don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Father and tried people

Our Father, who art in heaven . . .".

We stand at the altar around which the whole Church is gathered in Sarajevo. We utter the words that Christ, Son of the Living God, taught us: Son consubstantial with the Father. He alone calls God "Father" (Abba - Father! My Father!) and He alone can authorise us to address God by calling Him "Father", "Our Father". He teaches us this prayer in which everything is contained. We wish to find in this prayer today what we can and must say to God - our Father, at this moment in history, here in Sarajevo.

"Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name, thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven".

"I, the Bishop of Rome, the first Slavic Pope, kneel before You to cry out: "From plague, famine and war - deliver us!""

2. Our Father! Father of men: Father of peoples. Father of all peoples who dwell in the world. Father of the peoples of Europe. Of the peoples of the Balkans.

Father of the peoples who belong to the family of the South Slavs! Father of the peoples who have written their history here, on this peninsula, for centuries. Father of the peoples, touched unfortunately not for the first time by the cataclysm of war.

"Our Father . . .". I, Bishop of Rome, the first Slavic Pope, kneel before You to cry out: "From plague, famine and war - deliver us!" I know that in this plea many join me. Not only here in Sarajevo, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but in the whole of Europe and beyond. I come here carrying with me the certainty of this prayer uttered by the hearts and lips of countless of my brothers and sisters. For so long they have been waiting for this very "great prayer" of the Church, of the people of God, to be fulfilled in this place. For so long, I myself have invited everyone to join in this prayer.

How can we not recall here the prayer made in Assisi in January last year? And then the one raised in Rome, in St Peter's Basilica, in January of this year? From the beginning of the tragic events in the Balkans, in the countries of former Yugoslavia, the guiding thought of the Church, and in particular of the Apostolic See, has been the prayer for peace.

3. Our Father, "hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come . . .". May your holy and merciful name shine among men. Thy kingdom come, kingdom of justice and peace, of forgiveness and love.

"Thy will be done . . .".

Thy will be done in the world, and particularly in this troubled land of the Balkans. Thou lovest not violence and hatred. Thou shun injustice and selfishness. Thou wilt that men be brothers to one another and acknowledge Thee as their Father.

Our Father, Father of every human being, "Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven". Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven!

4. It is Christ "our peace" (Eph 2:14). He who taught us to address God by calling him "Father".

He who by His blood conquered the mystery of iniquity and division, and by His Cross broke down the massive wall that separated men, making them strangers to one another; He who reconciled humanity with God and united men among themselves as brothers.

That is why Christ was able to say one day to the Apostles, before his sacrifice on the Cross: 'I leave you peace, I give you my peace. Not as the world gives it, I give it to you" (John 14: 27). It is then that he promised the Spirit of Truth, who is at the same time Spirit of Love, Spirit of Peace!

Come, Holy Spirit! "Veni, creator Spiritus, mentes tuorum visita . . .!" "Come, Creator Spirit, visit our minds, fill with your grace the hearts you have created".

Come, Holy Spirit! We invoke you from this city of Sarajevo, crossroads of tensions between different cultures and nations, where the fuse was lit which, at the beginning of the century, triggered the First World War, and where, at the end of the second millennium, similar tensions are concentrated, capable of destroying peoples called by history to work together in harmonious coexistence.

Come, Spirit of peace! Through you we cry out: "Abba, Father" (Rom 8:15).

Give us this day our daily bread . . .".

Praying for bread means praying for all that is necessary for life. Let us pray that, in the distribution of resources among individuals and peoples, the principle of a universal sharing of mankind in God's created goods may always be realised.

Let us pray that the use of resources in armaments will not damage or even destroy the heritage of culture, which constitutes the highest good of humanity. Let us pray that restrictive measures, deemed necessary to curb the conflict, will not cause inhuman suffering to the defenceless population. Every man, every family has a right to its 'daily bread'.

6. "Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us . . .".

With these words we touch upon the crucial issue. Christ himself warned us of this, who, dying on the cross, said of his slayers: 'Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do' (Lk 23:34).

The history of men, peoples and nations is full of mutual resentment and injustice. How important was the historic expression addressed by the Polish Bishops to their German brethren at the end of the Second Vatican Council: 'Let us forgive and ask forgiveness'! If peace has been possible in that region of Europe, it seems to have come about thanks to the attitude effectively expressed by those words.

Today we want to pray for the renewal of a similar gesture: "Let us forgive and ask forgiveness" for our brothers in the Balkans! Without this attitude it is difficult to build peace. The spiral of 'guilt' and 'punishment' will never be closed, if at some point forgiveness is not achieved.

Forgiveness does not mean forgetting. If memory is the law of history, forgiveness is the power of God, the power of Christ acting in the affairs of men and peoples.

7. "Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil . . .".

Lead us not into temptation! What are the temptations that we ask the Father to remove today? They are those that make the heart of man a heart of stone, insensitive to the call of forgiveness and concord. They are the temptations of ethnic prejudices, which make one indifferent to the rights of others and their suffering. They are the temptations of exaggerated nationalisms, which lead to the overpowering of one's neighbour and the lust for revenge. They are all the temptations in which the civilisation of death expresses itself.

Faced with the desolating spectacle of human failures, let us pray with the words of Venerable Brother Bartholomew I, Patriarch of the Church of Constantinople: "Lord, make our hearts of stone crumble at the sight of your suffering and become hearts of flesh. Let your Cross dissolve our prejudices. With the vision of your agonising struggle against death, flee our indifference or our rebellion" (Way of the Cross at the Colosseum, Good Friday 1990, Opening Prayer).

Deliver us from evil! Here is another word that belongs completely to Christ and his Gospel. "I did not come to condemn the world, but to save the world" (Jn 12:47). Humanity is called to salvation in Christ and through Christ. To this salvation are also called the nations that the current war has so terribly divided!

Let us pray today for the saving power of the Cross to help overcome the historic temptation of hatred. Enough of the countless destructions! Let us pray - following the rhythm of the Lord's prayer - that the time of reconstruction, the time of peace, may begin.

Pray with us the dead of Sarajevo, whose remains lie in the nearby cemetery. They pray for all the victims of this cruel war, who in the light of God invoke reconciliation and peace for the survivors.

