progressive marginalization of religion in the public sphere and by relativism which touches the fundamental values. This demands that our Christian witness be luminous and consistent and that our educational effort be ever more attentive and generous.

May your apostolic action, in particular, dear brothers and sisters, become a commitment of life that with persevering enthusiasm attains to Wisdom as truth and as beauty, the “splendour of the truth”. May you, with the wisdom of your life and with trust in the inexhaustible possibilities of true education, guide the minds and hearts of the men and women of our time towards a “good life according to the Gospel”.

At this moment, my thoughts turn with special affection to all of the consecrated men and women throughout the world and I entrust them to the Blessed Virgin Mary:

O, Mary, Mother of the Church,

I entrust all consecrated people to you,

that you may obtain for them the fullness of divine light:

may they live in listening to the Word of God,

in the humility of following Jesus, your Son and our Lord,

in the acceptance of the visit of the Holy Spirit,

in the daily joy of the Magnificat,

so that the Church may be edified by the holy lives of these sons and daughters of yours,

in the commandment of love. Amen.

[Pope Benedict, Vespers of the Presentation 2 February 2011]

"Arise, ye ancient gates, and let the King of glory enter" (Ps 24:7)

With these words from the psalm, the liturgy of today's feast greets Jesus, born in Bethlehem, as he crosses the threshold of the temple in Jerusalem for the first time. Forty days after his birth, Mary and Joseph take him to the temple, to fulfil the law of Moses: "Every first-born male shall be holy to the Lord" (Lk 2:23; cf. Ex 13:2, 11).

The evangelist Luke emphasises that Jesus' parents are faithful to the law of the Lord, which advised the presentation of the newborn and prescribed the purification of the mother. However, it is not on these rites that the word of God intends to draw our attention, but on the mystery of the temple that today welcomes the one whom the old Covenant promised and the prophets awaited.

For him the temple was destined. The day was to come when he would enter it as "the angel of the covenant" (cf. Ml 3:1) and reveal himself as "the light to enlighten the nations and the glory of the people (of God), Israel" (Lk 2:32).

2. Today's feast is like a great anticipation: it anticipates Easter. In the liturgical texts and signs, in fact, we glimpse, almost in a solemn messianic announcement, what is to be fulfilled at the end of Jesus' mission in the mystery of his Passover. All those present in the temple of Jerusalem find themselves to be almost unconscious witnesses of the foretaste of the Passover of the New Covenant, of an event that is now at hand in the mysterious Child, an event that will give new meaning to everything.

The doors of the sanctuary open to the wondrous king, who "is here for the ruin and resurrection of many in Israel, a sign of contradiction" (Lk 2:34).

At the moment, nothing reveals his kingship. That forty-day-old infant is a normal child, the son of poor parents. Those closest to him know that he was born in a stable near Bethlehem. They remember the heavenly songs and the visit of the shepherds, but how can they think, even those closest to them, even Mary and Joseph, that this child - according to the words of the Letter to the Hebrews - is destined to take care of Abraham's offspring, the only high priest before God to atone for the sins of the world (cf. Heb 2:16-17)?

In fact, the presentation of this child in the temple, as one of the first-born sons of the families of Israel, is precisely a sign of this; it is the announcement of all the experiences, sufferings and trials to which he himself will undergo in order to come to the aid of mankind, to those men whom life very often puts to the test.

It will be he, the merciful, unique and eternal Priest of God's new and unchanging Covenant with humanity, who will reveal divine mercy. He, the revealer of the Father, who "so loved the world" (Jn 3:16). He light, the light that illuminates every man, in the succession of the various stages of history.

But, again for this reason, in every age Christ becomes "a sign of contradiction" (Lk 2:34). Mary, who today, as a young mother, carries him in her arms, will become, in a singular way, a sharer in his sufferings: the Virgin's soul will be pierced by a sword, and her suffering together with the Redeemer will serve to bring truth into the hearts of men (cf. Lk 2:35).

3. The temple of Jerusalem thus becomes the theatre of the messianic event. After the night of Bethlehem, here is the first eloquent manifestation of the mystery of the divine Christmas. It is a revelation that comes as if from the depths of the Old Covenant.

