Argentino Quintavalle

Argentino Quintavalle è studioso biblico ed esperto in Protestantesimo e Giudaismo. Autore del libro “Apocalisse - commento esegetico” (disponibile su Amazon) e specializzato in catechesi per protestanti che desiderano tornare nella Chiesa Cattolica.

33rd Sunday in O.T. (year C)

(2 Thessalonians 3:7-12)

2 Thessalonians 3:7 For you know how you ought to imitate us, because we did not live idly among you,

2 Thessalonians 3:8 nor did we eat anyone's bread without paying for it, but we worked hard night and day, labouring and toiling so that we would not be a burden to any of you.

2 Thessalonians 3:9 Not that we had no right to this, but to give you an example to imitate.

Paul says: remember our behaviour, that during our work among you, instead of shirking our duty to earn a living, we took on hard work so as not to be supported by the community. Paul, even before being a teacher, practises what he preaches. Every preacher must be able to combine theory and practice.

Conscience is educated not only through teaching, but above all through life, through example. Others must not only hear what is good and true, but they must also see what is good and true, because faith is either visible or it is not faith. Paul is not only a teacher who preaches, admonishes and teaches the faith, he is first and foremost someone who shows all these things and shows them through his life. He is both a teacher of life and a teacher of words. The two must always go together. It would be a serious spiritual loss if the two were to be separated.

Here, therefore, it is not a question of remembering a teaching, but of the duty to imitate the preachers of the gospel, who were not idlers. In other words, the preachers of the gospel did not take advantage of the hospitality of some Christians. Let us be clear, Paul is not saying that he never ate for free in other people's homes, but that he never demanded his sustenance.

Paul subjected himself to the harsh law of work for the sake of the gospel; he did not want to be mistaken for one of those itinerant preachers who moved from place to place selling theories, often only illusions, in exchange for sustenance. By supporting himself with his own hands, the apostle freed his message from any suspicion, and to do so he had renounced his right to be supported. This is the fairness of the apostle.

But there is also another reason why Paul worked: 'so as not to be a burden to any of you', a reason of charity. He did not want to cause difficulties for anyone, even if that anyone would have gladly done so.

Three principles are at stake here: the principle of justice, that of charity and that of evangelisation. The principle of justice says that every worker is entitled to his wages. Paul offers them the life of the soul; the Thessalonians offer him what he needs for the life of his body. This is justice: one thing for one thing, a gift for a gift, a service for a service.

But Paul does not want his relationship with the Thessalonians to be based on justice. For reasons of the gospel, he wants it to be based on charity instead. Charity is a one-way gift. Paul wants to give and that's it. He has decided to make his life a service of love. By proclaiming the gospel and living it in its deepest essence, he leaves the Thessalonians with the true model of how to live the gospel, how to proclaim it and how to put it into practice.

Now, if they want, they know what the Gospel is, they know it because they have seen it in Paul. Having seen it, they too can proclaim it and put it into practice. Paul decides to preach the Gospel freely because the Gospel is the free gift of God's love in Christ through the work of the Holy Spirit.

In the painful decline of the Church today, there are those who hope for a rebirth from below. But the Church was born from the proclamation of the apostles. It is up to those in charge to shed light, bring clarity, and point out the paths to follow in accordance with the Gospel of Christ... but those in charge must also be supported and encouraged.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse - Exegetical Commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

Dedication of the Lateran Basilica

(1 Cor 3:9c-11, 16-17)

1 Corinthians 3:9c You are God's building.

1 Corinthians 3:10 According to the grace of God given to me, like a skilled master builder I laid a foundation, and someone else is building upon it. But let each one take care how he builds upon it.

1 Corinthians 3:11 For no one can lay any foundation other than the one already laid, which is Jesus Christ.

1 Corinthians 3:16 Do you not know that you are God's temple and that God's Spirit dwells in you?

1 Corinthians 3:17 If anyone destroys God's temple, God will destroy him. For God's temple is holy, and you are that temple.

Evangelising means laying the foundation, that is, Jesus Christ, the Saviour and Redeemer, the Messiah of God for the salvation of all who believe. But the foundation is not enough. Paul says that he worked like a skilled architect. He acknowledges that he always acted with wisdom, but he also acknowledges that he only laid the foundation of faith in Corinth. It is then up to those who come after him to build on that foundation.

There are those who lay the foundation and those who build on it; there are those who dig deep and those who raise the building up to the sky. Without this communion of work, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to work in the Lord's vineyard. However, Paul does not stop at enunciating the principles of communion, but warns: let everyone be careful how they build!

Anyone who should or would want to build God's building without the foundation that is Jesus Christ would work in vain, waste their time unnecessarily, and there would be no salvation. Christ is the cornerstone of God's house. Our faith confesses that He alone is the Redeemer of humanity, the Messiah of God, the Saviour of mankind. Our faith confesses that Jesus is the way to access God and for God to dwell and live in our hearts.

Placing Jesus Christ as the foundation of God's building has only one meaning: placing his cross as the only way of salvation and redemption. And just as there is one foundation, so too must there be one building, one community of believers in Christ. When we forget our calling, which is to attain perfect conformity to Christ and his cross, each of us may be tempted to make ourselves the foundation, the cornerstone. When this happens, it is the destruction of the one building. Small huts arise where each person becomes lord and god over his brothers and sisters. The community of believers itself dies, lacking the principle of unity, and in this way everyone goes their own way and follows winding paths that do not lead to salvation.

