Whole-heartedly. I emphasise, here, the adjective 'whole'. Totalitarianism in politics is bad. In religion, on the other hand, our totalitarianism in the face of God is perfectly fine. It is written: "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength. These precepts which I give thee today, let them be fixed in thy heart; thou shalt repeat them to thy children, thou shalt speak of them when thou sittest in thy house, when thou walkest by the way, when thou liest down, and when thou risest up. You shall bind them to your hand as a sign, they shall be like a pendant between your eyes, and you shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your doors". That "all" repeated and bent into practice with such insistence is truly the banner of Christian maximalism. And it is right: God is too great, too much He deserves from us, for us to throw to Him, as to a poor Lazarus, just a few crumbs of our time and heart. He is infinite good and will be our eternal happiness: the money, the pleasures, the fortunes of this world, in comparison with Him, are barely fragments of good and fleeting moments of happiness. It would be unwise to give so much of us to these things and so little of us to Jesus. Above all things. Now we come to a direct comparison between God and man, between God and the world. It would not be right to say: "Either God or man". One must love "and God and man"; the latter, however, never more than God or against God or equal to God. In other words: God's love is indeed prevalent, but not exclusive. The Bible declares Jacob holy and beloved of God, shows him working seven years to win Rachel as his wife; "and they seemed to him but a few days, those years, so great was his love for her". Francis de Sales comments on these words: "Jacob," he writes, "loves Rachel with all his strength, and with all his strength he loves God; but he does not love Rachel as God nor God as Rachel. He loves God as his God above all things and more than himself; he loves Rachel as his wife above all other women and as himself. He loves God with absolutely and sovereignly supreme love, and Rachel with supreme marital love; the one love is not contrary to the other, because Rachel's love does not violate the supreme advantages of the love of God". And for your sake I love my neighbour. Here we are faced with two loves that are "twin brothers" and inseparable. Some people it is easy to love; others, it is difficult; we do not like them, they have offended us and done us harm; only if I love God seriously, do I come to love them, as daughters of God and because he asks me to. Jesus also laid down how to love one's neighbour: not only with feeling, but with deeds. This is the way, he said. I will ask you: I was hungry in the person of my least brothers, did you give me food? Did you visit me when I was sick?

The Catechism translates these and other words from the Bible into the double list of the seven corporal and seven spiritual works of mercy. The list is not complete and should be updated. Among the hungry, for example, today, it is no longer just about this or that individual; there are whole peoples.

We all remember the great words of Pope Paul VI: 'The peoples of hunger today dramatically challenge the peoples of affluence. The Church trembles before this cry of anguish and calls each one to respond with love to his brother'. At this point charity is joined by justice, because - Paul VI goes on to say - "private property does not constitute for anyone an unconditional and absolute right. No one is authorised to reserve for his own exclusive use what exceeds his need, when others lack the necessary". Consequently, 'every exhausting arms race becomes an intolerable scandal'.

In the light of these strong expressions, we see how far we - individuals and peoples - are still from loving others 'as ourselves', which is Jesus' command.

Another command: forgive offences received. It seems as if the Lord gives this forgiveness precedence over worship: "If therefore you present your offering on the altar and there you remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go first to be reconciled with your brother and then return to offer your gift".

The last words of the prayer are: Lord, may I love you more and more. Here too there is obedience to a command from God, who has put the thirst for progress in our hearts. From stilts, caves and the first huts, we have moved on to houses, palaces, skyscrapers; from travelling on foot, on the back of a mule or camel, to carriages, trains, planes. And we still want to progress by ever faster means, reaching ever more distant destinations. But loving God - we have seen it - is also a journey: God wants it more and more intense and perfect. He said to all his own: 'You are the light of the world, the salt of the earth'; 'be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect'. This means: love God not a little, but a lot; do not stop at the point where you have arrived, but with His help, progress in love.

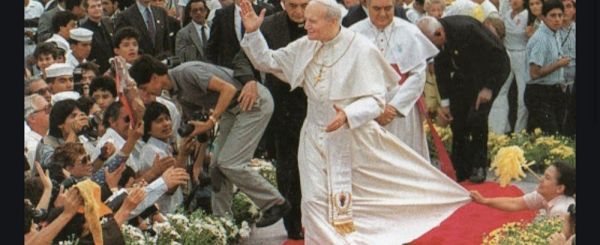

[Pope John Paul II, General Audience 27 September 1978]