For who is Simeon, whose words inspired by the Holy Spirit resound under the vault of the temple in Jerusalem? He is one of those who "waited for the comfort of Israel", whose expectation was filled with unwavering faith (cf. Lk 2:25). Simeon lived with the certainty that he would not die before he saw the Lord's Messiah: a certainty coming from the Holy Spirit (cf. Lk 2:26).

And who is Anna, daughter of Phanuel? An elderly widow, called by the Gospel "prophetess", who never left the temple and served God with fasting and prayers day and night (cf. Lk 2:36-37).

4. The characters, who take part in the event commemorated today, are all included in a great symbol: the symbol of the temple, the temple of Jerusalem, built by Solomon, whose pinnacles indicate the ways of prayer for every generation of Israel. The sanctuary is indeed the crowning point of the people's journey through the desert towards the Promised Land, and expresses a great expectation. The whole of today's liturgy speaks of this expectation.

The destiny of the temple in Jerusalem, in fact, does not end with representing the Old Covenant. Its true meaning from the beginning was the expectation of the Messiah: the temple, built by men for the glory of the true God, would have to give way to another temple, which God himself would build there, in Jerusalem.

Today, he comes to the temple who says he will fulfil its destiny and must 'rebuild' it. One day, while teaching in the temple, Jesus would say that that building built by human hands, already destroyed by invaders and rebuilt, would be destroyed again, but that destruction would mark the beginning of an indestructible temple. The disciples, after his resurrection, understood that he called his body a "temple" (cf. Jn 2:20-21).

5. Today, then, dear friends, we are experiencing a singular revelation of the mystery of the temple, which is one: Christ himself. The sanctuary, even this Basilica, must not so much serve worship as holiness. Everything to do with blessing, especially the dedication of sacred buildings, even in the New Covenant, expresses the holiness of God, who gives himself to man in Jesus and the Holy Spirit.

God's sanctifying work touches temples made by the hand of man, but its most appropriate space is man himself. The consecration of buildings, though architecturally magnificent, is a symbol of the sanctification that man draws from God through Christ. Through Christ, every person, man or woman, is called to become a living temple in the Holy Spirit: a temple in which God truly dwells. Of such a spiritual temple Jesus spoke in his conversation with the Samaritan woman, revealing who are the true worshippers of God, those who give glory to him "in spirit and in truth" (cf. Jn 4:23-24).

6. Dearly beloved, St Peter's Basilica is gladdened today by your presence, dear Brothers and Sisters, who, coming from so many different communities, represent the world of consecrated persons. It is a beautiful tradition that it is you who form the holy assembly in this solemn celebration of Christ "Light of the Gentiles". In your hands you carry burning candles, in your hearts you carry the light of Christ, spiritually united with all your consecrated brothers and sisters in every corner of the earth: you constitute the irreplaceable and priceless treasure of the Church.

The history of Christianity confirms the value of your religious vocation: especially linked to you, down through the centuries, is the spread of the saving power of the Gospel among peoples and nations, on the European continent and then in the New World, in Africa and the Far East.

We wish to remember this especially this year, during which the assembly of the Synod of Bishops dedicated to consecrated life in the Church will be held. We must remember it in order to give glory to the Lord and to pray that such an important vocation, together with the vocation to family life, will not be stifled in any way in our time, nor even in the now approaching third millennium.

7. Today's Eucharistic Celebration brings together consecrated persons working in Rome, but in mind and heart we join with the members of Orders, Religious Congregations and Secular Institutes, scattered throughout the world, those especially who bear a special witness to Christ, paying for it with enormous sacrifices, not excluding at times martyrdom. With special affection I think of the men and women Religious present in the regions of the former Yugoslavia and in the other territories of the world, victims of an absurd fratricidal violence.

In greeting you, I also greet the other representatives of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, the Cardinal Prefect, the Secretary and all the collaborators. This is your common feast.

