(Mk 10:17-30)

Mark 10:17 As he was leaving to set out on his journey, a man ran up to him and, throwing himself down on his knees before him, asked him, "Good Teacher, what must I do to have eternal life?"

Mark 10:18 Jesus said to him, "Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone.

Mark 10:19 You know the commandments: Thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not commit adultery, thou shalt not steal, thou shalt not bear false witness, thou shalt not defraud, and honour thy father and thy mother."

Mark 10:20 He then said to him, "Teacher, all these things I have kept from my youth."

Mark 10:21 Then Jesus stared at him, and loved him, and said to him, "One thing you lack: go, sell what you have and give it to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come and follow me."

Mark 10:22 But he was grieved at these words, and went away afflicted, for he had many possessions.

"As he went out to set out on his journey." Mark reminds his readers that this is the journey that leads to Jerusalem. And it is precisely on this journey that we have the framework and the key to the story.

The evangelist wants to emphasise the importance of trusting in Jesus and trusting in him and not in one's own wealth and, therefore, in oneself. He describes the encounter of this character in search of the perfect way very well: he runs towards Jesus and kneels before him, thus expressing his desire to meet the Master (he runs towards him) and his trust in him (he throws himself on his knees before Jesus). Bear in mind that everything here takes place on the road to Jerusalem and from there to Golgotha. This is the perfect way, the road that leads to eternal life, incomprehensible to those who put their trust in themselves and their possessions: doing the will of the Father. Hence the need to strip oneself of oneself and follow Jesus, for he is the Way that leads to the Father, to eternal life, and on this Way is stamped the mark of the cross.

The question around which the whole story revolves is a question: "Good Teacher, what must I do to have eternal life?". Jesus is referred to as a 'good Master', where the term 'Master' defines the relationship between Jesus and this fellow, who stands in an attitude of disciple and, therefore, well disposed to accept the teaching of Jesus, who here, in a certainly anomalous way in defining a master, is called 'good'. A master can be called wise, enlightened, learned, knowledgeable, all attributes that highlight his position as a master and define his quality. It does not make much sense for Jesus to be called 'good' and Jesus immediately notes this as inappropriate for him, since, as a good Jew, Jesus knows that this attribute is only to be referred to and publicly acknowledged by God. Jesus, therefore, refers the search for this rich man back to God himself. The key that opens to "eternal life" belongs to the Father, but Jesus can point the way to the commandments, in which the very will of God is reflected and are placed as the seal of the Covenant, which underlies the very identity of the people of Israel.

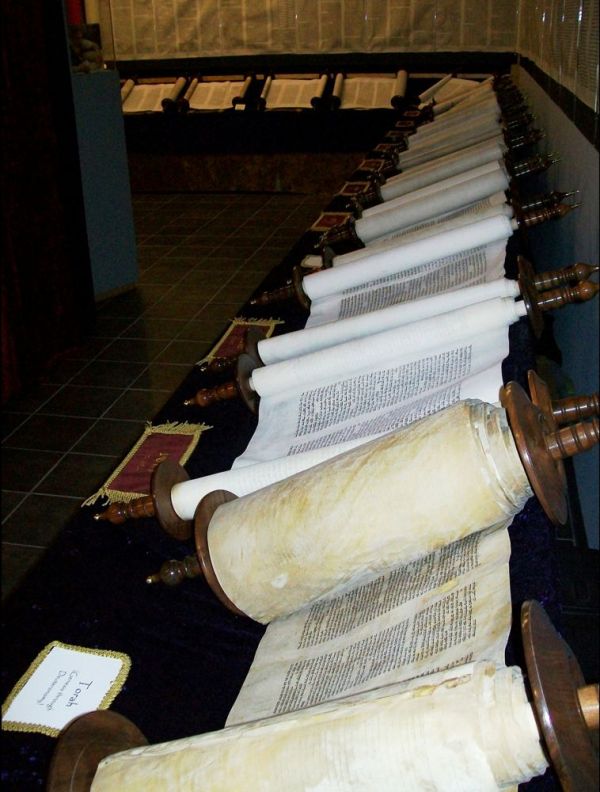

The question posed by the rich man is "what must I do to have eternal life?". The question is part of the rabbinic debate, which is constantly searching for a sophisticated way of perfection or some commandment that can somehow sum up the very large number of all the other commandments of the Torah, as many as 613, which marked and still mark the life of the pious Jew. The Jewish religion is conceived as a kind of religious practice, a mere execution of divine orders and commands. The Torah, in fact, was understood as an expression of the divine will, which as such was only to be performed and not discussed. Upon proper execution, God was bound to give his faithful the promised reward. It was, therefore, a sort of contractual relationship, which the pious Jew had entered into with God within the framework of the Covenant. Within this logic we understand the rich man's request "what must I do to get". We are, therefore, still in the sphere of a contractualist logic, that of doing in order to have, but at the same time it hints at the profound desire to be open to a new relationship with God, capable of overcoming the old schemes. And it is precisely this need for inner renewal and spiritual growth that directed this one to Jesus.

