don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

Rhythm of Nature. The evolutionary factor

From below, not from a summit

(Mk 4: 26-34)

Here we are introduced to a different mentality, to a new Family, to another Kingdom, not very "elevated"; indeed, completely reversed. Different from that expected on a mighty mountain (Ez 17:22).

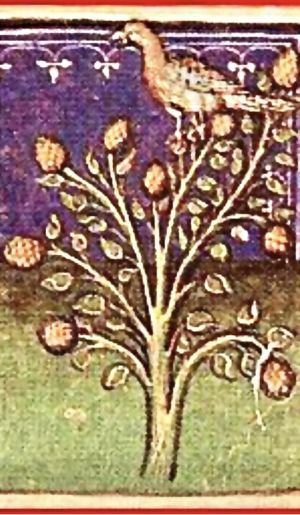

It will not be portrayed by the majesty of the cedar of Lebanon [which once covered the mountain slopes of the Near East] but by a simple shrub in the kitchen garden (Mk 4:32a).

And the very origins of this new reality will not come from the top of a lofty stem, but from a small seed, simply planted on the ground.

Little grain like the others. Nothing remarkable in itself. Which develops horizontally, rather (v.32b).

How much gas must be given to accelerate the spread of the Kingdom?

According to Jesus, we must wait for everyone to meet himself, without neuroses.

A proposal that knows no borders: it’s aimed at everyone. It is enough to let the grain do its normal things - thus integrating the energies; giving space, even giving way.

The Seed grows on its own, intertwined with the soil and climate, yet according to a deep individual character.

He escapes cerebral explanations: «How, it itself does not know» (v.27).

After sowing, the author of the gesture resumes normal life.

Letting it go, the little hidden grain walks its way, to the end.

This is the evolutionary factor.

No farmer tramples on his field, nor investigates what happens (bothering the seedlings): development, growth and maturation are in themselves guaranteed.

Anyone who wants to enter would disturb the sprouts.

Whoever dug to control the evolution of little bud that is intertwining its roots with the ground, would ruin everything.

Our sacred identity is inextricably linked to personal singularity: it entangles with an unrepeatable sensitivity and vicissitude.

It’s the darkness, the silence, the waiting, that make tender shoots sprout, in their uniqueness and authenticity.

They would only be harmed by the one who wanted to interfere, modifying, overlapping other patterns and trends - never conforming to the realities in spontaneous singular development.

Beware of the hastiness of those who immediately want a result other than to be ourselves in relation to the innate essence and personal mission, which emanate from the hidden Source.

Time of love is not immediate: it takes place along a path, whose periods cannot be marked by any hasty plan - only irritating - if not by the Spirit, so that we can manifest the intrinsic unprecedented.

No one can bother such exceptional wealth, which arises and develops «automatically» (v.28), so that we are enabled to give birth to the inner world, the quintessence, the Jesus who hatches in heart; not others.

«Laying hold of the scythe» (v.29) means that at this point the soul is awakened for the Kingdom, ready to ‘give life’ to itself and to brethren, overflowing its wholeness to others, even distant or wandering like birds (v.32).

Together, a Church that - without thinking too much about "how it should be" - convinces all those in need of shelter from the "heat".

And Seed can be transmitted anywhere by the same «volatiles» that settle there even just enough for each one to take flight again.

‘Parables of the kingdom’ in Mt 13 and here in Mk 4 do not narrate a solemn, epochal, majestic reality that stubborns and imposes itself.

Rather, the new kingdom will be comparable to a common shrub, which grows modestly - silent, in the home garden (v.32).

As if to say: we evolve into tiny signs - nothing extraordinary - but we are people, not facsimiles.

Thus we announce Paradise.

[Friday 3rd wk. in O.T. January 30, 2026]

Rhythm of Nature. The evolutionary factor

From below, not from a summit

(Mk 4: 26-34)

Here we are introduced to a different mentality, to a new Family, to another Kingdom, not very "elevated"; indeed, completely reversed. Different from that expected on a mighty mountain (Ez 17:22).

It will not be portrayed by the majesty of the cedar of Lebanon [which once covered the mountain slopes of the Near East] but by a simple shrub in the kitchen garden (Mk 4:32a).

And the very origins of this new reality will not come from the top of a lofty stem, but from a small seed, simply planted on the ground.

Little grain like the others. Nothing remarkable in itself. Which develops horizontally, rather (v.32b).

How much gas must be given to accelerate the spread of the Kingdom? According to Jesus, one must wait for each one to meet himself, without neurosis.

The Kingdom of God is the sphere in which He reigns: the alternative society that believers inaugurate here, not looking nose-up at the afterlife.

The new reality will transcend time, because it is characterised by love for all: it will transcend the chronicle and even history.

This is also why the Gospels do not borrow images mediated by a particular cult and the sacred.

To make it clear that the Churches are not even limited to the earthly spatial-temporal dimension, the Master pretends not to know that - even at a slow pace - after sowing, the farmer cleans the field, protects the scattered seed, irrigates.

It is not amnesia his, but a special emphasis on what counts and distinguishes the soul's affair, contended between religiosity and Faith.

The image is simple, paradoxically mediated by the culture of the fields - to explain the rhythm of life in the Spirit.

It will sprout from the soil, sprout and blossom on a foundation that is not shaky, a genuine foundation without vocational dissent, far from external prejudices - which we detest underneath.

Then, on the horizon of every stretch of the journey there is always a new plant, another genesis, a different flowering in the time of the seasons, a different effervescence to be introduced into the already capitalised arrangement.

In commentary on the Tao Tê Ching (ix), Master Wang Pi writes: "The four seasons succeed one another. When their work is done, they pass away'.

A proposal that knows no borders, it appeals to all. Just let the seed do its normal thing - thus integrating energies; giving space, and even yielding.

[This would ensure the continued attraction and maturation of people and communities].

It is not an esoteric ideal, measured on people set apart, exceptionally gifted, particular, and titled: it is for the "ordinary" man (v.26) - but not scatter-brained, and who at the moment when he has to activate himself casts aside, that is, destined for all mankind.

Then he waits, and it is here that he lays down voluntarism and opens the door to the dreaming side - no longer trying to correct spontaneous processes and set things right according to his head.