May Christ the light of the world be glorified in you, dear Sisters and Brothers! May Christ, the sign of contradiction for this world, be glorified. In him man lives: in him everyone becomes the glory of God, as St Irenaeus teaches (cf. St Irenaeus, Adversus haereses, 4, 20, 7). You are the epiphany of this truth. That is why you are so loved in the Church and why you spread great hope in humanity. Today, in a special way, we beseech the Lord that the evangelical leaven of your vocation may reach more and more hearts of young men and women and impel them to consecrate themselves unreservedly to the service of the Kingdom.

I say this thinking also of the others present who have come for the Wednesday General Audience. Certainly, many of them know consecrated persons, they realise the price of this personal consecration in the Church, they owe so much to the nuns, to the religious brothers who work in clinics, in schools, in the different environments of each people of the world, across the whole earth. I would like to invite these guests at our general audience today, dedicated to religious life, to pray for all the consecrated persons of the world, to pray for vocations. Perhaps this prayer will awaken some vocations in the hearts of young people.

8. Together with Mary and Joseph we go today on a spiritual pilgrimage to the temple in Jerusalem, the city of the great meeting. And with the Liturgy we say: "Arise, ye ancient doors . . .". Those who belong to the lineage of Abraham's faith find there a common point of reference. Everyone wants it to become a significant centre of peace, so that - according to the prophetic word of Revelation - God may wipe away every tear from the eyes of men there (cf. Rev 21:4), and that wall, which has remained over the centuries as a remnant of Solomon's ancient temple, may cease to be the "wall of weeping", and become a place of peace and reconciliation for believers in the one true God.

We make a pilgrimage to that city today, in a special way, we who have drawn our whole life's inspiration from the mystery of Christ: a life unreservedly dedicated to the Kingdom of God. Our pilgrimage culminates in communion with the Body and Blood, which the eternal Son of God took for Himself by becoming man, in order to present Himself to the Father, in the flesh of His humanity, as a perfect spiritual sacrifice, and thus fulfil the Covenant God made with Abraham, our father in faith, and brought to perfection in Christ (cf. Rom 4:16).

The Bishop of Rome looks with love towards Jerusalem, from where his first Predecessor, Peter, left one day and came to Rome driven by the apostolic vocation. After him also the Apostle Paul.

At the end of the second millennium, the Successor of Peter bends his knees to those places sanctified by the presence of the living God. Wandering around the world, through cities, countries, continents, he remains in communion with the divine light that shone there, in the truly holy land two thousand years ago to enlighten the nations and peoples of the whole world to enlighten us, beloved.

[Pope John Paul II, homily 2 February 1994]

In his arms, meeting the people. Ladder of God's condescension

Before our eyes we can picture Mother Mary as she walks, carrying the Baby Jesus in her arms. She brings him to the Temple; she presents him to the people; she brings him to meet his people.

The arms of Mother Mary are like the “ladder” on which the Son of God comes down to us, the ladder of God’s condescension. This is what we heard in the first reading, from the Letter to the Hebrews: Christ became “like his brothers and sisters in every respect, so that he might be a merciful and faithful high priest” (Heb 2:17). This is the twofold path taken by Jesus: he descended, he became like us, in order then to ascend with us to the Father, making us like himself.

In our heart we can contemplate this double movement by imagining the Gospel scene of Mary who enters the Temple holding the Child in her arms. The Mother walks, yet it is the Child who goes before her. She carries him, yet he is leading her along the path of the God who comes to us so that we might go to him.

Jesus walked the same path as we do, and shows us the new way, the “new and living way” (cf. Heb 10:20) which is he himself. For us, consecrated men and women, this is the one way which, concretely and without alternatives, we must continue to tread with joy and perseverance.

Fully five times the Gospel speaks to us of Mary and Joseph’s obedience to the “law of the Lord” (cf. Lk 2:22-24,27,39). Jesus came not to do his own will, but the will of the Father. This way – he tells us – was his “food” (cf. Jn 4:34). In the same way, all those who follow Jesus must set out on the path of obedience, imitating as it were the Lord’s “condescension” by humbling themselves and making their own the will of the Father, even to self-emptying and abasement (cf. Phil 2:7-8). For a religious, to advance on the path of obedience means to abase oneself in service, that is, to take the same path as Jesus, who “did not deem equality with God a thing to be grasped” (Phil 2:6). By emptying himself he made himself a servant in order to serve.