For this reason, Paul warns everyone to be careful how they build upon it. But also to be careful to build only on this one foundation, which is Jesus Christ.

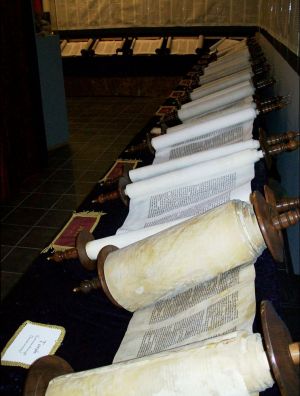

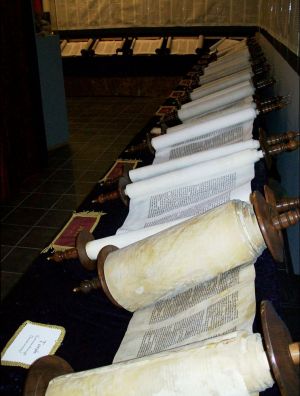

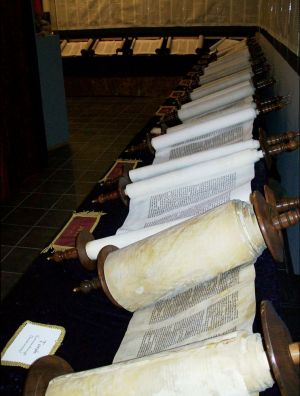

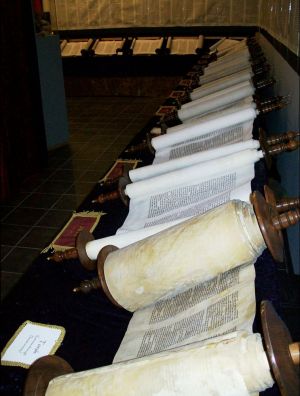

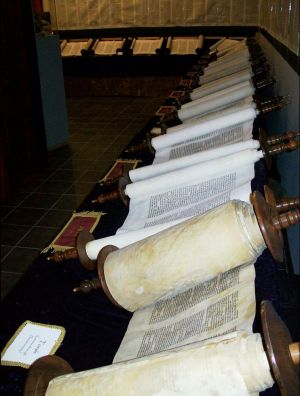

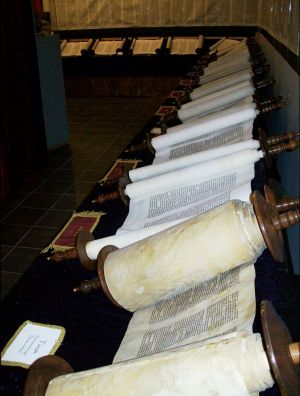

Being God's temple means that God dwells in us. The temple is God's dwelling place on earth. Before, the temple was made of stone, a house in the middle of the city of men. In Israel, there was only one temple, only one house of God, just as there was only one people of the Lord. One God, one people, one temple, one presence of God among the people.

"If anyone destroys God's temple, God will destroy him; for God's temple is holy, and you are that temple," says Paul. The Christian, therefore, must be the one who brings the living presence of God into the world. Those who see the Christian must feel that God dwells in him. But all this cannot happen unless the Christian is transformed into holiness, truth and charity.

How is the temple of God destroyed? There are several ways to destroy it. Here are a few.

The first way is to live a life that is different from that of Christ, when the body of Christ is made a body of sin and evil. Consider that Jesus Christ, in obedience to God, allowed himself to be nailed to the cross, exposing his body, the true temple of God, to every kind of suffering and deprivation. How can such a holy body be transformed by Christians into a body of sin, vice, and every other kind of evil? Either we believe that with Christ we are one body and that there can be no difference in holiness with Him, and then we truly change our way of life, or else the body of Christ, the temple of God, will be ruined. Sin destroys holiness in us, and by destroying it in us, it also diminishes it in the body of Christ, which then becomes ineffective in its witness and gift of salvation in the world.

The second way is to create an infinity of bodies of Christ, of temples in which we would like the Lord to live. This happens when each person does not build his faith on Christ, but pursues his own thoughts. That is, if you destroy brotherhood, you destroy fatherhood, you destroy yourself as a son: it is perdition. So it is not that I can say: I try to be good, but I am not interested in the community and others. No, because without others you destroy yourself, because you do not realise your true dimension, which is to be a child, that is, a brother. Whenever the body of Christ is damaged, the one who damages it is also damaged. It is only in the body of Christ that we have salvation. Those who place themselves outside the body of Christ also place themselves outside salvation.

So many who say (Luther docet) God yes and the Church no, it is serious! It is true destruction theorised as good.

These images of the building and the temple express what the Church is, which is the way in which it expresses our life as children, that is, brotherhood, and where each person expresses it in full freedom and responsibility for the gift they have received. The Church is a differentiated organism. What is the difference? It is something very important that must be mutually accepted, but with responsibility it must be put at the service of union and not division. Otherwise, I destroy myself.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse - exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All Generations Will Call Me Blessed

Catholics and Protestants Compared – In Defence of the Faith

The Church and Israel According to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed

(Rom 5:5-11)

Romans 5:5 And hope does not disappoint, because the love of God has been poured out into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.

