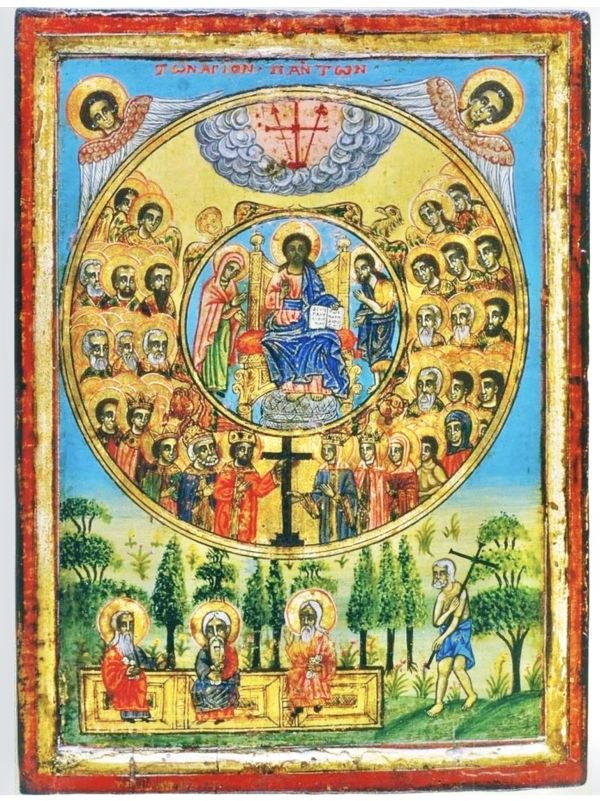

Solemnity of All Saints [1 November 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin Mary protect us. The Solemnity of All Saints is an important occasion to reflect on our Christian vocation: through Baptism, we are all called to be 'blessed', that is, on the path towards the joy of eternal Love.

First Reading from the Book of Revelation of Saint John the Apostle (7:2-4, 9-14)

In Revelation, John recounts a mystical vision he received in Patmos, which is to be interpreted symbolically rather than literally. He sees an angel and an immense crowd, composed of two distinct groups: The 144,000 baptised, marked with the seal of the living God, represent the faithful believers, contemporaries of John, persecuted by the emperor Domitian. They are the servants of God, protected and consecrated, the baptised people who bear witness to their faith despite persecution. The innumerable crowd, from every nation, tribe, people and language, dressed in white, with palm branches in their hands and standing before the Throne and the Lamb, represents humanity saved thanks to the faith and sufferings of the baptised. Their standing position symbolises resurrection, their white robes purification, and their palm branches victory. The central message is that the suffering of the faithful brings about the salvation of others: the trials of the persecuted become a means of redemption for humanity, in continuity with the theme of the suffering servant of Isaiah and Zechariah. John uses symbolic and coded language, typical of the Apocalypse, to secretly communicate with persecuted believers and encourage them to persevere in their faith without being discovered by the Roman authorities. The text therefore invites perseverance: even if evil seems to triumph, the heavenly Father and Christ have already won, and the faithful, though small and oppressed, share in this victory. Baptism is thus perceived as a protective seal, comparable to the mark of Roman soldiers. This text, with its mystical and prophetic language, reveals that the victory of the poor and the little ones is not revenge, but a manifestation of God's triumph over the forces of evil, bringing salvation and hope to all humanity, thanks to the faithful perseverance of the righteous.