With v. 19, Jesus points out the way, open to every pious Jew and to all men of good will, since the commandments are nothing but a law that is inscribed in man's very nature and shows him the path to follow. The commandments that Jesus lists concern only the relationship with others, omitting, instead, the first part of the Decalogue concerning the relationship with God. This choice of field made by Jesus, however, does not exclude relations with God, but completes them and constitutes the "conditio sine qua non". One cannot, in fact, love God whom one cannot see if one does not love one's neighbour whom one can see. Love for God passes through love for one's neighbour.

In the list of commandments, Mark adds a "Mē aposterēsēs" (do not defraud), which in fact does not exist among the commandments, but which in fact summarises Ex 20:17: "You shall not covet your neighbour's house. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife, nor his slave, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor anything belonging to thy neighbour'. The verb "aposterēō" (to defraud), which Mark uses here instead of "not to covet", means not only to defraud, but also "to deprive, to strip, to take away, to defraud, not to give what is due". The meaning that Mark here wants to attribute to that original 'not to covet' is that of an underhand and deceitful taking away of a good that belongs to one's neighbour. The reason for this choice on Mark's part, i.e. to replace "not to covet" with "not to defraud", must be understood for the audience of readers to whom Mark addresses his gospel: the community of Rome, for whom "to covet" is a simple motion of the soul, while for the Jewish mentality and culture "to covet" takes on much more concrete aspects, that is, to engage in behaviour such as to be able to subtract from another, in a devious and deceitful manner, the "desired" good. A concept that for the Romans was better expressed as "defrauding".

V. 20 reports the response of the rich man, who testifies that he has observed such things since his youth. The reference here is probably to the "bar mitzvah" (son of the commandment), a ceremony that is celebrated at the age of 13 for the male. This is the moment when the young man, now on the threshold of adolescence, makes his official entry into the civil and religious community, assuming his first responsibilities, taking an active part in religious and social life. He can from this moment be counted in the 'Minian', the minimum number of ten people for public prayer in the synagogue to be communal.

Jesus' response is articulated in three moments that constitute a sort of gradual path towards spiritual perfection: a) the observation that the mere observance of the Torah, however perfect, does not adequately satisfy this person's need for spirituality: "One thing you lack". This is a clear sign that the Mosaic Law was not able to give that spiritual perfection capable of creating an adequate communion between the believer and God. b) The second moment creates the condition for accessing this perfection: freeing oneself from all material bonds, which bind the possessor to the earthly, preventing him from any spiritual elevation: "sell all you have and give it to the poor and you will have treasure in heaven". This is not a simple repudiation of earthly goods, but a "distribution" of them to those in need and, therefore, a sort of sharing, which becomes a communion of life, thus transforming this material and perishable wealth into a spiritual and eternal one. c) The third element, which constitutes Jesus' response, is following: "then come and follow me". The verb used here is "akolouthei", and expresses a following that places itself at the service of Jesus. This is a technical verb used by the evangelists to define the relationship between the disciple who has decided his life for Jesus and Jesus himself.

The discipleship, therefore, is a gradual path, which stems from the need for spiritual perfection, to give a deeper and truer meaning to one's life; hence the need to free oneself from the material constraints that can condition the path of spiritual growth; and finally the following of Jesus, as the culminating moment of this path of spirituality, which begins precisely with the spoliation of oneself.

V. 22 closes the story about the rich man seeking the path to perfection with a note of sadness that leaves a very bitter taste in the mouth: "when he was saddened by these words, he went away sorrowful", because, the evangelist comments, "he had many possessions". A sadness, therefore, that is linked to possessions, because it is precisely these that prevent him from accessing that perfection to which he so aspired. A sadness that indicates the frustration of a great desire for God. For discipleship to be effective, it requires one's heart to be completely free from the materiality of living, for it is not a path of power and personal affirmation, but of spirituality, which by transcending materiality evolves the disciple towards God and leads him to him through service to others.

Argentino Quintavalle, author of the books

- Revelation - exegetical commentary

- The Apostle Paul and the Judaizers - Law or Gospel?Jesus Christ true God and true Man in the Trinitarian mystery

The prophetic discourse of Jesus (Matthew 24-25)

All generations will call me blessed

Catholics and Protestants compared - In defence of the faith

(Buyable on Amazon)