Romans 5:6 For while we were still sinners, Christ died for the ungodly at the appointed time.

Romans 5:7 Now, it is rare to find anyone willing to die for a righteous person; perhaps there may be someone who has the courage to die for a good person.

Romans 5:8 But God proves his love for us in that, while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.

Romans 5:9 Much more then, having now been justified by his blood, we shall be saved from the wrath of God through him.

Romans 5:10 For if, when we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of his Son, much more, having been reconciled, we shall be saved by his life.

Romans 5:11 Not only that, but we also boast in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have now received reconciliation.

Romans 5:5 And hope does not disappoint us, because God's love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.

Hope does not disappoint, says St Paul. We know nothing about our tomorrow. Our relationship of grace with God does not take us out of life's problems, but far from being discouraged, if we go deeper we will realise that, within the struggles of life, what matters is our relationship with God. If I have a relationship based on hope, even if I experience daily struggles, suffering, and illness, I realise that despite everything, the weight of life is bearable; I have the capacity to endure. Thus, hope placed in God—a theological virtue—does not disappoint, because it has its roots in God's love, and God will never disappoint those who place their hope in Him.

What is disappointment? It is expecting something and then not receiving it. It is being convinced that there will be a better tomorrow, when in reality nothing comes but misery and pain. Disappointment is hope that is not fulfilled. It is hope that does not keep its promise. None of this happens in the hope placed in God through Jesus Christ. Why? "Because God's love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us." God has poured all His love into us. We may ask ourselves whether the genitive "love of God" is objective or subjective, that is, whether God is the object of man's love or whether God is the subject who loves. In other words, is the hope that does not disappoint because we love God, or because God loves us? It is more likely that it is God's love for us that makes our hope firm. As a pledge and seal of this love, God has given us his Holy Spirit.

However, the hope placed in God will always clash with a future that cannot be seen with the eyes of the flesh, because it is only visible with the eyes of faith. It should be noted that in this passage there is no explicit reference to faith, but faith is always to be assumed, since hope can only be established on the foundation of faith, and without faith there can be no Christian hope.

This must be said to avoid misunderstandings that often creep into the minds of many who would like a hope that does not disappoint but without possessing a firm faith in Christ. It is impossible to desire the fruits of faith without faith. Christians must grow in their understanding of the link between faith and hope, because too often they feel disappointed by God, when in truth it is Christians who have disappointed God because they have ceased to have faith in Him; or their faith is not true and therefore, in reality, theirs is non-faith.

"For while we were still sinners, Christ died for the ungodly at the appointed time" (v. 6). Literally, St Paul says that we were "asthenōn", without strength, in a state of spiritual infirmity. We were far from God, slaves to evil, and God offered us the death of His only Son for our redemption. Christ's death was not spent by the Father on good people, but on the "wicked," a term that expresses man's opposition to God. So the Father sacrifices his Son on behalf of people who are hostile to him. There is no greater demonstration of love than that given to us by God, and there never will be. This is why our hope in God can never disappoint us, since God did this while we were sinners, enemies, far away. So let us stop being afraid of God; let us stop being focused on ourselves and our miseries. Let us open ourselves to his love and live our lives with confidence and hope.

It is interesting that Paul uses the present tense, 'God demonstrates his love' (v. 8), even though the cross is in the past. The fact is that Christ's death is an ever-present proof of God's love; the historical event of the cross continues to be a present reality for the redemption of sinners and their reconciliation with God. Even though Christ died two thousand years ago, this fact continues to be the greatest manifestation of God's love for mankind.

We might also ask ourselves why it is the demonstration of God's love (v. 8) and not the demonstration of Christ's love, since it is Christ who died for us. The answer is that the Father and Christ are one, so that what Christ does can be credited to the Father, and vice versa. Thus, the pain and suffering that Christ endured in his atoning death were also the pain and suffering of the Father, and in Christ's death, the love of the Father is demonstrated as well as that of the Son.

Paul wants believers in Christ to be sure, certain. These verses of his become a hymn to hope and joy: if even now, while we are still fragile and sinful, we have overcome the fear of God, how much more should we be confident and joyful to meet him at the end of our lives.

Those who look at the cross must be filled with certainty, and this certainty is the love of God that triumphs over human sin. Once we live as reconciled people, reconciliation bears the fruit of salvation. All those who have lived as reconciled people will be saved. Salvation comes from living as truly reconciled people, living as true children of God.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All Generations Will Call Me Blessed

Catholics and Protestants Compared – In Defence of the Faith

The Church and Israel According to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

30th Sunday in Ordinary Time (year C)

(Lk 18:9-14)

Luke 18:9 He also told this parable to some who were confident of their own righteousness and despised others:

Luke 18:10 "Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector.

Luke 18:11 The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, 'God, I thank thee, that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this publican.

Luke 18:12 I fast twice a week; I give tithes of all that I get.

Luke 18:13 But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even lift up his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast, saying, 'God, be merciful to me, a sinner.

Luke 18:14 I tell you, this man went down to his house justified, rather than the other; for everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but he who humbles himself will be exalted.

