XVI Sunday in Ordinary Time (B) [21 July 2024]

1. Jesus Christ, breaking down the wall of separation that divided us, has made us one. This is the good news we find in the second reading of this Sixteenth Sunday of Ordinary Time taken from St Paul's Letter to the Ephesians. The Apostle is in Rome under house arrest in a rented house and one of his first thoughts during his imprisonment is to write to his dear brothers in faith, Ephesians, Colossians, Philippians and to Philemon, presenting himself not as a prisoner of Caesar, but as a prisoner of Christ. He focuses the Letter to the Ephesians on the Church, a universal body composed of all those who are saved through faith in Christ Jesus. A new unity has been created by God through the reconciling work of the Cross (2:16) and thus Jews and Gentiles have become part of God's family, in which all racial, cultural and social barriers are broken down. There is only one Church of which Christ is the Head, and there are three images Paul uses to describe its nature: the Church is an edifice founded on the apostles and prophets of which the cornerstone is Christ; it is one body and one spirit; it is the Bride of Christ and a model of fellowship in every relationship, primarily in the family between husband, wife and children. Knowing well the situation of those communities, which he himself founded and which are still marked by discord and contrasts, St Paul hopes that his chains will help to encourage and support believers who suffer for the preservation of the faith. The difficulty of living together among both Jewish and pagan converts is the experience he had already had in the first communities he founded and which continued to be fuelled by misunderstandings and even violent clashes. It was in Antioch of Pisidia that he understood the realisation of the first great turning point in the history of revelation when, encountering the violent opposition of the Jews, he declared that after their refusal to convert to Christ, he would direct his preaching to the Gentiles (Acts 13:46). In the letter to the Ephesians he develops the theme of reconciliation between Christians of Jewish origin and those of pagan origin who have become brothers and therefore all with the same possibility of access, in one Spirit, to the one heavenly Father. He writes in this regard that of Israel and the pagans, Christ made one people "breaking down the wall of separation". Such a union seemed unattainable to many, and the Apostle's concern continued to the end to safeguard the unity that he unfortunately saw in serious danger. It was not a matter of operational choices, but the heart of the problem touched the very content of the Christian faith. For Paul the only thing that matters is that Jews and Gentiles through baptism are equally immersed in the new life of the Risen Christ and therefore every barrier that separates them must be broken down. And speaking of barriers he had in mind something that everyone knew well: the barrier that on the Temple esplanade in Jerusalem separated the space reserved for members of the people of Israel (men, women, priests), from the rest of the square where everyone could pass, Jews and non-Jews, circumcised and uncircumcised, members or not of the chosen people, people educated to the Mosaic Law and people who were not. A signpost formally forbade non-Jews to enter on pain of death, and St Paul had experienced the risk of being killed, as we read in the Acts of the Apostles because they thought he had brought in a certain Trophimus from Ephesus (Acts 21:27-31). That barrier is for St Paul an icon of the "wall of enmity", so marked between Jews and pagans because the Jews, circumcised out of loyalty to the Mosaic law, despised and called the pagans "the uncircumcised". In the Letter to the Ephesians, he then insists on God's new plan for the baptised people, a plan of love and reconciliation that concerns the whole of every community, the peoples of the whole world and even the whole of creation.

2. The theme of communion, unity and forgiveness returns frequently in the Gospels and New Testament writings. It also constitutes a prevailing aspiration in the preaching of the Church Fathers showing us the face of the Churches of that time already dotted with examples of goodness but threatened by the virus of division and religious contrasts that sometimes intertwined with civil strife. This indicates that the difficulty in achieving the communion desired by Christ is a constant challenge to the faith of every baptised person. Despite goodwill and efforts, we experience, in the world and in the Church, how difficult it is to get along. Unity and communion remain an aspiration that clashes with the fragility of life, and this has been the case, as history clearly shows, since the origin of humanity, ever since man was created to be in friendship with God and chose his autonomy, which soon proved to be a harbinger of misunderstandings and divisions, clashes and violence where the strongest think they can win by prevailing in so many ways over the weakest, the different, the enemy. Yet these words of the Apostle Paul continue to resonate in the consciousness of humanity: 'Jesus came to proclaim peace to you who were far away and peace to those who were near'. How then can we internalise this proclamation of salvation when we hear simmering enmity and division between believers? There is talk of peace and unity, but the scandal of division persists, creating walls to bar life to different peoples, gates to well protect the spaces reserved for one's own group and one's own convictions, while in the general climate, beyond the declarations of understanding and peace, there is a growing dislike of the other that leads to gestures of rejection, often identifying him as an adversary and as an 'enemy'. Despite the scandal of disunity, however, there is no shortage of examples and gestures of courage, forgiveness, and reconciliation that show how much stronger than hatred is love, beyond appearances, and we believe that the last word will always be Love's capable of healing conflicts and divisions. This invincible hope sustains us and gives us strength.

