Second Sunday of Advent (year A) [7 December 2025]

May God bless us and may the Virgin protect us! From this Sunday onwards, in addition to the summary of the most important elements of each reading, I will add a brief commentary on the Gospel by a Father of the Church.

*First Reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (11:1-10)

Isaiah speaks of the root of Jesse and refers to the descendants of King David. Jesse had eight sons, but God chose Samuel not to choose the strongest or the eldest, but the youngest: David, the shepherd, who became the greatest king of Israel. From that moment on, Jesse became the progenitor of a dynasty often represented as a tree destined for a great future, which would never die. The prophet Nathan promised David that his descendants would reign forever and bring unity and peace to the people. But in history, the kings of his lineage did not fully keep these promises. However, it is precisely from disappointments that a stronger hope arises: if God has promised, then it will come to pass. How did the idea of the Messiah come about? The term 'messiah' (in Hebrew mashiach = 'anointed') originally referred to any king, because he was 'anointed' with oil on the day of his coronation. Over time, however, the word 'messiah' took on the meaning of 'ideal king', the one who brings justice, peace and happiness. When Isaiah says, 'A shoot will come up from the stump of Jesse', it means that even if David's dynasty seems like a dead tree, God can bring forth a new shoot, an ideal king: the Messiah, who will be guided by the Spirit of the Lord. The seven gifts of the Spirit, symbols of fullness, will rest upon him: wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, and the fear of the Lord, which is not fear but trust and respect as a son. The Messiah will rule as God wills: with justice and faithfulness, and his task will be to wage war on injustice: He will judge the poor with justice... not according to appearances... he will put an end to wickedness with the breath of his lips. 'The wicked' does not refer to a person, but to wickedness itself, like saying 'waging war on war'. Isaiah describes a world where the wolf lives with the lamb, the child plays without fear, there is no more violence or conflict. It is not a return to paradise on earth, but the final fulfilment of God's plan, when the knowledge of the Lord will fill the earth. The root of Jesse will be a sign for all peoples, and the Messiah concerns not only Israel but all nations. Jesus himself will take up this idea: "When I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all people to myself" (Jn 12:32). Isaiah preaches in the eighth century BC, at a time of political pressure and threats from neighbouring empires. The tree of David seems to be dead, but Isaiah urges us not to lose hope. The "animal fable" uses symbols to speak of human beings, as La Fontaine would do many centuries later, and constitutes a promise of peace, brotherhood and universal reconciliation. Martin Luther King, in his "I have a dream" speech, drew direct inspiration from these images used by Isaiah (cf. 11:2): a world where justice and brotherhood overcome violence.

The central theme can be summed up in one sentence: From the seemingly dead trunk of David's dynasty, God is so faithful that, when all seems lost, he revives his promise from a fragment, from a stump: hope is born precisely where man can no longer see anything. God will raise up a Messiah guided by the Spirit, who will fight injustice and bring universal peace to all peoples. God is faithful, and even from a dead trunk he can bring forth new life. It is messianic peace, the final reconciliation of creation. There are times when we too feel like a cut tree: failures, disappointments, repeated sins, broken relationships, projects that do not come to fruition, communities that seem to be losing strength. Isaiah announces: God is not finished with you either, and even where you see no future, He sees a sprout. Continue to hope, because God sees sprouts where we see only dry wood.

*Responsorial Psalm (71/72, 1-2, 7-8, 12-13, 17)

Psalm 71/72 is a prayer that arose after the Babylonian exile, at a time when there was no longer a king in Israel. This means that the psalm no longer speaks of an earthly ruler, but of the king promised by God: the Messiah. Since it is God who promises him, his fulfilment is certain. The entire Bible is permeated with an indestructible hope: history has meaning and direction, and God has a plan of happiness for humanity. This plan takes on different names (the Day of the Lord, the Kingdom of Heaven, the benevolent plan), but it is always the same: like a lover who repeats words of love, God tirelessly proposes his plan of salvation.

This plan is announced from the beginning, in the vocation of Abraham (Gen 12:3): 'All the families of the earth shall be blessed in you'. The revelation is therefore universal from the outset. Israel is chosen not to manage a privilege, but to be a service and a sign for all peoples. The psalm takes up this promise: in the Messiah, all nations will be blessed and will call him blessed. It also takes up the other promise made to Abraham (Gen 15:18), namely the gift of the land "from the river of Egypt to the great river". Echoing this, the psalm says: "He shall rule from sea to sea and from the River to the ends of the earth." The book of Sirach (Sir 44:21) confirms this reading, linking together universal blessing, multiplication of descendants and extended inheritance. Although today the idea of a universal ruler may seem far removed from democratic sensibilities, and indeed there is fear of the imposition of a hidden world authority that would dominate the whole of humanity, the Bible reminds us that every ruler is only an instrument in the hands of God, and what matters is the people, considering the whole of humanity as one vast people, and the psalm announces a pacified humanity: In those days, justice will flourish, great peace until the end of time, poverty and oppression defeated. The dream of justice and peace runs through the entire Scripture: Jerusalem means 'city of peace'; Deuteronomy 15 states that there will be no more poor people. The psalm fits into this line: the Messiah will help the poor who cry out, the weak without help, the miserable who have no defence. The prayer of the psalm does not serve to remind God of his promises, because God does not forget. Instead, it serves to help man learn to look at the world through God's eyes, remember his plan and find the strength to work towards its realisation. Justice, peace and the liberation of the poor will not come about magically: God invites believers to cooperate, allowing themselves to be guided by the Holy Spirit with light, strength and grace.