In fact, in vv. 26-29, the work of the farmer is reduced to: sowing the seed and putting his hand to the sickle [in the ancient world, not the time of verification and reckoning, but the turning point of the feast that made everyone feel fulfilled, and everyone rejoice].

The focus of life in the Spirit escapes the person's stubbornly active work.

The seed-Word-event is planted underground, stands in the dark, rots and takes root, without anyone being able to accelerate its development, or later pull up the shrub to make it stand out.

As the Tao (ix) says: 'He who fills up what he possesses, had better desist' - and even 'when the work is done, to withdraw is the Way of Heaven'.

Jesus does not say that God's Blessing can possibly be thrown into a narrow field, as a careful miser would do: the Message of Salvation must be radiated unsparingly.

His Word opens the brain and limits sectarian thoughts, inviting one to overlook any temptation to exclusivism and define boundaries. Why?

The Seed has a vitality of its own, which does not depend on the outside. An ivy climbs, an oak tree takes root; an undergrowth flower knows how to stay in the shade, a sunflower soars; so on.

The Grain is even capable of self-healing - thus leading to a process of more solid self-healing.

This Grain of the Word (in us: the personal Calling) possesses a silent power, a hidden, yet irresistible direction and strength - not dependent on emotional swings or advantageous situations.

Easily it can be trampled upon, but the vocation recoils.

The more you stifle it, the more it re-enters with renewed energy.

We cannot deny our inclination, except by strengthening it - or by creating and accentuating discomforts on an identity [not character] basis, i.e. not our own.

One Mission is not worth the other.

The Seed grows on its own, intertwined with the soil and the climate, yet according to deep individual character.

It defies cerebral explanation: 'How, he himself does not know' (v.27).

After the sowing season, it is useless - indeed, harmful - to attempt to drug the path of growth.

Nothing but a rhythm of spontaneous development can properly direct existence.

In fact, the doer resumes normal life.

Left to its own devices, the little hidden grain goes its own way, all the way down.

This is the evolutionary factor.

No farmer tramples on his field, nor does he investigate what is going on, importuning: development, growth and ripening are guaranteed for himself.

He who would enter would disturb the shoots.

Whoever would dig to check the grain that is intertwining its roots with the soil would ruin everything.Our sacred identity is inextricably bound up with personal singularity: it is entangled with an unrepeatable sensitivity and vicissitude.

Here, becoming One with the perennial Infant Christ, we recognise Him in us - and then we bear fruit.

It is the darkness, the silence, the waiting, that make the tender shoots sprout, in their uniqueness and authenticity.

It would only damage them if one wanted to interfere, modifying, superimposing patterns and trends... never conforming to realities in spontaneous singular development.

It is the classic forcing of those who must at all costs condition us, and impose beliefs that have nothing to do with it.

The result is an abortion, caused by external influence [indeed, of nosy 'guides'] that easily stunts development.

When we put prejudices and beliefs aside and let go of the instinct that sees the divine self, faithful in growth and surprises, we will be enchanted and amazed.

We will have confirmation of what we sensed: ours - so lived, intense, fragrant - is a profound and sensitive intelligence.

The assimilation of the Word of God and the call of the creaturely vocation intertwine in time.

Beware of the precipitation of those who immediately want a 'result' that is not to be ourselves in relation to the innate quintessence and personal mission, which emanate from the hidden Source.

[The anger that is sometimes triggered also brings authenticity out into the open. So that we manifest the kernel of unrepeatable inclination].

In short, the time of love is not immediate, it unfolds along a path, whose periods cannot be marked by hasty designs or spiritual guides, only irritating - if not by the 'Spirit'.

"Holy" because by its Action it cuts off the germs of death; it helps to distinguish what is life, and wants us to manifest the inherent unseen.

"Ruah haQodesh": the only trustworthy, inherent, caring Master, endowed with an unclouded mind. From the disruptive force - which throws all organised, 'safe' and too cerebral reality into the air; therefore close to death.

The dynamism may be very slow, but no one will stop it, despite the destruction it has suffered. It will pick up again after humiliations and holes in the water.

These are lacerating moments, but they are reinterpreted by the soul on the journey as precious indications: prohibitions of access and ways out, if not precise signals.

That is why - after transmitting the Message - no running: one must have respect for space and time for growth.

If the Word of God does not intertwine its vital course with the individual subject's life story, there is a risk of anaesthetising or alienating precisely the most motivated souls - albeit unskilled in terms of cunning; weak, sensitive.

It is then useless to defuse the symptoms of malaise when someone feels held hostage - a stranger to himself.

If we are forced to remove or hide our authentic emotions from the homologising opinions of the 'best', we will vainly resemble them - dispersing the richness of our Name.

If the expert, instead of helping to broaden the panorama, were to impose no change, the person who allows himself to be plagiarised would not rediscover his own simplicity.

And life (even that spent most nobly, in the gift of self) would sooner or later become a nightmare, constantly subject to manipulation, just around the corner.

Indeed, Jesus could not stand managers who pretended to intervene with their conformism and 'proper' lifestyles.

Enough, then, of "regents" who place under an asphyxiating cloak the path that is ours by nature.

There are times when the feverish and pressing work must go into the background, so that the masterpiece we are inside can grow on its own.

Thus the fruit will surprise and exceed normal or prescribed expectations.

If the beginning is small and hidden, the inner call will go in symbiosis with that of the Word.

In this way, even the call of events and the genius of the time will be well interpreted and assimilated, within the extraordinary nature of each.

Jesus seems to be against the work of directors who control the movement and behaviour [of all others - except their own].

They must only unfold the Message, not their own opinion; then keep silent and do not meddle in the affairs of others.

Only - try to foster the assimilation of the Word, and the multifaceted pursuit of one's outspoken character.

The natural path goes and evolves in symbiosis with a process of rooting God's Proclamation in us on our ledges.

No one can disturb this exceptional richness, which is born and develops 'automatically' (v.28 Greek text) so that we are enabled to give birth to the inner world, the essence, the Jesus that broods in our hearts; not others.

Incarnation: it only continues and enriches if we do not delegate the unparalleled freedom of movement.Unparalleled breath that acts as a catalyst for exceptional, unrepeatable, singularly individual though related potentialities; to full maturity.