Responsorial Psalm (23/24)

This psalm takes us to the Temple of Jerusalem, a holy place built on high. A gigantic procession arrives at the gates of the Temple. Two alternating choirs sing in dialogue: 'Who shall ascend the mountain of the Lord? Who can stand in his holy place?" The biblical references in this psalm are Isaiah (chapter 33), which compares God to a consuming fire, asking who can bear to look upon him. The question is rhetorical: we cannot bear God on our own, but he draws near to man, and the psalm celebrates the discovery of the chosen people: God is holy and transcendent, but also always close to man. Today, this psalm resounds on All Saints' Day with the song of the angels inviting us to join in this symphony of praise to God: 'with all the angels of heaven, we want to sing to you'. The necessary condition for standing before God is well expressed here: only those with a pure heart, innocent hands, who do not offer their souls to idols. It is not a question of moral merit: the people are admitted when they have faith, that is, total trust in the one God, and decisively reject all forms of idolatry. Literally, 'he has not lifted his soul to empty gods', that is, he does not pray to idols, while raising one's eyes corresponds to praying and recognising God. The psalm insists on a pure heart and innocent hands. The heart is pure when it is totally turned towards God, without impurity, that is, without mixing the true and the false, God and idols. Hands are innocent when they have not offered sacrifices or prayed to false gods. The parallelism between heart and hands emphasises that inner purity and concrete physical action must go together. The psalm recalls the struggle of the prophets because Israel had to fight idolatry from the exodus from Egypt (golden calf) to the Exile and beyond, and the psalm reaffirms fidelity to the one God as a condition for standing before Him. "Behold, this is the generation that seeks your face, God of Jacob." Seeking God's face is an expression used for courtiers admitted into the king's presence and indicates that God is the only true King and that faithfulness to Him allows one to receive the blessing promised to the patriarchs. From this flow the concrete consequences of faithfulness: the man with a pure heart knows no hatred; the man with innocent hands does no evil; on the contrary, he obtains justice from God by living in accordance with the divine plan because every life has a mission and every true child of God has a positive impact on society. Also evident in this psalm is the connection to the Beatitudes of the Gospel: "Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness... Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God." "Behold, this is the generation that seeks him, that seeks your face, God of Jacob": is this not a simple definition of poverty of heart, a fundamental condition for entering the Kingdom of Heaven?

Second Reading from the First Letter of Saint John the Apostle (3:1-3)

"Beloved, see what great love the Father has given us": the urgency of opening our eyes. St John invites believers to "see", that is, to contemplate with the eyes of the heart, because the gaze of the heart is the key to faith. Indeed, the whole of human history is an education of the gaze. According to the prophets, the tragedy of man is precisely "having eyes and not seeing". What we need to learn to see is God’s love and “his plan of salvation” (cf. Eph 1:3-10) for humanity. The entire Bible insists on this: to see well is to recognise the face of God, while a distorted gaze leads to falsehood. The example of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden shows how sin arises from a distorted gaze. Humanity, listening to the serpent, loses sight of the tree of life and focuses its gaze on the forbidden tree: this is the beginning of inner disorder. The gaze becomes seduced, deceived, and when "their eyes were opened," humans did not see the promised divinity, but their nakedness, their poverty and fragility. In opposition to this deceived gaze, John invites us to look with our hearts into the truth: 'Beloved, see what great love the Father has given us'. God is not jealous of man — as the serpent had insinuated — but loves him and wants him as his son. John's entire message is summed up in this revelation: 'God is love'. True life consists in never doubting this love; knowing God, as Jesus says in John's Gospel (17:3), is eternal life. God's plan, revealed by John and Paul, is a "benevolent plan, a plan of salvation": to make humanity in Christ, the Son par excellence, of whom we are the members, one body. Through Baptism, we are grafted onto Christ and are truly children of God, clothed in Him. The Holy Spirit makes us recognise God as Father, placing in our hearts the filial prayer: 'Abba, Father!'. However, the world does not yet know God because it has not opened its eyes. Only those who believe can understand the truth of divine love; for others, it seems incomprehensible or even scandalous. It is up to believers to bear witness to this love with their words and their lives, so that non-believers may, in turn, open their eyes and recognise God as Father. At the end of time, when the Son of God appears, humanity will be transformed in his image: man will rediscover the pure gaze he had lost at the beginning. Thus resounds Christ's desire to the Samaritan woman (4:1-42): "If you knew the gift of God!" An ever-present invitation to open our eyes to recognise the love that saves.

