don Giuseppe Nespeca

Giuseppe Nespeca è architetto e sacerdote. Cultore della Sacra scrittura è autore della raccolta "Due Fuochi due Vie - Religione e Fede, Vangeli e Tao"; coautore del libro "Dialogo e Solstizio".

In that gesture and in those words is the whole story of salvation

Dear brothers and sisters!

[...] in his public life Jesus healed many sick people, revealing that God wants life for human beings, life in its fullness. This Gospel (Mk 1:40-45) shows us Jesus in touch with a form of disease then considered the most serious, so serious as to make the person infected with it “unclean” and to exclude that person from social relations: we are speaking of leprosy. Special legislation (cf. Lev 13-14) allocated to priests the task of declaring a person to be “leprous”, that is, unclean; and it was likewise the priest’s task to note the person’s recovery and to readmit him or her, when restored to health, to normal life.

While Jesus was going about the villages of Galilee preaching, a leper came up and besought him: “If you will, you can make me clean”. Jesus did not shun contact with that man; on the contrary, impelled by deep participation in his condition, he stretched out his hand and touched the man — overcoming the legal prohibition — and said to him: “I will; be clean”.

That gesture and those words of Christ contain the whole history of salvation, they embody God’s will to heal us, to purify us from the illness that disfigures us and ruins our relationships. In that contact between Jesus’ hand and the leper, every barrier between God and human impurity, between the Sacred and its opposite, was pulled down. This was not of course in order to deny evil and its negative power, but to demonstrate that God’s love is stronger than all illness, even in its most contagious and horrible form. Jesus took upon himself our infirmities, he made himself “a leper” so that we might be cleansed.

A splendid existential comment on this Gospel is the well known experience of St Francis of Assisi, which he sums up at the beginning of his Testament: “This is how the Lord gave me, Brother Francis, the power to do penance. When I was in sin the sight of lepers was too bitter for me. And the Lord himself led me among them, and I pitied and helped them. And when I left them I discovered that what had seemed bitter to me was changed into sweetness in my soul and body. And shortly afterward I rose and left the world” (FF, 110).

In those lepers whom Francis met when he was still “in sin” — as he says — Jesus was present; and when Francis approached one of them, overcoming his own disgust, he embraced him, Jesus healed him from his “leprosy”, namely, from his pride, and converted him to love of God. This is Christ’s victory which is our profound healing and our resurrection to new life!

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 12 February 2012]

To those suffering from leprosy

My beloved brothers and sisters in Jesus Christ,

Your presence arouses in me tenderness and compassion, some of the feelings that Jesus Christ felt when he received the sick. He bent over human suffering, over the wounds of the body, and revived serenity, confidence and courage in people's hearts. I would like this visit to have the same spiritual effect; and I would like to have more time to talk to each one, because I love you very much, I suffer seeing you suffer and I want to comfort you all.

And why do I love you? Because you are human persons, loved by God, and by his son Jesus Christ, who suffered so much for you, because the Catholic Church, like Jesus Christ, loves you and will do all it can for you.

I am leaving; but I ask Monsignor Bishop - who is your great friend and to whom this work of Cumura is due - and the doctors, nurses and all those who assist you, that they do you all the good that the Pope would wish you if he could remain here with you. And I leave you, as a reminder, the message that, from here and now, I address to the whole Church, with an appeal on your behalf.

Do not let yourselves be defeated! Suffering always has value. It can teach the world what love like the love of Jesus means. And may this life of yours serve to help your neighbour, to receive and transmit moral strength; and, if you are Christian, may you transmit the power of renewal and the joy of Christ. He rose from the dead so that all might have access to eternal life. Your suffering can make the world a better place, if you are friends of God and friends of each other, if you unite serenity, confidence and courage with the progress of medicine and the goodwill of those who care for you with love.

I will never forget you and I trust in your friendly remembrance. I will pray for you and rely on your prayers. I impart to you with all my heart the Apostolic Blessing.

[Pope John Paul II, Leprosarium in Cumura, Guinea Bissau, 28 January 1990]

Compassion: "suffering-with-another"

[...] The evangelist Mark is telling us of Jesus' action against all kinds of evil, for the benefit of those who suffer in body and spirit: the possessed, the sick, sinners... He presents himself as the one who fights and overcomes evil wherever he encounters it. In today's Gospel (cf. Mk 1:40-45) this fight of His confronts an emblematic case, because the sick person is a leper. Leprosy is a contagious and merciless disease, which disfigures the person, and was a symbol of impurity: the leper had to stay out of built-up areas and signal his presence to passers-by. He was marginalised by the civil and religious community. He was like the walking dead.

The episode of the healing of the leper unfolds in three short passages: the invocation of the sick person, Jesus' response, and the consequences of the prodigious healing. The leper begs Jesus "on his knees" and says to him: "If you wish, you can cleanse me" (v. 40). To this humble and trusting prayer, Jesus reacts with a profound attitude of his soul: compassion. And 'compassion' is a very profound word: compassion that means 'suffering-with-another'. Christ's heart manifests God's paternal compassion for that man by approaching him and touching him. And this detail is very important. Jesus "stretched out his hand and touched him ... and immediately the leprosy disappeared from him and he was cleansed" (v. 41). God's mercy overcomes all barriers and Jesus' hand touches the leper. He does not place himself at a safe distance and does not act by proxy, but exposes himself directly to the contagion of our evil; and so it is precisely our evil that becomes the place of contact: He, Jesus, takes from us our sick humanity and we take from him his healthy and healing humanity. This happens every time we receive a Sacrament with faith: the Lord Jesus 'touches' us and gives us his grace. Here we think especially of the Sacrament of Reconciliation, which heals us from the leprosy of sin.