Life always develops in such a way that it can be difficult for us to understand - but in the experience of fullness of being and inner attunement with oneself, there is not so much to understand as to experience.

The result will be an out-scaling that realises in the round, on every side the inclination of the person.

Like a gradual unfolding that then channels itself into a particular trajectory - now made astounding also in terms of relationships: already blissful; exuberant, luxuriant.

Personal and selfless.

"Laying hold of the sickle" (v.29) means that at this point the person of Faith is awakened for the Kingdom, ready to give life to himself and his brethren. Overflowing its experience of wholeness to others, even distant or wandering like birds (v.32).

Together, a Church that - without thinking too much about 'how it should be' - convinces all those in need of shelter from arsure.

An experience that will convince them, only if as sons and brothers we have listened to that need for listening and understanding - sometimes so unexpressed. Recharging passion, rekindling insight and life.

The Seed can be transmitted everywhere by the same "birds" (once only distant) that alight there, more or less enough for each one to take flight again and propose themselves to others - elsewhere - with interest.

The Kingdom of God is a living community, made up of believers who move and wait, transform and pull out of the field every varied, unconscious and dormant resource.

[The unexplored side - in fact - does not attract the attention of just any master. And the quality not designated from the outside is also likely to be overlooked, because it is not very magnificent (often not even explicit)].

"And he said: How shall we compare the Kingdom of God? Or in what parable shall we put it? Like a grain of mustard seed that when sown on the earth is smaller than all the seeds on earth" (Mk 4:30-31).

In short, the parables of the kingdom in Mt 13 and here in Mk 4 do not narrate a solemn, epochal, majestic, peremptory reality, which is self-evident and imposing.

Rather, the new kingdom will be likened to a common shrub, growing modestly - silently, in the kitchen garden (v.32) - among aubergines, lettuce, and cucumbers; daisies, weeds, and violets.

But for each one and without bounds.

To say: we each evolve into tiny signs - nothing extraordinary - but we are well-rounded persons, not puppets or facsimiles, nor merely extensions of the past.

We are not by character - we want to free ourselves from others' models - nor by prestige or unreachable (but trivial) excellence and showy grandiosity.

We remain nothing much, like the flowers of the undergrowth, or at most spinach; but we want to express ourselves without forcing.

We long to feel our vital energy circulating, leading out of the tedious, rambling herd.

After all, one can also love poorly - not something predictable, or someone who conditions and overpowers us.

Nightmares dissolve. This is how we proclaim Paradise.

To internalise and live the message:

What sense does the small hope of a few believers without a conspicuous, self-confident, doctrinal, and voluntarist heritage have for the social and cultural concert - today global -?

Rhythm Growth Contrast

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Today’s liturgy presents to us two short parables of Jesus: the parable of the seed that grows of its own accord and the parable of the mustard seed (cf. Mk 4:26-34). With images taken from the farming world the Lord presents the mystery of the Word and of the Kingdom of God, and points out the reasons for our hope and our dedication.

In the first parable the focus is on the dynamism of the sowing: the seed that was scattered on the land sprouts and grows by itself, whether the peasant is awake or asleep. The man sows with the trust that his work will not be fruitless. What supports the farmer in his daily efforts is specifically trust in the power of the seed and in the goodness of the soil. This parable recalls the mysteries of the creation and of redemption, of God’s fertile work in history. It is he who is the Lord of the Kingdom, man is his humble collaborator who contemplates and rejoices in the divine creative action and patiently awaits its fruits. The final harvest makes us think of God’s conclusive intervention at the end of time, when he will fully establish his Kingdom. The present is the time of sowing, and the growth of the seed is assured by the Lord. Every Christian therefore knows well that he must do all he can, but that the final result depends on God: this awareness sustains him in his daily efforts, especially in difficult situations. St Ignatius of Loyola wrote in this regard: “Act as though everything depended on you, but in the knowledge that really everything depends on God” (cf. Pedro de Ribadeneira, Vita di S. Ignazio di Loyola, Milan, 1998).

The second parable also uses the image of the seed. Here, however, it is a specific seed, the mustard seed, considered the smallest of all seeds. Yet even though it is so tiny, it is full of life; it breaks open to give life to a sprout that can break through the ground, coming out into the sunlight and growing until it becomes “the greatest of all shrubs” (Mk 4:32): the seed’s weakness is its strength, its breaking open is its power. Thus the Kingdom of God is like this: a humanly small reality, made up of those who are poor in heart, of those who do not rely on their own power but on that of the love of God, on those who are not important in the world’s eyes; and yet it is through them that Christ’s power bursts in and transforms what is seemingly insignificant.

The image of the seed is especially dear to Jesus, because it clearly expresses the mystery of the Kingdom of God. In today’s two parables it represents “growth” and “contrast”: the growth that occurs thanks to an innate dynamism within the seed itself and the contrast that exists between the minuscule size of the seed and the greatness of what it produces.

The message is clear: even though the Kingdom of God demands our collaboration, it is first and foremost a gift of the Lord, a grace that precedes man and his works. If our own small strength, apparently powerless in the face of the world’s problems, is inserted in that of God it fears no obstacles because the Lord’s victory is guaranteed. It is the miracle of the love of God who causes every seed of good that is scattered on the ground to germinate. And the experience of this miracle of love makes us optimists, in spite of the difficulty, suffering and evil that we encounter. The seed sprouts and grows because God’s love makes it grow. May the Virgin Mary, who, like “good soil”, accepted the seed of the divine Word, strengthen within us this faith and this hope.

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 17 June 2012]

Kingdom: Foundation that comes from God

1. As we said in the previous catechesis, it is not possible to understand the origin of the Church without taking into account all that Jesus preached and worked (cf. Acts 1:1). And it was precisely on this subject that he addressed his disciples and left us all a fundamental teaching in the parables about the Kingdom of God. Among these, of particular importance are those that enunciate and make us discover the character of historical and spiritual development that is proper to the Church according to the plan of its Founder himself.