From the Gospel according to Matthew (5:1-12a)

Jesus proclaims: "Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted": it is the gift of tears. This beatitude, seemingly paradoxical, does not exalt pain but transforms it into a path of grace and hope. Jesus, who always sought to heal and console, does not invite us to take pleasure in suffering, but encourages us not to be discouraged in trials and to remain faithful in our tears, because those who suffer are already on the way to the Kingdom. The term "blessed" in the original biblical text does not indicate good fortune, but a call to persevere: it means "on the march", "take courage, keep pace, walk". Tears, then, are not an evil to be endured, but can become a place of encounter with God. There are beneficial tears, such as those of Peter's repentance, where God's mercy is experienced, or those that arise from compassion for the suffering of others, a sign that the heart of stone is becoming a heart of flesh (Ezekiel 36:26). Even tears shed in the face of the harshness of the world participate in divine compassion: they announce that the messianic time has come, when the promised consolation becomes reality. The first beatitude, 'Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven', encompasses all the others and reveals their secret. Evangelical poverty is not material poverty, but openness of heart: the poor (anawim) are those who are not self-sufficient, who are neither proud nor self-reliant, but expect everything from God. They are the humble, the little ones, those who have "bent backs" before the Lord. As in the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector, only those who recognise their own poverty can receive salvation. The poor in spirit live in total trust in God, receive everything as a gift, and pray with simplicity: "Lord, have mercy." From this inner attitude spring all the other beatitudes: mercy, meekness, peace, thirst for justice — all are fruits of the Spirit, received and not conquered. To be poor in spirit means to believe that only God fills, and that true riches are not possessions, power or knowledge, but the presence of God in a humble heart. This is why Jesus proclaims a future and paradoxical happiness: "Blessed are the poor," that is, soon you will be envied, because God will fill your emptiness with his divine riches. The beatitudes, therefore, are not moral rules but good news: they announce that God's gaze is different from that of men. Where the world sees failure — poverty, tears, persecution — God sees the raw material of his Kingdom. Jesus teaches us to look at ourselves and others with the eyes of God, to discover the presence of the Kingdom where we would never have suspected it. True happiness therefore comes from a purified gaze and from accepted weakness, which become places of grace. Those who weep, those who are poor in spirit, those who seek justice and peace, already experience the promised consolation: the joy of children who know and feel loved by the Father. As Ezekiel reminds us, on the day of judgement, those who have wept over the evil in the world will be recognised (Ezekiel 9:4): their tears are therefore already a sign of the Kingdom to come.

- +Giovanni D'Ercole

Commemoration of All Souls [2 November 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us. After contemplating the glory of Heaven, today we commemorate the destiny of light that awaits us on the day of our earthly death.