Important points to remember: +Psalm 72 is messianic: written when there were no more kings, it announces the Messiah promised by God.+History has meaning: God has a plan of happiness for all humanity.+The promises to Abraham are the foundation: universal blessing and inheritance without borders.+The Messiah will be God's instrument, serving the people and not power.+The world to come will be marked by justice, peace and an end to poverty. +Prayer is not meant to convince God, but to educate us: it opens our eyes to God's plan. Peace and justice will also come through human commitment guided by the Spirit.

Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul to the Romans (15:4-9)

Saint Paul writes to the Romans: 'Everything that was written before us was written for our instruction... so that we may keep hope alive'. This sentence is the key to reading the entire Bible: Scripture exists to enlighten, liberate and give hope. If a text seems obscure or difficult, it simply means that we have not yet fully understood it: the Good News is always present and we must dig to find it, as if it were a hidden treasure. Scripture nourishes hope because it proclaims on every page a single plan of God: that "merciful design" which is the great love story of God with humanity. The entire Bible, from the Old to the New Testament, has only one subject: the plan of salvation and communion that God wants to realise in the Messiah. Paul then moves on to a concrete theme: the Christians in Rome were divided. There were two groups: Christians who came from Judaism and were still attached to Jewish religious and dietary practices, and Christians who came from paganism and considered such observances outdated. This diversity gave rise to discord, mutual judgement and suspicion. Liturgical and cultural differences became real conflicts. This situation is very similar to the tensions that exist even today in the Church between different sensibilities. Paul does not propose dividing the community into two separate groups. Instead, he proposes the path of cohabitation, the building of peace, patience and mutual tolerance, inviting everyone to seek what promotes peace and what builds up the community. Let each one seek the good of the other, and may 'the God of perseverance and consolation' grant you to live in harmony according to Christ. The fundamental principle is: 'Welcome one another as Christ has welcomed you'. Paul recalls that Christ took upon himself the mission of the Servant of God announced by Isaiah: chosen and elected by God, formed every morning by the Word, giver of his own life, bringer of salvation to all nations. Christ, by dying and rising again, united the Jews, saved in continuity with their Covenant, and the pagans, saved by God's gratuitous mercy. For this reason, no one can claim superiority; rather, everything is grace, everything is a gift from Christ, and true worship is this: to overcome the past, to recognise the gift received, to welcome one another without distinction, to sing together of God's faithfulness and mercy.

Important elements to remember: +Scripture exists to give hope. Every page of the Bible is Good News. If we do not find liberation, we have not yet understood the text. + The Bible proclaims a single plan. God's "providential plan" is to bring humanity to communion and salvation through the Messiah. +Paul corrects a divided community: In Rome, there were tensions between Christians of Jewish and pagan origin. Practical and cultural differences created judgements and conflicts. The Christian solution is not to separate. Paul proposes cohabitation, patience, and mutual edification. The community is a 'building' that must be constructed with peace and tolerance. +The model is Christ the Servant who united everyone: Jews and pagans. No one can boast: everything is grace. +The watchword: welcome: Welcome one another as Christ has welcomed you. The Church is alive when it overcomes divisions and lives mercy.

*From the Gospel according to Matthew (3:1-12)

When John the Baptist begins his preaching, Judea has been under Roman rule for 90 years, Herod is in power but deeply hated; religious currents are divided and confused; there are collaborators, resisters, false prophets, messianic agitators. The people are tired and disoriented, and it is in this climate that the preaching of John, who lives in the desert of Judea (between Jerusalem and the Jordan), begins. Matthew insists on the spiritual meaning of the desert: he recalls the Exodus, the Covenant, purification, the loving relationship between God and Israel (Hosea) and sees the desert as the place of return to truth and decision. In John, everything recalls the great prophets: he wears camel's hair, eats locusts and honey, and lives an ascetic lifestyle. Many consider him the possible return of Elijah, awaited to prepare for the coming of God (Malachi 3:23). His preaching has a double prophetic tone: sweet and comforting for the humble; harsh and provocative for the proud. The expression "brood of vipers" is not a personal insult, but a way of saying, "you are following the logic of the tempting serpent," and is therefore an invitation to change one's attitude. John invites everyone to make a righteous discernment in their lives: what is healthy remains, what is corrupt is eliminated. And to be incisive, he uses strong images: fire burning straw (a reference to the prophet Malachi), a sieve separating wheat from chaff, a threshing floor where the choice is made - and this is the meaning: everything in us that is death will be purified; everything that is authentic will be saved and preserved. It is a liberating judgement, not a destructive one. John announces Jesus: 'I baptise you with water, but the one who comes after me... will baptise you with the Holy Spirit and fire'. Only God can give the Spirit, and so John implicitly affirms the divinity of Jesus. The images used: 'Stronger than me' is a typical attribute of God. "I am not worthy to carry his sandals or untie his sandals": with this he recognises Jesus' divine dignity. Although he is a teacher followed by disciples, John puts himself in the second row; he recognises Jesus' superiority and paves the way for the Messiah. His greatness consists precisely in making room. Matthew shows him as a "voice in the desert" with reference to Isaiah 40:3, also linked to Elijah (2 Kings 1:8; Malachi 3:23), in the line of prophets to introduce Jesus as God present and judge. Chapters 3-4 of Matthew are a hinge: here begins the preaching of the Kingdom.