For us, as consecrated persons, this path takes the form of the rule, marked by the charism of the founder. For all of us, the essential rule remains the Gospel, yet the Holy Spirit, in his infinite creativity, also gives it expression in the various rules of the consecrated life which are born of the sequela Christi, and thus from this journey of abasing oneself by serving.

Through this “law” which is the rule, consecrated persons are able to attain wisdom, not something abstract, but a work and gift of the Holy Spirit. An evident sign of such wisdom is joy. The evangelical happiness of a religious is the fruit of self-abasement in union with Christ… And, when we are sad, we would do well to ask ourselves, “How are we living this kenosis?”

In the account of Jesus’ Presentation in the Temple, wisdom is represented by two elderly persons, Simeon and Anna: persons docile to the Holy Spirit, led by him, inspired by him. The Lord granted them wisdom as the fruit of a long journey along the path of obedience to his law, an obedience which likewise humbles and abases, but which also lifts up and protects hope, making them creative, for they are filled with the Holy Spirit. They even enact a kind of liturgy around the Child as he comes to the Temple. Simeon praises the Lord and Anna “proclaims” salvation (cf. Lk 2:28-32, 38). As with Mary, the elderly man holds the Child, but in fact it is the Child who guides the elderly man. The liturgy of First Vespers of today’s feast puts this clearly and beautifully: “senex puerum portabat, puer autem senem regebat”. Mary, the young mother, and Simeon, the kindly old man, hold the Child in their arms, yet it is the Child himself who guides them both.

Here it is not young people who are creative: the young, like Mary and Joseph, follow the law of the Lord, the path of obedience. The elderly, like Simeon and Anna, see in the Child the fulfilment of the Law and the promises of God. And they are able to celebrate: the are creative in joy and wisdom. And the Lord turns obedience into wisdom by the working of his Holy Spirit.

At times God can grant the gift of wisdom to a young person, but always as the fruit of obedience and docility to the Spirit. This obedience and docility is not something theoretical; it too is subject to the economy of the incarnation of the Word: docility and obedience to a founder, docility and obedience to a specific rule, docility and obedience to one’s superior, docility and obedience to the Church. It is always docility and obedience in the concrete.

In persevering along the path of obedience, personal and communal wisdom matures, and thus it also becomes possible to adapt rules to the times. For true “aggiornamento” is the fruit of wisdom forged in docility and obedience.

The strengthening and renewal of consecrated life are the result of great love for the rule, and also the ability to look to and heed the elders of one’s congregation. In this way, the “deposit”, the charism of each religious family, is preserved by obedience and by wisdom, working together. By means of this journey, we are preserved from living our consecration in “lightly”, in an unincarnate manner, as if it were some sort of gnosis which would ultimately reduce religious life to caricature, a caricature in which there is following without renunciation, prayer without encounter, fraternal life without communion, obedience without trust, and charity without transcendence.

Today we too, like Mary and Simeon, want to take Jesus into our arms, to bring him to his people. Surely we will be able to do so if we enter into the mystery in which Jesus himself is our guide. Let us bring others to Jesus, but let us also allow ourselves to be led by him. This is what we should be: guides who themselves are guided.

May the Lord, through the intercession of Mary our Mother, Saint Joseph and Saints Simeon and Anna, grant to all of us what we sought in today’s opening prayer: to “be presented [to him] fully renewed in spirit”. Amen.