Once again, the Gospel shows us what God does in the face of our evil: God does not come to "lecture" us on pain; neither does he come to eliminate suffering and death from the world; rather, he comes to take upon himself the weight of our human condition, to carry it to the end, to free us radically and definitively. This is how Christ fights the evils and sufferings of the world: by taking them upon himself and overcoming them with the power of God's mercy.

To us, today, the Gospel of the healing of the leper tells us that, if we want to be true disciples of Jesus, we are called to become, united with him, instruments of his merciful love, overcoming all kinds of marginalisation. To be "imitators of Christ" (cf. 1 Cor 11:1) when faced with a poor person or a sick person, we must not be afraid to look them in the eye and approach them with tenderness and compassion, and to touch and embrace them. I have often asked people who help others to do so by looking them in the eye, not to be afraid to touch them; that the gesture of helping is also a gesture of communication: we too need to be welcomed by them. A gesture of tenderness, a gesture of compassion... But I ask you: when you help others, do you look them in the eye? Do you welcome them without fear of touching them? Do you welcome them with tenderness? Think about this: how do you help? At a distance or with tenderness, with closeness? If evil is contagious, so is good. Therefore, good must abound in us, more and more. Let us be infected by the good and let us infect the good!

[Pope Francis, Angelus 15 February 2015]

Behold the Lamb: Tenderness without neurosis. Selfishness without downgrades

The liberated mother-in-law and her path

New life-wave

(Mk 1:29-39)

The Lord does not admit the misunderstanding of a faith that reduces him to the same level as acclaimed santons and healers (vv.34b.36-38).

Too many seek him just for this, even the closest followers (vv.29.36b), but the Son of God prevents his intimates the popular chatter [alway on the prowl] hunting for the extraordinary (vv.34b.37).

It is adherence to his lifestyle that helps to recover (vv.30-34a).

For evangelized people who become announcers, keeping oneself upright is linked to an evolving Faith, therefore to an attitude of renewal (vv.38-39).

Already in the synagogue the Lord had stirred the waters of quietism.

So He doesn’t miss the opportunity to "touch" a woman [at that time, a non-person] and make himself legally impure through direct contact with the sick.

Moreover, no rabbi would ever let himself be served by a woman.

In short, Jesus puts into question not only theology, but upset the assumptions of human and spiritual relationships.

Only ‘service’ counts, in all the ancient conception considered unworthy thing for a perfect development of the personality.

Especially in the classical mentality, characteristic of the human being was the domination and the estrangement to every sense of neighbour.

Then, in this upheaval, the disciples' idea to talk directly to Jesus about the difficulties they cannot provide for is excellent (v.30b).

Faced with problems, imbalances, needs of one's own and others - before rushing to come up with rough solutions - addressing the Lord is the most sensible choice to make, for a basic healing.

Non-life presuppositions make us prisoners, unable to move towards God and the brothers.

In Christ we are called to introduce the blockages of those who are narrowed by difficulties, into a new condition.

The suffocated energy bubble that compresses us characterizes humanity even of the past, and re-proposes itself.

In short, the attendance of places of prayer (v.29) must lead us - like Jesus - to ignore some laws of purity, if dehumanizing.

Non-negotiable principle of the Gospels is the real good of concrete women and men, as they are and where they are.

While succeeding, we will reject the temptation to success (v.35).

Last note on Mk’s brushstroke about the story of Peter’s mother-in-law, who finds her unexpressed virtues thanks to contact with the person of the Lord.

Icon of a still narrowing mental model, which stifles the youth of being and doing.

In the soul of the ancient people, the disregarded, stifled, denied, unused talents had become hardships.

Now Christ the Present cares for such "inflammations". We are no longer made ‘mute’ and ‘dependent’ on the situation or inherited mentality.

And «relieved» in caring for oneself and others, the return to fluid life becomes easy, even with minimal gestures.

The intimately taut or suffocated resources - that appealed us with tightness in the chest - surface, and dilate also in favour of others.

The "mother-in-law" once lying down, breathes and overcomes ageing. She rediscovers and expresses her skills.

This is the healing action of Jesus, all at the gates of each one.

[Wednesday 1st wk. in O.T. January 14, 2026]

In difficult choices, there is prayer. New wave of life

The liberated mother-in-law and her journey (female)

(Mk 1:29-39)

"The essential thing is to listen to what rises from within. Our actions are often nothing more than imitation, hypothetical duty or misrepresentation of what a human being should be. But the only true certainty that touches our lives and our actions can only come from the springs that gush deep within ourselves. One is at home under the sky, one is at home anywhere on this earth if one carries everything within oneself. I have often felt, and still feel, like a ship that has taken on board a precious cargo: the ropes are cut and now the ship goes, free to sail everywhere".

(Etty Hillesum, Diary)

The Lord does not allow the misunderstanding of a faith that vulgarises Him. Jesus is not an all-intimate counsellor, nor a practitioner without Mystery.

Christ is not a miracle-worker - a freak - handcuffed in the manner of acclaimed holy men and healers (vv.34b.36-38).

Too many seek him out because of this, even his closest followers (vv.29.36b), but the Son of God prevents popular chatter, always chasing the extraordinary (vv.34b.37).

It is adherence to his way of life that helps one to rise up (vv.30-34a).

For the evangelised who become proclaimers, keeping up is linked to an evolving Faith, hence to the attitude of restarting (vv.38-39).

But on the Sabbath it was even forbidden to visit and care for the sick.

