Christmas Day 2025 [Midnight Mass]

May God bless you and may the Virgin Mary protect us. Best wishes for this holy Christmas Day of Christ. I offer for your consideration a commentary on the biblical texts of the midnight and daytime Masses.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (9:1-6)

To understand Isaiah's message in this text, one must read this verse, the last of chapter 8, which directly precedes it: 'God humbled the land of Zebulun and Naphtali in the past, but in the future he will glorify the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the nations' (v. 23). The text does not allow us to establish the date of its writing with precision, but we know two things with certainty: the political situation to which it refers, even if the text may have been written later. And we also know the meaning of the prophetic word, which seeks to revive the hope of the people. At the time evoked, the people were divided into two kingdoms: in the north, Israel, with its capital at Samaria, politically unstable; in the south, the kingdom of Judah, with its capital at Jerusalem, the legitimate heir to the Davidic dynasty. Isaiah preached in the South, but the places mentioned (Zebulun, Naphtali, Galilee, the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan) belong to the North. These areas – Galilee, the way of the sea, Transjordan – suffered a particular fate between 732 and 721 BC. In 732, the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III annexed these regions. In 721, the entire northern kingdom fell. Hence the image of 'the people walking in darkness', perhaps referring to the columns of deportees. To this defeated people, Isaiah announces a radical reversal: God will bring forth a light in the very regions that have been humiliated. Why do these promises also concern the South? Jerusalem is not indifferent to what is happening in the North: because the Assyrian threat also hangs over it; because the schism is experienced as a wound and there is hope for the reunification of the people under the house of David. The advent of a new king, the words of Isaiah ("A great light has risen...") belonged to the ritual of the sacred royal: every new king was compared to a dawn that brings hope for peace and unity. Isaiah therefore announces: the birth of a king ("A child is born for us..."), called "Prince of Peace", destined to restore strength to the Davidic dynasty and reunite the people. This certainty comes from faith in the faithful God, who cannot betray his promises. The prophecy invites us not to forget God's works: Moses reminded us, 'Be careful not to forget'. Isaiah said to Ahaz, 'Unless you believe, you will not be established' (Isaiah 7:9). The promised victory will be "like the day of Midian" (Judges 7): God's victory achieved through a small faithful remnant with Gideon. The central message is "Do not be afraid: God will not abandon the house of David." Today we could say: Do not be afraid, little flock, God does not abandon his plan of love for humanity, and light is believed in the night. Historical context: When Isaiah announces these promises, King Ahaz has just sacrificed his son to idols out of fear of war, undermining the very lineage of David. But God, faithful to his promises, announces a new heir who will restore the line of David: hope is not cancelled out by human sin.

Most important elements. +The context: Assyrian annexations (732–721 BC) devastating the northern regions. +Isaiah's words are a prophecy of hope for a people in darkness.

+The announcement is linked to the sacred royal line: the birth of a new Davidic king. +The promise concerns unity, peace and God's faithfulness to his covenant with David. +Victory will be God's work, like Gideon's victory. +Even Ahaz's sin does not nullify God's plan: God remains faithful.

*Responsorial Psalm (95/96)

The liturgy offers only a few verses from Psalm 95/96, but the entire psalm is filled with a thrill of joy and exultation. Yet it was composed in a historical period that was not at all exciting: what vibrates is not human enthusiasm, but the faith that hopes, that hope that anticipates what is not yet possessed. The psalm projects us to the end of time, to the blessed day when all peoples will recognise the Lord as the one God and place their trust in him. The image is grandiose: we are in the Temple of Jerusalem. The esplanade is filled with an endless multitude of people, gathered 'from the ends of the earth'. Everyone sings in unison: 'The Lord reigns!' It is no longer Israel's acclamation for an earthly king, but the cry of all humanity recognising the King of the world. And it is not only humanity that acclaims: the earth trembles, the seas roar, the countryside and even the trees of the forests dance. The whole of creation recognises its Creator, while man has often taken centuries to do so. The psalm also contains a criticism of idolatry: 'the gods of the nations are nothing'. Over the centuries, the prophets have fought the temptation to rely on false gods and false securities. The psalm reminds us that only the Lord is the true God, the One who 'made the heavens'. The reason why all peoples now flock to Jerusalem is that the good news has finally reached the whole world. And this was possible because Israel proclaimed it every day, recounting the works of God: the liberation from Egypt, the daily liberations from many forms of slavery, the most serious danger: believing in false values that do not save. Israel has received the immense privilege of knowing the one God, as the Shema proclaims: "The Lord is one."