2. Jesus says: "The Kingdom of God is like a man who sows a seed in the earth: sleep or wake, night or day, the seed germinates and grows; how, he himself does not know. For the earth produces spontaneously, first the stalk, then the ear, then the full grain in the ear. When the fruit is ready, immediately you put your hand to the sickle, because the harvest has come" (Mk 4:26-29). So the Kingdom of God grows here on earth, in human history, by virtue of an initial sowing, that is, of a foundation, which comes from God, and of a mysterious working of God himself, which continues to cultivate the Church down the centuries. In God's work for the Kingdom, the sickle of sacrifice is also present: the development of the Kingdom is not achieved without suffering. This is the meaning of the parable in Mark's Gospel.

3. We also find the same concept in other parables, especially those gathered in Matthew's text (Mt 13:3-50).

"The kingdom of heaven," we read in this Gospel, "can be compared to a mustard seed, which a man takes and sows in his field. It is the smallest of all seeds, but when it has grown, it is larger than all the other seeds and becomes a tree, so that the birds of heaven nestle among its branches" (Mt 13:31). This is the growth of the kingdom in the "extensive" sense.

Another parable, on the other hand, shows its growth in an "intensive" or qualitative sense, comparing it to the yeast, which a woman took and mixed with three measures of flour so that it all fermented" (Mt 13:32).

4. In the parable of the sower and the sowing, the growth of the Kingdom of God certainly appears as the fruit of the work of the sower, but it is in relation to the soil and the climatic conditions that the sowing produces harvest: "where the hundred, where the sixty, where the thirty" (Mt 13:8). The soil means the inner readiness of men. Therefore, according to Jesus, the growth of the Kingdom of God is also conditioned by man. Human free will is responsible for this growth. This is why Jesus recommends to all to pray: "Thy kingdom come" (cf. Mt 6:10; Lk 11:2): it is one of the first questions of the Pater noster.

5. One of the parables narrated by Jesus on the growth of the Kingdom of God on earth makes us discover very realistically the character of struggle that the kingdom entails, due to the presence and action of an "enemy", who "sows the weeds (or grass) in the midst of the wheat". Jesus says that when "the harvest flourished and bore fruit, behold, the weeds also appeared". The servants of the master of the field would like to pluck it, but the master does not allow them to do so, "lest . . . uproot the wheat also. Let the one and the other grow together until the harvest, and at the time of the harvest I will say to the reapers, 'Harvest the darnel first and bind it in bundles to burn it; but the wheat put it in my barn' (Mt 13:24-30). This parable explains the coexistence and often the intertwining of good and evil in the world, in our lives, in the very history of the Church. Jesus teaches us to see things with Christian realism and to treat every problem with clarity of principles, but also with prudence and patience. This presupposes a transcendent vision of history, in which we know that everything belongs to God and every final outcome is the work of his Providence. However, the final fate - with an eschatological dimension - of the good and the bad is not hidden: it is symbolised by the harvesting of the wheat in the storehouse and the burning of the tares.

6. The explanation of the parable about sowing is given by Jesus himself, at the disciples' request (cf. Mt 13:36-43). In his words emerges both the temporal and eschatological dimension of the Kingdom of God.

He says to his own: "To you has been confided the mystery of the Kingdom of God" (Mk 4:11). About this mystery he instructs them and, at the same time, by his word and his work he "prepares for them a kingdom, just as the Father (Son) has prepared it for him" (cf. Lk 22:29). This preparation is continued even after his resurrection: we read in the Acts of the Apostles that "he appeared to them for forty days and spoke to them of the Kingdom of God" (cf. Acts 1:3) until the day when "he was taken up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of God (Mk 16:19). These were the last instructions and dispositions to the Apostles on what they had to do after the Ascension and Pentecost to give a concrete start to the Kingdom of God in the origin of the Church.

7. The words addressed to Peter at Caesarea Philippi are also part of the preaching about the kingdom. In fact, he says to him: "To you I will give the keys of the kingdom of heaven" (Mt 16:19), immediately after having called him a stone, on which he will build his Church, which will be invincible against "the gates of hell" (cf. Mt 16:18). It is a promise expressed then with the verb in the future tense: "I will build", because the definitive foundation of the Kingdom of God in this world was yet to be accomplished through the sacrifice of the Cross and the victory of the Resurrection. After that, Peter, with the other Apostles, will have the living consciousness of their calling to "proclaim the wonderful works of him who called them out of darkness into his admirable light" (cf. 1 Pet 2:9). At the same time, all will also have an awareness of the truth that emerges from the parable of the sower, namely that "neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but God who makes it grow", as St Paul wrote (1 Cor 3:7).

8. The author of the Book of Revelation expresses this same kingdom consciousness when he relates the song addressed to the Lamb: "You were slain and redeemed for God with your blood men of every tribe and tongue and people and nation, and you made them for our God a kingdom of priests" (Rev 5:9-10). The Apostle Peter specifies that they were constituted as such "to offer sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ" (cf. 1 Pet 2:5). These are all expressions of the truths learnt from Jesus who, in the parables about the sower and the sowing of the seed, about the growth of the wheat and the weeds, about the mustard seed that is sown and then becomes a fairly large plant, spoke of a Kingdom of God that, under the action of the Spirit, grows in souls thanks to the life force resulting from his death and resurrection: a kingdom that grows until the time foreseen by God himself.

9. "Then shall be the end," announces St Paul, "when he (Christ) shall deliver up the kingdom to God the Father, having reduced all principality and power and might to nothing" (1 Cor 15:24). For when "all things have been subdued to him, he also, the Son, will be subdued to him who has subdued all things to him, that God may be all in all" (1 Cor 15:28).

In an admirable eschatological perspective of the Kingdom of God is inscribed the existence of the Church from the beginning to the end, and its history unfolds from the first to the last day.

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 25 September 1991]

Reasons for hope and commitment

Today’s Gospel is composed of two very brief parables: that of the seed that sprouts and grows on its own, and that of the mustard seed (cf. Mk 4:26-34). Through these images taken from the rural world, Jesus presents the efficacy of the Word of God and the requirements of his Kingdom, showing the reasons for our hope and our commitment in history.

