Old Testament Tradition and the New Meaning of Purity

1. An indispensable complement to the words pronounced by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount on which we have centred the cycle of our present reflections must be the analysis of purity. When Christ, in explaining the proper meaning of the commandment "Thou shalt not commit adultery", made reference to the inner man, he specified at the same time the fundamental dimension of purity, with which the mutual relations between man and woman in and out of marriage are to be marked. The words: 'But I say to you, whoever looks at a woman to lust after her has already committed adultery with her in his heart' (Mt 5:27-28) express what is contrary to purity. At the same time, these words demand the purity that in the Sermon on the Mount is included in the statement of the beatitudes: "Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God" (Mt 5:8). In this way Christ addresses an appeal to the human heart: he invites it, not accuses it, as we have already made clear above.

2. Christ sees in the heart, in man's innermost being, the source of purity - but also of moral impurity - in the fundamental and most generic meaning of the word. This is confirmed, for example, by his reply to the Pharisees, scandalised by the fact that his disciples "transgress the tradition of the ancients, for they do not wash their hands when they take food" (Mt 15:2). Jesus then said to those present: "Not what goes into the mouth makes a man unclean, but what comes out of the mouth makes a man unclean" (Mt 15:11). To his disciples, however, answering Peter's question, he explained these words thus: "...what comes out of the mouth comes from the heart. This makes a man unclean. For from the heart come evil intentions, murders, adulteries, prostitutions, thefts, false witness, blasphemies. These are the things that make a man unclean, but eating without washing one's hands does not make a man unclean" (cf. Mt 15:18-20; cf. Mk 7:20-23).

When we say "purity", "pure", in the first meaning of these terms, we indicate that which contrasts with uncleanness. 'Soiling' means 'make unclean', 'pollute'. This refers to the different spheres of the physical world. We speak, for example, of a 'dirty street', a 'dirty room', we also speak of 'polluted air'. Likewise, man can also be 'unclean' when his body is not clean. To remove the filthiness of the body, it must be washed. In the Old Testament tradition, great importance was attached to ritual ablutions, e.g. washing one's hands before eating, which is mentioned in the quoted text. Numerous and detailed prescriptions concerned the ablutions of the body in relation to sexual impurity, understood in an exclusively physiological sense, which we mentioned earlier (cf. Lev 15 ). According to the state of medical science at the time, the various ablutions could correspond to hygienic prescriptions. Insofar as they were imposed in the name of God and contained in the Sacred Books of the Old Covenant legislation, the observance of them acquired, indirectly, a religious significance; they were ritual ablutions and, in the life of the man of the Old Covenant, they served ritual "purity".

3. In relation to the aforementioned legal-religious tradition of the Old Covenant, an erroneous way of understanding moral purity(1) was formed. It was often understood in an exclusively outward and 'material' manner. In any case, there was an explicit tendency towards such an interpretation. Christ radically opposes it: nothing makes man unclean "from the outside", no "material" filthiness makes man impure in a moral, that is to say, inner sense. No ablution, not even ritual, is suitable in itself to produce moral purity. This has its exclusive source within man: it comes from the heart. It is probable that the respective Old Testament prescriptions (those, for example, found in Leviticus) (Lev 15:16-24; 18:1ff; 12:1-5) served not only for hygienic purposes, but also to attribute a certain dimension of interiority to what is corporeal and sexual in the human person. In any case, Christ was very careful not to link purity in the moral (ethical) sense with physiology and related organic processes. In the light of the words of Matthew 15:18-20, quoted above, none of the aspects of sexual "uncleanness", in the strictly somatic, biophysiological sense, enters per se into the definition of purity or impurity in the moral (ethical) sense.

4. The above statement ( Mt 15:18-20 ) is especially important for semantic reasons. In speaking of purity in the moral sense, i.e. the virtue of purity, we make use of an analogy, according to which moral evil is compared precisely to uncleanness. Certainly, this analogy has been part of the sphere of ethical concepts since the earliest times. Christ takes it up and confirms it in its full extent: 'What comes out of the mouth comes from the heart. This makes a man unclean'. Here Christ speaks of every moral evil, every sin, i.e. transgressions of the various commandments, and enumerates "evil intentions, murders, adulteries, prostitutions, thefts, false witness, blasphemies", without limiting himself to a specific kind of sin. It follows that the concept of 'purity' and 'impurity' in the moral sense is first and foremost a general concept, not a specific one: hence every moral good is a manifestation of purity, and every moral evil is a manifestation of impurity. The statement in Matthew 15:18-20 does not restrict purity to a single area of morality, i.e. to that connected with the commandment 'Thou shalt not commit adultery' and 'Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife', i.e. to that which concerns the mutual relations between man and woman, linked to the body and its concupiscence. Similarly, we can also understand the beatitude of the Sermon on the Mount, addressed to men who are 'pure in heart', both in a generic and more specific sense. Only the eventual contexts will allow us to delimit and specify this meaning.

5. The broader and more general meaning of purity is also present in the letters of St Paul, in which we shall gradually identify the contexts that explicitly restrict the meaning of purity to the "somatic" and "sexual" sphere, i.e. to that meaning that we can grasp from the words pronounced by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount on concupiscence, which is already expressed in "looking at the woman", and is equated with "adultery committed in the heart" (cf. Mt 5:27-28 ).

St Paul is not the author of the words on triple concupiscence. They are, as we know, found in the first letter of John. It can, however, be said that analogous to what for John ( 1 Jn 2:16-17 ) is the opposition within man between God and the world (between what comes "from the Father" and what comes "from the world") - an opposition that arises in the heart and penetrates into the actions of man as "concupiscence of the eyes, concupiscence of the flesh and pride of life" - St Paul notes another contradiction in the Christian: the opposition and at the same time the tension between the "flesh" and the "Spirit" (written with a capital letter, i.e. the Holy Spirit): "I say to you therefore, walk according to the Spirit, and you will not be led to satisfy the desires of the flesh; for the flesh has desires contrary to the Spirit, and the Spirit has desires contrary to the flesh; these things are opposed to each other, so that you do not do what you would" ( Gal 5:16-17 ). It follows that life 'according to the flesh' is in opposition to life 'according to the Spirit'. "For those who live according to the flesh, think about the things of the flesh; but those who live according to the Spirit, about the things of the Spirit" ( Rom 8:5 ).

In the following analyses we will try to show that purity - the purity of heart, of which Christ spoke in the Sermon on the Mount - is properly realised in life "according to the Spirit".

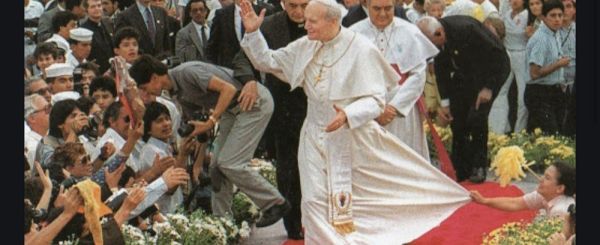

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 10 December 1980]