Already in the synagogue, the Lord had stirred the fetid waters of quietism.

Here he did not miss the opportunity to 'touch' a woman (at that time, a non-person) and make himself legally impure through direct contact with the sick woman.

Then, no rabbi would ever let himself be served by a woman.

Jesus challenges not only post-liturgical theology and purism, but upsets the assumptions of human and spiritual relationships.

Only 'service' counts, in all ancient conception considered unworthy for a perfect development of the personality.

[Even more so for the propagandistic expansion of archaic religions - armed with all their antiquated baggage, which only made souls sick].

Above all, in the ancient and classical mentality, characteristic of the human being was dominance, a sense of individual strength and clan or nation; alienation from all sense of neighbour.

So, in such a turnaround, the disciples' idea of speaking directly to Jesus about the difficulty they do not know how to deal with is excellent (v.30).

In the face of garbles, imbalances, their own and other people's needs - before rushing to bungle sloppy solutions - turning to the Lord is the most sensible choice to make, for fundamental healing.

Assumptions of non-life make us prisoners, unable to move towards God and our brothers and sisters.

In Christ we are called to bring the blocks of those who are restricted by difficulties into a new condition.

The bubble of stifled energy that compresses us characterises the humanity of the past too, and it recurs (v.31b).

Attending places of prayer must lead us - like Jesus - to ignore certain laws of purity; even to transgress the abstract norm of religion, if it dehumanises.

The only non-negotiable principle is the real good of the concrete woman and man, as they are and where they are; in their integrity.

We only honour God - like Christ - by valuing the excesses or absorbing the 'impurities' of sisters and brothers, in order to restore their dignity and motivation.

And while succeeding, we reject the temptation of success (v.35).

More important than being acclaimed is to continue the work of Announcement and Benevolence, without hesitation. Even in remote places.

One must not be deceived by the appearances of the urban and central apostolate that is always well organised.

One must flee both legalism and bungling enthusiasm, to go and find a new geography, and people where they are.

The Gospel requires an itinerant commitment, full of surprises.

This applies to the ecclesial bureaucracy itself, which sometimes unfortunately continues to stall many genuine pastoral initiatives, willingly hijacking them.

In difficult choices, prayer (v.35) becomes a bridge connecting life with our sacred centre, where God himself dwells and expresses himself - guiding us in a superior way.

Precisely, the Son prays because the followers seem exalted by success.

They allow themselves to be carried away by external passion and self-love, instead of evaluating with deep instinct and reason.

At this rate, they would lose their ability to succour infirmities of all kinds.

In fact, it was precisely the leaders "set out on his trail" - like "Pharaoh" and his militia (Ex 14:8-9) to prevent the Exodus (cf. Mk 1:38) to another land.

That of Jesus being forced to flee from the clutches of his own who want to take him hostage in order to live by reflected light and be revered by the crowds, is unfortunately still a story of our times - to be eradicated without much ado.

It is no coincidence that the Lord leads the disciples to involve themselves "preaching in their synagogues throughout Galilee and casting out demons" (v.39).

As if the dark powers that had been annihilating the people since then were lurking in the very places of ancient worship and the official religious institution.

The liberated mother-in-law and her (female) path

A final note on Mk's brushstroke on the story of Peter's mother-in-law, a "woman" who rediscovers her unexpressed capacities through contact with the person of the Lord.

An icon of a mental model that is still narrow, that stifles the youth of being and doing.

Ancient figure, of a tradition (of inherited religiosity) that holds back the intimate resources of the people [in Hebrew Israèl is female].

A world of restraints that make one uncomfortable, because of stifled, compressed energies - before Christ disappeared. To the point of not realising they are still inside.

I imagine precisely that such an old woman who literally 'resurrects' can be reinterpreted with spiritual fruit, for the journey of us all.

The Lord frees; he heals "inflammations". He gives greater joy of life.

He imparts an elixir of youth - especially when we feel held as dependents or slaves, without space.

Stuck and rendered dumb by the transmitted culture or situation, not only of health.

"And they came out of the synagogue into the house of Simon and Andrew together with James and John. Now Simon's mother-in-law lay feverish, and they told him about her. And approaching him he made her stand up by taking his hand. And the fever left her and served them" (vv.29-31).

There are revealing symptoms of discomfort: e.g. a life - even a spiritual one - that does not fit... because it denies abilities, constrains them, keeps them in a corner, does not allow them to be used.

To the point of no longer knowing what they are.

Here come symptoms that lie us down: anxious, mortifying, and feelings of constriction and dependence.

One would perhaps like to do something different, but then there are fears, tightness in the chest that close the horizon and make one tense, (even at that time) uncomfortable, stressed, blocked.

In the soul of the ancient people, talents disregarded, denied, unused had become hardships.

Now in Christ Present, the return to the fluid life, as well as the care of self and others, becomes easy, with minimal gestures.

The abilities that made intimate appeal, surface, and dilate in favour of others.

Relieved, the 'mother-in-law' breathes and overcomes ageing.

Before, sadness perhaps appeared, because the desire for a new birth was stifled by the many chores to be done or other cravings (fevers) that plant us there and do not restart feelings.

We know, however, that life restarts the moment someone helps to heal the sharp actions ["hand" constricted: Mt 8:15; Mk 1:31] and widen our gaze towards what is conversely blossoming in us.

By shifting perception from what nags us (torments and hinders) to what arises more spontaneously and is finally and unexpectedly valued, the blocks of tender, fresh energy disappear.

Then the garb of the ancient role is laid aside and we no longer give up expressing ourselves.

Also - for us - without closing ourselves off in the usual environment and way of doing things, which intimately do not belong to us.