In the first parable, attention is placed on the fact that the seed scattered on the ground (v. 26) takes root and develops on its own, regardless of whether the farmer sleeps or keeps watch. He is confident in the inner power of the seed itself and in the fertility of the soil. In the language of the Gospel, the seed is the symbol of the Word of God, whose fruitfulness is recalled in this parable. As the humble seed grows in the earth, so too does the Word by the power of God work in the hearts of those who listen to it. God has entrusted his Word to our earth, that is to each one of us with our concrete humanity. We can be confident because the Word of God is a creative word, destined to become the “full grain in the ear” (v. 28). This Word, if accepted, certainly bears fruit, for God Himself makes it sprout and grow in ways that we cannot always verify or understand. (cf. v. 27). All this tells us that it is always God, it is always God who makes his Kingdom grow. That is why we fervently pray “thy Kingdom come”. It is He who makes it grow. Man is his humble collaborator, who contemplates and rejoices in divine creative action and waits patiently for its fruits.

The Word of God makes things grow, it gives life. And here, I would like to remind you once again, of the importance of having the Gospel, the Bible, close at hand. A small Gospel in your purse, in your pocket and to nourish yourselves every day with this living Word of God. Read a passage from the Gospel every day, a passage from the Bible. Please don’t ever forget this. Because this is the power that makes the life of the Kingdom of God sprout within us.

The second parable uses the image of the mustard seed. Despite being the smallest of all the seeds, it is full of life and grows until it becomes “the greatest of all shrubs” (Mk 4:32). And thus is the Kingdom of God: a humanly small and seemingly irrelevant reality. To become a part of it, one must be poor of heart; not trusting in their own abilities, but in the power of the love of God; not acting to be important in the eyes of the world, but precious in the eyes of God, who prefers the simple and the humble. When we live like this, the strength of Christ bursts through us and transforms what is small and modest into a reality that leavens the entire mass of the world and of history.

An important lesson comes to us from these two parables: God’s Kingdom requires our cooperation, but it is above all the initiative and gift of the Lord. Our weak effort, seemingly small before the complexity of the problems of the world, when integrated with God’s effort, fears no difficulty. The victory of the Lord is certain: his love will make every seed of goodness present on the ground sprout and grow. This opens us up to trust and hope, despite the tragedies, the injustices, the sufferings that we encounter. The seed of goodness and peace sprouts and develops, because the merciful love of God makes it ripen.

May the Holy Virgin, who like “fertile ground” received the seed of the divine Word, sustain us in this hope which never disappoints.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 14 June 2015]

Lantern, Measure and prejudices

(Mk 4: 21-25)

Mk's is a narrative and popular catechesis, which reflects the problems of a very primitive community of Faith - compared to those of the other Gospels.

His way of expressing is correlative to these unsophisticated origins.

At the time, still in Rome there was a strong debate within the churches on essential issues.

Some believers clung to the mummified mentality of the mighty Messiah, who should have descended like a bolt of lightning and remained to himself.

A glorious King, comparable to the emperor, who ensured victories for his own. Solving every problem in a disruptive and immediate way.

Those who read the Scriptures with such criteria - or even as a scarcely popular text (v.22), to be interpreted in small doses, mysterious, cerebral, moralistic; typical - they made it difficult to internalize the meaning of the new Teaching. And to be well disposed in the real confrontation with the inevitable risks of the evangelical truth.

The Message of Christ, on the other hand, opens up to the uninterrupted apostolate; also troubled. And it must be proclaimed at the face of the world, otherwise the Spirit does not let loose within the disciple, nor does it work outside of him..

The Proclamation brings with it the awareness of having received much, and of having been introduced without conditions of perfection into the Secret of God; therefore, with the desire that everyone be part of it.

In Mc the language of the parables and of the images that the Lord uses to make his teaching explicit convey the sense of a non-esoteric or difficult to decipher reading of the things of the Kingdom of God - always lead back into the normal elements of life.

By transmitting Christ also in the new way that the Magisterium [practical and broad] is teaching us, we open up the secrets of the Father (v.22) - no longer tied to glosses, nor bound by fashions and reworked opinions on customs, or pious advice.

Of course, those who update and remain attentive, push forward.

No one will be surprised that the tacticians, the unwilling, or the nostalgic who linger and remain entrenched in their positions [ancient or latest] end up extinguishing their impact and gradually disappearing from the scene (vv.24-25).

The «lamp» that Comes and 'orients in the darkness of the evening' is only the Word of God, which is not to be smothered with customs or à la page ideas.

In the dark it must always be on, that is, it cannot remain closed in a book (v.21).

It is a ‘lantern that lights up’ only when it is combined with life - and with a non-triumphalist reading key, nor with a fixed circuit (v.21).

If not, it remains ambivalent (vv. 23-24). We must pay close attention to the codes with which we interpret Scripture, and our own impulses or prejudices.

Often entrenched [or spineless] ideas deflect the understanding of the meaning of events, the emotions they arouse, and the very Person of the Son of God.

Hers is an ‘outSize Light’ - which break in with the inevitable risk of the evangelical fragrance.

«Measure» that has no “limit”. Disproportion own, of the Announcement.

[Thursday 3rd wk. in O.T. January 29, 2026]

Lantern, Measure and Prejudice

The Risk of Truth

(Mk 4:21-25)

That of Mk is a narrative and popular catechesis, reflecting the problems of a very primitive community of Faith - compared to those of the other Gospels.

Its manner of expression is correlative to such unsophisticated (only practical and ordinary) origins.

Identifying Lao Tse's thought, Master Ho-shang Kung confesses: 'Since I do not see the form and appearance of the Way, I do not know by what name it is fitting to call it' (commentary on the Tao Tê Ching xxv,7-8).

At the time, there was still a strong debate within the churches in Rome on essential issues: Who is God and how to honour Him? What is the right relationship with Tradition? And between doctrine and life? How to realise oneself and love?

To be free ... must one give up everything, or change one's mind? How to face persecution? Is there room for Dreams? Who guides us? What to do with spontaneous nature? How to deal with institutions and the distant? And so on.

Some of the faithful remained attached to the mummified mentality of the mighty Messiah, who was supposed to descend like lightning and stay to himself.

A glorious king, comparable to the emperor, who would ensure victories for his people. He solved every problem in a disruptive and immediate way.