But it has received this privilege in order to proclaim it: "You have been given to see, so that you may know... and make it known." Thanks to this proclamation, the good news has reached "the ends of the earth" and all peoples gather in the "house of the Father." . The psalm anticipates this final scene and, while waiting for it to come true, Israel sings it to renew its faith, revive its hope and find the strength to continue the mission entrusted to it.

Most important elements: +Psalm 95/96 is a song of eschatological hope: it anticipates the day when all humanity will recognise God. +The story describes a cosmic liturgy: humanity and creation together acclaim the Lord. +Strong denunciation of idolatry: the 'gods of the nations' are nothing. +Israel has the task of proclaiming God's works and his deliverance every day. +Its vocation: to know the one God and make him known. +The psalm is sung as an anticipation of the future, to keep the faith and mission of the people alive.

*Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul to Titus (2:11-14) and for the Dawn Mass (3:4-7)

Through Baptism, we are immersed in God's grace. The Cretans had a bad reputation even before St Paul's time. A poet of the 6th century BC, Epimenides of Knossos, called them "liars by nature, evil beasts, lazy bellies". Paul quotes this phrase and adds: "This is true!". And it was precisely because he was well aware of this difficult humanity that Paul founded a Christian community, which he then entrusted to Titus to organise and lead. The Letter to Titus contains the founder's instructions to the leaders of the young Church of Crete. Many scholars believe that the letter was written towards the end of the first century, after Paul's death, but it respects his style and is faithful to his theology. In any case, the difficulties of the Cretans must still have been very much alive. The letter — very short, just three pages — contains concrete recommendations for all categories of the community: elders, young people, men, women, masters, slaves, and even those in charge, who are admonished to be blameless, hospitable, just, self-controlled, and far from violence, greed, and drunkenness. It is a long list of advice that gives an idea of how much work still needed to be done. The central theological passage of the letter—the one proclaimed in the liturgy—explains the foundation of all Christian morality, namely that new life is born from Baptism. Paul links moral advice to a decisive statement: "The grace of God has been revealed for the salvation of all." The message is this: Behave well, because God's grace has been revealed, and this means that moral change is not a human effort, but a consequence of the Incarnation. When Paul says 'grace has been revealed', he means that God became man and, through Baptism, immersed in Christ, we are reborn: saved through the washing of regeneration and renewal in the Holy Spirit (Titus 3:5). We are not saved by our own merits, but by mercy, and God asks us to be witnesses to this. God's plan is the transformation of the whole of humanity, gathered around Christ as one new man. This goal seems distant, and unbelievers consider it a utopia, but believers know and confess that it is promised by God, and therefore it is a certainty. For this reason, we live "in the hope of the blessed hope and the manifestation of the glory of our great God and Saviour Jesus Christ." The words that the priest pronounces after the Our Father in the Mass echo this very expectation: 'while we await the fulfilment of the blessed hope...'. This is not an escape from reality, but an act of faith: Christ will have the last word on history. This certainty nourishes the entire liturgy, and the Church already lives as a humanity already gathered in Christ and reaching towards the future, so that when the end comes, it will be possible to say: "They rose up as one man, and that man was Jesus Christ."

Historical note: When was the Christian community of Crete born? Two hypotheses: During Paul's transfer to Rome (Acts 27), the ship stopped at "Good Harbours" in the south of the island. But the Acts do not mention the founding of a community, and Titus was not present. During a fourth missionary journey after Paul's release: his first imprisonment in Rome was probably "house arrest"; once freed, Paul would have evangelised Crete on this last journey.