Whoever gives the other a proper space draws on the virtues of our inner, evergreen primordial states - and opens up those of all.

All for a growth that does not only correspond to a precipitous elevation, but rather to a better grounding in the being of people.

By hibernating the burden of duties or models that do not correspond, life is renewed.

We realise that we are as if inhabited by the divine Gold that wants to surface and express itself with breadth, instead of remaining tense and controlled.

This is the healing action of Jesus, all at everyone's doorstep.

In fact, another great novelty of the new Rabbi's proposal - which was spreading - was the acceptance of women as we would say today "deaconesses" [v.31 cf. Greek verb] of the Church. Here in the figure of the House of Peter: "of Simon and Andrew, together with James and John" (v.29).

This was what had been happening since the middle of the first century (cf. Rom 16:1) and still has much to teach us.

With God, one cannot get used to (multi)secular formalities emptied of life.

But religious traditions resisted the onslaught of the Faith-Love experience: even in the mid-1970s, communities did not feel free to gather those in need of care until the evening (v.32).

It was indeed a Sabbath day - and after leaving the synagogue. The same impediment and delay is described in the episode of the Magdalene at the tomb on Easter morning.

Cultural heritage and religious conformity remained a great burden for the experience of the personal Saviour Christ.

Customs still remained a snare for the complete discovery of the power of full Life contained in the new total and creative proposal of "il Monte".

The Tao writes (xxviii):

"He who knows he is male, and keeps himself female, is the strength of the world; being the strength of the world, virtue never separates itself from him, and he returns to being a child. He who knows himself to be white, and keeps himself dark, is the model of the world; being the model of the world, virtue never departs from him; and he returns to infinity. He who knows himself to be glorious, and maintains himself in ignominy, is the valley of the world; being the valley of the world, virtue always abides in him; and he returns to being crude [genuine, not artificial]. When that which is crude is cut off, then they make instruments of it; when the holy man uses it, then he makes them the first among ministers. For this the great government does no harm'.

Master Wang Pi comments thus:

"That of the male is here the category of those who precede, that of the female is the category of those who follow. He who knows that he is first in the world must put himself last: that is why the saint postpones his person and his person is premised. A gorge among the mountains does not seek out creatures, but these of themselves turn to it. The child does not avail itself of wisdom, but adapts itself to the wisdom of spontaneity".

In the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas we read in Nos. 22-23:

"Jesus saw little ones taking milk.

And he said to his disciples:

"These little sucklings resemble those

Who are entering the Kingdom.

They asked him:

"If we are like those babies, will we enter the Kingdom?"

Jesus answered them:

"When you make two things one and make

The inner equal to the outer and the outer equal to the inner

And the superior equal to the inferior,

When you reduce the male and the female to one being

So that the male is not only male

And the female does not remain only female,

When you consider two eyes as a unit of eye

But one hand as a unit of hand

And one foot as a unit of foot,

A vital function in place of a vital function

Then you will find the entrance to the Kingdom".

"Jesus said:

"I will choose you one from a thousand and two from ten thousand.

And these shall be found to be one individual'".

To internalise and live the message:

How has the Encounter with the Lord and His personal Touch healed you, made you young and whole?

True Physician

Dear brothers and sisters

Today's Gospel (cf. Mk 1:29-39) [...] presents to us Jesus who, after preaching on the Sabbath in the synagogue of Capernaum, heals many sick people, beginning with Simon's mother-in-law. Upon entering Simon's house, he finds her lying in bed with a fever and, by taking her hand, immediately heals her and has her get up. After sunset, he heals a multitude of people afflicted with ailments of every kind. The experience of healing the sick occupied a large part of Christ's public mission and invites us once again to reflect on the meaning and value of illness, in every human situation. This opportunity is also offered to us by the World Day of the Sick which we shall be celebrating next Wednesday, 11 February, the liturgical Memorial of Our Lady of Lourdes.

Despite the fact that illness is part of human experience, we do not succeed in becoming accustomed to it, not only because it is sometimes truly burdensome and grave, but also essentially because we are made for life, for a full life. Our "internal instinct" rightly makes us think of God as fullness of life indeed, as eternal and perfect Life. When we are tried by evil and our prayers seem to be in vain, then doubt besets us and we ask ourselves in anguish: what is God's will? We find the answer to this very question in the Gospel. For example, in today's passage we read that Jesus "healed many who were sick with various diseases, and cast out many demons" (Mk 1: 34); in another passage from St Matthew it says that Jesus "went about all Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and preaching the Gospel of the Kingdom and healing every disease and every infirmity among the people" (Mt 4: 23). Jesus leaves no room for doubt: God whose Face he himself revealed is the God of life, who frees us from every evil. The signs of his power of love are the healings he performed. He thus shows that the Kingdom of God is close at hand by restoring men and women to their full spiritual and physical integrity. I maintain that these cures are signs: they are not complete in themselves but guide us towards Christ's message, they guide us towards God and make us understand that man's truest and deepest illness is the absence of God, who is the source of truth and love. Only reconciliation with God can give us true healing, true life, because a life without love and without truth would not be life. The Kingdom of God is precisely the presence of truth and love and thus is healing in the depths of our being. One therefore understands why his preaching and the cures he works always go together: in fact, they form one message of hope and salvation.

