Priestly prayer involves an exit, an ascent and an entrance. Abraham ascended to the terrible solitude of Mount Moria to sacrifice Isaac. There he was promised and received the lamb caught among the thorns. "Take thy only-begotten son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and go into the land of vision; and there thou shalt offer him as a burnt offering on one of the mountains which I shall point out to thee." (Gen 22.2). The land of vision is, of course, a figuration of the Cross, and the Cross is made present on the altar in the Holy Sacrifice that fulfils the mystery Isaac and the Lamb were aiming at. Every time we ascend to the altar, we ascend Moria, "the land of vision". The priest, acting in persona Christi capitis, is the man who sees. The eyes of a body are in the head. The priest goes to the altar as the head of the body. A simple priest looks at the people gathered before him or around him. The gaze of the priest, the sacerdos, the priest-sacrificer, penetrates beyond the veil, "as if he saw him who is invisible" (Hebrews 11:27).

Moses went out of the camp, ascended the mountain and entered the cloud. An going out, an going up, an going in.

Then when Moses had gone up, the cloud covered the mountain, and the glory of the Lord dwelt on Sinai, covering it with a cloud for six days. On the seventh day then, God called Moses from the midst of the cloud. The appearance of the glory of the Lord was like a blazing fire on the mountaintop, in sight of the children of Israel. And Moses entered into the midst of the cloud, and went up to the top of the mountain, and there he abode forty days and forty nights." (Exodus 24:15-18)

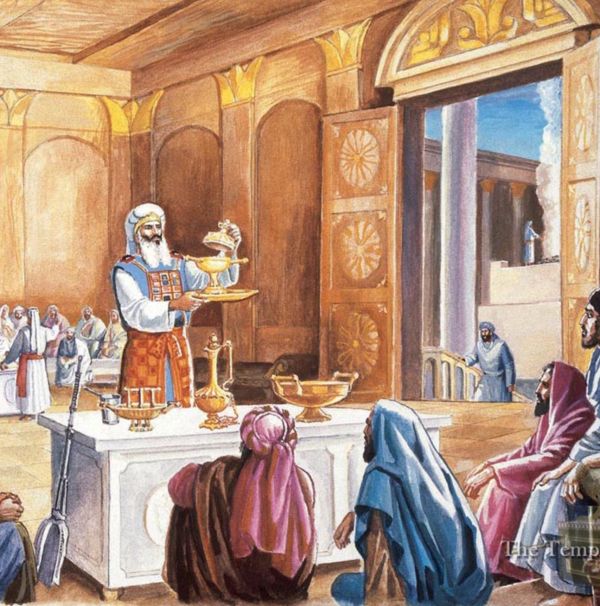

Let us consider the prescriptions laid down in Leviticus for the service of the High Priest on the Day of Atonement. Again, one starts from the congregation of the people of Israel, goes up to the tabernacle and enters.

When the high priest enters the sanctuary to pray for himself and for his house and for the whole community of Israel, no one is to be in the tabernacle until he comes out. (Leviticus 16:17)

In the 17th chapter of St John, there is the same movement. Jesus, while being present to the apostles in the Upper Room, has in a sense already left them to go to the Father. It is, as André Feuillet says, 'poised on the threshold, so to speak, of eternity, halfway between this world and the Father'. This is exactly where we priests stand when we present ourselves at the altar for the Holy Sacrifice. The sacrifice consumed in blood on Calvary had already been accomplished in the Upper Room. And there too there was the going up and the coming in. The essential ritual act of the Day of Atonement is this leaving, this ascending, this entering. "I am no longer in the world, but they are in the world, and I come to you, holy Father" (Jn 17:11).

The triple movement of the Fourth Gospel of separating, ascending and entering has its parallel in St Luke's account of the infant Jesus ascending to Jerusalem, separating from his mother and St Joseph for three days and entering the temple where he takes his place "in the midst of the doctors" (Luke 2:46). St Luke, in his narration, expresses the very mystery of which Jesus speaks in the Johannine priestly prayer: "I am no longer in the world, but they are in the world, and I am coming to you". "But he asked them, 'What reason had ye to seek me? Did you not know that I must be in the place that belongs to my Father?" (Luke 2:49).