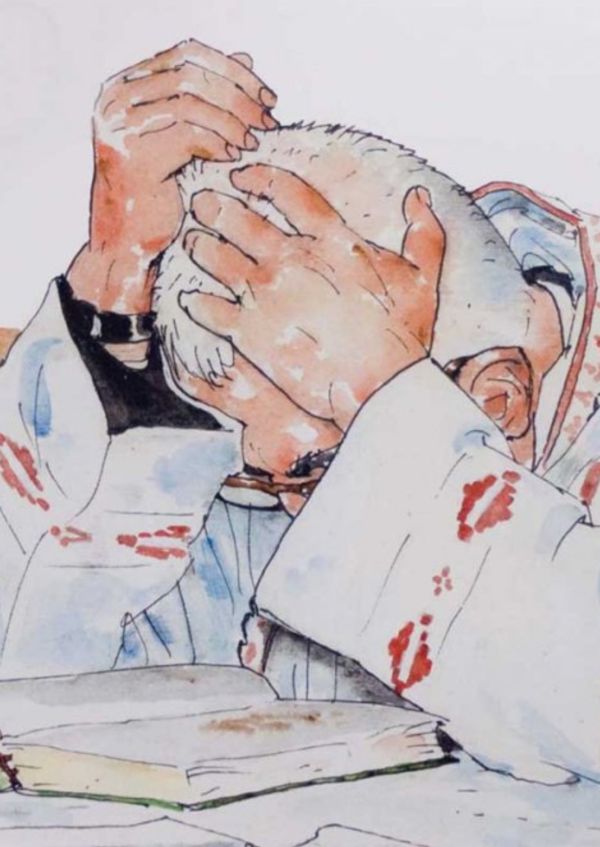

3. "Come away, you alone, into a deserted place, and rest a while". The Gospel page offers us a space of quiet to understand how not to give in to life's anxieties, divisions and conflicts that destroy peace in hearts. For the first time, St Mark calls these disciples "apostles", and this indicates that Jesus is now calling them to share his own mission, which includes, alongside immersion in pastoral action, the need for adequate spaces of silence and solitude. To the Twelve who enthusiastically return from the first apostolic expedition and would like to immediately recount how it went, Jesus says first of all: Rest! Silence and prayer are needed for every apostle so that he does not forget that he is not the saviour of the world: we are only fragile instruments in the hands of God, and to the extent that we do not separate ourselves from him, we can become agents of his peacemaking. A holy priest, an apostle of charity, Don Oreste Benzi loved to repeat: 'To stand before the world, one must remain on one's knees before God'. If Jesus shares with the disciples his anguish at seeing the "great crowd" of whom he has compassion because they seem like sheep without a shepherd, he first of all asks his own to spend some time alone with him. The crowd that presses, notes the evangelist Mark, can wait even if they come from Galilee and from all parts of Judea, Idumea, Transjordan, the region of Tyre and Sidon, and there are also the religious authorities who make war on him and sow hatred to the point of crucifying him. To go into action, the Lord is in no hurry: he wants each apostle to understand and marry with his life his own passion for souls with the inevitable difficulties and opposition that it entails. He does not ask the apostle for a strong social commitment, but communicates to him his divine compassion expressed by the evangelist with the Greek term "SPLANGKNA", which defines the movement of interiority, that is, the depth of being, and in Hebrew "RAHAMIN", translated as mercy. God's name is Mercy, love that leads to Christ's sacrifice to break down and destroy every wall of division, diversity and hatred. Unlike the evangelist John, St Mark does not develop the theme of the good shepherd, but presents it in filigree in these very words: Jesus "saw a great crowd, had compassion on them because they were like sheep that have no shepherd". Only Christ can give us the gift of his compassion so that we are not seized by the prophet Jeremiah's rebuke, which is very clear in the first reading: 'woe to the shepherds who cause my pasture to perish and scatter'.