[Pope Francis, Homily 2 February 2015]

Prologue. Logos: flesh

4th Advent Sunday (year A)

IV Sunday in Advent (year A) [21 December 2025]

May God bless us and the Virgin protect us! As we approach Christmas, the Word of God reminds us of the Lord's faithfulness even when the unfaithfulness of his people might weary him (first reading). The Gospel introduces us to Saint Joseph, the man who silently accepts and fulfils his mission as father of the Son of God.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (7:10-14)

It is around 735 BC. The kingdom of David has been divided into two states for two centuries: Samaria in the north and Jerusalem in the south, where Ahaz, a young king of twenty, reigns. The political situation is dramatic: the Assyrian empire, with its capital at Nineveh, dominates the region; the kings of Damascus and Samaria, already defeated by the Assyrians, now rebel and besiege Jerusalem to replace Ahaz with an allied ruler. The king panics: 'the heart of the king and the heart of the people were agitated like the trees of the forest by the wind' (Isaiah 7:2). The prophet Isaiah invites him to calm down and have faith: God has promised to keep David's dynasty alive; stability depends on trust in the Lord: if you do not believe, you will not remain steadfast. But Ahaz does not listen: he turns to idols and goes so far as to commit an atrocious act forbidden by the prophets, sacrificing his only son by passing him through the fire (cf. 2 Kings 16:3). He then decides to ask Assyria for help, a choice that entails the loss of political and religious independence. Isaiah strongly opposes this: it is a betrayal of the Covenant and of the liberation that began with Moses. In this context, Isaiah offers a sign: "Ask for a sign from the Lord your God." Ahaz responds hypocritically, pretending humility by not asking for it so as not to tempt the Lord, while he has already decided to entrust himself to Assyria. Isaiah replies rather harshly, saying not to weary 'my God', as if to indicate that Ahaz has now placed himself outside the Covenant. Despite the king's unfaithfulness, God remains faithful and, says Isaiah, 'the Lord himself will give you a sign': the young woman (the queen) is pregnant and the child will be called Immanuel, 'God with us'. This message from Isaiah is one of the classic texts of biblical messianism. Neither the enemies nor the king's sin can nullify the promise made by God to David. The child – probably the future king Hezekiah – will know how to choose good thanks to the Spirit of the Lord, and even before he grows up, the threat from Samaria and Damascus will disappear. In fact, shortly afterwards, the two kingdoms are destroyed by the Assyrians. Human freedom remains intact, and even Hezekiah will make mistakes; but Isaiah's prophecy affirms that nothing can prevent God's faithfulness to David's descendants. For this reason, throughout the centuries, Israel will wait for a king who will fully realise the name of Immanuel. The birth of the child is more than good news: it is an announcement of forgiveness. By sacrificing his son to the god Moloch, Ahaz compromised the promise made to David; but God does not withdraw his commitment. The birth of the new heir shows that God's faithfulness surpasses the unfaithfulness of men. The 'sign' thus takes on another encouraging messianic dimension, which we see more clearly in this Sunday's Gospel.

Important elements to remember: +Historical context: 735 BC, divided kingdom, threats from Syria, Samaria and Assyria. +Ahaz's panic and Isaiah's invitation to faith. +Serious unfaithfulness of the king: idolatry and sacrifice of his son. +Wrong political choice: alliance with Assyria. +Isaiah's sign: birth of the child called Immanuel. +Immediate fulfilment: destruction of Syria and Samaria by Assyria. +Central theme: the unfaithfulness of men does not nullify God's faithfulness. +Birth as an announcement of forgiveness and continuity of the Davidic promise.

Responsorial Psalm (23/24, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6)

The psalm takes us to the temple in Jerusalem: a great procession arrives at the gates and two choirs dialogue, asking: 'Who may ascend the mountain of the Lord? Who may stand in his holy place?' The image recalls Isaiah, who describes the thrice-holy God as a consuming fire before which no one could 'stand' without his help. The people of Israel have discovered that this totally 'Other' God also becomes the totally 'near' God, allowing man to remain in his presence. The psalm's answer is: 'Those who have clean hands and a pure heart, who do not turn to idols'. This is not primarily a matter of moralism, because the people know that they are admitted before God by grace, not by their own merit. Here, 'pure heart' means an undivided heart, turned solely to the one God; 'innocent hands' are hands that have not offered sacrifices to idols. The expression 'does not turn/literally does not lift up his soul' indicates not turning to empty deities: 'lifting up one's eyes' in the Bible means invoking, praying, recognising someone as God. This verse recalls the prophets' great struggle against idolatry. Isaiah had already opposed Ahaz in the eighth century; and even during the Exile in Babylon, the people - immersed in a polytheistic culture - were tempted to return to idols. The psalm, sung after the Exile, reminds us that the first condition of the Covenant is to remain faithful to the one God. Seeking the face of God is an image taken from the language of the court: only those who are faithful to the King can be admitted into his presence. Idols are defined as 'empty gods': Psalm 115 masterfully describes their nullity – they have eyes, mouths, hands, but they do not see, speak or act. Unlike these statues, God is alive and truly works. Fidelity to the one God is therefore the condition for receiving the blessing promised to the fathers and for entering into his plan of salvation. This is why Jesus will say: 'No one can serve two masters' (Matthew 6:24).