8. "Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God" (Mt 5:9). This is what Jesus told us in today's Gospel passage. Yes, dear Brothers and Sisters, we shall be truly blessed, if we make ourselves peacemakers of that peace that only Christ knows how to give (cf. Jn 14:27), indeed Christ himself. "Christ is our peace". We shall become peacemakers, if like him we are willing to forgive.

"Father, forgive them!" (Lk 23:34). Christ from the Cross offers forgiveness and also asks us to follow him on the arduous way of the Cross to obtain his peace. Only by accepting this invitation of his can we prevent selfishness, nationalism and violence from continuing to sow destruction and death.

Evil, in all its manifestations, constitutes a mystery of iniquity, in the face of which the voice of God, which we heard in the First Reading, rises up clear and decisive: "Thus speaks the High and Exalted . . . In high and holy place I dwell, but I am also with the oppressed and the humiliated" (Is 57:15). In these prophetic words is contained for all an invitation to a serious examination of conscience.

God is on the side of the oppressed: he is with the parents who mourn their murdered children, he listens to the helpless cry of the downtrodden, he is in solidarity with women humiliated by violence, he is close to refugees forced to leave their land and homes. He does not forget the suffering of families, the elderly, widows, young people and children. It is his people who are dying.

We must put an end to such barbarity! No more war! No more destructive fury! It is no longer possible to tolerate a situation that produces only fruits of death: killings, destroyed cities, ruined economies, hospitals lacking medicines, sick and elderly abandoned, families in tears and torn apart. A just peace must be achieved as soon as possible. Peace is possible if the priority of moral values over the claims of race or force is recognised.

9. Dear Brothers and Sisters! At this moment, together with you, I raise to the Lord the psalmist's cry: "Help us, God, our salvation, for the glory of your name, save us and forgive us our sins" (Ps 79:9).

Let us entrust this plea of ours to her who "stood" beneath the Cross silent and praying (cf. Jn 19:25). Let us look to the Blessed Virgin, whose Nativity the Church joyfully celebrates today.

It is significant that this visit of mine, long desired, has been able to take place on this Marian feast so dear to you. With Mary's birth there has blossomed in the world the hope of a new humanity no longer oppressed by selfishness, hatred, violence and the many other forms of sin that have stained the paths of history with blood. We ask Mary Most Holy that the day of full reconciliation and peace may also dawn for this land of yours.

Queen of peace, pray for us!

[Pope John Paul II, in connection with Sarajevo, 8 September 1994]

Abba

Continuing the catecheses on the ‘Lord’s Prayer’, today we shall begin with the observation that in the New Testament, the prayer seems to arrive at the essential, actually focusing on a single word: Abba, Father.

We have heard what Saint Paul writes in the Letter to the Romans: “you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the spirit of sonship. When we cry, ‘Abba, Father!’”(8:15). And the Apostle says to the Galatians: “And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Gal 4:6). The same invocation, in which all the novelty of the Gospel is condensed, recurs twice. After meeting Jesus and hearing his preaching, a Christian no longer considers God as a tyrant to be feared; he is no longer afraid but feels trust in Him expand in his heart: he can speak with the Creator by calling him ‘Father’. The expression is so important for Christians that it is often preserved intact, in its original form: ‘Abba’.

In the New Testament it is rare for Aramaic expressions to be translated into Greek. We have to imagine that the voice of Jesus himself has remained in these Aramaic words as if ‘recorded’: they have respected Jesus’ idiom. In the first words of the ‘Our Father’ we immediately find the radical newness of Christian prayer.

It does not simply use a symbol — in this case, the father figure — to connect to the mystery of God; it is instead about having, so to speak, Jesus’ entire world poured into one’s heart. If we do this, we can truly pray the ‘Our Father’. Saying ‘Abba’ is something much more intimate, more moving than simply calling God ‘Father’. This is why someone has proposed translating this original Aramaic word ‘Abba’ with ‘Dad’ or ‘Papa’. Instead of saying ‘our Father’, saying ‘Dad, Papa’. We shall continue to say ‘our Father’ but with the heart we are invited to say ‘Dad’, to have a relationship with God like that of a child with his dad, who says ‘dad’ and says ‘papa’. Indeed, these expressions evoke affection, they evoke warmth, something that casts us into the context of childhood: the image of a child completely enveloped in the embrace of a father who feels infinite tenderness for him. And for this reason, dear brothers and sisters, in order to pray properly, one must come to have a child’s heart. Not a self-sufficient heart: one cannot pray properly this way. Like a child in the arms of his father, of his dad, of his papa.

But of course the Gospels better explain the meaning of this word. What does this word mean to Jesus? The ‘Our Father’ takes on meaning and colour if we learn to pray it after having read, for example, the Parable of the Merciful Father, in Chapter 15 of Luke (cf. Lk 15:11-32). Let us imagine this prayer recited by the prodigal son, after having experienced the embrace of his father who had long awaited him, a father who does not remember the offensive words the son had said to him, a father who now simply makes him understand how much he has been missed. Thus we discover how those words become vibrant, receive strength. And let us ask ourselves: is it possible that You, O God, really know only love? Do you not know hatred? No — God would respond — I know only love.

Where in You is vengeance, the demand for justice, anger at your wounded honour? And God would respond: I know only love.

In that parable the father’s manner of conduct somehow recalls the spirit of a mother. It is especially mothers who excuse their children, who protect them, who do not suspend empathy for them, who continue to love them, even when they would no longer deserve anything.

It is enough to evoke this single expression — Abba — for Christian prayer to develop. And in his Letters, Saint Paul follows this same path, because it is the path taught by Jesus: in this invocation there is a force that draws all the rest of the prayer.

God seeks you, even if you do not seek him. God loves you, even if you have forgotten about him. God glimpses beauty in you, even if you think you have squandered all your talents in vain. God is not only a father; he is like a mother who never stops loving her little child. On the other hand, there is a ‘gestation’ that lasts forever, well beyond the nine months of the physical one; it is a gestation that engenders an infinite cycle of love.

For a Christian, praying is simply saying ‘Abba’; it is saying ‘Dad’, saying ‘Papa’, saying ‘Father’ but with a child’s trust.