The work of redemption is fully realised not by the Incarnation alone, nor by Jesus' hidden life, nor by his teaching, nor by the signs given during his public ministry, nor by his passion and death, but by his return to the Father in the mystery of his glorification. Father, the hour has come for your Son to glorify you" (John 17:1).

Jesus, by departing, ascending, and entering "into the place that belongs to his Father," accomplishes what the entrance of the high priest into the Holy of Holies on the Day of Atonement is a figure and type of. The entry of the high priest into the Holy of Holies was the crucial culmination of the rite of atonement. I would like to suggest that in the priesthood of the Old Dispensation, in the priesthood of Christ and in our priesthood there is - dare I say it - a terrible loneliness. The priest's mediation and the effectiveness of his intercession are, in fact, conditioned by his solitude. Nowhere has the priesthood of the atoning High Priest been more perfectly expressed than in the total and terrible solitude of the Holy of Holies. Nowhere is the priesthood of Christ more perfectly expressed than in the total and terrible solitude of the Cross. Nowhere is our priesthood more perfectly expressed than in the total and terrible solitude of the altar. It must be so, because just as the loneliness of the high priest pointed to the loneliness of the crucified Jesus "lifted up from the earth" (Jn 12:32), so too our loneliness at the altar refers to and derives from the loneliness of the Cross.Allow me to dwell for a moment on the enormous significance of this ritual of priestly solitude. Most of us, I believe, have ambivalent feelings about solitude. All of us, if we are honest, fear solitude and try to escape it. It was not so long ago that, on a certain day while standing at the altar for the canon of the Mass, I was seized with an overwhelming awareness of my solitude. It was not an emotional loneliness, not a lack, but a breaking into something absolutely and essentially priestly. It has to do with the Johannine model of separating, ascending and entering a place where, like the high priest of old and like Jesus on the cross, I found myself alone before God. At that moment I realised that this priestly solitude is, in some way and by divine design, the condition of my mediation, the ground of my intercession.

Pius Parsch - some of you, as old as I am or older, will remember reading The Church's Year of Grace in the Seminary - linked the loneliness of the priest at the altar with the solemn silence of the then-canon, he says:

This complete silence is the most effective expression of the adoration and reverence due to God who comes to us in the mystery of the Mass. The priest ordained by God, like Moses, enters alone into the clouds that cover the mountain of God.

Even Josef Jungman, the great Jesuit liturgist, in his monumental Missarum Solemnia, speaks of the solitude of the priest at the altar in continuity with that of the Jewish high priest in the Holy of Holies:

The priest enters the sanctuary of the Canon alone. 'Hitherto the people crowded around him, their songs sometimes accompanying him. But the chants became less frequent and, after the steep climb of the Great Prayer, ended in the triple Sanctus. A holy stillness reigns; silence is a worthy preparation for God's approach. Like the Old Testament high priest, who once a year was allowed to enter the Holy of Holies with the blood of a sacrificial animal (Hebrews 9:7), the priest now separates himself from the people and goes to the almighty God to offer the sacrifice to Him.

Allow me to take this a step further. It seems to me that this ritual priestly solitude at the altar is what redeems and gives value to all the loneliness of a priest's life: to the loneliness of coming home to an empty flat; to the longing for companionship that, at certain hours, is like a dull, unrelenting ache; to the isolation of feeling misunderstood, unappreciated and, at times, especially in today's Ireland, unnecessary and unwanted.

In the 19th chapter of St. John, the account of Jesus' crucifixion and death, we see, as in a mystical icon written by the Holy Spirit, the prophecy of John 12:31: "And I, if I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all to myself. This he said, pointing to the death he was to suffer (Jn 12:31). The exit: He was crucified outside the city walls. The ascent: it is the entire Way of the Cross culminating in the crucifixion. The entrance: it is the terrible loneliness of Jesus - "Eli, Eli, lamma sabacthani?", i.e. "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" (Matt 27:46) -, the terrible loneliness of Jesus. (Mt 27:46) - the cry at the moment of penetrating the veil - "And Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said: Father, into your hands I commend my spirit. And saying this, he yielded up the spirit' (Luke 23:46) - and the proof is this: 'And behold, the veil of the temple was rent in two from top to bottom' (Matthew 27:51).

+ Giovanni D’Ercole