Thanks to the action of the Holy Spirit, Jesus' work is extended in the Church's mission. Through the sacraments it is Christ who communicates his life to multitudes of brothers and sisters, while he heals and comforts innumerable sick people through the many activities of health-care assistance that Christian communities promote with fraternal charity. Thus they reveal the true Face of God, his love. It is true: very many Christians around the world priests, religious and lay people - have lent and continue to lend their hands, eyes and hearts to Christ, true physician of bodies and souls! Let us pray for all sick people, especially those who are most seriously ill, who can in no way provide for themselves but depend entirely on the care of others. May each one of them experience, in the solicitude of those who are beside them, the power and love of God and the richness of his saving grace. Mary, health of the sick, pray for us!

[Pope Benedict, Angelus 8 February 2009]

Capernaum Day

1. "Woe to me if I did not preach the gospel" (1 Cor 9:16).

These words were written by Saint Paul the Apostle in his first letter to the Corinthians.

These words echo strongly in different epochs, among different generations of the Church.

In our times they were heard, particularly strongly, during the Synod of Bishops in 1974 on the topic of evangelisation. The theme arose from the vast substratum of the teaching of the Second Vatican Council and the rich soil of the Church's experience in the contemporary world. The fruit of the work of that Synod was passed on by the participating bishops to Pope Paul VI, and found its expression in the splendid apostolic exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi.

"Woe to me if I did not preach the Gospel," says Saint Paul. And he adds: 'For it is not a boast for me to preach the Gospel; it is a duty for me' (1 Cor 9:15)... I only fulfil the duties of a minister!

And so: not for boasting, but also not for reward!

Indeed, the reward is the very fact that I can preach the gospel without any reward.

And then he writes: "For although I was free from all, I made myself the servant of all" (1 Cor 9:19).

It would be difficult to find words, which could say more: to preach the Gospel is to become "a servant of all in order to gain the greatest number" (1Cor 9:19). And developing the same idea, he adds: "I have made myself weak with the weak in order to gain the weak; I have made myself all things to all men, in order to save someone at any cost. I do everything for the sake of the Gospel, to become a sharer with them" (1Cor 9:22-23).

The theme we are invited to meditate on at today's meeting is therefore evangelisation.

2. Paul VI's apostolic exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi reminds us that the first evangeliser is Christ himself.

Let us look in the light of today's liturgical pericope at what a day (and night) of Christ's evangelising activity looks like.

We find ourselves in Capernaum.

Christ leaves the synagogue and, together with James and John, goes to the house of Simon and Andrew. There he heals Simon's mother-in-law (Peter), so that she can immediately get up and serve them.

After the setting of the sun, "all the sick and the possessed are brought to Christ. The whole city was gathered before the gate" (Mk 1:32-33). Jesus does not speak, but performs the healing: "He healed many who were afflicted with various diseases and cast out many demons". At the same time, a significant remark: "he did not allow the demons to speak, because they knew him" (Mk 1:34).

Perhaps all this went on until late in the evening.

Early in the morning Jesus is already praying.

Simon comes with his companions, to tell him: "Everyone is looking for you" (Mk 1:37).

But Jesus replies: "Let us go elsewhere to the neighbouring villages so that I may preach there also; for this is why I have come" (Mk 1:38).

We read later: "And he went throughout all Galilee, preaching in their synagogues and casting out demons" (Mk 1:39).

3. In summary, based on that day, spent in Capernaum, it can be said that the evangelisation conducted by Christ himself consists of teaching about the kingdom of God and serving the suffering.

Jesus performed signs, and all of these formed the whole of a Sign. In this Sign, the sons and daughters of the people, who had come to know the image of the Messiah, described by the prophets and especially by Isaiah, can discover without difficulty that "the kingdom of God is at hand": he is the one who "has taken upon himself our sufferings, he has borne our sorrows" (Is 53:4).

Jesus does not only preach the Gospel as they all did after him, e.g. the wonderful Paul, whose words we meditated on just now. Jesus is the Gospel!

A great chapter in his messianic service is addressed to all categories of human suffering: spiritual and physical.

It is not without reason that we also read today a passage from the book of Job, which illustrates the dimension of human suffering: "If I lie down, I say: When shall I rise? / The shadows are lengthening, and I am weary to toss and turn until dawn" (Job 7:4).

We know that Job, passing through the abyss of suffering, has reached the hope of the Messiah.

The psalmist speaks of this Messiah in the words of today's liturgy: 'The Lord rebuilds Jerusalem, / gathers the lost of Israel, / he mends the brokenhearted / and binds up their wounds ... / The Lord upholds the humble / but he brings down to the ground the wicked" (Ps 147 [146]:2.3.6).

This is precisely the Christ.

And this is precisely the Gospel.

Paul of Tarsus, who was one of the greatest proclaimers of the Gospel and knows its history, is fully aware that he shares in it: "All things I do for the sake of the Gospel, that I may be partakers of it" (1 Cor 9:23).

[Pope John Paul II, homily 7 February 1982]

Announce and Heal. Action of the Church

Today’s Gospel (cf. Mk 1:29-39) presents us Jesus who, after having preached in the Synagogue on the Sabbath, heals many sick people. Preaching and healing: this was Jesus’ principle activity in his public ministry. With his preaching he proclaims the Kingdom of God, and with his healing he shows that it is near, that the Kingdom of God is in our midst.

Entering the house of Simon Peter, Jesus sees that his mother-in-law is in bed with a fever; he immediately takes her by the hand, heals her, and raises her. After sunset, since the Sabbath is over the people can go out and bring the sick to Him; He heals a multitude of people afflicted with maladies of every kind: physical, psychological, and spiritual. Having come to earth to proclaim and to realize the salvation of the whole man and of all people, Jesus shows a particular predilection for those who are wounded in body and in spirit: the poor, the sinners, the possessed, the sick, the marginalized. Thus, He reveals Himself as a doctor both of souls and of bodies, the Good Samaritan of man. He is the true Saviour: Jesus saves, Jesus cures, Jesus heals.