It may be that we too happen to walk on paths far from God, as happened to the prodigal son; or to sink into a loneliness that makes us feel abandoned in the world; or, even to make mistakes and be paralyzed by a sense of guilt. In those difficult moments, we can still find the strength to pray, to begin again with the word ‘Abba’, but said with the tender feeling of a child: ‘Abba’, ‘Dad’. He does not hide his face from us. Remember well: perhaps one has bad things within, things he does not know how to resolve, much bitterness for having done this and that.... He does not hide His face. He does not close himself off in silence. Say ‘Father’ to Him and He will answer you. You have a father. ‘Yes, but I am a delinquent...’. But you have a father who loves you! Say ‘Father’ to him, start to pray in this way, and in the silence he will tell us that he has never lost sight of us. ‘But Father, I have done this...’. — ‘I have never lost sight of you; I have seen everything. But I have always been there, close to you, faithful to my love for you’. That will be his answer. Never forget to say ‘Father’. Thank you.

[Pope Francis, General Audience 16 January 2019]

Judgment and sentences

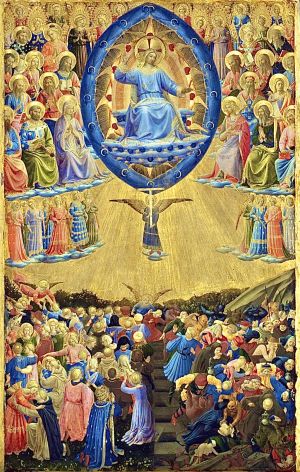

(Mt 25:31-46)

The famous Judgment passage presents the ‘coming’ Risen (v.31) as «Son of man», that is, authentic and complete development of divine plan for humanity: his kind of "verdict" follows.

God embraces the limited condition of his creatures, so the behavior that realizes our life does not concern the religious attitude itself, but what we have had towards our fellow men.

In all ancient beliefs, the soul of the deceased was weighed on a notarial basis and judged according to the positive or negative balance.

In the opinion of the rabbis, Divine Mercy intervened in favor only when the good and bad works were balanced.

Jesus does not speak of a Court that proclaims immutable negative sentences on the whole person, but of his humanizing traits.

«Life of the Eternal» (v.46 Greek text) alludes to a kind of life that is not biological but relational and full of being, which we can already experience.

These are episodes in which our genuine DNA emerged, the Gold that inhabits us: when we knew how to respond to the needs not of God, but of life itself and of our brothers.

These are the moments in which we have been profound listeners to the nature, hope and vocation of all - sensitive to the needs of others. Opportunities that have allowed us to bring the human condition closer to the heavenly one.

Comparing the ‘works’ declared "paradigm" with those of the lists of other religions - even in ancient Egypt - we note the difference in v.36: «I was in prison and you came to me» (vv.39.43).

The difference is remarkable precisely under the criterion of divine Justice: it overlooks forensic considerations, because it creates justice where there is none.

The Father gives life in every case, because He is not “good” [as is believed in all devout persuasions] but exclusively good.

‘Righteous’ - then - did not even realize that they had done who knows what: they spontaneously corresponded to their nature as sons (v.39).

They have had sympathy for our ‘flesh’ in its reality - considering it familiar. They have loved with and like Jesus, in Him.

The others, all taken up by formalisms of no interest to God, are surprised that the Father is not all there where they had imagined Him - locked in the sentences of ordinary justice: «When we saw you [...] in prison and did not we serve you?» (v. 44).

Vocation to meet leads spontaneously to transgress divisions: legalistic, of retribution, or prejudice and kind of cult.

This is the eminent Salvation - which nestles in the direct and genuine aspect, not so much in the organized purposes; nor does it have any consistency on the basis of opinions.

We fulfill ourselves in responding to the instinctive Call that arises from our own essential (altruistic) imprint, even the slightest, ill-considered, or eccentric and shaky - not extraordinary.

Without too external conditions, it recognizes itself disseminated in the soul and in the beneficial divinizing fullness of the «Son of man».

Jesus' ultimate Teaching: eminent, global and all-human Judgement; not verdict by concept and account.

Here the Jesus’ identification with the little ones: his Person has a central meaning, which surpasses the ‘distinction’ between friends and outlaws.

The Person is now a different Subject, far richer - solid in itself, but expanding into the divine and human You, even destitute.

[Monday 1st wk. in Lent, February 23, 2026]

Judgement vs sentences

(Mt 25:31-46)

The famous Judgment passage presents the Risen One coming (v.31) as the "Son of Man", that is, the authentic and complete development of the divine plan for humanity: his kind of "verdict" follows.

God embraces the condition of limitation of his creatures, so the behaviour that fulfils our life is not about our religious attitude per se, but about our attitude towards our fellow human beings.

This is the evangelical call of the recent encyclical [October 2020] on fraternity and social friendship.

Aware of the situation, the Magisterium is now becoming the sting of every obvious and unimportant group spirituality, of every folklore mysticism, of every hollow, intimist, still sitting on the fence.... empty, intimist, still sitting in bedside armour.

In all ancient beliefs, the soul of the deceased was weighed on a notarial basis and judged according to its positive or negative balance.

According to the rabbis, divine mercy intervened in favour, only when good and bad deeds were balanced out.

Jesus does not speak of a tribunal that proclaims unchangeable negative judgements on the whole person, but of the traits of complete existence that - being in themselves indestructible because they are humanising - are saved and assumed, introduced into definitive existence.

"Life of the Eternal" (v.46 Greek text) alludes to a non-biological but relational kind of life and completeness of being, which we can already experience.

These are episodes in which our divine DNA, the Gold that inhabits us, has surfaced: when we have been able to respond to the needs not of God, but of life itself and of our brothers and sisters.

These are the moments when we have been deep listeners to nature, to the hope and vocation of all - sensitive to the needs of others.

Opportunities that have allowed us to bring the human condition closer to the heavenly one.

Comparing the "works" declared as "paradigm" with those in the lists of classical Judaism (Is 58:6-7) and other religions - even ancient Egypt [Book of the Dead, c.125] - we note the difference in v.36: "I was in prison and you came to me" (cf. vv.39.43).

The difference is remarkable precisely under the criterion of divine justice: it overrides forensic considerations, because it creates justice where there is none.

The Father lays down life in every case, because he is not good as is believed in all devout persuasions, but exclusively good.

The 'righteous' - then - did not even realise that they had done who knows what: they spontaneously corresponded to their innate and transparent nature as sons (v.39).

They have had sympathy for the "flesh" in the reality in which it is found - and where it is found - valuing it as family. They have loved with and like Jesus, in Him.

They have not loved for Jesus - as if the other's condition could be bracketed, and underneath considered a nuisance on which to build a fiction, albeit a sympathetic one.