This fidelity, however, does not remain abstract: it concretely transforms life. The pure heart becomes a heart of flesh capable of eliminating hatred and violence; innocent hands become hands incapable of doing evil. The psalm says: "He will obtain blessing from the Lord, justice from God his salvation": this means both conforming to God's plan and living in right relationship with others. Here we already glimpse the light of the Beatitudes: Blessed are the pure of heart, for they will see God... blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice. The expression 'lift up your eyes', expressed here as 'those who do not turn to idols' (v. 4), returns in Zechariah and in the Gospel of John: 'They will look on the one they have pierced' (Jn 19:37), a sign of a new encounter with God.

Important elements to remember: +Scene in the temple with the dialogue of the choirs. +God is thrice holy and at the same time close: he allows man to 'stand' before him. +'Pure heart' and 'innocent hands' as fidelity to the one God, not idolatry and the prophets' constant struggle against idolatry (Ahaz, Exile). +Idols as 'empty gods'; criticism of Psalm 115. +Fidelity to the one God as the first condition of the Covenant, which has as its ethical consequences a righteous life, a renewed heart, and non-violent hands.

Second Reading from the Letter of St Paul to the Romans (1:1-7)

St Paul opens his letter to the Romans by summarising the whole Christian faith: the promises contained in the Scriptures, the mystery of Christ, his birth and resurrection, the free election of the holy people and the mission of the Apostles to the pagan nations. Writing to a community he has not yet met, Paul introduces himself with two titles: 'servant of Jesus Christ and apostle by calling', that is, sent, one who acts by mandate. He immediately attributes to Jesus the title of Christ, which means Messiah: to say 'Jesus Christ' is to profess that Jesus of Nazareth is the expected Messiah. Paul claims to have been 'chosen to proclaim the Gospel of God', the Good News: proclaiming the Gospel means proclaiming that God's plan is totally benevolent and that this plan is fulfilled in Jesus Christ. This Good News, says Paul, had already been promised in the prophets. Without the Old Testament, one cannot understand the New Testament because God's plan is unique, revealed progressively throughout history. The Resurrection of Christ is the centre of history, the heart of the divine plan from the beginning, as Paul also recalls in his letter to the Ephesians, where he speaks of God's will to recapitulate all things in Christ (Eph 1:9-10). 'According to the flesh': Jesus is a descendant of David, therefore a true man and Messiah. "According to the Spirit": Jesus is constituted Son of God "with power" through his Resurrection, and in the Resurrection God enthrones him as King of the new humanity. For Paul, this is the event that changes history because "if Christ has not been raised, then your faith is futile" (cf. 1 Cor 15:14). For this reason, he proclaims the Resurrection everywhere, so that "the name of Jesus Christ may be recognised", as he also writes in his letter to the Philippians (2:9-11), God has given him the Name above every other name, that of "Lord". Paul feels that his apostolic mission is "to bring about the obedience of faith in all peoples". "Obedience" is not servility, but trusting listening: it is the attitude of the child who trusts in the Father's love and welcomes his Word. Paul concludes with his typical greeting: 'Grace to you and peace from God', which is expressed in the priestly blessing in the Book of Numbers: grace and peace always come from God, but it is up to man to accept them freely.