Important elements to remember: +John appears in a context of oppression and moral confusion: his word brings light and discernment. +The desert is a place of new covenant, truth and conversion. +John presents himself with prophetic signs (clothing, food, style) reminiscent of Elijah. +His preaching is twofold: consolation for the little ones, provocation for those who are sure of themselves. +Judgement is internal, not against categories of people: it purifies the evil in each person. Fire does not destroy man, but what is dead in him: it is a fire of love and truth. +Jesus accomplishes purification by baptising in the Holy Spirit, something that only God can do, and John recognises the divinity of Jesus with gestures of great humility. +The greatness of the Precursor lies in stepping aside to make room for the Messiah, and Matthew places him as a bridge between the Old and New Covenants, inaugurating the preaching of the Kingdom.

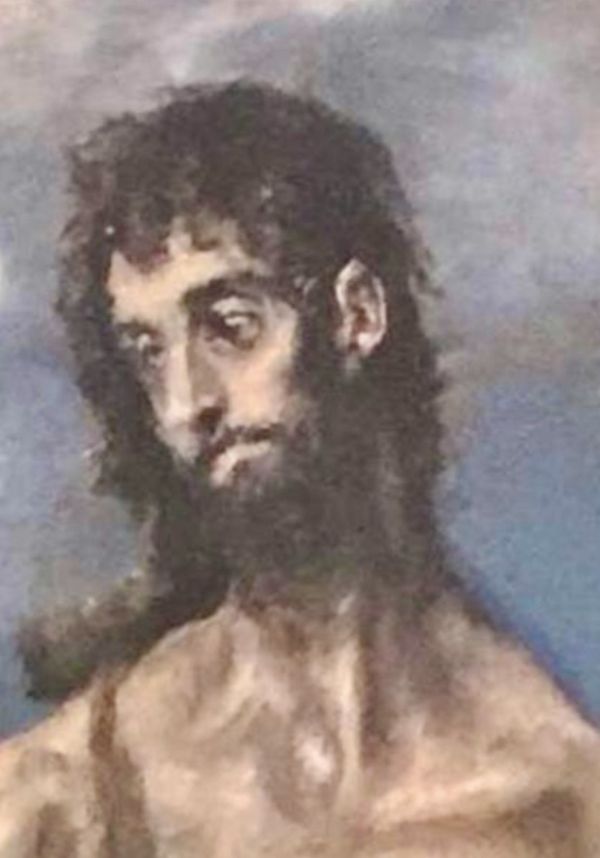

St John Chrysostom – Commentary on Matthew 3:1-12

'John appears in the desert not by chance, but to recall the ancient path of Israel.

Israel was educated in the desert, and now conversion begins again in the desert. His rough clothing and simple food show that he is free from all vanity, like Elijah. For this reason, the people, tired of the leaders of the time, flock to him: they see in John a truthful man who does not seek glory but leads to the truth." Chrysostom then explains the prophetic and moral content of John's preaching: By calling them a 'brood of vipers', he is not insulting them, but shaking them up so that they realise the poison that corrupts them. He does not attack people, but the evil that possesses them.

The judgement he announces is not against men, but against their evil deeds: fire burns guilt, not human nature." And regarding the announcement of the Messiah: "By saying, 'One more powerful than I is coming after me,' John does not compare himself to another man, but to God. For only God is said to be the Strong One. And when he adds, 'He will baptise you with the Holy Spirit', he openly confesses that the One who is coming has divine power. For this reason, he declares that he is not even worthy to untie his sandals: not because he despises himself, but because he recognises the greatness of Christ." Finally, Chrysostom interprets the mission of the Precursor:

"His greatness consists in diminishing so that Christ may grow. He is the voice that prepares the Word; he is the bridge that connects the Old Covenant to the New. He shows that all that the prophets awaited is now fulfilled: the King is near, and the Kingdom begins."

+Giovanni D'Ercole