The other observant people, on the other hand, all caught up in formalisms of ritual, doctrine and discipline that God does not care about, are surprised that the Father is not all there where they had imagined Him to be.

That is, respectable but empty and stagnant like them, caught up in the sentences of ordinary justice: "When did we see you [...] in prison and did not serve you?" (v.44).

The vocation to meet leads us spontaneously to transgress divisions: legalistic, of retribution, or prejudices, and gender of worship.

This is the eminent, weighty Salvation - lurking in the direct and genuine. Not so much in organised intentions; nor does it have any consistency on the basis of opinion.

We fulfil ourselves in responding to the instinctive call that arises from our own essential altruistic imprint: even minimal, ill-considered, or eccentric, shaky and unfulfilling - not extraordinary.

Without excessively external conditions, it is recognised to be disseminated in the soul and in the beneficial, divinising fullness of the 'Son of Man'.

Jesus' ultimate teaching: Distinguished, global and all-human judgement.

Not qualunquist or contraband response, to concept and account.

Jesus' identification with the little ones remains singular: "what you have done even to one of these brothers of mine, the least of these, you have done to me" (v.40).

Otherwise: "not even to me have you done" (v.45).

His Person has a central meaning, without distinction between friends and counter-legislators, between pious doers and non-doers.

Adherence to Christ is not judged on the basis of works far removed from the humanising Core.

Beautiful things that can also be accomplished without a spirit of benevolence [out of duty and culture, or even lustre and calculation] - but on love.

God is not obliged to reward merit.

Good works can also be displayed or performed against the Father: as if to bind his hands.

This is a typical misrepresentation of religions, which provide rewards for the pious.

Misunderstanding foreign to the experience of Faith, whose only security lies in the risk of exploration, growth, and the quality of relationships - indeed, humanising relationships.

Life and death are quite distinct ['right and left': proverbially, fortune and misfortune] according to the characteristics of authentic piety towards God Himself... because His honour is reflected in the promotion of woman and man, caught in their concrete situation.

The only non-negotiable principle is service to the good of each person.

Works of love are an expression of true Communion with Christ - in this way freed from cerebral tares and mannerisms: from any kind of limitation or judgement that conditions their value.

In short, there is no need to do targeted and extraordinary, or mechanical things, but to let God act - respecting and valuing the brother for what he is.

Even outside the visible realm of the kingdom of the apostles (or a doctrine-discipline) there is authentic 'Christianity': civilisation of children.

In short, no predestination to the condemnation of the distant or errant and imperfect, except for a lack of fraternity that retrieves the impossible - even 'counter-law'.

Authentic Kingship of Christ and His own.

In Palestine, in the evening, shepherds used to separate the sheep from the goats that needed shelter from the cold.

In order to emphasise its importance, the question raised by the evangelist adopts the colourful forms of rabbinic preaching.

The question is not who is saved and who is not.

If anything, the question is: on which occasions are we willingly out in the open even at 'night', and humanise - and on which do we behave in a more belligerent, closed manner, but without becoming... lambs?

In Christ, the victory over selfishness loses its meaning of annihilation of the possibilities of individual growth - which is not achieved by stubbornness.

His power is anything but stagnant and divisive. It does not conceal the capabilities we do not see, or what we do not know.

Opposite situations are the glorious moments of the same victory. This is evident in the continuation of the passage, which proclaims the other extreme of love: "the Son of Man is delivered up to be crucified" (Mt 26:2).

Thus, the purpose of Mt is not to describe the end of the world, but to provide guidance on how to live wisely [today] in order to form a family and not to be fascinated by the immediate glitter of false jewels - even well-prepared ones.

The Recall of the Gospels insists on contrasting this with a frivolous spirituality: the only appropriate distinction.

The man of God does not satisfy the lusts of even ecclesiastical careers, and every whim.

The Tao Tê Ching (iii) suggests, addressing even the wise ruler: 'Do not exalt the most capable, do not let the people contend; do not covet the goods that are difficult to obtain, do not let the people become thieves; do not obtain what you may covet, do not let the people's heart be troubled.

Commented Master Wang Pi: "When you exalt the most capable, you give prestige to their name; the glory goes beyond their office, and they are always binge-watching, comparing their abilities. When goods are prized beyond their usefulness, the greedy rush upon them, haggling; they drill walls, break into coffers, and become thieves at the risk of their lives'.

And Master Ho-shang Kung adds, about "those whom the world judges to be excellent": "With their specious talk, they adapt themselves to the circumstances, distancing themselves from the Tao; they stick to form, rejecting substance.

The Lord's Appeal emphasises the qualitative aspects, of Person in relation: He illustrates how life is worth betting on.

This is so that all may experience fullness of being - which is not the result of opportunism.

Nor is it the result of belonging: all discrimination between 'called' in the visible Church and those far from it is suspended.

The strong images of the Gospel passage serve to make us reflect, to open our eyes, to shift the horizon, to impress on our conscience what is worth putting into play: everything, about the choices to be made.

Genuine love that moves heaven and earth is that which succeeds in making the wicked right - in the free Gift, free of conditions and forms of self-love. Even exempt from sacred evaluations.

Intuates the Tao (xxxiii): "Who does these things? Heaven and Earth [...] Those who give themselves to the Tao identify with the Tao.

The genuine arises and flourishes from the disinterested and spontaneous way, without any effort or contrived purpose.

Here man is a different Subject, far richer - firm in himself, but expanding into the divine and human You, even destitute.

"In today's Gospel page, Jesus identifies himself not only with the shepherd-king, but also with the lost sheep. We could speak of a "double identity": the king-shepherd, Jesus, also identifies himself with the sheep, that is, with the smallest and neediest brothers and sisters. And he thus indicates the criterion of the judgement: it will be taken on the basis of the concrete love given or denied to these people [...] Therefore, the Lord, at the end of the world, will review his flock, and he will do so not only on the side of the shepherd, but also on the side of the sheep, with whom he has identified himself. And he will ask: "Have you been a little shepherd like me?" [...] And we only go home with this sentence: "I was there. Thank you!" or: "You forgot about me"'".