Most important elements to remember: +Summary of the Christian faith: the promises are fulfilled in Christ, in the Resurrection, election and mission. +Paul's titles are servant and apostle, while the title 'Christ' is 'Messiah', which is a profession of faith. +The Gospel is God's merciful plan fulfilled in Christ. +Unity between the Old and New Testaments and Christ in his identity 'according to the flesh' and 'according to the Spirit': he is at the centre of God's plan from the beginning. +The Resurrection is the decisive event, and 'obedience of faith' is trusting listening. +Final blessing: grace and peace, in human freedom.

From the Gospel according to Matthew (1:18-24)

Matthew opens his Gospel with the expression: "Genealogy of Jesus Christ", that is, the book of the genesis of Jesus Christ, and presents a long genealogy that demonstrates Joseph's Davidic descent. Following the formula "A begot B", Matthew arrives at Joseph, but breaks with the pattern: he cannot say "Joseph begot Jesus"; instead, the evangelist writes: "Jacob begot Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called Christ" (Mt 1:16). This formula shows that the genealogy undergoes a change: for Jesus to be included in the line of David, his birth is not enough; Joseph must adopt him. The Son of God, in a certain sense, entrusts himself to the freedom of a man: the divine plan depends on Joseph's 'yes'. We are familiar with the Annunciation to Mary in Luke's Gospel, which is widely represented in art. Much less represented, however, is the Annunciation to Joseph, even though it is decisive: the human story of Jesus begins thanks to the free acceptance of a righteous man. The angel calls Joseph 'son of David' and reveals to him the mystery of Jesus' sonship: conceived by the Holy Spirit, yet recognised as his son. 'Do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife' means that Jesus will enter Joseph's house, and it will be he who will give him his name. Matthew also explains the meaning of the name Jesus: it means 'The Lord saves'. His mission is not only to free Israel from human power, but to save his people from sin. In Jewish tradition, the expectation of the Messiah included a total renewal: new creation, justice and peace. Matthew sees all this encapsulated in the name of Jesus. The text specifies: 'the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit'. There are two accounts of the virgin birth: this one by Matthew (Annunciation to Joseph) and the one by Luke (Annunciation to Mary). The Church professes this truth as an article of faith: Jesus is both true man, born of a woman, included in the lineage of David thanks to Joseph's free choice; and true Son of God, conceived by the Holy Spirit. Matthew links all this to Isaiah's prophecy: "The virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which means 'God-with-us'". The Greek translation of Isaiah (Septuagint), which Matthew quotes, uses the term 'virgin' (parthenos), while the Hebrew text uses almah, which means 'young woman' who is not yet married: even the ancient translation reflected the belief that the Messiah would be born of a virgin. Matthew insists: the child will be called Jesus (the Lord saves), but the prophet calls him Emmanuel (God-with-us). This is not a contradiction: at the end of Matthew's Gospel, Jesus will say, 'I am with you always, even unto the end of the world' (Mt 28:20). His name and his mission coincide: to save means to be with man, to accompany him, never to abandon him. Joseph believed and welcomed the presence of God. As Elizabeth said to Mary, 'Blessed is she who believed' (Lk 1:45), so we can say, 'Blessed is Joseph who believed: thanks to him, God was able to fulfil his plan of salvation'. Matthew uses the word "genesis" twice (Mt 1:1, 18), as in the book of Genesis when speaking of the descendants of Adam. This suggests that the entire history of humanity is recapitulated in Jesus: he is the New Adam, as St Paul will say.

Most important elements to remember: Break in the genealogy: Jesus is not "begotten" by Joseph but through adoption fulfils the plan of salvation. Joseph's freedom is fundamental in the fulfilment of God's plan. Title "son of David" and Joseph's legal role. Name of Jesus = "The Lord saves" mission of salvation from sins. +Virgin conception: mystery of faith, true man and true Son of God. +Quotation from Isaiah 7:14 according to the Greek translation ("virgin"). +Jesus and Emmanuel: salvation as the constant presence of God. +Parallel with Elizabeth's beatitude: Joseph's faith. +Jesus as the "New Adam" according to the reference to "Genesis".

Commentary by St Augustine, Sermon 51, on the Incarnation