This parable is a catechesis on prayer, which must be humbly trusting, entrusting oneself to the Father. Two men are presented who go up to Jerusalem to pray and are immediately described as diametrically opposed: a Pharisee and a tax collector. Two paradigmatic figures, whose contrast is immediately highlighted: the darkness of the Pharisee's light and the light of the tax collector's darkness. Two figures placed there to challenge the conscience of those who are going up to Jerusalem with Jesus. Ultimately, we are faced with a judgement of condemnation on those who rely on themselves and of reward on those who, instead, rely on God.

Verse 9 provides the key to understanding the parable. Although we are faced with an evaluation of the behaviour of some towards others, this has to do with prayer, which, it should not be forgotten, is a relationship with God, in which one's relationship with others weighs heavily. This is a short story that strikes at an inner attitude that creates discrimination, rejection and closure towards others and is such as to make one's relationship with God himself precarious. It is no coincidence, in fact, that the parable, which began by highlighting one's relationships with others, ends by highlighting one's relationship with God and such as to involve one's own justification (v. 14).

The Pharisee is an emblematic figure, whom Paul masterfully describes in Romans 2:1: 'You are therefore inexcusable, whoever you are, O man who judges'. This judgement stems from a conviction of legal holiness. However, this legal holiness is not reflected in their daily lives. In short, they are a class of right-thinking people who like to present themselves as scrupulous observers of the Law, but whose way of life contradicts this.

Alongside this figure, an icon of ritual purity and legal holiness, is the despised tax collector, who in the Gospels is often associated with sinners or prostitutes, characters who were socially and religiously ghettoised and considered already destined for eternal damnation. People, therefore, to be avoided so as not to become contaminated and ritually impure. Furthermore, approaching them or lingering with them certainly damaged the dignity of this class of religious people. The comparison in the parable is jarring, but it serves to make the final judgement (v. 14) more disruptive, thus highlighting God's way of thinking, which often contrasts with that of men. The social figure of the tax collector, precisely because of his work as a tax collector on behalf of the Roman oppressor, was considered, from a religious point of view, to be in a constant state of ritual impurity, as he was in constant contact with the pagan world. He was socially unpopular and hated because he was part of the oppressive system of the invader and often added his own interests to the taxes. To all intents and purposes, he was considered a public sinner.

Verses 11-12 are dedicated to the Pharisee, who, in his relationship with God, displays all his arrogance, which contrasts sharply with the behaviour of the tax collector. The Pharisee stands before God 'standing upright'. Although this was the way the pious Jew prayed, the verb statheìs says much more than simply standing before God. He places himself in a sort of defiant attitude before God, almost provocatively urging him to find some shadow in him, the perfect observer of the Law. And here he displays all his skill in legal observance, which is flawless, but which reveals all his insolent arrogance towards God, placing himself, in fact, on a par with him. And to make it stand out even more, he invokes not only the general sinfulness of men, placing himself above humanity ("I am not like other men"), but also the loser and despised publican, present there with him, whom he feels he far surpasses. The Pharisee's entire prayer unfolds within a tense confrontation with others, defined as thieves, unjust, adulterers, and his scrupulous observance of the Law, which goes far beyond what it required in terms of fasting, which was only expected once a year on the Day of Atonement. At the centre of his prayer and his relationship with God is not God, but only his ego, which here imposes itself before God to the detriment of others.

In contrast to such pride, we have the figure of the tax collector, diametrically opposed to that of the Pharisee. The Pharisee's 'standing' is contrasted with the tax collector's 'standing at a distance', which indicates not only the distance between him and the Pharisee, but also that between him and God. He is and feels himself to be a sinner. All he can offer God is his fragility, which does not even allow him to raise his eyes to Him, so great is his awareness of his nothingness. Instead, he entrusts himself to divine mercy, without expecting anything, because he is aware of his sin. But his going up to the Temple, his entering it, associates him in some way with the figure of the Prodigal Son, who returned to his Father's house, who does not even listen to the words of his lost and found son, but welcomes him with an embrace, which is a promise of eternal life.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, true God and true Man in the mystery of the Trinity

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

29th Sunday in O.T. (year C)

(Ex 17:8-13)

Exodus 17:8 Then Amalek came to fight against Israel at Rephidim.

Exodus 17:9 Moses said to Joshua, 'Choose some men for us and go out to fight against Amalek. Tomorrow I will stand on top of the hill with the staff of God in my hand.

Exodus 17:10 Joshua did as Moses commanded him and fought against Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill.

Exodus 17:11 When Moses held up his hands, Israel prevailed, but when he let them down, Amalek prevailed.

Exodus 17:12 And Moses' hands grew weary, so they took a stone and put it under him, and he sat on it, and Aaron and Hur supported his hands, one on one side and one on the other. So his hands remained steady until the sun went down.

Exodus 17:13 Joshua defeated Amalek and his people and put them to the sword.

This story follows the murmuring of the people of Israel in the desert because of the lack of water. What were the consequences of giving in to temptation? The liberation of the forces of evil represented by Amalek. There is a struggle and an effort to remain in the faith given by the Lord, and there is the war that is waged by Satan when he sees that our faith in God is wavering. Amalek, king of a people who lived on the edge of the desert, south of the land of Canaan, who comes to fight against Israel at Rephidim, represents all this.