The reality of Christ’s healing of the sick invites us to reflect on the meaning and virtue of illness. This also reminds us of the World Day of the Sick, which we shall celebrate on Wednesday, 11 February, the liturgical memorial of Our Lady of Lourdes. I bless the initiatives prepared for this Day, in particular the Vigil that will take place in Rome on the evening of 10 February. Let us also remember the President of the Pontifical Council for Health Care Workers (Health Pastoral Care), Archbishop Zygmunt Zimowski, who is very sick in Poland. A prayer for him, for his health, because it was he who organized this Day, and he accompanies us in his suffering on this Day. Let us pray for Archbishop Zimowski.

The salvific work of Christ is not exhausted with his Person and in the span of his earthly life; it continues through the Church, the sacrament of God’s love and tenderness for mankind. In sending his disciples on mission, Jesus confers a double mandate on them: to proclaim the Gospel of salvation and to heal the sick (cf. Mt 10:7-8). Faithful to this teaching, the Church has always considered caring for the sick an integral part of her mission.

“The poor and the suffering you will always have with you”, Jesus admonishes (cf. Mt 26:11), and the Church continually finds them along her path, considering those who are sick as a privileged way to encounter Christ, to welcome and serve him. To treat the sick, to welcome them, to serve them, is to serve Christ: the sick are the flesh of Christ.

This also occurs in our own time, when, notwithstanding the many scientific break-throughs, the interior and physical suffering of people raises serious questions about the meaning of illness and pain, and about the reason for death. They are existential questions, to which the pastoral action of the Church must respond with the light of faith, having before her eyes the Crucifixion, in which appears the whole of the salvific mystery of God the Father, who out of love for human beings did not spare his own Son (cf. Rm 8:32). Therefore, each one of us is called to bear the light of the Word of God and the power of grace to those who suffer, and to those who assist them — family, doctors, nurses — so that the service to the sick might always be better accomplished with more humanity, with generous dedication, with evangelical love, with tenderness. Mother Church, through our hands, caresses our suffering and treats our wounds, and does so with the tenderness of a mother.

Let us pray to Mary, Health of the Sick, that every person who is sick might experience, thanks to the care of those who are close to them, the power of God’s love and the comfort of her maternal tenderness.

[Pope Francis, Angelus 8 February 2015]

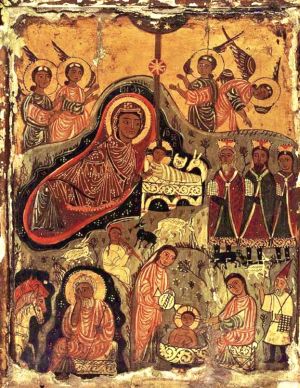

Epiphany of the Lord

Epiphany of the Lord (year A) [6 January 2026]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us! Happy Epiphany!

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (60:1-6)

In these dark days, here is an announcement of light! This text from Isaiah is filled with insistent images of light: "Arise, shine, for your light has come, and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you... The Lord shines upon you... His glory appears upon you... Then you will see and be radiant." It is precisely this abundance of light that makes us understand that the real climate is anything but bright. The prophets do not cultivate paradox, but the art of hope: they speak of light because the people are immersed in the darkest night. The historical context is that of the post-exile period (525-520 BC). The return from Babylon did not bring the expected prosperity. Tensions are high: between those who remained in the country and those returning from exile; between different generations; between Jews and foreign populations settled in Jerusalem during the occupation. The most painful issue concerns the reconstruction of the Temple: the returnees refuse the help of groups considered religiously unfaithful; this gives rise to a conflict that blocks the work and dampens enthusiasm. As the years passed, discouragement set in. It was here that Isaiah, together with the prophet Haggai (cf. 1:2-8, 12-15; 2:3-9), provoked a spiritual awakening. Sadness is not worthy of the people of the promises. The prophet's one great argument is this: Jerusalem is the city chosen by God, the place where He has placed His Name. For this reason, Isaiah can dare to say: 'Arise, Jerusalem! Shine forth'. Even when everything seems dark, God's faithfulness remains the foundation of hope. The almost triumphal language does not describe a situation that has already been resolved, but anticipates the day that is coming. In the night, we look for the dawn: the prophet's task is to restore courage, to remember the promise. The message is clear: do not be discouraged; get to work, rebuild the Temple, because the light of the Lord will come. Three final points: Faith combines lucidity and hope: seeing reality does not extinguish trust. The promise is not a political triumph, but God's victory, his glory that illuminates humanity. Jerusalem already points to the people and, beyond the people, to all humanity called to communion: God's plan transcends every city and every border.

*Important elements: +Post-exilic context (525-520 BC) and climate of discouragement. +Internal conflicts and blockage of the reconstruction of the Temple. +Language of light as an announcement of hope in the night. +Vocation of Jerusalem: chosen city, place of Presence. +Prophetic call to action: rise up and rebuild. +Hope based on God's faithfulness, not on political successes. +Universal openness: the promise concerns all humanity

*Responsorial Psalm (71/72)