1. The commemoration of All Souls' Day was set on 2 November only at the beginning of the 11th century, linking it to the solemnity of All Saints' Day. After all, the feast of 1 November could not fail to bring to mind the faithful departed, whom the Church remembers in her prayers every day. At every Mass, we pray first of all 'for all those who rest in Christ' (Eucharistic Prayer I), then the prayer is extended to 'all the departed, whose faith you alone know' (Eucharistic Prayer IV), to 'all those who have left this life' (Eucharistic Prayer II) and 'whose righteousness you alone know' (Eucharistic Prayer III). And to make this commemoration even more participatory, today three Holy Masses can be celebrated with a wide range of readings, which I will limit myself to indicating here: A. First Mass First Reading Job 19:1, 23-27; Psalm 26/27; Second Reading St Paul to the Romans 5:5-11; From the Gospel according to John 6:37-40; B. Second Mass: First Reading Isaiah 25:6-7-9; Psalm 24/25; Second Reading Romans 8:14-23; From the Gospel according to Matthew 25:31-46); C. Third Mass: First Reading Book of Wisdom 3:1-9; Psalm 41/42 2 $2/43; Second Reading Revelation 21:1-5, 6b-7; Gospel according to Matthew 5:1-12). Given the number of biblical readings, instead of providing a commentary on each biblical passage as I do every Sunday, I prefer to offer a reflection on the meaning and value of today's celebration, which has its origins in the long history of the Catholic Church. One need only read the biblical readings to begin to doubt that the term "dead" is the most appropriate for today's Commemoration. In fact, it is in the light of Easter and in the mercy of the Lord that we are invited to meditate and pray on this day for all those who have gone before us. They have already been called to live in the light of divine life, and we too, marked with the seal of faith, will one day follow them. The Apostle Paul writes, 'We do not want you, brothers and sisters, to be ignorant about those who sleep in the Lord, so that you may not grieve as those who have no hope' (1 Thessalonians 4:13-14). Saints, when possible, are not remembered on the anniversary of their birth but are celebrated on the day of their death, which Christian tradition calls in Latin "dies natalis", meaning the day of birth into the Kingdom. For all the deceased, whether Christian, Muslim, Buddhist or of other faiths, this is their dies natalis, as we repeat in Holy Mass: "Remember all those who have left this world and whose righteousness you know; welcome them into your Kingdom, where we hope to be filled with your glory together for eternity" (Eucharistic Prayer III). The liturgy refuses to use the popular expression 'day of the dead', since this day opens onto divine life. The Church calls it: Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed. 'Dead' and 'departed' are not synonyms: the term 'departed' comes from the Latin functus, which means 'he who has accomplished', 'he who has completed'. The deceased is therefore "he who has brought to completion the life" received from God. This liturgical feast is both a day of remembrance and intercession: we remember the deceased and pray for them. In the light of the solemnity of All Saints' Day, this day offers Christians an opportunity to renew and live the hope of eternal life, the gift of Christ's resurrection. For this reason, during these celebrations, many people visit cemeteries to honour their deceased loved ones and decorate their graves with flowers. We think of all those who have left us, but whom we have not forgotten. We pray for them because, according to the Christian faith, they need purification in order to be fully with God. Our prayer can help them on this path of purification, by virtue of what is called the 'communion of saints', a communion of life that exists between us and those who have gone before us: in Christ there is a real bond and solidarity between the living and the dead.

2. A little history. In order for the feast of All Saints (established in France in 835) to retain its proper character, and so that it would not become a day dedicated to the dead, St Odilon, abbot of Cluny, around the year 1000, imposed on all his monasteries the commemoration of the dead through a solemn Mass on 2 November. This day was not called a 'day of prayer for the dead', but a 'commemoration of the dead'. At that time, the doctrine of purgatory had not yet been clearly formulated (it would only be so towards the end of the 12th century): it was mainly a matter of remembering the dead rather than praying for them. In the 15th century, the Dominicans in Spain introduced the practice of celebrating three Masses on this day. Pope Benedict XV (+1922) then extended to the whole Church the possibility of celebrating three Masses on 2 November, inviting people to pray in particular for the victims of war. On the occasion of the millennium of the institution of the Commemoration of the Faithful Departed (13 September 1998), St John Paul II wrote: "In fact, on the day after the feast of All Saints, when the Church joyfully celebrates the communion of saints and the salvation of mankind, St. Odilon wanted to exhort his monks to pray in a special way for the dead, thus contributing mysteriously to their entry into bliss. From the Abbey of Cluny, this practice gradually spread, becoming a solemn celebration in suffrage of the dead, which St Odilon called the Feast of the Dead, now universally observed throughout the Church." "In praying for the dead, the Church first of all contemplates the mystery of Christ's Resurrection, who through his Cross gives us salvation and eternal life. With St Odilon, we can repeat: 'The Cross is my refuge, the Cross is my way and my life... The Cross is my invincible weapon. It repels all evil and dispels darkness'. The Cross of the Lord reminds us that every life is inhabited by the light of Easter: no situation is lost, because Christ has conquered death and opens the way to true life for us. "Redemption is accomplished through the sacrifice of Christ, through which man is freed from sin and reconciled with God" (Tertio millennio adveniente, n. 7). "While waiting for death to be definitively conquered, some men "continue their pilgrimage on earth; others, after having ended their lives, are still being purified; and still others finally enjoy the glory of heaven and contemplate the Trinity in full light" (Lumen Gentium, n. 49). United with the merits of the saints, our fraternal prayer comes to the aid of those who are still awaiting the beatific vision. Intercession for the dead is an act of fraternal charity, proper to the one family of God, through which "we respond to the deepest vocation of the Church" (Lumen Gentium, n. 51), that is, "to save souls who will love God for eternity" (St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Prayers, 6). For the souls in purgatory, the expectation of eternal joy and the encounter with the Beloved is a source of suffering, because of the punishment due to sin that keeps them away from God; but they have the certainty that, once the time of purification is over, they will meet the One they desire (Ps 42; 62). On several occasions, various popes throughout history have urged us to pray fervently for the deceased, for our family members and for all our deceased brothers and sisters, so that they may obtain remission of the punishment due to their sins and hear the voice of the Lord calling them.