(Pope Francis)

It marked Christian culture

Today's Gospel insists precisely on the universal kingship of Christ the Judge, with the stupendous parable of the Last Judgment, which St Matthew placed immediately before the Passion narrative (25: 31-46). The images are simple, the language is popular, but the message is extremely important: it is the truth about our ultimate destiny and about the criterion by which we will be evaluated. "I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me" (Mt 25: 35) and so forth. Who does not know this passage? It is part of our civilization. It has marked the history of the peoples of Christian culture: the hierarchy of values, the institutions, the multiple charitable and social organizations. In fact, the Kingdom of Christ is not of this world, but it brings to fulfilment all the good that, thank God, exists in man and in history. If we put love for our neighbour into practice in accordance with the Gospel message, we make room for God's dominion and his Kingdom is actualized among us. If, instead, each one thinks only of his or her own interests, the world can only go to ruin.

Dear friends, the Kingdom of God is not a matter of honours and appearances but, as St Paul writes, it is "righteousness and peace, and joy in the Holy Spirit" (Rm 14: 17). The Lord has our good at heart, that is, that every person should have life, and that especially the "least" of his children may have access to the banquet he has prepared for all. Thus he has no use for the forms of hypocrisy of those who say: "Lord, Lord" and then neglect his commandments (cf. Mt 7: 21). In his eternal Kingdom, God welcomes those who strive day after day to put his Word into practice. For this reason the Virgin Mary, the humblest of all creatures, is the greatest in his eyes and sits as Queen at the right of Christ the King. Let us once again entrust ourselves to her heavenly intercession with filial trust, to be able to carry out our Christian mission in the world.

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 23 November 2008]

Idea of Heaven in relation to the Paschal Mystery of Christ

“Heaven" as the fullness of intimacy with God

Reading: 1 Jn 3:2-3

1. When the form of this world has passed away, those who have welcomed God into their lives and have sincerely opened themselves to his love, at least at the moment of death, will enjoy that fullness of communion with God which is the goal of human life.

As the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches, “this perfect life with the Most Holy Trinity — this communion of life and love with the Trinity, with the Virgin Mary, the angels and all the blessed — is called ‘heaven’. Heaven is the ultimate end and fulfilment of the deepest human longings, the state of supreme, definitive happiness” (n. 1024).

Today we will try to understand the biblical meaning of “heaven”, in order to have a better understanding of the reality to which this expression refers.

2. In biblical language “heaven”, when it is joined to the “earth”, indicates part of the universe. Scripture says about creation: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Gn 1:1).

Metaphorically speaking, heaven is understood as the dwelling-place of God, who is thus distinguished from human beings (cf. Ps 104:2f.; 115:16; Is 66:1). He sees and judges from the heights of heaven (cf. Ps 113:4-9) and comes down when he is called upon (cf. Ps 18:9, 10; 144:5). However the biblical metaphor makes it clear that God does not identify himself with heaven, nor can he be contained in it (cf. 1 Kgs 8:27); and this is true, even though in some passages of the First Book of the Maccabees “Heaven” is simply one of God's names (1 Mc 3:18, 19, 50, 60; 4:24, 55).

The depiction of heaven as the transcendent dwelling-place of the living God is joined with that of the place to which believers, through grace, can also ascend, as we see in the Old Testament accounts of Enoch (cf. Gn 5:24) and Elijah (cf. 2 Kgs 2:11). Thus heaven becomes an image of life in God. In this sense Jesus speaks of a “reward in heaven” (Mt 5:12) and urges people to “lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven” (ibid., 6:20; cf. 19:21).

3. The New Testament amplifies the idea of heaven in relation to the mystery of Christ. To show that the Redeemer's sacrifice acquires perfect and definitive value, the Letter to the Hebrews says that Jesus “passed through the heavens” (Heb 4:14), and “entered, not into a sanctuary made with hands, a copy of the true one, but into heaven itself” (ibid., 9:24). Since believers are loved in a special way by the Father, they are raised with Christ and made citizens of heaven. It is worthwhile listening to what the Apostle Paul tells us about this in a very powerful text: “God, who is rich in mercy, out of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead through our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ (by grace you have been saved), and raised us up with him, and made us sit with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus, that in the coming ages he might show the immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus” (Eph 2:4-7). The fatherhood of God, who is rich in mercy, is experienced by creatures through the love of God's crucified and risen Son, who sits in heaven on the right hand of the Father as Lord.

4. After the course of our earthly life, participation in complete intimacy with the Father thus comes through our insertion into Christ's paschal mystery. St Paul emphasizes our meeting with Christ in heaven at the end of time with a vivid spatial image: “Then we who are alive, who are left, shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air; and so we shall always be with the Lord. Therefore comfort one another with these words” (1 Thes 4:17-18).

In the context of Revelation, we know that the “heaven” or “happiness” in which we will find ourselves is neither an abstraction nor a physical place in the clouds, but a living, personal relationship with the Holy Trinity. It is our meeting with the Father which takes place in the risen Christ through the communion of the Holy Spirit.

It is always necessary to maintain a certain restraint in describing these “ultimate realities” since their depiction is always unsatisfactory. Today, personalist language is better suited to describing the state of happiness and peace we will enjoy in our definitive communion with God.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church sums up the Church's teaching on this truth: “By his death and Resurrection, Jesus Christ has ‘opened’ heaven to us. The life of the blessed consists in the full and perfect possession of the fruits of the redemption accomplished by Christ. He makes partners in his heavenly glorification those who have believed in him and remained faithful to his will. Heaven is the blessed community of all who are perfectly incorporated into Christ” (n. 1026).

5. This final state, however, can be anticipated in some way today in sacramental life, whose centre is the Eucharist, and in the gift of self through fraternal charity. If we are able to enjoy properly the good things that the Lord showers upon us every day, we will already have begun to experience that joy and peace which one day will be completely ours. We know that on this earth everything is subject to limits, but the thought of the “ultimate” realities helps us to live better the “penultimate” realities. We know that as we pass through this world we are called to seek “the things that are above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of God” (Col 3:1), in order to be with him in the eschatological fulfilment, when the Spirit will fully reconcile with the Father “all things, whether on earth or in heaven” (Col 1:20).

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 21 July 1999]

Christian paradox, which comes to us every day

But the Christian paradox is that the Judge is not vested in the fearful trappings of royalty, but is the shepherd filled with meekness and mercy.