Men dream and God carries out his plan. Psalm 71 ideally brings us into the celebration of a king's coronation. The accompanying prayers express the deepest desires of the people: justice, peace, prosperity for all, to the ends of the earth. It is the great dream of humanity throughout the ages. Israel, however, has a unique certainty: this dream coincides with God's own plan. The last verse of the psalm, which blesses only the Lord and not the king, offers us the key to understanding. The psalm was composed after the exile, at a time when there was no longer a king in Israel. This means that the prayer is not addressed to an earthly sovereign, but to the king promised by God, the Messiah. And since it is a divine promise, it is certain. The whole Bible is permeated with this unshakeable hope: history has meaning and direction. The prophets call it 'the Day of the Lord', Matthew 'the Kingdom of Heaven', Paul 'the merciful plan'. It is always the same plan of love that God tirelessly proposes to humanity. The Messiah will be its fulfilment, and it is He whom Israel invokes in praying the psalms. This Psalm describes the ideal king, awaited for centuries, in continuity with the promise made to David through the prophet Nathan: a kingdom stable forever, a king called the son of God. Over the centuries, this promise has been deepened: if the king is the son of God, then his kingdom will be founded on justice and peace. Each new coronation rekindled this expectation. Yet the ideal kingdom has not yet been fully realised. It may seem like a utopia. But for the believer it is not: it is a promise from God, and therefore a certainty. Faith is the anchor of the soul: in the face of the failures of history, the believer does not give up hope, but waits patiently, certain of God's faithfulness. The psalm announces a decisive reversal: power and justice will finally coincide. In God, power is only love. For this reason, the messianic king will free the poor, defend the weak and bring endless peace. His kingdom will have no boundaries: it will extend to the whole earth and last forever. For Israel, this psalm remains a prayer of expectation for the Messiah. For Christians, it is fulfilled in Jesus Christ, and the episode of the Wise Men is already a sign of the universality of his kingdom: the nations come to him, bringing gifts and adoration.

*Important elements: +Psalm 71 as a prayer for the universal desires for justice and peace. +Coincidence between man's dream and God's plan. +Post-exilic composition: waiting for the king-Messiah. +Promise made to David (2 Sam 7) as the foundation of expectation. +History has meaning and direction in God's plan. +The ideal king: justice, peace, defence of the poor. +God's power as love and service. +Universal and endless kingdom. +Messianic Jewish reading and Christian fulfilment in Jesus Christ. + The Wise Men as the first sign of the fulfilment of the universal promise

*Second Reading from St Paul's Letter to the Ephesians (3:2...6)

This passage is taken from the Letter to the Ephesians (chapter 3) and takes up a central theme already announced in chapter 1: the 'merciful plan/mystery of God'. Paul recalls that God has made known the mystery of his will: to bring history to its fulfilment, recapitulating in Christ all that is in heaven and on earth (Eph 1:9-10). For St Paul, the mystery is not a closely guarded secret, but God's intimacy offered to man. It is a plan that God reveals progressively, with patient pedagogy, just as a parent accompanies a child in the discovery of life. Thus God has guided his people throughout history, step by step, until the decisive revelation in Jesus Christ. With Christ, a new era begins: before and after him. The heart of the mystery is this: Christ is the centre of the world and of history. The whole universe is called to be reunited in Him, like a body around its head. Paul emphasises that this unity concerns all nations: all are associated in sharing the same inheritance, in forming the same body, in participating in the same promise through the Gospel. In other words: the inheritance is Christ, the promise is Christ, the body is Christ. When we say "Thy will be done" in the Lord's Prayer, we are asking for the fulfilment of this plan. God's plan is therefore universal: it concerns not only Israel, but all humanity. This openness was already present in the promise made to Abraham: "All the families of the earth shall be blessed in you" (Gen 12:3), and proclaimed by prophets such as Isaiah. However, this truth was slowly understood and often forgotten. At the time of Paul, it was not at all obvious to accept that pagans were fully participants in salvation. The early Christians of Jewish origin struggled to recognise them as full members. Paul intervenes decisively: pagans too are called to be witnesses and apostles of the Gospel. It is the same message that Matthew expresses in the story of the Wise Men: the nations come to the light of Christ. The text ends with an appeal: God's plan requires the cooperation of man. If there was a star for the Wise Men, for many today the star will be the witnesses of the Gospel. God continues to fulfil his benevolent plan through the proclamation and life of believers.

*Important elements: +The 'mystery' as a revelation of God's benevolent plan and progressive revelation culminating in Christ. +Christ as the centre of history and the universe and all humanity united in Christ: heritage, body and promise. Universality of salvation: Jews and pagans together in continuity with the promise to Abraham and the prophets. +Historical difficulties in accepting pagans. +Epiphany and Wise Men as a sign of universalism and Call to witness: collaborating in the proclamation of the Gospel

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (2:1-12)

At the time of Jesus, the expectation of the Messiah was very intense. People spoke of him everywhere and prayed to God to hasten his coming. Most Jews imagined the Messiah as a king descended from David: he would reign from Jerusalem, drive out the Romans and finally establish peace, justice and brotherhood in Israel; some even hoped that this renewal would extend to the whole world. This expectation was based on various prophecies in the Old Testament. First of all, that of Balaam in the Book of Numbers: called to curse Israel, he instead announced a promise of glory, speaking of a star rising from Jacob and a sceptre rising from Israel (Num 24:17). Over the centuries, this prophecy was interpreted in a messianic sense, to the point of suggesting that the coming of the Messiah would be marked by a star. This is why Herod takes the news brought by the Wise Men very seriously. Another decisive prophecy is that of Micah, who announces the birth of the Messiah in Bethlehem, the small village from which the ruler of Israel will come (Micah 5:1), in continuity with the promise made to David of a dynasty destined to last. The Wise Men, probably pagan astrologers, do not have a deep knowledge of the Scriptures: they set out simply because they have seen a new star. When they arrive in Jerusalem, they inquire with the authorities. Here a first great contrast emerges: on the one hand, the Wise Men, who seek without prejudice and ultimately find the Messiah; on the other, those who know the Scriptures perfectly but do not move, do not even make the short journey from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, and therefore do not encounter the Child. Herod's reaction is yet different. Jealous of his power and known for his violence, he sees the Messiah as a dangerous rival. Behind an apparent calm, he seeks precise information: the place of birth and the age of the child. His anguish and fear lead him to the cruel decision to kill all children under the age of two. In the story of the Wise Men, Matthew already offers us a summary of the entire life of Jesus: from the beginning, He encounters hostility and rejection from political and religious authorities. He will not be recognised as the Messiah, He will be accused and finally eliminated. Yet He is truly the promised Messiah: anyone who seeks Him with a sincere heart, like the Wise Men, can enter into God's salvation.