The battle against the enemy is not fought by all men, but only by those who are chosen/elected by Joshua (a figure of Jesus) and place themselves under his command. It is a war that involves leaving ("go out to battle") daily life, abandoning all occupations, for total commitment. One does not fight against the evil one alone, but together with the whole Church, under the guidance of the one appointed by the Lord, under the protection of the 'staff of God' that gives victory: a staff that in the story is placed in Moses' hand.

Previously, Moses had to strike the rock with his staff to bring forth water; now he must do the same with his God and Lord: Moses must strike God with his staff so that God may bring forth victory for the Israelites. The rock was struck twice, and water flowed out of it in abundance. In order to be victorious over Amalek, God must be touched until complete victory is achieved. When the staff does not touch God, the victory belongs to Amalek. When the staff touches God, the victory belongs to Joshua and the Israelites. A momentary victory is of no use to Israel. What is needed is a definitive victory, the withdrawal of Amalek and peace in Israel.

'Joshua did as Moses commanded him and fought against Amalek, while Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill' (v. 10). Joshua does as Moses commands him. He chooses his best troops and goes to fight against Amalek. Moses does not climb to the top of the hill alone. He takes Aaron and Hur with him. They do not go against the enemy, but draw close to God. Only closeness to the Lord is a guarantee of victory, but one must climb the mountain to touch the sky and reach Him.

What happens on the mountain is an image of what happens on the battlefield. When Moses raises his hands and touches God, victory is Israel's. When Moses lowers his hands and lets them fall, Amalek prevails and wins. When God is not touched, grace does not flow, victory does not come. When God is touched, grace and victory come.

But man tires of keeping his arms raised to touch the Lord. However, if the Lord is not touched, the battle will always turn towards evil for us, no longer towards good. This is where intelligence comes to man's aid. Aaron and Hur find a way to prevent Moses from tiring. Satan is not defeated by our strength, but by the incessant prayer that the servant of God raises to heaven. A prayer that stops halfway is worthless and ineffective: it must be an unceasing commitment and a continuous fullness.

Since Moses grows tired of keeping his arms raised towards Heaven, Aaron and Hur take a stone, place it under him, and he sits down. The two of them, one on one side and the other on the other, support his hands. In this way, Moses' hands remain raised until sunset. Here we see that intelligence and wisdom are put at the service of a greater good. Moses contributes the spiritual part, Aaron and Hur the material part. The material and spiritual parts must always become one.

Human hands cannot remain raised towards God continuously: we do not have the strength. We need support for our weariness, enabling us to remain present in the struggle even when we are at rest. All this is given to us by Christ, the rock of salvation.As long as the battle lasts, that is, until the end of this existence, we must not abandon a spirit of continuous prayer. It is a guarantee of certain victory against the enemy. The Lord fights for us, gives us strength and courage to resist the evil one, and ensures that we are not overwhelmed by the weariness of a struggle that seems to have no end.

'Joshua defeated Amalek and his people, putting them to the sword' (v. 13). Supported by the strength of God, invoked without interruption by Moses, and sustained by Aaron and Hur, Joshua defeated Amalek and his people, putting them to the sword. Victory is achieved. However, it is the fruit of a threefold communion: Moses, Aaron and Hur, Joshua. Moses touches God. Aaron and Hur help him materially, physically. Joshua achieves victory by fighting, risking his own life. This is true communion: God and man working together. Thus our enemies are put to flight. The evil one and his children are forced to desist from their evil intent.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

28th Sunday in O.T. (year C)

(Lk 17:11-19)

Luke 17:11 On his way to Jerusalem, Jesus passed through Samaria and Galilee.

Luke 17:12 As he entered a village, ten lepers came to meet him. They stood at a distance

Luke 17:13 and raised their voices, saying, 'Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!

Luke 17:14 When Jesus saw them, he said, "Go and show yourselves to the priests." And as they went, they were cleansed.

Luke 17:15 One of them, when he saw that he was healed, came back, praising God in a loud voice.

Luke 17:16 and he threw himself at Jesus' feet to thank him. He was a Samaritan.

Luke 17:17 But Jesus asked, "Were not all ten cleansed? Where are the other nine?

Luke 17:18 Was no one found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?" And he said to him,

Luke 17:19 'Get up and go; your faith has saved you.

The coming of Jesus, his life, his preaching, his movement among men have as their primary and sole purpose their salvation, which is accomplished in Jerusalem, where he is going.

The scene described in this passage involves a group of people afflicted with leprosy. Whether this is leprosy as we understand it today, as an infection caused by Hansen's bacillus, we cannot know. The term that recurs in the biblical texts is sāra'at, which the LXX translates as 'leprosy'. Both terms are very imprecise generics used to indicate spots and rough patches that could appear on the skin, but also on clothing and even on the walls of houses. The Law required that the diagnosis be made by a priest.

Once the priest declared the person undergoing his assessment to be unclean, the afflicted man had to live outside the city or village and live in segregation or together with other unfortunate people, crying out to everyone that he was unclean in order to prevent others from approaching him. But the cry of "unclean" is here replaced by a cry for help: "Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!"This substitution recorded by Luke should not be overlooked, as it is an indication of how the new faith based on Jesus has in fact replaced the very prescriptions of the Mosaic Law, which allowed the afflicted man only a cry that revealed his state of condemnation and gave him no escape. It is as if to say that the Law condemns, but Jesus saves.