In fact, in this parable of the final judgement, Jesus uses the image of a shepherd, recalling images of the prophet Ezekiel who had spoken of God’s intervention in favour of his people against the evil shepherds of Israel (cf. 34:1-10). They had been cruel exploiters, preferring to feed themselves rather than the flock; therefore, God himself promises to personally take care of his flock, defending it from injustice and abuse. This promise God made to his people is fully accomplished in Jesus Christ, the Shepherd. He is indeed the Good Shepherd. He too says of himself: “I am the good shepherd” (Jn 10:11, 14).

In today’s Gospel passage, Jesus identifies himself not only with the king-shepherd, but also with the lost sheep, we can speak of a “double identity”: the king-shepherd, Jesus identifies also with the sheep: that is, with the least and most needy of his brothers and sisters. And he thus indicates the criterion of the judgement: it will be made on the basis of concrete love given or denied to these persons, because he himself, the judge, is present in each one of them. He is the judge. He is God-Man, but he is also the poor one. He is hidden and present in the person of the poor people that he mentions right there. Jesus says: “Truly, I say to you, as you did it (or did it not) to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it (you did it not) to me” (cf. vv. 40, 45). We will be judged on love. The judgement will be on love, not on feelings, no: we will be judged on works, on compassion that becomes nearness and kind help. Do I draw near to Jesus present in the persons of the sick, the poor, the suffering, the imprisoned, of those who hunger and thirst for justice? Do I draw near to Jesus present there? This is the question for today.

Therefore, at the end of the world, the Lord will inspect the flock, and he will do so not only from the perspective of the shepherd, but also from the perspective of the sheep, with whom he has identified. And he will ask us: “Were you a little bit like a shepherd as myself?” “Were you a shepherd to me who was present in those people who were in need, or were you indifferent?”. Brothers and sisters, let us look at the logic of indifference, of those who come to mind immediately. Looking away when we see a problem. Let us remember the parable of the Good Samaritan. That poor man, wounded by the brigands, thrown to the ground, between life and death, was there alone. A priest passed by, saw, and went on his way. He looked the other way. A Levite passed by, saw and looked the other way. Before my brothers and sisters in need, am I indifferent like this priest, like this Levite and look the other way? I will be judged on this: on how I drew near, how I looked on Jesus present in those in need. This is the logic, and it is not I who is saying this: Jesus says it. “What you did to that person and that person and that person, you did it to me. And what you did not do to that person and that person and that person, you did not do it to me, because I was there”. May Jesus teach us this logic, this logic of being close, of drawing near to him, with love, in the person who is suffering most.

Let us ask the Virgin Mary to teach us to reign by serving. Our Lady, assumed into Heaven, received the royal crown from her son because she followed him faithfully — she is the first disciple — on the way of Love. Let us learn from her to enter God’s Kingdom as of now through the door of humble and generous service. And let us return home only with this phrase: “I was present there. Thank you!”. Or: “You forgot about me”.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 22 November 2020].

But he comes to us every day

The Gospel passage opens with a grandiose vision. Jesus, addressing his disciples, says: “When the Son of man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on his glorious throne” (Mt 25:31). It is a solemn introduction to the narrative of the Last Judgment. After having lived his earthly existence in humility and poverty, Jesus now shows himself in the divine glory that pertains to him, surrounded by hosts of angels. All of humanity is summoned before him and he exercises his authority, separating one from another, as the shepherd separates the sheep from the goats.

To those whom he has placed at his right he says: “Come, O blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me” (vv. 34-36). The righteous are taken aback, because they do not recall ever having met Jesus, much less having helped him in that way, but he declares: “as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me” (v. 40). These words never cease to move us, because they reveal the extent to which God’s love goes: up to the point of taking flesh, but not when we are well, when we are healthy and happy, no; but when we are in need. And in this hidden way he allows himself to be encountered; he reaches out his hand to us as a mendicant. In this way Jesus reveals the decisive criterion of his judgment, namely, concrete love for a neighbour in difficulty. And in this way the power of love, the kingship of God is revealed: in solidarity with those who suffer in order to engender everywhere compassion and works of mercy.

The Parable of the Judgment continues, presenting the King who shuns those who, during their lives, did not concern themselves with the needs of their brethren. Those in this case too are surprised and ask: “Lord, when did we see thee hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison, and did not minister to thee?” (v. 44). Implying: “Had we seen you, surely we would have helped you!”. But the King will respond: “as you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me” (v. 45). At the end of our life we will be judged on love, that is, on our concrete commitment to love and serve Jesus in our littlest and neediest brothers and sisters. That mendicant, that needy person who reaches out his hand is Jesus; that sick person whom I must visit is Jesus; that inmate is Jesus, that hungry person is Jesus. Let us consider this.

Jesus will come at the end of time to judge all nations, but he comes to us each day, in many ways, and asks us to welcome him. May the Virgin Mary help us to encounter him and receive him in his Word and in the Eucharist, and at the same time in brothers and sisters who suffer from hunger, disease, oppression, injustice. May our hearts welcome him in the present of our life, so that we may be welcomed by him into the eternity of his Kingdom of light and peace.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 26 November 2017]

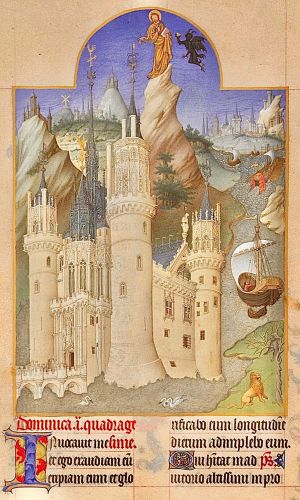

Lenten Spirituality, and the enemy who looks like a friend

Faith, Temptations: our success

(Mt 4:1-11 Mc 1:12-15 Lc 4:1-13)

Only the man of God is tempted.

In the Bible, temptation is not a kind of danger or seduction for death, but an opportunity for life.

Even more: a relaunch from the usual laces.

When existence runs off without jolts, here is instead the ‘earthquake of flattery’... a trial that puts back in the balance.

Lenten spirituality.

In God's plan, the test of Faith doesn’t come to destroy minds and life, but to disturb the swampy reality of obligations contracted in the quiet of conformist etiquette.

In fact, in the labels we are not ourselves, but a role: here it’s impossible to seriously conform to Christ.

Every danger comes for a healthy jolt, of image too - and to move us.

The exodus stimulates us to take a leap forward; not to bury existence in the anthology of uncritical mechanisms under conditions.

The passage is narrow and it’s also obligatory; hurts. But it spurs so that we can meet again ourselves, our brothers and the world.