+Giovanni D'Ercole. Happy Sunday

P.S. I attach a reflection on the Temple, taken from a lecture by Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi. "The world is like the eye: the sea is the white, the earth is the iris, Jerusalem is the pupil and the image reflected in it is the temple". This ancient rabbinic aphorism sharply and symbolically illustrates the function in the temple according to an intuition that is both primordial and universal. Two ideas underlie the image. The first is that of the cosmic 'centre' that the sacred place must represent... the outer horizon, with its fragmentation and its tensions, converges and subsides in an area that by its purity must embody the meaning, the heart, the order of the whole being. In the temple, therefore, the multiplicity of the real is "con-centred", finding in it peace and harmony... From the temple, then, a breath of life, of sanctity, of illumination is "de-centred", transfiguring the everyday and the ordinary texture of space. And it is at this point that the second theme underlying the Jewish saying evoked above enters the scene. The temple is the image that the pupil reflects and reveals. It is, therefore, a sign of light and beauty. Put another way, we could say that sacred space is an epiphany of cosmic harmony and a theophany of divine splendour... It is curious that symbolically, the three monotheistic religions anchor themselves in Jerusalem around three sacred stones, the Western Wall (popularly known as the 'Wailing Wall'), a sign of the Solomonic temple for the Jews, the rock of Muhammad's ascension to heaven in the mosque of Omar for Islam, and, indeed, the upturned stone of the Holy Sepulchre for Christianity. On the last page of the New Testament, when John the Seer looks out over the plan of the new Jerusalem of perfection and fullness, he is confronted with a fact that is disconcerting at first sight: "I saw no temple in it, for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are its temple" (Revelation, 21, 22). Between God and man there is no longer any need for spatial mediation; the encounter is now between persons, the divine life intersects with human life in a direct way...God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship him in spirit and in truth" (John 4: 21-24). There will be a further turning point that will settle the divine presence in the very 'flesh' of humanity through the person of Christ, as the famous prologue of John's Gospel declares: 'The Word became flesh and pitched his tent among us' (1:14), ... Paul will go further and, writing to the Christians of Corinth, will affirm: 'Do you not know that your body is the temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you... Glorify therefore God in your body!" (i, 6, 19-20). "A temple of living stones", therefore, as St Peter will write, "employed for the construction of a spiritual building" (i, 2, 5) a sanctuary not extrinsic, material and spatial, but existential, a temple in time. The architectural temple will, therefore, always be necessary, but it must have in itself a symbolic function: it will no longer be an intangible and magical sacred element, but only the necessary sign of a divine presence in history and in the life of humanity. The temple, therefore, does not exclude or exorcise the square of civil life, but fertilises, transfigures and purifies its existence, giving it a further and transcendent meaning. We end our reflection with three testimonies. The first is a medieval Hebrew cabbalistic chant that recalls the various steps to find the place where one truly encounters God. The refrain in Hebrew...with a play on words and a dazzling insight says: 'He, God, is the Place of every place, / and yet this Place has no place'. The second testimony is linked to the figure of St Francis. A friar says to Francis: "We have no more money for the poor". Francis replies: "Strip the altar of the Virgin and sell its furnishings, if you cannot otherwise meet the needs of those in need". And immediately afterwards he adds: "Believe me, it will be dearer to the Virgin that the gospel of her Son be observed and her altar bare, than to see the altar adorned and the Son in the son of man despised". The third and final consideration is offered to us by Orthodox spirituality. A well-known twentieth-century Russian lay theologian who lived in Paris, Pavel Evdokimov, declared that between the square and the temple there should not be a barred door, but an open threshold so that the swirls of incense, the chants, the prayers of the faithful and the flickering of the lamps are also reflected in the square where laughter and tears, and even blasphemy and the cry of despair of the unhappy person resound. Indeed, the wind of God's Spirit must run between the sacred hall and the square where human activity takes place. In this way, one finds the authentic and profound soul of the Incarnation that weaves together space and infinity, history and eternity, the contingent and the absolute.