What appears here is a group of ten lepers. The number ten symbolises totality, fullness, completeness, and represents the Jewish world as a whole, evaluated in its relationship with Jesus. They are lepers who invoke the name of Jesus, they go to meet him, but they remain distant from him, they are still bound to the Mosaic Law, believing that true salvation can only be obtained through it. In fact, in going to the priests, that is, in continuing to submit to the Mosaic Law, the ten are not truly healed, but only purified. There was no contact with Jesus, there were no words of healing from Jesus, but only a command to continue under the Mosaic Law, which can guarantee purification but does not produce true salvation. Jesus, moreover, does not disown the Mosaic Law, but he does not attribute to it an intrinsic saving power, which only he can give. A Law, therefore, that saves only halfway, that is, it is capable of showing man the right way; of showing what is good and what is evil, but the true capacity for salvation, which transcends human capabilities, depends solely on faith in Jesus, on opening oneself existentially to him, welcoming him into one's life. And this is what the Samaritan will do.

The passage highlights a fundamental distinction between healing and salvation: the former concerns only the physical aspect, but says nothing more; while the latter gives new meaning to healing, it becomes a sign of inner regeneration. Healing only tells what the healed person can see, but for him it does not become a sign, it is only a stroke of luck for having found a cheap healer. Therefore, the healed person is only healed, but not saved. But this is not what happens to the Samaritan, who, returning on his steps, recognises in his healing the work of God's power, manifested in Jesus. For this reason, he is not only healed, but also saved (v. 19).

Significant for understanding the dynamics of salvation are verses 15-16, divided into three parts: a) the awareness on the part of the healed man: 'seeing that he was healed'. The verb here is in the theological or divine passive ("iathē" = he was healed), which in the language of the Gospels refers to God as the agent of healing. The healed man, therefore, recognises that what has happened to him is not the work of a simple healer, but the work of God himself. b) His praising God aloud, giving public testimony to what has happened to him. c) This praise is preceded and accompanied by two actions that reveal what has happened to this man: "he turned back" and "fell at Jesus' feet to thank him" (v. 16). That "turning back" describes the very act of conversion and rapprochement with Jesus. This man, like the others, stopped far from Jesus and, together with the others, had left him to submit to Mosaic ritualism. But the reading of faith that he developed about his healing ("since he was healed") prompts him to return to himself and retrace his steps: from Judaism to Christianity. A return that ends with him prostrating himself before Jesus, thanking him for the salvation he had given him.

Verse 16 ends with a polemical note, contrasting the pagan world with the Jewish world: "He was a Samaritan," considered by the Jews to be a heretic, a traitor to the faith of the Fathers and equated with the pagans. This polemic continues in verses 17-18, which aim to highlight the figure of the Samaritan, deliberately placed in a harsh and victorious confrontation with Judaism, and which sound like a condemnation of Judaism itself.

Verse 19 provides the key to understanding the healing, which for this Samaritan is transformed into true salvation, the nature of which is signified entirely in that "arise" (Anastàs), a technical term that in the language of the early church alluded to the resurrection of Jesus. The healing of this Samaritan, therefore, is in some way equated with the resurrection of Jesus and is linked to it - and flows from it into him. This healing, therefore, takes on the characteristics of a true regeneration to new life, which makes the Samaritan a new creature in Christ, while his physical healing becomes a sign of it. And what produces this salvation is the faith of this Samaritan: "your faith has saved you". Jesus is the source of salvation for all, but his salvation works effectively only in faith, that is, in those who open themselves existentially to him, recognising their need for healing ("have mercy on us") and seeing in Jesus their guide and their sure foundation ("Jesus, master").

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Apocalypse – exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers – Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ, True God and True Man in the Trinitarian Mystery

The Prophetic Discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants in comparison – In defence of the faith

The Church and Israel according to St Paul – Romans 9-11

(Available on Amazon)

3rd Sunday in Lent (C) - (1Cor 10,1-6.10-12)

(1Cor 10,1-6.10-12)

3rd Sunday in Lent (year C)

1Corinthians 10:1 For I do not want you to be ignorant, O brethren, that our fathers were all under the cloud, all crossed the sea,

1Corinthians 10:2 all were baptized in relation to Moses in the cloud and in the sea,

Paul, in this passage, refers us to the history of the past, to the lesson of history. He reminds us of the deeper meaning of history, which is the history of salvation. It is said that history is a teacher of life, but the pupils learn nothing. Paul instead says that from the history of Israel one must learn. The history of Israel is not just any history, but it is a way in which divine revelation was historically manifested. Revelation, in fact, was not manifested through the explanation of concepts, but through certain historical facts that are then also read and interpreted. The history of Israel is an exemplary history, so it is right and proper, if one wants to understand Jesus Christ, to see all the sacred history that prepares him. Among other things, this also accustoms us to reading our own little personal history, which is also salvation history because the Lord walks with us.

"For I do not want you to be ignorant": The Corinthians were supposed to know the facts narrated here, but the apostle wants them to know the typological significance that these facts have, and which is not to be ignored. Jesus Christ is the end result of a long journey, and we must know the journey that preceded it. Paul is very respectful of Israel's history and feels he must tell it. He refers us to these examples from the past that are extraordinary events, but they are also events of sin, and yet always instructive because they show what God's way is.