Those who read the Scriptures with such a criterion - or even as a scarcely popular text (v.22), to be interpreted in small doses, mysterious, cerebral, moralistic; typical - had difficulty internalising the sense of the new Teaching. And to be well prepared for the real confrontation with the inevitable risks of the gospel truth.

The Message of Christ, on the other hand, opens one up to an uninterrupted apostolate; even a troubled one. And it must be proclaimed in the face of the world, otherwise the Spirit will not be unleashed within the disciple, nor will it work outside him.

The proclamation brings with it an awareness of having received much, and of having been introduced unconditionally into the Secret of God; hence, with the desire for all to share in it.

In Mk, the language of the parables and images that the Lord uses to make his teaching explicit convey the sense of an interpretation that is neither esoteric nor difficult to decipher of the things of the Kingdom of God - always placed within the normal elements of life.

By transmitting Christ (also in the new way that the Magisterium is teaching us, practical and broad) we open up the secrets of the Father (v.22) - no longer bound by chicanery, or reworked opinions on customs, or pious advice.

Certainly, those who keep up to date and remain attentive, advance. No one will be surprised that the unwilling or nostalgic who linger and remain entrenched in their positions end up extinguishing their influence and gradually disappearing from the scene (vv.24-25).

The "lamp" that comes and directs in the darkness of the evening is only the Word of God, which is not to be suffocated with custom.

In the darkness it must always be lit, that is, it cannot remain closed in a book (v.21).

It is a lamp that only illuminates when it is united with life - and with a key that is neither triumphalist nor fixed (v.21).

Otherwise, it remains ambivalent (vv.23-24). We must be very careful about the codes with which we interpret Scripture, and our own impulses or prejudices.

Ingrained ideas often deflect our understanding of the meaning of events, the emotions they arouse, and the very Person of the Son of God.

Even today, some willing readers of the Bible remain hampered by hasty and one-sided ways of understanding, or cerebral thoughts, cultivated within clubs of supposedly chosen ones called apart.

Sometimes we remain conditioned by grand narratives (all in all conformist); by roundabout, disembodied, more or less sought-after options - even ecclesial ones. Some in the form of dynastic privileges and banal fanaticism, which threaten life in Christ with serious errors.

The Mystery of the Kingdom is not a monopoly that some narrow and demarcated caste can afford to jealously guard.

It is, on the contrary, like a Light that transcends any chosen language, overcoming hierontocracies, circles and oligarchies that would claim to hijack it - and with it hold the living Jesus hostage as well.

"Man is the being-limit that has no limit" (Fratelli Tutti n.150). Our burning desire, the founding Eros that impassions our soul, cannot be normalised, subjected to clichés.

In the itinerancy of the homo viator, the Word-Logos and the Word-event of the divine already in us becomes Clarity, the horizon of Life. It comes to illustrate, support and motivate every personalistic anthropology of the threshold and the beyond.

In short, the Principle that breaks through and calls is like an impulse beyond measure.

"And he said to them: Be careful what you listen to. By the measure with which you measure it will be measured to you, and it will be added to you. For whoever has will be given to him, and whoever does not have even what he has will be taken away from him" (vv.24-25).Disproportionality proper to the Gospel:

The Gospel cannot lose its fragrance, because the Friend penetrates our condition of finitude to make himself a virtue of ever new search.

Motive and Engine of Growth - with the inevitable risk of truth, which has no limit.

To internalise and live the message:

What is your unconditioned but luminous and growing form of active dedication?

Light or indistinct mist

In all churches, in cathedrals and religious houses, wherever the faithful gather to celebrate the Easter Vigil, that holiest of all nights begins with the lighting of the Paschal candle, whose light is then passed on to all who are present. One tiny flame spreads out to become many lights and fills the darkness of God’s house with its brightness. This wonderful liturgical rite, which we have imitated in our prayer vigil tonight, reveals to us in signs more eloquent than words the mystery of our Christian faith. He, Christ, who says of himself: “I am the light of the world” (Jn 8:12), causes our lives to shine brightly, so that what we have just heard in the Gospel comes true: “You are the light of the world” (Mt 5:14). It is not our human efforts or the technical progress of our era that brings light into this world. Again and again we experience how our striving to bring about a better and more just world hits against its limits. Innocent suffering and the ultimate fact of death awaiting every single person are an impenetrable darkness which may perhaps, through fresh experiences, be lit up for a moment, as if through a flash of lightning at night. In the end, though, a frightening darkness remains.

While all around us there may be darkness and gloom, yet we see a light: a small, tiny flame that is stronger than the seemingly powerful and invincible darkness. Christ, risen from the dead, shines in this world and he does so most brightly in those places where, in human terms, everything is sombre and hopeless. He has conquered death – he is alive – and faith in him, like a small light, cuts through all that is dark and threatening. To be sure, those who believe in Jesus do not lead lives of perpetual sunshine, as though they could be spared suffering and hardship, but there is always a bright glimmer there, lighting up the path that leads to fullness of life (cf. Jn 10:10). The eyes of those who believe in Christ see light even amid the darkest night and they already see the dawning of a new day.

Light does not remain alone. All around, other lights are flaring up. In their gleam, space acquires contours, so that we can find our bearings. We do not live alone in this world. And it is for the important things of life that we have to rely on other people. Particularly in our faith, then, we do not stand alone, we are links in the great chain of believers. Nobody can believe unless he is supported by the faith of others, and conversely, through my faith, I help to strengthen others in their faith. We help one another to set an example, we give others a share in what is ours: our thoughts, our deeds, our affections. And we help one another to find our bearings, to work out where we stand in society.

Dear friends, the Lord says: “I am the light of the world – you are the light of the world.” It is mysterious and wonderful that Jesus applies the same predicate to himself and to all of us together, namely “light”. If we believe that he is the Son of God, who healed the sick and raised the dead, who rose from the grave himself and is truly alive, then we can understand that he is the light, the source of all the lights of this world. On the other hand, we experience more and more the failure of our efforts and our personal shortcomings, despite our good intentions. In the final analysis, the world in which we live, in spite of its technical progress, does not seem to be getting any better. There is still war and terror, hunger and disease, bitter poverty and merciless oppression. And even those figures in our history who saw themselves as “bringers of light”, but without being fired by Christ, the one true light, did not manage to create an earthly paradise, but set up dictatorships and totalitarian systems, in which even the smallest spark of true humanity is choked.