*St John Chrysostom on the episode of the Wise Men: "The Wise Men, though foreigners, rose, departed and came to the Child; so too must those who wish to encounter Christ move with a fervent heart, without waiting for comfort or security." (Homily VII on Matthew 2)

*Most important elements: +Strong messianic expectation at the time of Jesus and expectation of a Messiah-king, descendant of David. +Prophecy of the star (Balaam) and birth in Bethlehem (Micah). +The Wise Men: sincere seekers guided by the star. +Contrast between those who seek and those who know but do not move. +Herod's hostility, jealousy of power and violence. +Jesus rejected from the beginning of his life. + Universality of salvation: those who seek, find. + The Wise Men as a model of faith on the journey.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole

And quite often we too, beaten by the trials of life, have cried out to the Lord: “Why do you remain silent and do nothing for me?”. Especially when it seems we are sinking, because love or the project in which we had laid great hopes disappears (Pope Francis)

E tante volte anche noi, assaliti dalle prove della vita, abbiamo gridato al Signore: “Perché resti in silenzio e non fai nulla per me?”. Soprattutto quando ci sembra di affondare, perché l’amore o il progetto nel quale avevamo riposto grandi speranze svanisce (Papa Francesco)

The Kingdom of God grows here on earth, in the history of humanity, by virtue of an initial sowing, that is, of a foundation, which comes from God, and of a mysterious work of God himself, which continues to cultivate the Church down the centuries. The scythe of sacrifice is also present in God's action with regard to the Kingdom: the development of the Kingdom cannot be achieved without suffering (John Paul II)

Il Regno di Dio cresce qui sulla terra, nella storia dell’umanità, in virtù di una semina iniziale, cioè di una fondazione, che viene da Dio, e di un misterioso operare di Dio stesso, che continua a coltivare la Chiesa lungo i secoli. Nell’azione di Dio in ordine al Regno è presente anche la falce del sacrificio: lo sviluppo del Regno non si realizza senza sofferenza (Giovanni Paolo II)

For those who first heard Jesus, as for us, the symbol of light evokes the desire for truth and the thirst for the fullness of knowledge which are imprinted deep within every human being. When the light fades or vanishes altogether, we no longer see things as they really are. In the heart of the night we can feel frightened and insecure, and we impatiently await the coming of the light of dawn. Dear young people, it is up to you to be the watchmen of the morning (cf. Is 21:11-12) who announce the coming of the sun who is the Risen Christ! (John Paul II)

Per quanti da principio ascoltarono Gesù, come anche per noi, il simbolo della luce evoca il desiderio di verità e la sete di giungere alla pienezza della conoscenza, impressi nell'intimo di ogni essere umano. Quando la luce va scemando o scompare del tutto, non si riesce più a distinguere la realtà circostante. Nel cuore della notte ci si può sentire intimoriti ed insicuri, e si attende allora con impazienza l'arrivo della luce dell'aurora. Cari giovani, tocca a voi essere le sentinelle del mattino (cfr Is 21, 11-12) che annunciano l'avvento del sole che è Cristo risorto! (Giovanni Paolo II)

Christ compares himself to the sower and explains that the seed is the word (cf. Mk 4: 14); those who hear it, accept it and bear fruit (cf. Mk 4: 20) take part in the Kingdom of God, that is, they live under his lordship. They remain in the world, but are no longer of the world. They bear within them a seed of eternity a principle of transformation [Pope Benedict]

Cristo si paragona al seminatore e spiega che il seme è la Parola (cfr Mc 4,14): coloro che l’ascoltano, l’accolgono e portano frutto (cfr Mc 4,20) fanno parte del Regno di Dio, cioè vivono sotto la sua signoria; rimangono nel mondo, ma non sono più del mondo; portano in sé un germe di eternità, un principio di trasformazione [Papa Benedetto]

In one of his most celebrated sermons, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux “recreates”, as it were, the scene where God and humanity wait for Mary to say “yes”. Turning to her he begs: “[…] Arise, run, open up! Arise with faith, run with your devotion, open up with your consent!” [Pope Benedict]

duevie.art

don Giuseppe Nespeca

Tel. 333-1329741

Disclaimer

Questo blog non rappresenta una testata giornalistica in quanto viene aggiornato senza alcuna periodicità. Non può pertanto considerarsi un prodotto editoriale ai sensi della legge N°62 del 07/03/2001.

Le immagini sono tratte da internet, ma se il loro uso violasse diritti d'autore, lo si comunichi all'autore del blog che provvederà alla loro pronta rimozione.

L'autore dichiara di non essere responsabile dei commenti lasciati nei post. Eventuali commenti dei lettori, lesivi dell'immagine o dell'onorabilità di persone terze, il cui contenuto fosse ritenuto non idoneo alla pubblicazione verranno insindacabilmente rimossi.