Important points to remember: +The Cretans were considered difficult, but Paul founded a community there anyway. +The Letter to Titus contains concrete instructions for structuring the nascent Church. +Christian morality arises from the Incarnation and Baptism, not from mere human effort. +God saves through mercy and asks for witness, not merit. +God's plan: to reunite humanity in Christ as one new man. +The expectation of the 'blessed hope' is certainty and sustains liturgical life.

*From the Gospel according to Luke (2:1-14)

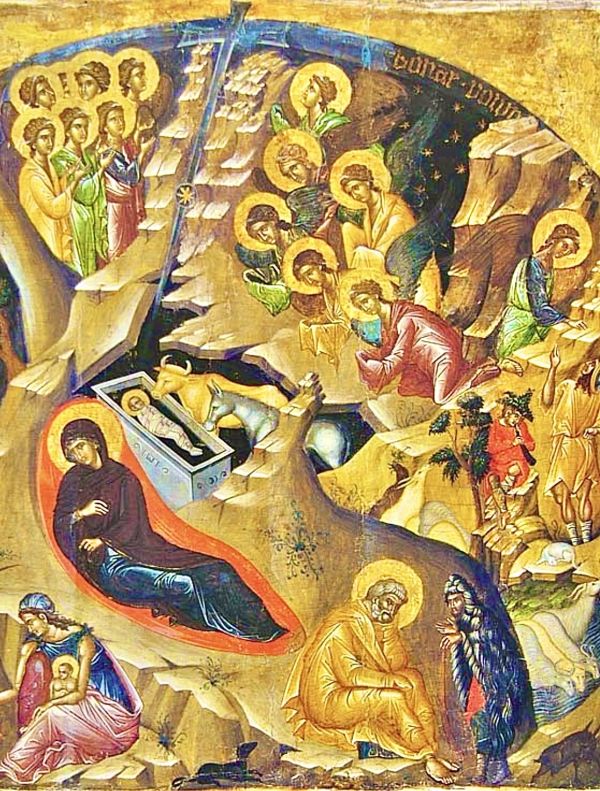

Isaiah, announcing new times to King Ahaz, speaks of the 'jealous love of the Lord' as the force capable of fulfilling the promise (Is 9:6). This conviction runs through the entire account of Jesus' birth in Luke's Gospel. The night in Bethlehem resounds with the angels' announcement: "Peace to those whom the Lord loves," which would be better said as "Peace to those whom God loves." In fact, there are no "loved and unloved people" because God loves everyone and gives his peace to all. God's entire plan is encapsulated in this phrase, which John summarises as follows: "God so loved the world that he gave his only Son" (Jn 3:16). Faced with a God who presents himself as a newborn baby, there is nothing to fear: perhaps God chose to be born in this way so that our fears of him would fall away forever. Like Isaiah in his time, the angel also announces the birth of the expected King: "Today a Saviour, Christ the Lord, is born to you in the city of David. He is the son promised in Nathan's prophecy to David (2 Sam 7): a stable lineage, a kingdom that lasts forever. This is why Luke insists on Joseph's origins: he belongs to the house of David and, for the census, he goes up to Bethlehem, a place also indicated by the prophet Micah as the homeland of the Messiah, who will be the shepherd of the people and the bringer of peace (Mic 5). The angels therefore announce "great joy" . But what is surprising is the contrast between the greatness of the Messiah's mission and the smallness , the minority of his conditions: the 'heir of all things' (Heb 1:2) is born among the poor, in the dim light of a stable; the Light of the world appears almost voluntarily hiding himself; the Word that created the world wants to learn to speak like any newborn baby. And in this light, it is not surprising that many "did not recognise him". The sign of God is not in the exceptional but in the simple and poor everyday life: it is there that the mystery of the Incarnation is revealed, and the first to recognise it are the little ones and the poor, because God, the "Merciful One", allows himself to be attracted only by our poverty. Bending down over the manger in Bethlehem, then, means learning to be like Him, because it is from this humble 'cathedra' that the almighty God communicates to us the power to become children of God (Jn 1:12).