Providence presses: it’s educating us to look both every detail and the fundamental option in face.

To get out of dangers, ‘seductions’ or disturbances, we are obliged to look inside and bring out all the resources, even those unknown (or to which we have not granted credit).

The difficulty and the crisis force us to find solutions, give space to the neglected and shaded sides; see well, ask for help; get informed, enter into a qualitative relationship and compare ourselves.

Of necessity, virtue: after attraction and enticement or trial, the renewed point of view, reaffirmed by a new evaluation, questions the soul about the calibre of choices and our own infirmities.

Unsteady situations themselves have something to tell us: they come from the deepest layers of being, which we must encounter - and they take the form of mouldable energies, to invest.

The Calls to revolutionize opinions of oneself and of things - vocations to a ‘new birth’ - are not incitements for the worst, nor spiritual humiliations.

The "crosses" and even the dazzles are a territory of pain that leads to intimate contact with our Source, which re-arouses us from time to time.

The man who is always listening to his own Core and remains faithful to the singular dignity and uniqueness of the Mission, however, must bear the pressures of a kind of evil that only instigates death.

Mt and Lk describe these (‘apparently friendly’, for success) enticements in three symbolic pictures:

the relationship with things [turning stones into bread]; with others [temptation of kingdoms]; with God [Trust in the Father's Action].

In the Holy Scriptures a curious fact emerges: spiritually weak people are never tempted! And the other way around is also true.

It’s the way of living and internalizing the lightning bolt or the time of Temptation that distinguishes Faith from the banality of devotion any.

[1st Sunday in Lent, February 22, 2026]

Lenten Spirituality, and the enemy who seems a friend

Faith, Temptations: our success

(Mt 4:1-11; Mk 1:12-15; Lk 4:1-13)

Only the man of God is tempted.

In the Bible, temptation is not a kind of danger or seduction to death, but an opportunity for life. Even more: a revival from the usual entanglements.

Optics of Lenten Spirituality:

Every day we verify that a relevant pitfall for the experience of Faith seems to be 'luck'. It binds us to the immediate good of individual situations.

Vice versa, on the other hand, makes routine: here is well-being, escaping from failures and unhappy events, the stasis of the same-as-before.

A devout person can even use religion to sacralise his or her coarse world, bound by habits (considered stable).

So - according to circumstance - even willingly enter into the practice of the sacraments, as long as they remain parentheses that do not mean much.

When existence runs smoothly, here instead is the earthquake of flattery... a challenge that throws one back into the balance.

In God's plan, the test of Faith does not come to destroy minds and existence, but to disturb the swampy reality of obligations contracted in the quiet of conformist etiquette.

In fact, in labels we are not ourselves, but a role: here it is impossible to truly conform to Christ.

Every peril comes for a salutary jolt even of image, and to shake us up.

The Exodus encourages us to take a leap forward - not to drown our existence in the anthology of uncritical mechanisms under conditions, and to submit to the influence of recognised cords; 'useful', but diverting our naturalness.

The passage is narrow and even forced; it wounds. But it spurs us on to meet ourselves, our brothers, and the world again.

Providence presses on: it is educating us to look in the face both every detail and the fundamental option.

We do not grow or mature by settling our souls on everyone's opinions and sitting in majority, habitual, 'respectable', supposedly truthful situations. Yet not very spontaneous, lacking transparency and reciprocity with our founding Eros.

Nor do we become adults by embracing ascetic athleticism, or easier shortcuts of mass, class, cliques, or herd - which make us outsiders.

To emerge from dangers, seductions, disturbances, we are obliged to look within and bring out all resources, even those unknown or to which we have not given credit.

Difficulties and crises force us to find solutions, to give space to the neglected, shadowed sides; to see well and ask for help; to inform ourselves, to enter into a qualitative relationship, and to confront ourselves from within.

Of necessity, virtue: after the attraction and the enticement or the trial, the renewed and reaffirmed point of view from a new evaluation questions the soul about the calibre of choices - about our own infirmities.

They themselves have something to tell us: they come from the deepest layers of being, which we must encounter - in order not to remain disassociated. And they take the form of mouldable energies, then to be invested in.

The calls to revolutionise views of self and of things - the vocations to a new birth - are not incitements to annihilate one's world of relationships, or spurs to the worst, nor spiritual humiliation.

The 'crosses' and even the blunders are a territory of labour pains that guide one to intimate contact with our Source - which from time to time re-awakens us with new genesis, with different births.

The man who always listens to his own centre and remains faithful to the singular dignity and uniqueness of Mission, must however withstand the pressures of an evil that only instigates death.

Mt and Lk describe such seemingly friendly allurements, i.e. for success, in three symbolic pictures:

Here is the relationship with things [stones into bread]; with others [temptation of kingdoms]; with God [on Trust in the Father's Action].

Stones into bread: the Lord's own life tells us that it is better to be defeated than to be well off.

The elusive way - even pious, inert, without direct contact - of relating to material realities is under indictment.

The person, even religious but empty, merely gives or receives directions, or allures with special effects.

He makes use of prestige and his own qualities and titles, almost as if to escape the difficulties that may bother him, involve him at root.

In contrast, the person of Faith is not only empathetic and supportive in form, but fraternal and authentic.

He does not keep a safe distance from problems, nor from what he does not know; he takes Exodus seriously. Paying it.

He feels the impulse to walk the hard path side by side with himself (in deep truth) and with others, without calculation or privilege.

Nor does it deploy resources solely in its own favour - by detaching and retreating, or by making do; by blundering, by conforming to the club of conformists from the relaxation zone and fake security.

Temptation of kingdoms. Our] counterpart is not exaggerating (Mt 4:9; Lk 4:6): the logic that governs the idolatrous kingdom has nothing to do with God.

To take, to ascend, to command; to grasp, to appear, to subjugate: these are the worst ways of dealing with others, who seem to be there only for utility, and to be stools, or to annoy us.

The lust for power is so irrepressible, so capable of seduction, that it seems to be a specific attribute of the divine condition: to be on high.

Although he could get ahead, Jesus did not want to confuse us by leading, but by shortening the distance.

In history, unfortunately, several churchmen have been unclear. They have willingly exchanged the apron of service and the towel of our feet for the torn chair and a coveted office.

Puppet idols not to be worshipped.

The final temptation - the culmination of the Temple's 'guarantee of protection' - seems like the others a trivial piece of advice in our favour. Even for 'success' in our relationship with God - after that with things and people.