3. Why this day is important: By instituting a Mass for the commemoration of the faithful departed, the Church reminds us of the place that the deceased occupy in family and social life and recognises the painful reality of mourning: the absence of a loved one is a constant wound. This celebration can also be seen as a response to the plea of the good thief who, on the cross, turned to Jesus and said: "Remember me." In remembering our deceased, we symbolically respond to that same plea: "Remember us." It is an invitation not to forget them, to continue to pray for them, keeping their memory alive and active, a sign of our hope in eternal life. Today is therefore a day for everyone: it is not only for bereaved families, but for everyone. It helps to sensitise the faithful to the mystery of death and mourning, but also to the hope and promise of eternal life. For Christians, death is not the end, but a passage. Through the trial of mourning, we understand that our earthly life is not eternal: our deceased precede us on the path to eternity. The 2nd of November thus also becomes a lesson on the 'last things' (eschatological realities), preparing us for this passage with serenity, without fear or sadness, because it is a step towards eternal life. The Church never feels exempt from prayer: it constantly intercedes for the salvation of the world, entrusting every soul to God's mercy and judgement, so that He may grant forgiveness and the peace of the Kingdom. We know well that "fulfilling life" only makes sense in fidelity to the Lord. The Church's prayer recognises our fragility and prays that none of her children will be lost. Thus, 2 November becomes a day of faith and hope, beyond the separation that marks the end of earthly life — in peace or suffering, in solitude or in family, in martyrdom or in the goodness of loving care. Death is the hour of encounter and always remains a place of struggle. The word "agony" derives from Greek and means "struggle." For Christians, death is the encounter with the Risen One, the hope in the faith professed: I believe in the resurrection of the dead and in the life of the world to come. The believer enters death with faith, rejects despair and repeats with Jesus: 'Father, into your hands I commend my spirit' (Lk 23:46). For Christians, even the hardest death is a passage into the Risen Jesus, exalted by the Father. Very often, modern Western civilisation tends to hide death: it fears it, disguises it, distances itself from it. Even in prayer, we say distractedly: Now and at the hour of our death. Yet every year, without knowing it, we pass the date that will one day be that of our death. In the past, Christian preaching often reminded us of this, although sometimes in very emphatic tones. Today, however, the fear of death seems to want to extinguish the reality of dying, which is part of every life on earth. Today's Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed is a useful opportunity to pause and reflect and, above all, to pray, renewing our fidelity to our baptism and our vocation: Together we invoke Mary, who, raised to heaven, watches over our life and our death. Mary, icon of God's goodness and sure sign of our hope, You spent your life in love and with your own assumption into Heaven you announce to us that the Lord is not the God of the dead, but of the living. Support us on our daily journey and grant that we may live in such a way that we are ready at every moment to meet the Lord of Life in the last moment of our earthly pilgrimage when, having closed our eyes to the realities of this world, they will open to the eternal vision of God.

+ Giovanni D'Ercole