*Final note. The firstborn, a legal term, had to be consecrated to God, and in biblical language this does not mean that other children came after Jesus, but that there were none before him. Bethlehem literally means 'house of bread'; the Bread of Life is given to the world. The titles attributed to Jesus recall those attributed to the Roman emperor venerated as 'god' and 'saviour', but the only one who can truly bear these titles is the newborn child of Bethlehem.

Key points to remember: +Isaiah and the 'jealous love of the Lord': the promise of a future king (Isaiah 9:6). +Announcement of the angels: 'Peace to men because God loves them'. +The heart of the Gospel: 'God so loved the world that he gave his only Son' (John 3:16). +The newborn child eliminates all fear of God: God chooses the way of fragility. +Fulfillment of promises +Nathan's prophecy to David (2 Sam 7). +Micah's prophecy about Bethlehem (Mic 5). +Joseph: Davidic descent. +Surprising contrast: greatness of the Messiah vs. extreme poverty of birth. +Christological titles: "Heir of all things" (Heb 1:2). "Light of the world". "Word" who becomes a child. +The sign of God is poor normality: the mystery of the Incarnation in everyday life +The poor and the little ones recognise him first. +Our vocation: to become children of God (Jn 1:12) by imitating his mercy.

St Ambrose of Milan – Brief commentary on Lk 2:1-14 “Christ is born in Bethlehem, the ‘house of bread’, so that it is understood from the beginning that He is the Bread that came down from heaven. His manger is the sign that He will be our nourishment. The angels announce peace, because where Christ is, there is true peace. And the shepherds are the first to receive the news: this means that grace is not given to the proud, but to the simple. God does not manifest himself in the palaces of the powerful, but in poverty; thus he teaches that those who want to see the glory of God must start from humility."

Christmas Day 2025 [Mass of the Day]

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (52:7-10)

The Lord comforts his people. The cry, "Break forth together into songs of joy, ruins of Jerusalem," places Isaiah's text precisely in the time of the Babylonian Exile (587 BC), when Jerusalem was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar's army. The devastated city, the deportation of the people, and the long wait for their return had led to discouragement and loss of hope. In this context, the prophet announces a decisive turning point: God has already acted. The words "Comfort, comfort my people" become a certainty that the return is imminent. Isaiah imagines two symbolic figures: the messenger, who runs to announce the good news, and the watchman, who sees the liberated people advancing from the walls of Jerusalem. In the ancient world, the messenger on foot was the only means of rapid communication, while the watchman kept vigil from the top of the walls or hills. Thus Isaiah sings of the beauty of the footsteps of those who announce peace, salvation and good news. Not only is the people saved, but the city will also be rebuilt: for this reason, even the ruins are invited to rejoice. The liberation of Israel manifests the power of God, who shows 'his holy arm'. As in the Exodus from Egypt, God intervenes forcefully to redeem his people. Isaiah uses the term 'He has redeemed Jerusalem' (Go'el): God is the closest relative who liberates, not out of self-interest, but out of love. During the exile, the people come to a fundamental discovery: the election of Israel is not an exclusive privilege, but a universal mission. God's salvation is intended for all nations, so that every people may recognise the Lord as Saviour. Re-read in the light of Christmas, this announcement finds its fulfilment: God has definitively shown his holy arm in Jesus Christ. Today, the mission of believers is that of the messenger: to announce peace, the good news, and to proclaim to the world that God reigns.

Most important elements in the text: +God (the Lord) is the true protagonist: Go'el, liberator, king who returns to Zion. + Israel, the chosen people, freed from exile, is called to a universal mission. +The messenger is the figure who announces the good news, peace and salvation. +The watchman, the one who keeps watch, recognises the signs of salvation and announces the coming of the Lord. +Jerusalem (the holy city) destroyed but destined for reconstruction; symbol of the restored people.