"Our fathers". Christians can consider the ancient Israelites as their fathers, because the Church succeeded the synagogue, and they are the true heirs and children of Abraham.

"They were all": Three times Paul repeats this expression. As if to say that salvation had been given to all. For all were led by the cloud, that is, by the presence of God, and all crossed the sea. All gained freedom from slavery and all were guided by God on the way to the promised land. Hence, on God's part, no exclusion, no preference towards some at the expense of others. He brought all his people out of Egypt, for all he parted the sea, for all he willed the cloud. All were in the condition of grace and truth that would enable them to conquer the promised land and possess it forever.

This universality of grace and truth for Paul is akin to a baptism. There is an immersion also of the children of Israel, even though their baptism is merely a figure of that instituted by Jesus Christ. However, there is a true immersion of the Israelites in the sea and in the 'cloud' and this immersion for them is true salvation, true deliverance.

Israel lived under the cloud, that mysterious cloud that guided the Israelites through the desert and sheltered them from the sun: signifying the presence of God, the Shekinah. To be under the cloud is to be under God's protection. They crossed the sea and were baptised: the passage from the land of slavery, which is Egypt, to the promised land, takes place through the crossing of the Red Sea, and this is a baptism because it signifies the detachment from the slavery of Egypt, liberation and purification, and the journey to the promised land.

"To be of Moses". Moses, the mediator of the old covenant, was a figure of Jesus Christ, and the Israelites led by him to the promised land were a figure of the Christians led by Jesus Christ to heaven. Now, just as Christians through baptism are incorporated into Jesus Christ and made subject to him as their Lord, whose laws they are bound to observe, so for the Israelites the mysterious cloud and the crossing of the Red Sea were a kind of baptism, whereby they remained subject to Moses and obliged to observe his laws. From that moment on, the people were separated from Egypt forever and belonged to the God who liberated them and to the prophet-mediator whom God gave them as their leader.

The mysterious cloud, a perceptible sign of God's presence, and of the favour He bestowed on His people, was a figure of the Holy Spirit, who is given in the baptism of Jesus Christ, and similarly the dry-foot passage through the Red Sea and the consequent deliverance from the bondage of Pharaoh, were figures of our deliverance from the bondage of sin through the waters of baptism.

Having stated this truth, Paul reminds us that it is not enough to come out of Egypt to have the promised land. The going out is one thing, the conquest and possession of the land is another. Between going out and conquering the land, there is a whole desert to cross. For the Israelites, the desert lasted for forty years; for Christians it lasts their whole life.

With baptism we come out of the slavery of sin, with a life of perseverance striving to conquer the kingdom of heaven we walk towards the glorious resurrection that will take place on the last day.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Revelation - exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants compared - In defence of the faith

(Buyable on Amazon)

31st Sunday in Ordinary Time (B)

Ps 17 (18)

This monumental ode, which the title attributes to David, is a Te Deum of the king of Israel, it is his hymn of thanksgiving to God because he has been delivered from all his enemies and from the hand of Saul. David acknowledges that God alone was his Deliverer, his Saviour.

David begins with a profession of love (v. 2). He shouts to the world his love for the Lord. The word he uses is 'rāḥam', meaning to love very tenderly, as in the case of a mother's love. The Lord is his strength. David is weak as a man. With God, who is his strength, he is strong. It is God's strength that makes him strong. This truth applies to every man. Every man is weak, and remains so unless God becomes his strength.

God for David is everything (v.3). The Lord for David is rock, fortress. He is his Deliverer. He is the rock in which he takes refuge. He is the shield that defends him from the enemy. The Lord is his mighty salvation and his bulwark. The Lord is simply his life, his protection, his defence. It is a true declaration of love and truth.

David's salvation is from the Lord (v. 4). It is not from his worthiness. The Lord is worthy of praise. God cannot but be praised. He does everything well. It is enough for David to call upon the Lord and he will be saved from his enemies. Always the Lord answers when David calls upon him. David's salvation is from his prayer, from his invocation.

Then David describes from what dangers the Lord delivered him. He was surrounded by billows of death, like a drowning man swept away by waves. He was overwhelmed by raging torrents. From these things no one can free himself. From these things only the Lord delivers and saves.

David's winning weapon is faith that is transformed into heartfelt prayer to be raised to the Lord, because only the Lord could help him, and it is to Him that David cries out in his distress. This is what David does: in his distress, he does not lose himself, he does not lose his faith, he remains whole. He turns his faith into prayer. He invokes the Lord. He cries out to Him. He asks Him for help and succour. God hears David's voice, hears it from his temple. His cry reaches him.

God becomes angry because He sees His elect in danger. The Lord's anger produces an upheaval of the whole earth. The earth trembles and shakes. The foundations of the mountains shake. It is as if a mighty earthquake turned the globe upside down. The spiritual fact is translated into such a profound upheaval of nature that one has the impression that creation itself is about to cease to exist. In this catastrophe that strikes terror, the righteous is rescued.

The Lord frees David because he loves him. Here is the secret of the answer to the prayer: the Lord loves David (v. 20). The Lord loves David because David loves the Lord. Prayer is a relationship of love between man and God. David invokes God's love. God's love responds and draws him to safety.