But what is at stake here is full Trust in the Father's Action. He imparts life, ceaselessly strengthening and expanding our being.

Even in the opportunities that seem less appealing, the Creator ceaselessly generates opportunities for more genuine wholeness and fulfilment, which, reworked without hysteria, accentuate the wave of life.

He increasingly presses for the canons to be crossed. And the creaturely being transpires. Therein lurks a secret, a Mystery, a destination.

His is a thrust far from being planted on the spectacle-miracle, or on sacred assurance [which then shies away from unwelcome insights and risky risks].

A curious fact emerges in the Holy Scriptures: spiritually sluggish people are never tempted! And the reverse is also true.

It is the way of living and internalising the lightning or the time of Temptation that distinguishes Faith from the banality of any devotion.

Spiritual journey: why?

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

This is the First Sunday of Lent, the liturgical Season of 40 days which constitutes a spiritual journey in the Church of preparation for Easter. Essentially it is a matter of following Jesus who is walking with determination towards the Cross, the culmination of his mission of salvation. If we ask ourselves: “Why Lent? Why the Cross?”, the answer in radical terms is this: because evil exists, indeed sin, which according to the Scriptures is the profound cause of all evil. However this affirmation is far from being taken for granted and the very word “sin” is not accepted by many because it implies a religious vision of the world and of the human being.

In fact it is true: if God is eliminated from the world’s horizon, one cannot speak of sin. As when the sun is hidden, shadows disappear. Shadows only appear if the sun is out; hence the eclipse of God necessarily entails the eclipse of sin. Therefore the sense of sin — which is something different from the “sense of guilt” as psychology understands it — is acquired by rediscovering the sense of God. This is expressed by the Miserere Psalm, attributed to King David on the occasion of his double sin of adultery and homicide: “Against you”, David says, addressing God, “against you only have I sinned” (Ps 51(50):6).

In the face of moral evil God’s attitude is to oppose sin and to save the sinner. God does not tolerate evil because he is Love, Justice and Fidelity; and for this very reason he does not desire the death of the sinner but wants the sinner to convert and to live. To save humanity God intervenes: we see him throughout the history of the Jewish people, beginning with the liberation from Egypt. God is determined to deliver his children from slavery in order to lead them to freedom. And the most serious and profound slavery is precisely that of sin.

For this reason God sent his Son into the world: to set men and women free from the domination of Satan, “the origin and cause of every sin”. God sent him in our mortal flesh so that he might become a victim of expiation, dying for us on the Cross. The Devil opposed this definitive and universal plan of salvation with all his might, as is shown in particular in the Gospel of the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness which is proclaimed every year on the First Sunday of Lent. In fact, entering this liturgical season means continuously taking Christ’s side against sin, facing — both as individuals and as Church — the spiritual fight against the spirit of evil each time (Ash Wednesday, Opening Prayer).

Let us therefore invoke the maternal help of Mary Most Holy for the Lenten journey that has just begun, so that it may be rich in fruits of conversion.

[Pope Benedict, Angelus, 13 March 2011]

Doing a good deed almost instinctively gives rise to the desire to be esteemed and admired for the good action, in other words to gain a reward. And on the one hand this closes us in on ourselves and on the other, it brings us out of ourselves because we live oriented to what others think of us or admire in us (Pope Benedict)

Quando si compie qualcosa di buono, quasi istintivamente nasce il desiderio di essere stimati e ammirati per la buona azione, di avere cioè una soddisfazione. E questo, da una parte rinchiude in se stessi, dall’altra porta fuori da se stessi, perché si vive proiettati verso quello che gli altri pensano di noi e ammirano in noi (Papa Benedetto)

Since God has first loved us (cf. 1 Jn 4:10), love is now no longer a mere “command”; it is the response to the gift of love with which God draws near to us [Pope Benedict]

Siccome Dio ci ha amati per primo (cfr 1 Gv 4, 10), l'amore adesso non è più solo un « comandamento », ma è la risposta al dono dell'amore, col quale Dio ci viene incontro [Papa Benedetto]

Another aspect of Lenten spirituality is what we could describe as "combative" […] where the "weapons" of penance and the "battle" against evil are mentioned. Every day, but particularly in Lent, Christians must face a struggle […] (Pope Benedict)

Un altro aspetto della spiritualità quaresimale è quello che potremmo definire "agonistico" […] là dove si parla di "armi" della penitenza e di "combattimento" contro lo spirito del male. Ogni giorno, ma particolarmente in Quaresima, il cristiano deve affrontare una lotta […] (Papa Benedetto)

Jesus wants to help his listeners take the right approach to the prescriptions of the Commandments given to Moses, urging them to be open to God who teaches us true freedom and responsibility through the Law. It is a matter of living it as an instrument of freedom (Pope Francis)

Gesù vuole aiutare i suoi ascoltatori ad avere un approccio giusto alle prescrizioni dei Comandamenti dati a Mosè, esortando ad essere disponibili a Dio che ci educa alla vera libertà e responsabilità mediante la Legge. Si tratta di viverla come uno strumento di libertà (Papa Francesco)

In the divine attitude justice is pervaded with mercy, whereas the human attitude is limited to justice. Jesus exhorts us to open ourselves with courage to the strength of forgiveness, because in life not everything can be resolved with justice. We know this (Pope Francis)

Nell’atteggiamento divino la giustizia è pervasa dalla misericordia, mentre l’atteggiamento umano si limita alla giustizia. Gesù ci esorta ad aprirci con coraggio alla forza del perdono, perché nella vita non tutto si risolve con la giustizia; lo sappiamo (Papa Francesco)

The true prophet does not obey others as he does God, and puts himself at the service of the truth, ready to pay in person. It is true that Jesus was a prophet of love, but love has a truth of its own. Indeed, love and truth are two names of the same reality, two names of God (Pope Benedict)

Il vero profeta non obbedisce ad altri che a Dio e si mette al servizio della verità, pronto a pagare di persona. E’ vero che Gesù è il profeta dell’amore, ma l’amore ha la sua verità. Anzi, amore e verità sono due nomi della stessa realtà, due nomi di Dio (Papa Benedetto)

“Give me a drink” (v. 7). Breaking every barrier, he begins a dialogue in which he reveals to the woman the mystery of living water, that is, of the Holy Spirit, God’s gift [Pope Francis]

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.