*Responsorial Psalm (97/98)

As always, only a few verses are proclaimed, but the commentary covers the entire psalm, whose theme is: the people of the Covenant... at the service of the Covenant of peoples. All the ends of the earth have seen the victory of our God': it is the people of Israel who speak and say 'our God', thus affirming the unique and privileged bond that unites them to the God of the universe. However, Israel has gradually come to understand that this relationship is not an exclusive possession, but a mission: to proclaim God's love to all people and to bring the whole of humanity into the Covenant. The psalm clearly expresses what can be defined as 'the two loves of God': faithful love for his chosen people, Israel; universal love for all nations, that is, for the whole of humanity. On the one hand, it proclaims that the Lord has made known his victory and his justice to the nations; on the other hand, it recalls his faithfulness and love for the house of Israel, formulas that recall the whole history of the Covenant in the desert, when God revealed himself at Sinai as a God of love and faithfulness (Ex 19-24). The election of Israel, therefore, is not a selfish privilege, but a fraternal responsibility: to be an instrument for all peoples to enter into the Covenant. As André Chouraqui stated, the people of the Covenant are called to become instruments of the Covenant of peoples. This universal openness is also emphasised by the literary structure of the psalm, constructed according to the process of 'inclusion'. The central phrase, which speaks of God's faithfulness to Israel, is framed by two statements that concern all humanity: at the beginning, the nations; at the end, the whole earth. In this way, the text shows that the election of Israel is central, but oriented towards radiating salvation to all. During the Feast of Tabernacles in Jerusalem, Israel acclaims the Lord as king, aware that it is already doing so on behalf of all humanity, anticipating the day when God will be recognised as king of the whole earth. The psalm thus insists on a second fundamental dimension: the kingship of God. The acclamation is not a simple song, but a true cry of victory (teru‘ah), similar to that which was raised on the battlefield or on the day of a king's coronation. The theme of victory returns several times: the Lord has won with his holy arm and his mighty hand, he has manifested his justice to the nations, and the whole earth has seen his victory. This victory has a twofold meaning. On the one hand, it recalls the liberation from Egypt, God's first great act of salvation, remembered in the images of his mighty arm and the wonders performed in the crossing of the sea. On the other hand, it announces the final and eschatological victory, when God will triumph definitively over every force of evil. For this reason, the acclamation is full of confidence: unlike the kings of the earth, who disappoint, God does not disappoint. Christians, in the light of the Incarnation, can proclaim with even greater force that the King of the world has already come and that the Kingdom of God, the Kingdom of love, has already begun, even if it has yet to be fully realised.

Important elements of the text: +The privileged relationship between Israel and God, +Israel's universal mission in the service of humanity. +The "two loves of God": for Israel and for all nations. +The Covenant as God's faithfulness and love in history. +The literary structure of "inclusion". +The proclamation of God's kingship and the cry of victory (teru'ah) and liturgical language. +The memory of the liberation from Egypt and the expectation of God's final victory at the end of time. +The Christian reinterpretation in the light of the Incarnation. +The reference to musical instruments of worship. + The image of God's power, which at Christmas is manifested in the fragility of a child.

*Second Reading from the Letter to the Hebrews (1:1-6)

The statement "God spoke to the fathers through the prophets" shows that the Letter to the Hebrews is addressed to Jews who have become Christians. Israel has always believed that God revealed himself progressively to his people: since God is not accessible to man, it is He who takes the initiative to make himself known. This revelation takes place through a gradual process of teaching, similar to the education of a child, as Deuteronomy reminds us: God educates his people step by step. For this reason, in every age, God has raised up prophets, considered to be the 'mouth of God', who have spoken in a way that was understandable to their time. He has spoken 'many times and in many ways', forming his people in the hope of salvation. With Jesus Christ, however, we enter the time of fulfilment. The author of the Letter to the Hebrews distinguishes two great periods: the time before Christ and the time inaugurated by Christ. In Jesus, God's merciful plan of salvation finds its full fulfilment: the new world has already begun. After the resurrection, the early Christians gradually came to understand that Jesus of Nazareth was the expected Messiah, but in an unexpected form. Expectations were different: a Messiah-king, a Messiah-prophet, a Messiah-priest. The author affirms that Jesus is all of these together.