At this point we cannot remain silent about the existence of evil. We see it in so many places in this world; but we also see it – and this scares us – in our own lives. Truly, within our hearts there is a tendency towards evil, there is selfishness, envy, aggression. Perhaps with a certain self-discipline all this can to some degree be controlled. But it becomes more difficult with faults that are somewhat hidden, that can engulf us like a thick fog, such as sloth, or laziness in willing and doing good. Again and again in history, keen observers have pointed out that damage to the Church comes not from her opponents, but from uncommitted Christians. “You are the light of the world”: only Christ can say: “I am the light of the world.” All of us can be light only if we stand within the “you” that, through the Lord, is forever becoming light. And just as the Lord warns us that salt can become tasteless, so too he weaves a gentle warning into his saying about light. Instead of placing the light on a lampstand, one can hide it under a bushel. Let us ask ourselves: how often do we hide God’s light through our sloth, through our stubbornness, so that it cannot shine out through us into the world?

Dear friends, Saint Paul in many of his letters does not shrink from calling his contemporaries, members of the local communities, “saints”. Here it becomes clear that every baptized person – even before he or she can accomplish good works – is sanctified by God. In baptism the Lord, as it were, sets our life alight with what the Catechism calls sanctifying grace. Those who watch over this light, who live by grace, are holy.

Dear friends, again and again the very notion of saints has been caricatured and distorted, as if to be holy meant to be remote from the world, naive and joyless. Often it is thought that a saint has to be someone with great ascetic and moral achievements, who might well be revered, but could never be imitated in our own lives. How false and discouraging this opinion is! There is no saint, apart from the Blessed Virgin Mary, who has not also known sin, who has never fallen. Dear friends, Christ is not so much interested in how often in our lives we stumble and fall, as in how often with his help we pick ourselves up again. He does not demand glittering achievements, but he wants his light to shine in you. He does not call you because you are good and perfect, but because he is good and he wants to make you his friends. Yes, you are the light of the world because Jesus is your light. You are Christians – not because you do special and extraordinary things, but because he, Christ, is your life, our life. You are holy, we are holy, if we allow his grace to work in us.

Dear friends, this evening as we gather in prayer around the one Lord, we sense the truth of Christ’s saying that the city built on a hilltop cannot remain hidden. This gathering shines in more ways than one – in the glow of innumerable lights, in the radiance of so many young people who believe in Christ. A candle can only give light if it lets itself be consumed by the flame. It would remain useless if its wax failed to nourish the fire. Allow Christ to burn in you, even at the cost of sacrifice and renunciation. Do not be afraid that you might lose something and, so to speak, emerge empty-handed at the end. Have the courage to apply your talents and gifts for God’s kingdom and to give yourselves – like candlewax – so that the Lord can light up the darkness through you. Dare to be glowing saints, in whose eyes and hearts the love of Christ beams and who thus bring light to the world. I am confident that you and many other young people here in Germany are lamps of hope that do not remain hidden. “You are the light of the world”. Where God is, there is a future! Amen.

[Pope Benedict, Vigil in Freiburg 24 September 2011]

Light

3. "You are the light of the world...". For those who first heard Jesus, as for us, the symbol of light evokes the desire for truth and the thirst for the fullness of knowledge which are imprinted deep within every human being.

When the light fades or vanishes altogether, we no longer see things as they really are. In the heart of the night we can feel frightened and insecure, and we impatiently await the coming of the light of dawn. Dear young people, it is up to you to be the watchmen of the morning (cf. Is 21:11-12) who announce the coming of the sun who is the Risen Christ!

The light which Jesus speaks of in the Gospel is the light of faith, God’s free gift, which enlightens the heart and clarifies the mind. "It is the God who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness’, who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God on the face of Christ" (2 Cor 4:6). That is why the words of Jesus explaining his identity and his mission are so important: "I am the light of the world; whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life" (Jn 8:12).

Our personal encounter with Christ bathes life in new light, sets us on the right path, and sends us out to be his witnesses. This new way of looking at the world and at people, which comes to us from him, leads us more deeply into the mystery of faith, which is not just a collection of theoretical assertions to be accepted and approved by the mind, but an experience to be had, a truth to be lived, the salt and light of all reality (cf. Veritatis Splendor, 88).

In this secularized age, when many of our contemporaries think and act as if God did not exist or are attracted to irrational forms of religion, it is you, dear young people, who must show that faith is a personal decision which involves your whole life. Let the Gospel be the measure and guide of life’s decisions and plans! Then you will be missionaries in all that you do and say, and wherever you work and live you will be signs of God’s love, credible witnesses to the loving presence of Jesus Christ. Never forget: "No one lights a lamp and then puts it under a bushel" (Mt 5:15)!

Just as salt gives flavour to food and light illumines the darkness, so too holiness gives full meaning to life and makes it reflect God’s glory. How many saints, especially young saints, can we count in the Church’s history! In their love for God their heroic virtues shone before the world, and so they became models of life which the Church has held up for imitation by all. Let us remember only a few of them: Agnes of Rome, Andrew of Phú Yên, Pedro Calungsod, Josephine Bakhita, Thérèse of Lisieux, Pier Giorgio Frassati, Marcel Callo, Francisco Castelló Aleu or again Kateri Tekakwitha, the young Iroquois called "the Lily of the Mohawks". Through the intercession of this great host of witnesses, may God make you too, dear young people, the saints of the third millennium!

[Pope John Paul II, Message for the 17th World Youth Day]

Beyond Measure

The theme of witness, understood as the founding element of the Christian's life, was at the centre of Pope Francis' reflection during the Mass celebrated at Santa Marta on the morning of Thursday 28 January. But what should characterise this testimony? The Pontiff took the answer directly from the Gospel of the day, quoting the passage from Mark (4:21-25) immediately following the "parable of the seed". After speaking of "the seed that succeeds in bearing fruit" and the one that, instead, falling "into bad soil cannot bear fruit", Jesus "speaks to us of the lamp" that is not placed under the bushel but above the candlestick. It - he explained - "is light and the Gospel of John tells us that the mystery of God is light and that the light came into the world and the darkness did not welcome it". A light, he added, that cannot be hidden, but serves 'to illuminate'.

Here, then, is "one of the traits of the Christian, who has received light in baptism and must give it". The Christian, said the Pope, "is a witness". And precisely the word 'witness' encapsulates 'one of the peculiarities of Christian attitudes'. Indeed: 'a Christian who bears this light, must make it seen because he is a witness'. And if a Christian "prefers not to let God's light be seen and prefers his own darkness", then "he lacks something and is not a complete Christian". A part of him is occupied, darkness 'enters his heart, because he is afraid of the light' and he prefers 'idols'. But the Christian 'is a witness', a witness 'of Jesus Christ, the light of God. And he must put that light on the candelabrum of his life".

The Gospel passage proposed by the liturgy also speaks of "the measure" and reads: "With the measure with which you measure will be measured to you; indeed, more will be given to you". This, Francis said, is "the other peculiarity, the other attitude" typical of the Christian. He referred, in fact, to magnanimity: 'another trait of the Christian is magnanimity, because he is the son of a magnanimous father, with a great soul.

Even when he says: 'Give and it will be given to you', the measure of which Jesus speaks, the Pope explained, is 'full, good, overflowing'. In the same way, 'the Christian heart is magnanimous. It is open, always'. It is not, therefore, 'a heart that closes in its own selfishness'. It is not a heart that sets limits on itself, that 'counts: up to here, up to here'. He continued: 'When you enter into this light of Jesus, when you enter into the friendship of Jesus, when you allow yourself to be guided by the Holy Spirit, the heart becomes open, magnanimous'. A particular dynamic is triggered at that point: the Christian 'does not gain: he loses'. But, in reality, the Pontiff concluded, "he loses in order to gain something else, and with this 'defeat' of interests, he gains Jesus, he gains by becoming a witness to Jesus".

To put his reflection in concrete terms, Francis turned at this point to a group of priests who were celebrating the golden jubilee of their ordination: "fifty years on the road of light and witness" and "trying to be better, trying to bring light to the candelabra"; a light that, it is the experience of all, sometimes "falls", but that it is always good to try to bring back "generously, that is, with a magnanimous heart". And in thanking the priests for all they have done "in the Church, for the Church and for Jesus", and wishing them the "great joy of having sown well, of having enlightened well and of having opened their arms to receive everyone with magnanimity", the Pope also told them: "Only God and your memory know how many people you have received with magnanimity, with the goodness of fathers, of brothers" and "to how many people whose hearts were a little dark, you have given light, the light of Jesus". Because, he concluded, pulling the strings of the argument, "in the memory of a people" remain "the seed, the light of witness, and the magnanimity of love that welcomes".

[Pope Francis, S. Marta homily, in L'Osservatore Romano 29/01/2016]

And quite often we too, beaten by the trials of life, have cried out to the Lord: “Why do you remain silent and do nothing for me?”. Especially when it seems we are sinking, because love or the project in which we had laid great hopes disappears (Pope Francis)

E tante volte anche noi, assaliti dalle prove della vita, abbiamo gridato al Signore: “Perché resti in silenzio e non fai nulla per me?”. Soprattutto quando ci sembra di affondare, perché l’amore o il progetto nel quale avevamo riposto grandi speranze svanisce (Papa Francesco)

The Kingdom of God grows here on earth, in the history of humanity, by virtue of an initial sowing, that is, of a foundation, which comes from God, and of a mysterious work of God himself, which continues to cultivate the Church down the centuries. The scythe of sacrifice is also present in God's action with regard to the Kingdom: the development of the Kingdom cannot be achieved without suffering (John Paul II)

Il Regno di Dio cresce qui sulla terra, nella storia dell’umanità, in virtù di una semina iniziale, cioè di una fondazione, che viene da Dio, e di un misterioso operare di Dio stesso, che continua a coltivare la Chiesa lungo i secoli. Nell’azione di Dio in ordine al Regno è presente anche la falce del sacrificio: lo sviluppo del Regno non si realizza senza sofferenza (Giovanni Paolo II)

For those who first heard Jesus, as for us, the symbol of light evokes the desire for truth and the thirst for the fullness of knowledge which are imprinted deep within every human being. When the light fades or vanishes altogether, we no longer see things as they really are. In the heart of the night we can feel frightened and insecure, and we impatiently await the coming of the light of dawn. Dear young people, it is up to you to be the watchmen of the morning (cf. Is 21:11-12) who announce the coming of the sun who is the Risen Christ! (John Paul II)

Per quanti da principio ascoltarono Gesù, come anche per noi, il simbolo della luce evoca il desiderio di verità e la sete di giungere alla pienezza della conoscenza, impressi nell'intimo di ogni essere umano. Quando la luce va scemando o scompare del tutto, non si riesce più a distinguere la realtà circostante. Nel cuore della notte ci si può sentire intimoriti ed insicuri, e si attende allora con impazienza l'arrivo della luce dell'aurora. Cari giovani, tocca a voi essere le sentinelle del mattino (cfr Is 21, 11-12) che annunciano l'avvento del sole che è Cristo risorto! (Giovanni Paolo II)

Christ compares himself to the sower and explains that the seed is the word (cf. Mk 4: 14); those who hear it, accept it and bear fruit (cf. Mk 4: 20) take part in the Kingdom of God, that is, they live under his lordship. They remain in the world, but are no longer of the world. They bear within them a seed of eternity a principle of transformation [Pope Benedict]

Cristo si paragona al seminatore e spiega che il seme è la Parola (cfr Mc 4,14): coloro che l’ascoltano, l’accolgono e portano frutto (cfr Mc 4,20) fanno parte del Regno di Dio, cioè vivono sotto la sua signoria; rimangono nel mondo, ma non sono più del mondo; portano in sé un germe di eternità, un principio di trasformazione [Papa Benedetto]

In one of his most celebrated sermons, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux “recreates”, as it were, the scene where God and humanity wait for Mary to say “yes”. Turning to her he begs: “[…] Arise, run, open up! Arise with faith, run with your devotion, open up with your consent!” [Pope Benedict]

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.