"Wholesome have I been with him, and I have guarded myself from guilt" (v. 24). David's conscience testifies for him. David prayed with an upright conscience, with a pure heart. This he says not only to God, but to every man. Everyone must know that the righteous is truly righteous. The world must know the integrity of God's children. We have a duty to confess it. It is on integrity that truly human relationships can be built. Without integrity, every relationship is tightened on falsehood and lies.

"The way of God is straight, the word of the Lord is tried by fire" (v. 31). What is the secret because God is with David? It is David's abiding in the Word of God. David has a certainty: the way indicated by the Word of God is straight. One only has to follow it. This certainty is lacking in the hearts of many today. Many do not believe in the purity of God's Word. Many think that it is now outdated. Modernity cannot stand under the Word of God.

"For who is God, if not the Lord? Or who is rock, if not our God?" Now David professes his faith in the Lord for all to know. Is there any other God but the Lord? God alone is the Lord. God alone is the rock of salvation. To seek another God is idolatry. This profession of faith must always be made aloud (remember the 'Creed'). Convinced people are needed. A faith hidden in the heart is dead. A seed placed in the ground springs up and reveals the nature of the tree. Faith that is in the heart must sprout up and reveal its nature of truth, holiness, righteousness, love and hope. A faith that does not reveal its nature is dead. It is a useless faith.

"He grants his king great victories; he shows himself faithful to his anointed, to David and his seed for ever" (v. 51). In this Psalm, David sees himself as the work of God's hands. That is why he blesses him, praises him, magnifies him. God's faithfulness and great favours for David do not end with David. God's faithfulness is for all his descendants. We know that David's descendants are Jesus Christ. With Jesus God is faithful for ever. With the other descendants, God will be faithful if they are faithful to Jesus Christ.

Here, then, the figure of David disappears to make way for that of the perfect king in whom the saving action that God offers the world is concentrated. In the light of this reinterpretation, the ode entered the Christian liturgy as a victory song of Christ, the 'son of David', over the forces of evil and as a hymn of the salvation he offered.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Revelation - exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?

Jesus Christ true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants compared - In defence of the faith

(Buyable on Amazon)

An ancient hermit says: “The Beatitudes are gifts of God and we must say a great ‘thank you’ to him for them and for the rewards that derive from them, namely the Kingdom of God in the century to come and consolation here; the fullness of every good and mercy on God’s part … once we have become images of Christ on earth” (Peter of Damascus) [Pope Benedict]

Afferma un antico eremita: «Le Beatitudini sono doni di Dio, e dobbiamo rendergli grandi grazie per esse e per le ricompense che ne derivano, cioè il Regno dei Cieli nel secolo futuro, la consolazione qui, la pienezza di ogni bene e misericordia da parte di Dio … una volta che si sia divenuti immagine del Cristo sulla terra» (Pietro di Damasco) [Papa Benedetto]

And quite often we too, beaten by the trials of life, have cried out to the Lord: “Why do you remain silent and do nothing for me?”. Especially when it seems we are sinking, because love or the project in which we had laid great hopes disappears (Pope Francis)

E tante volte anche noi, assaliti dalle prove della vita, abbiamo gridato al Signore: “Perché resti in silenzio e non fai nulla per me?”. Soprattutto quando ci sembra di affondare, perché l’amore o il progetto nel quale avevamo riposto grandi speranze svanisce (Papa Francesco)

The Kingdom of God grows here on earth, in the history of humanity, by virtue of an initial sowing, that is, of a foundation, which comes from God, and of a mysterious work of God himself, which continues to cultivate the Church down the centuries. The scythe of sacrifice is also present in God's action with regard to the Kingdom: the development of the Kingdom cannot be achieved without suffering (John Paul II)

Il Regno di Dio cresce qui sulla terra, nella storia dell’umanità, in virtù di una semina iniziale, cioè di una fondazione, che viene da Dio, e di un misterioso operare di Dio stesso, che continua a coltivare la Chiesa lungo i secoli. Nell’azione di Dio in ordine al Regno è presente anche la falce del sacrificio: lo sviluppo del Regno non si realizza senza sofferenza (Giovanni Paolo II)

For those who first heard Jesus, as for us, the symbol of light evokes the desire for truth and the thirst for the fullness of knowledge which are imprinted deep within every human being. When the light fades or vanishes altogether, we no longer see things as they really are. In the heart of the night we can feel frightened and insecure, and we impatiently await the coming of the light of dawn. Dear young people, it is up to you to be the watchmen of the morning (cf. Is 21:11-12) who announce the coming of the sun who is the Risen Christ! (John Paul II)

Per quanti da principio ascoltarono Gesù, come anche per noi, il simbolo della luce evoca il desiderio di verità e la sete di giungere alla pienezza della conoscenza, impressi nell'intimo di ogni essere umano. Quando la luce va scemando o scompare del tutto, non si riesce più a distinguere la realtà circostante (Giovanni Paolo II)

The ability to be amazed at things around us promotes religious experience and makes the encounter with the Lord more fruitful. On the contrary, the inability to marvel makes us indifferent and widens the gap between the journey of faith and daily life (Pope Francis)

La capacità di stupirsi delle cose che ci circondano favorisce l’esperienza religiosa e rende fecondo l’incontro con il Signore. Al contrario, l’incapacità di stupirci rende indifferenti e allarga le distanze tra il cammino di fede e la vita di ogni giorno (Papa Francesco)

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.