Jesus is the prophet par excellence: while the prophets were the voice of God, Jesus is the very Word of God, through whom everything was created. He is the reflection of the Father's glory and its perfect expression: whoever sees Him sees the Father. As a priest, Jesus re-establishes the Covenant between God and humanity. Living in perfect filial relationship with the Father, he accomplishes the purification of sins. His priesthood does not consist of external rites, but of a life totally given in love and obedience to the Father. Jesus is also the Messiah-King. The royal prophecies apply to him: he sits at the right hand of the divine Majesty and is called the Son of God, the royal title par excellence. His kingdom surpasses that of the kings of the earth: he is lord of all creation, superior even to the angels, who adore him. This implicitly affirms his divinity. To be Christ, therefore, means to be prophet, priest and king. This text also reveals the vocation of Christians: united with Christ, they share in his dignity. In baptism, believers are made participants in Christ's mission as prophet, priest and king. The fact that this passage is proclaimed at Christmas invites us to recognise all this depth in the child in the manger: He carries within himself the mystery of the Son, the King, the Priest and the Prophet, and we live in Him, with Him and for Him.

Most important elements of the text: +The progressive revelation of God. +The role of prophets in the history of Israel. +Jesus as the definitive fulfilment of revelation. +Christ, the Word of God and reflection of his glory. +Christ, priest who re-establishes the Covenant. +Christ, king, Son of God and Lord of creation. +The unity of the three functions: prophet, priest and king. +The participation of Christians in this mission through baptism

*From the Gospel according to John (1:1-18)

Creation is the fruit of love. 'In the beginning': John deliberately takes up the first word of Genesis ('Bereshit'). It does not indicate a mere chronological succession, but the origin and foundation of all things. "In the beginning was the Word": everything comes from the Word, the Word of love, from the dialogue between the Father and the Son. The Word is "turned towards God" (pros ton Theon), symbolising the attitude of dialogue: looking the other in the eye, opening oneself to encounter. Creation itself is the fruit of this dialogue of love between the Father and the Son, and man is created to live it. We are the fruit of God's love, called to a filial dialogue with Him. Human history, however, shows the rupture of this dialogue: the original sin of Adam and Eve represents distrust in God, which interrupts communion. Conversion, that is, 'turning around', allows us to reconcile dialogue with God. The future of humanity is to enter into dialogue. Christ lives this dialogue with the Father perfectly: He is humanity's 'Yes' to the Father. Through Him, we are reintroduced into the original dialogue, becoming children of God for those who believe in Him. Trust in God ("believing") is the opposite of sin: it means never doubting God's love and looking at the world through His eyes. The Incarnate Word (The Word became flesh) shows that God is present in concrete reality; we do not need to flee from the world to encounter Him. Like John the Baptist, we too are called to bear witness to this presence in our daily lives.

Main elements of the text: +Creation as the fruit of the dialogue of love between the Father and the Son: + In the beginning indicates origin and foundation, not just chronology. +The Word as the creative Word and the beginning of dialogue. +Man created to live in filial dialogue with God

and The breaking of dialogue in original sin. +Conversion as a 'half-turn' to reconcile the relationship with God. +Christ as perfect dialogue and humanity's 'Yes' to the Father. +Becoming children of God through faith. +The presence of God in concrete reality and in the flesh of the Word. +The call of believers to be witnesses of God's presence

Commenting on John's Prologue, St Augustine writes: 'The Word was not created; the Word was with God, and everything was made through Him. He is not merely a message, but the very Wisdom and Love of God who communicates himself to men." Augustine thus emphasises that creation and humanity are not an accident, but the fruit of God's eternal love, and that man is called to respond to this love in dialogue with Him.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole